- [ May 9, 2024 ] Moon Phases: What They Are & How They Work Solar System

- [ April 3, 2024 ] Giordano Bruno Quotes About Astronomy Astronomy Lists

- [ March 28, 2024 ] Shakespeare Quotes: Comets, Meteors and Shooting Stars Astronomy Lists

- [ March 28, 2024 ] Shakespearean Quotes About The Moon Astronomy Lists

- [ November 30, 2022 ] The Night Sky This Month: December 2022 Night Sky

5 Bizarre Paradoxes Of Time Travel Explained

December 20, 2014 James Miller Astronomy Lists , Time Travel 58

There is nothing in Einstein’s theories of relativity to rule out time travel , although the very notion of traveling to the past violates one of the most fundamental premises of physics, that of causality. With the laws of cause and effect out the window, there naturally arises a number of inconsistencies associated with time travel, and listed here are some of those paradoxes which have given both scientists and time travel movie buffs alike more than a few sleepless nights over the years.

Types of Temporal Paradoxes

The time travel paradoxes that follow fall into two broad categories:

1) Closed Causal Loops , such as the Predestination Paradox and the Bootstrap Paradox, which involve a self-existing time loop in which cause and effect run in a repeating circle, but is also internally consistent with the timeline’s history.

2) Consistency Paradoxes , such as the Grandfather Paradox and other similar variants such as The Hitler paradox, and Polchinski’s Paradox, which generate a number of timeline inconsistencies related to the possibility of altering the past.

1: Predestination Paradox

A Predestination Paradox occurs when the actions of a person traveling back in time become part of past events, and may ultimately cause the event he is trying to prevent to take place. The result is a ‘temporal causality loop’ in which Event 1 in the past influences Event 2 in the future (time travel to the past) which then causes Event 1 to occur.

This circular loop of events ensures that history is not altered by the time traveler, and that any attempts to stop something from happening in the past will simply lead to the cause itself, instead of stopping it. Predestination paradoxes suggest that things are always destined to turn out the same way and that whatever has happened must happen.

Sound complicated? Imagine that your lover dies in a hit-and-run car accident, and you travel back in time to save her from her fate, only to find that on your way to the accident you are the one who accidentally runs her over. Your attempt to change the past has therefore resulted in a predestination paradox. One way of dealing with this type of paradox is to assume that the version of events you have experienced are already built into a self-consistent version of reality, and that by trying to alter the past you will only end up fulfilling your role in creating an event in history, not altering it.

– Cinema Treatment

In The Time Machine (2002) movie, for instance, Dr. Alexander Hartdegen witnesses his fiancee being killed by a mugger, leading him to build a time machine to travel back in time to save her from her fate. His subsequent attempts to save her fail, though, leading him to conclude that “I could come back a thousand times… and see her die a thousand ways.” After then traveling centuries into the future to see if a solution has been found to the temporal problem, Hartdegen is told by the Über-Morlock:

“You built your time machine because of Emma’s death. If she had lived, it would never have existed, so how could you use your machine to go back and save her? You are the inescapable result of your tragedy, just as I am the inescapable result of you .”

- Movies : Examples of predestination paradoxes in the movies include 12 Monkeys (1995), TimeCrimes (2007), The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009), and Predestination (2014).

- Books : An example of a predestination paradox in a book is Phoebe Fortune and the Pre-destination Paradox by M.S. Crook.

2: Bootstrap Paradox

A Bootstrap Paradox is a type of paradox in which an object, person, or piece of information sent back in time results in an infinite loop where the object has no discernible origin, and exists without ever being created. It is also known as an Ontological Paradox, as ontology is a branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of being or existence.

– Information : George Lucas traveling back in time and giving himself the scripts for the Star War movies which he then goes on to direct and gain great fame for would create a bootstrap paradox involving information, as the scripts have no true point of creation or origin.

– Person : A bootstrap paradox involving a person could be, say, a 20-year-old male time traveler who goes back 21 years, meets a woman, has an affair, and returns home three months later without knowing the woman was pregnant. Her child grows up to be the 20-year-old time traveler, who travels back 21 years through time, meets a woman, and so on. American science fiction writer Robert Heinlein wrote a strange short story involving a sexual paradox in his 1959 classic “All You Zombies.”

These ontological paradoxes imply that the future, present, and past are not defined, thus giving scientists an obvious problem on how to then pinpoint the “origin” of anything, a word customarily referring to the past, but now rendered meaningless. Further questions arise as to how the object/data was created, and by whom. Nevertheless, Einstein’s field equations allow for the possibility of closed time loops, with Kip Thorne the first theoretical physicist to recognize traversable wormholes and backward time travel as being theoretically possible under certain conditions.

- Movies : Examples of bootstrap paradoxes in the movies include Somewhere in Time (1980), Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989), the Terminator movies, and Time Lapse (2014). The Netflix series Dark (2017-19) also features a book called ‘A Journey Through Time’ which presents another classic example of a bootstrap paradox.

- Books : Examples of bootstrap paradoxes in books include Michael Moorcock’s ‘Behold The Man’, Tim Powers’ The Anubis Gates, and Heinlein’s “By His Bootstraps”

3: Grandfather Paradox

The Grandfather Paradox concerns ‘self-inconsistent solutions’ to a timeline’s history caused by traveling back in time. For example, if you traveled to the past and killed your grandfather, you would never have been born and would not have been able to travel to the past – a paradox.

Let’s say you did decide to kill your grandfather because he created a dynasty that ruined the world. You figure if you knock him off before he meets your grandmother then the whole family line (including you) will vanish and the world will be a better place. According to theoretical physicists, the situation could play out as follows:

– Timeline protection hypothesis: You pop back in time, walk up to him, and point a revolver at his head. You pull the trigger but the gun fails to fire. Click! Click! Click! The bullets in the chamber have dents in the firing caps. You point the gun elsewhere and pull the trigger. Bang! Point it at your grandfather.. Click! Click! Click! So you try another method to kill him, but that only leads to scars that in later life he attributed to the world’s worst mugger. You can do many things as long as they’re not fatal until you are chased off by a policeman.

– Multiple universes hypothesis: You pop back in time, walk up to him, and point a revolver at his head. You pull the trigger and Boom! The deed is done. You return to the “present,” but you never existed here. Everything about you has been erased, including your family, friends, home, possessions, bank account, and history. You’ve entered a timeline where you never existed. Scientists entertain the possibility that you have now created an alternate timeline or entered a parallel universe.

- Movies : Example of the Grandfather Paradox in movies include Back to the Future (1985), Back to the Future Part II (1989), and Back to the Future Part III (1990).

- Books : Example of the Grandfather Paradox in books include Dr. Quantum in the Grandfather Paradox by Fred Alan Wolf , The Grandfather Paradox by Steven Burgauer, and Future Times Three (1944) by René Barjavel, the very first treatment of a grandfather paradox in a novel.

4: Let’s Kill Hitler Paradox

Similar to the Grandfather Paradox which paradoxically prevents your own birth, the Killing Hitler paradox erases your own reason for going back in time to kill him. Furthermore, while killing Grandpa might have a limited “butterfly effect,” killing Hitler would have far-reaching consequences for everyone in the world, even if only for the fact you studied him in school.

The paradox itself arises from the idea that if you were successful, then there would be no reason to time travel in the first place. If you killed Hitler then none of his actions would trickle down through history and cause you to want to make the attempt.

- Movies/Shows : By far the best treatment for this notion occurred in a Twilight Zone episode called Cradle of Darkness which sums up the difficulties involved in trying to change history, with another being an episode of Dr Who called ‘Let’s Kill Hitler’.

- Books : Examples of the Let’s Kill Hitler Paradox in books include How to Kill Hitler: A Guide For Time Travelers by Andrew Stanek, and the graphic novel I Killed Adolf Hitler by Jason.

5: Polchinski’s Paradox

American theoretical physicist Joseph Polchinski proposed a time paradox scenario in which a billiard ball enters a wormhole, and emerges out the other end in the past just in time to collide with its younger version and stop it from going into the wormhole in the first place.

Polchinski’s paradox is taken seriously by physicists, as there is nothing in Einstein’s General Relativity to rule out the possibility of time travel, closed time-like curves (CTCs), or tunnels through space-time. Furthermore, it has the advantage of being based upon the laws of motion, without having to refer to the indeterministic concept of free will, and so presents a better research method for scientists to think about the paradox. When Joseph Polchinski proposed the paradox, he had Novikov’s Self-Consistency Principle in mind, which basically states that while time travel is possible, time paradoxes are forbidden.

However, a number of solutions have been formulated to avoid the inconsistencies Polchinski suggested, which essentially involves the billiard ball delivering a blow that changes its younger version’s course, but not enough to stop it from entering the wormhole. This solution is related to the ‘timeline-protection hypothesis’ which states that a probability distortion would occur in order to prevent a paradox from happening. This also helps explain why if you tried to time travel and murder your grandfather, something will always happen to make that impossible, thus preserving a consistent version of history.

- Books: Paradoxes of Time Travel by Ryan Wasserman is a wide-ranging exploration of time and time travel, including Polchinski’s Paradox.

Are Self-Fulfilling Prophecies Paradoxes?

A self-fulfilling prophecy is only a causality loop when the prophecy is truly known to happen and events in the future cause effects in the past, otherwise the phenomenon is not so much a paradox as a case of cause and effect. Say, for instance, an authority figure states that something is inevitable, proper, and true, convincing everyone through persuasive style. People, completely convinced through rhetoric, begin to behave as if the prediction were already true, and consequently bring it about through their actions. This might be seen best by an example where someone convincingly states:

“High-speed Magnetic Levitation Trains will dominate as the best form of transportation from the 21st Century onward.”

Jet travel, relying on diminishing fuel supplies, will be reserved for ocean crossing, and local flights will be a thing of the past. People now start planning on building networks of high-speed trains that run on electricity. Infrastructure gears up to supply the needed parts and the prediction becomes true not because it was truly inevitable (though it is a smart idea), but because people behaved as if it were true.

It even works on a smaller scale – the scale of individuals. The basic methodology for all those “self-help” books out in the world is that if you modify your thinking that you are successful (money, career, dating, etc.), then with the strengthening of that belief you start to behave like a successful person. People begin to notice and start to treat you like a successful person; it is a reinforcement/feedback loop and you actually become successful by behaving as if you were.

Are Time Paradoxes Inevitable?

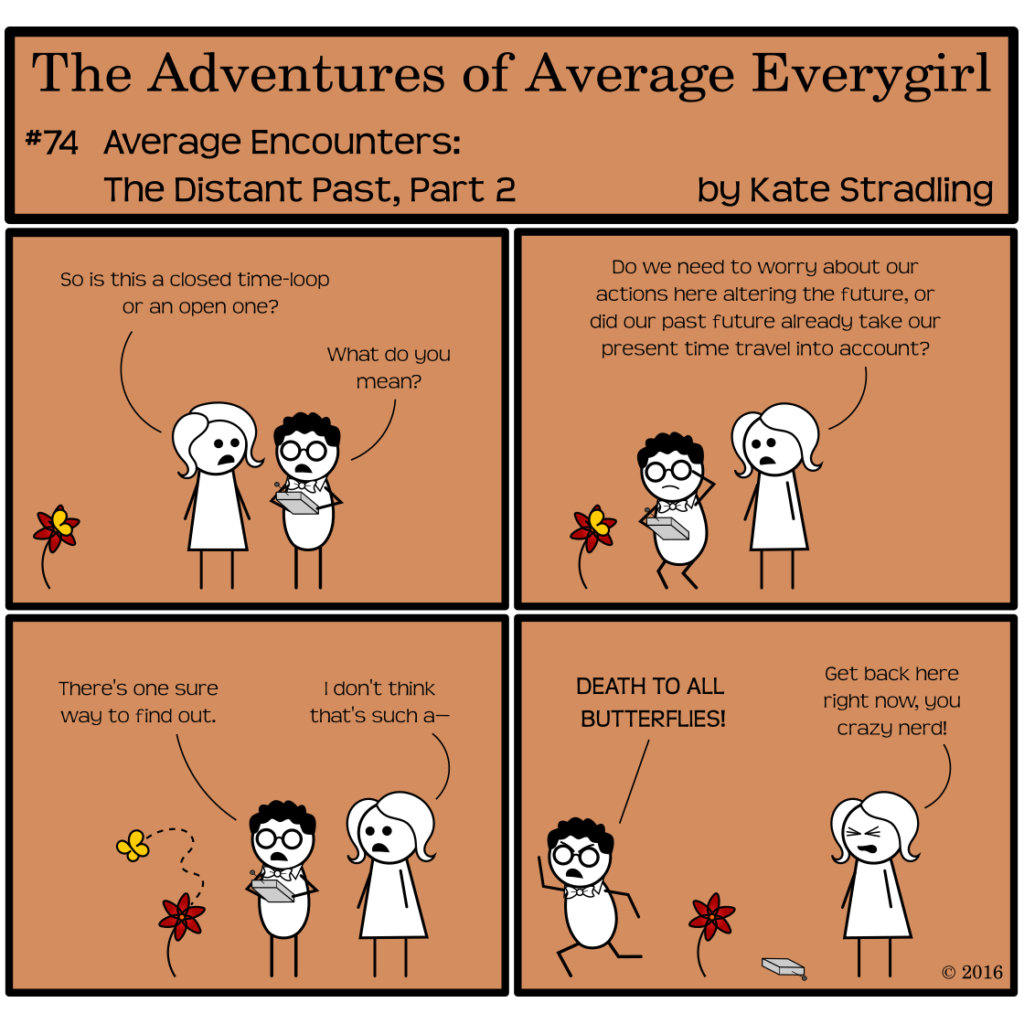

The Butterfly Effect is a reference to Chaos Theory where seemingly trivial changes can have huge cascade reactions over long periods of time. Consequently, the Timeline corruption hypothesis states that time paradoxes are an unavoidable consequence of time travel, and even insignificant changes may be enough to alter history completely.

In one story, a paleontologist, with the help of a time travel device, travels back to the Jurassic Period to get photographs of Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Allosaurus amongst other dinosaurs. He knows he can’t take samples so he just takes magnificent pictures from the fixed platform that is positioned precisely to not change anything about the environment. His assistant is about to pick a long blade of grass, but he stops him and explains how nothing must change because of their presence. They finish what they are doing and return to the present, but everything is gone. They reappear in a wild world with no humans and no signs that they ever existed. They fall to the floor of their platform, the only man-made thing in the whole world, and lament “Why? We didn’t change anything!” And there on the heel of the scientist’s shoe is a crushed butterfly.

The Butterfly Effect is also a movie, starring Ashton Kutcher as Evan Treborn and Amy Smart as Kayleigh Miller, where a troubled man has had blackouts during his youth, later explained by him traveling back into his own past and taking charge of his younger body briefly. The movie explores the issue of changing the timeline and how unintended consequences can propagate.

Scientists eager to avoid the paradoxes presented by time travel have come up with a number of ingenious ways in which to present a more consistent version of reality, some of which have been touched upon here, including:

- The Solution: time travel is impossible because of the very paradox it creates.

- Self-healing hypothesis: successfully altering events in the past will set off another set of events which will cause the present to remain the same.

- The Multiverse or “many-worlds” hypothesis: an alternate parallel universe or timeline is created each time an event is altered in the past.

- Erased timeline hypothesis : a person traveling to the past would exist in the new timeline, but have their own timeline erased.

Related Posts

© Copyright 2023 Astronomy Trek

Advertisement

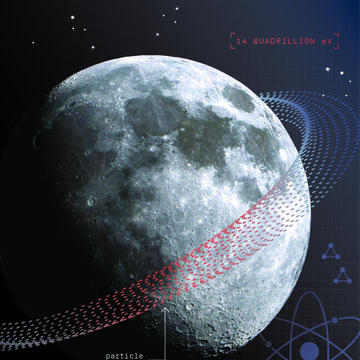

Time loops may not be forbidden by physics after all

Physicists find that causal loops, where two events separated in time influence each other in paradoxical ways, are allowed in many theoretical universes, some of which share features with our own

By Karmela Padavic-Callaghan

5 July 2022

In certain universes, achieving a time loop is possible without breaking physics

andrey_l/Shutterstock

A causal loop is a classic time travel conundrum. If you send information to the past – say, you give Albert Einstein the formula E=mc ² before he theorises it himself, then he publishes it and you go on to find it in a textbook – you would create a situation in which the information has no true origin.

A new analysis shows that this type of causal loop is possible in more theoretical universes than had previously been expected.

In most science-fiction scenarios, sending messages back in…

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

To continue reading, subscribe today with our introductory offers

No commitment, cancel anytime*

Offer ends 2nd of July 2024.

*Cancel anytime within 14 days of payment to receive a refund on unserved issues.

Inclusive of applicable taxes (VAT)

Existing subscribers

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

How physics is helping us to explain why time always moves forwards

Subscriber-only

How materials that rewind light can test physics' most extreme ideas

Time may be an illusion created by quantum entanglement

Quantum time travel: The experiment to 'send a particle into the past'

Popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

September 2, 2014

Time Travel Simulation Resolves “Grandfather Paradox”

What would happen to you if you went back in time and killed your grandfather? A model using photons reveals that quantum mechanics can solve the quandary—and even foil quantum cryptography

By Lee Billings

On June 28, 2009, the world-famous physicist Stephen Hawking threw a party at the University of Cambridge, complete with balloons, hors d'oeuvres and iced champagne. Everyone was invited but no one showed up. Hawking had expected as much, because he only sent out invitations after his party had concluded. It was, he said, "a welcome reception for future time travelers," a tongue-in-cheek experiment to reinforce his 1992 conjecture that travel into the past is effectively impossible.

But Hawking may be on the wrong side of history. Recent experiments offer tentative support for time travel's feasibility—at least from a mathematical perspective. The study cuts to the core of our understanding of the universe, and the resolution of the possibility of time travel, far from being a topic worthy only of science fiction, would have profound implications for fundamental physics as well as for practical applications such as quantum cryptography and computing.

Closed timelike curves The source of time travel speculation lies in the fact that our best physical theories seem to contain no prohibitions on traveling backward through time. The feat should be possible based on Einstein's theory of general relativity, which describes gravity as the warping of spacetime by energy and matter. An extremely powerful gravitational field, such as that produced by a spinning black hole, could in principle profoundly warp the fabric of existence so that spacetime bends back on itself. This would create a "closed timelike curve," or CTC, a loop that could be traversed to travel back in time.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hawking and many other physicists find CTCs abhorrent, because any macroscopic object traveling through one would inevitably create paradoxes where cause and effect break down. In a model proposed by the theorist David Deutsch in 1991, however, the paradoxes created by CTCs could be avoided at the quantum scale because of the behavior of fundamental particles, which follow only the fuzzy rules of probability rather than strict determinism. "It's intriguing that you've got general relativity predicting these paradoxes, but then you consider them in quantum mechanical terms and the paradoxes go away," says University of Queensland physicist Tim Ralph. "It makes you wonder whether this is important in terms of formulating a theory that unifies general relativity with quantum mechanics."

Experimenting with a curve Recently Ralph and his PhD student Martin Ringbauer led a team that experimentally simulated Deutsch's model of CTCs for the very first time, testing and confirming many aspects of the two-decades-old theory. Their findings are published in Nature Communications. Much of their simulation revolved around investigating how Deutsch's model deals with the “grandfather paradox,” a hypothetical scenario in which someone uses a CTC to travel back through time to murder her own grandfather, thus preventing her own later birth. ( Scientific American is part of Nature Publishing Group.)

Deutsch's quantum solution to the grandfather paradox works something like this:

Instead of a human being traversing a CTC to kill her ancestor, imagine that a fundamental particle goes back in time to flip a switch on the particle-generating machine that created it. If the particle flips the switch, the machine emits a particle— the particle—back into the CTC; if the switch isn't flipped, the machine emits nothing. In this scenario there is no a priori deterministic certainty to the particle's emission, only a distribution of probabilities. Deutsch's insight was to postulate self-consistency in the quantum realm, to insist that any particle entering one end of a CTC must emerge at the other end with identical properties. Therefore, a particle emitted by the machine with a probability of one half would enter the CTC and come out the other end to flip the switch with a probability of one half, imbuing itself at birth with a probability of one half of going back to flip the switch. If the particle were a person, she would be born with a one-half probability of killing her grandfather, giving her grandfather a one-half probability of escaping death at her hands—good enough in probabilistic terms to close the causative loop and escape the paradox. Strange though it may be, this solution is in keeping with the known laws of quantum mechanics.

In their new simulation Ralph, Ringbauer and their colleagues studied Deutsch's model using interactions between pairs of polarized photons within a quantum system that they argue is mathematically equivalent to a single photon traversing a CTC. "We encode their polarization so that the second one acts as kind of a past incarnation of the first,” Ringbauer says. So instead of sending a person through a time loop, they created a stunt double of the person and ran him through a time-loop simulator to see if the doppelganger emerging from a CTC exactly resembled the original person as he was in that moment in the past.

By measuring the polarization states of the second photon after its interaction with the first, across multiple trials the team successfully demonstrated Deutsch's self-consistency in action. "The state we got at our output, the second photon at the simulated exit of the CTC, was the same as that of our input, the first encoded photon at the CTC entrance," Ralph says. "Of course, we're not really sending anything back in time but [the simulation] allows us to study weird evolutions normally not allowed in quantum mechanics."

Those "weird evolutions" enabled by a CTC, Ringbauer notes, would have remarkable practical applications, such as breaking quantum-based cryptography through the cloning of the quantum states of fundamental particles. "If you can clone quantum states,” he says, “you can violate the Heisenberg uncertainty principle,” which comes in handy in quantum cryptography because the principle forbids simultaneously accurate measurements of certain kinds of paired variables, such as position and momentum. "But if you clone that system, you can measure one quantity in the first and the other quantity in the second, allowing you to decrypt an encoded message."

"In the presence of CTCs, quantum mechanics allows one to perform very powerful information-processing tasks, much more than we believe classical or even normal quantum computers could do," says Todd Brun, a physicist at the University of Southern California who was not involved with the team's experiment. "If the Deutsch model is correct, then this experiment faithfully simulates what could be done with an actual CTC. But this experiment cannot test the Deutsch model itself; that could only be done with access to an actual CTC."

Alternative reasoning Deutsch's model isn’t the only one around, however. In 2009 Seth Lloyd, a theorist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, proposed an alternative , less radical model of CTCs that resolves the grandfather paradox using quantum teleportation and a technique called post-selection, rather than Deutsch's quantum self-consistency. With Canadian collaborators, Lloyd went on to perform successful laboratory simulations of his model in 2011. "Deutsch's theory has a weird effect of destroying correlations," Lloyd says. "That is, a time traveler who emerges from a Deutschian CTC enters a universe that has nothing to do with the one she exited in the future. By contrast, post-selected CTCs preserve correlations, so that the time traveler returns to the same universe that she remembers in the past."

This property of Lloyd's model would make CTCs much less powerful for information processing, although still far superior to what computers could achieve in typical regions of spacetime. "The classes of problems our CTCs could help solve are roughly equivalent to finding needles in haystacks," Lloyd says. "But a computer in a Deutschian CTC could solve why haystacks exist in the first place.”

Lloyd, though, readily admits the speculative nature of CTCs. “I have no idea which model is really right. Probably both of them are wrong,” he says. Of course, he adds, the other possibility is that Hawking is correct, “that CTCs simply don't and cannot exist." Time-travel party planners should save the champagne for themselves—their hoped-for future guests seem unlikely to arrive.

The Quantum Physics of Time Travel (All-Access Subscribers Only) By David Deutsch and Michael Lockwood

Can Quantum Bayesianism Fix the Paradoxes of Quantum Mechanics?

Astrophysicist J. Richard Gott on Time Travel

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Time Travel

There is an extensive literature on time travel in both philosophy and physics. Part of the great interest of the topic stems from the fact that reasons have been given both for thinking that time travel is physically possible—and for thinking that it is logically impossible! This entry deals primarily with philosophical issues; issues related to the physics of time travel are covered in the separate entries on time travel and modern physics and time machines . We begin with the definitional question: what is time travel? We then turn to the major objection to the possibility of backwards time travel: the Grandfather paradox. Next, issues concerning causation are discussed—and then, issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We end with a discussion of the question why, if backwards time travel will ever occur, we have not been visited by time travellers from the future.

1.1 Time Discrepancy

1.2 changing the past, 2.1 can and cannot, 2.2 improbable coincidences, 2.3 inexplicable occurrences, 3.1 backwards causation, 3.2 causal loops, 4.1 time travel and time, 4.2 time travel and change, 5. where are the time travellers, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is time travel.

There is a number of rather different scenarios which would seem, intuitively, to count as ‘time travel’—and a number of scenarios which, while sharing certain features with some of the time travel cases, seem nevertheless not to count as genuine time travel: [ 1 ]

Time travel Doctor . Doctor Who steps into a machine in 2024. Observers outside the machine see it disappear. Inside the machine, time seems to Doctor Who to pass for ten minutes. Observers in 1984 (or 3072) see the machine appear out of nowhere. Doctor Who steps out. [ 2 ] Leap . The time traveller takes hold of a special device (or steps into a machine) and suddenly disappears; she appears at an earlier (or later) time. Unlike in Doctor , the time traveller experiences no lapse of time between her departure and arrival: from her point of view, she instantaneously appears at the destination time. [ 3 ] Putnam . Oscar Smith steps into a machine in 2024. From his point of view, things proceed much as in Doctor : time seems to Oscar Smith to pass for a while; then he steps out in 1984. For observers outside the machine, things proceed differently. Observers of Oscar’s arrival in the past see a time machine suddenly appear out of nowhere and immediately divide into two copies of itself: Oscar Smith steps out of one; and (through the window) they see inside the other something that looks just like what they would see if a film of Oscar Smith were played backwards (his hair gets shorter; food comes out of his mouth and goes back into his lunch box in a pristine, uneaten state; etc.). Observers of Oscar’s departure from the future do not simply see his time machine disappear after he gets into it: they see it collide with the apparently backwards-running machine just described, in such a way that both are simultaneously annihilated. [ 4 ] Gödel . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship (not a special time machine) and flies off on a certain course. At no point does she disappear (as in Leap ) or ‘turn back in time’ (as in Putnam )—yet thanks to the overall structure of spacetime (as conceived in the General Theory of Relativity), the traveller arrives at a point in the past (or future) of her departure. (Compare the way in which someone can travel continuously westwards, and arrive to the east of her departure point, thanks to the overall curved structure of the surface of the earth.) [ 5 ] Einstein . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship and flies off at high speed on a round trip. When he returns to Earth, thanks to certain effects predicted by the Special Theory of Relativity, only a very small amount of time has elapsed for him—he has aged only a few months—while a great deal of time has passed on Earth: it is now hundreds of years in the future of his time of departure. [ 6 ] Not time travel Sleep . One is very tired, and falls into a deep sleep. When one awakes twelve hours later, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Coma . One is in a coma for a number of years and then awakes, at which point it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Cryogenics . One is cryogenically frozen for hundreds of years. Upon being woken, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Virtual . One enters a highly realistic, interactive virtual reality simulator in which some past era has been recreated down to the finest detail. Crystal . One looks into a crystal ball and sees what happened at some past time, or will happen at some future time. (Imagine that the crystal ball really works—like a closed-circuit security monitor, except that the vision genuinely comes from some past or future time. Even so, the person looking at the crystal ball is not thereby a time traveller.) Waiting . One enters one’s closet and stays there for seven hours. When one emerges, one has ‘arrived’ seven hours in the future of one’s ‘departure’. Dateline . One departs at 8pm on Monday, flies for fourteen hours, and arrives at 10pm on Monday.

A satisfactory definition of time travel would, at least, need to classify the cases in the right way. There might be some surprises—perhaps, on the best definition of ‘time travel’, Cryogenics turns out to be time travel after all—but it should certainly be the case, for example, that Gödel counts as time travel and that Sleep and Waiting do not. [ 7 ]

In fact there is no entirely satisfactory definition of ‘time travel’ in the literature. The most popular definition is the one given by Lewis (1976, 145–6):

What is time travel? Inevitably, it involves a discrepancy between time and time. Any traveller departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival…is the duration of the journey. But if he is a time traveller, the separation in time between departure and arrival does not equal the duration of his journey.…How can it be that the same two events, his departure and his arrival, are separated by two unequal amounts of time?…I reply by distinguishing time itself, external time as I shall also call it, from the personal time of a particular time traveller: roughly, that which is measured by his wristwatch. His journey takes an hour of his personal time, let us say…But the arrival is more than an hour after the departure in external time, if he travels toward the future; or the arrival is before the departure in external time…if he travels toward the past.

This correctly excludes Waiting —where the length of the ‘journey’ precisely matches the separation between ‘arrival’ and ‘departure’—and Crystal , where there is no journey at all—and it includes Doctor . It has trouble with Gödel , however—because when the overall structure of spacetime is as twisted as it is in the sort of case Gödel imagined, the notion of external time (“time itself”) loses its grip.

Another definition of time travel that one sometimes encounters in the literature (Arntzenius, 2006, 602) (Smeenk and Wüthrich, 2011, 5, 26) equates time travel with the existence of CTC’s: closed timelike curves. A curve in this context is a line in spacetime; it is timelike if it could represent the career of a material object; and it is closed if it returns to its starting point (i.e. in spacetime—not merely in space). This now includes Gödel —but it excludes Einstein .

The lack of an adequate definition of ‘time travel’ does not matter for our purposes here. [ 8 ] It suffices that we have clear cases of (what would count as) time travel—and that these cases give rise to all the problems that we shall wish to discuss.

Some authors (in philosophy, physics and science fiction) consider ‘time travel’ scenarios in which there are two temporal dimensions (e.g. Meiland (1974)), and others consider scenarios in which there are multiple ‘parallel’ universes—each one with its own four-dimensional spacetime (e.g. Deutsch and Lockwood (1994)). There is a question whether travelling to another version of 2001 (i.e. not the very same version one experienced in the past)—a version at a different point on the second time dimension, or in a different parallel universe—is really time travel, or whether it is more akin to Virtual . In any case, this kind of scenario does not give rise to many of the problems thrown up by the idea of travelling to the very same past one experienced in one’s younger days. It is these problems that form the primary focus of the present entry, and so we shall not have much to say about other kinds of ‘time travel’ scenario in what follows.

One objection to the possibility of time travel flows directly from attempts to define it in anything like Lewis’s way. The worry is that because time travel involves “a discrepancy between time and time”, time travel scenarios are simply incoherent. The time traveller traverses thirty years in one year; she is 51 years old 21 years after her birth; she dies at the age of 100, 200 years before her birth; and so on. The objection is that these are straightforward contradictions: the basic description of what time travel involves is inconsistent; therefore time travel is logically impossible. [ 9 ]

There must be something wrong with this objection, because it would show Einstein to be logically impossible—whereas this sort of future-directed time travel has actually been observed (albeit on a much smaller scale—but that does not affect the present point) (Hafele and Keating, 1972b,a). The most common response to the objection is that there is no contradiction because the interval of time traversed by the time traveller and the duration of her journey are measured with respect to different frames of reference: there is thus no reason why they should coincide. A similar point applies to the discrepancy between the time elapsed since the time traveller’s birth and her age upon arrival. There is no more of a contradiction here than in the fact that Melbourne is both 800 kilometres away from Sydney—along the main highway—and 1200 kilometres away—along the coast road. [ 10 ]

Before leaving the question ‘What is time travel?’ we should note the crucial distinction between changing the past and participating in (aka affecting or influencing) the past. [ 11 ] In the popular imagination, backwards time travel would allow one to change the past: to right the wrongs of history, to prevent one’s younger self doing things one later regretted, and so on. In a model with a single past, however, this idea is incoherent: the very description of the case involves a contradiction (e.g. the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976, and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976). It is not as if there are two versions of the past: the original one, without the time traveller present, and then a second version, with the time traveller playing a role. There is just one past—and two perspectives on it: the perspective of the younger self, and the perspective of the older time travelling self. If these perspectives are inconsistent (e.g. an event occurs in one but not the other) then the time travel scenario is incoherent.

This means that time travellers can do less than we might have hoped: they cannot right the wrongs of history; they cannot even stir a speck of dust on a certain day in the past if, on that day, the speck was in fact unmoved. But this does not mean that time travellers must be entirely powerless in the past: while they cannot do anything that did not actually happen, they can (in principle) do anything that did happen. Time travellers cannot change the past: they cannot make it different from the way it was—but they can participate in it: they can be amongst the people who did make the past the way it was. [ 12 ]

What about models involving two temporal dimensions, or parallel universes—do they allow for coherent scenarios in which the past is changed? [ 13 ] There is certainly no contradiction in saying that the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 1 (or at hypertime A ), and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 2 (or at hypertime B ). The question is whether this kind of story involves changing the past in the sense originally envisaged: righting the wrongs of history, preventing subsequently regretted actions, and so on. Goddu (2003) and van Inwagen (2010) argue that it does (in the context of particular hypertime models), while Smith (1997, 365–6; 2015) argues that it does not: that it involves avoiding the past—leaving it untouched while travelling to a different version of the past in which things proceed differently.

2. The Grandfather Paradox

The most important objection to the logical possibility of backwards time travel is the so-called Grandfather paradox. This paradox has actually convinced many people that backwards time travel is impossible:

The dead giveaway that true time-travel is flatly impossible arises from the well-known “paradoxes” it entails. The classic example is “What if you go back into the past and kill your grandfather when he was still a little boy?”…So complex and hopeless are the paradoxes…that the easiest way out of the irrational chaos that results is to suppose that true time-travel is, and forever will be, impossible. (Asimov 1995 [2003, 276–7]) travel into one’s past…would seem to give rise to all sorts of logical problems, if you were able to change history. For example, what would happen if you killed your parents before you were born. It might be that one could avoid such paradoxes by some modification of the concept of free will. But this will not be necessary if what I call the chronology protection conjecture is correct: The laws of physics prevent closed timelike curves from appearing . (Hawking, 1992, 604) [ 14 ]

The paradox comes in different forms. Here’s one version:

If time travel was logically possible then the time traveller could return to the past and in a suicidal rage destroy his time machine before it was completed and murder his younger self. But if this was so a necessary condition for the time trip to have occurred at all is removed, and we should then conclude that the time trip did not occur. Hence if the time trip did occur, then it did not occur. Hence it did not occur, and it is necessary that it did not occur. To reply, as it is standardly done, that our time traveller cannot change the past in this way, is a petitio principii . Why is it that the time traveller is constrained in this way? What mysterious force stills his sudden suicidal rage? (Smith, 1985, 58)

The idea is that backwards time travel is impossible because if it occurred, time travellers would attempt to do things such as kill their younger selves (or their grandfathers etc.). We know that doing these things—indeed, changing the past in any way—is impossible. But were there time travel, there would then be nothing left to stop these things happening. If we let things get to the stage where the time traveller is facing Grandfather with a loaded weapon, then there is nothing left to prevent the impossible from occurring. So we must draw the line earlier: it must be impossible for someone to get into this situation at all; that is, backwards time travel must be impossible.

In order to defend the possibility of time travel in the face of this argument we need to show that time travel is not a sure route to doing the impossible. So, given that a time traveller has gone to the past and is facing Grandfather, what could stop her killing Grandfather? Some science fiction authors resort to the idea of chaperones or time guardians who prevent time travellers from changing the past—or to mysterious forces of logic. But it is hard to take these ideas seriously—and more importantly, it is hard to make them work in detail when we remember that changing the past is impossible. (The chaperone is acting to ensure that the past remains as it was—but the only reason it ever was that way is because of his very actions.) [ 15 ] Fortunately there is a better response—also to be found in the science fiction literature, and brought to the attention of philosophers by Lewis (1976). What would stop the time traveller doing the impossible? She would fail “for some commonplace reason”, as Lewis (1976, 150) puts it. Her gun might jam, a noise might distract her, she might slip on a banana peel, etc. Nothing more than such ordinary occurrences is required to stop the time traveller killing Grandfather. Hence backwards time travel does not entail the occurrence of impossible events—and so the above objection is defused.

A problem remains. Suppose Tim, a time-traveller, is facing his grandfather with a loaded gun. Can Tim kill Grandfather? On the one hand, yes he can. He is an excellent shot; there is no chaperone to stop him; the laws of logic will not magically stay his hand; he hates Grandfather and will not hesitate to pull the trigger; etc. On the other hand, no he can’t. To kill Grandfather would be to change the past, and no-one can do that (not to mention the fact that if Grandfather died, then Tim would not have been born). So we have a contradiction: Tim can kill Grandfather and Tim cannot kill Grandfather. Time travel thus leads to a contradiction: so it is impossible.

Note the difference between this version of the Grandfather paradox and the version considered above. In the earlier version, the contradiction happens if Tim kills Grandfather. The solution was to say that Tim can go into the past without killing Grandfather—hence time travel does not entail a contradiction. In the new version, the contradiction happens as soon as Tim gets to the past. Of course Tim does not kill Grandfather—but we still have a contradiction anyway: for he both can do it, and cannot do it. As Lewis puts it:

Could a time traveler change the past? It seems not: the events of a past moment could no more change than numbers could. Yet it seems that he would be as able as anyone to do things that would change the past if he did them. If a time traveler visiting the past both could and couldn’t do something that would change it, then there cannot possibly be such a time traveler. (Lewis, 1976, 149)

Lewis’s own solution to this problem has been widely accepted. [ 16 ] It turns on the idea that to say that something can happen is to say that its occurrence is compossible with certain facts, where context determines (more or less) which facts are the relevant ones. Tim’s killing Grandfather in 1921 is compossible with the facts about his weapon, training, state of mind, and so on. It is not compossible with further facts, such as the fact that Grandfather did not die in 1921. Thus ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ is true in one sense (relative to one set of facts) and false in another sense (relative to another set of facts)—but there is no single sense in which it is both true and false. So there is no contradiction here—merely an equivocation.

Another response is that of Vihvelin (1996), who argues that there is no contradiction here because ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ is simply false (i.e. contra Lewis, there is no legitimate sense in which it is true). According to Vihvelin, for ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ to be true, there must be at least some occasions on which ‘If Tim had tried to kill Grandfather, he would or at least might have succeeded’ is true—but, Vihvelin argues, at any world remotely like ours, the latter counterfactual is always false. [ 17 ]

Return to the original version of the Grandfather paradox and Lewis’s ‘commonplace reasons’ response to it. This response engenders a new objection—due to Horwich (1987)—not to the possibility but to the probability of backwards time travel.

Think about correlated events in general. Whenever we see two things frequently occurring together, this is because one of them causes the other, or some third thing causes both. Horwich calls this the Principle of V-Correlation:

if events of type A and B are associated with one another, then either there is always a chain of events between them…or else we find an earlier event of type C that links up with A and B by two such chains of events. What we do not see is…an inverse fork—in which A and B are connected only with a characteristic subsequent event, but no preceding one. (Horwich, 1987, 97–8)

For example, suppose that two students turn up to class wearing the same outfits. That could just be a coincidence (i.e. there is no common cause, and no direct causal link between the two events). If it happens every week for the whole semester, it is possible that it is a coincidence, but this is extremely unlikely . Normally, we see this sort of extensive correlation only if either there is a common cause (e.g. both students have product endorsement deals with the same clothing company, or both slavishly copy the same influencer) or a direct causal link (e.g. one student is copying the other).

Now consider the time traveller setting off to kill her younger self. As discussed, no contradiction need ensue—this is prevented not by chaperones or mysterious forces, but by a run of ordinary occurrences in which the trigger falls off the time traveller’s gun, a gust of wind pushes her bullet off course, she slips on a banana peel, and so on. But now consider this run of ordinary occurrences. Whenever the time traveller contemplates auto-infanticide, someone nearby will drop a banana peel ready for her to slip on, or a bird will begin to fly so that it will be in the path of the time traveller’s bullet by the time she fires, and so on. In general, there will be a correlation between auto-infanticide attempts and foiling occurrences such as the presence of banana peels—and this correlation will be of the type that does not involve a direct causal connection between the correlated events or a common cause of both. But extensive correlations of this sort are, as we saw, extremely rare—so backwards time travel will happen about as often as you will see two people wear the same outfits to class every day of semester, without there being any causal connection between what one wears and what the other wears.

We can set out Horwich’s argument this way:

- If time travel were ever to occur, we should see extensive uncaused correlations.

- It is extremely unlikely that we should ever see extensive uncaused correlations.

- Therefore time travel is extremely unlikely to occur.

The conclusion is not that time travel is impossible, but that we should treat it the way we treat the possibility of, say, tossing a fair coin and getting heads one thousand times in a row. As Price (1996, 278 n.7) puts it—in the context of endorsing Horwich’s conclusion: “the hypothesis of time travel can be made to imply propositions of arbitrarily low probability. This is not a classical reductio, but it is as close as science ever gets.”

Smith (1997) attacks both premisses of Horwich’s argument. Against the first premise, he argues that backwards time travel, in itself, does not entail extensive uncaused correlations. Rather, when we look more closely, we see that time travel scenarios involving extensive uncaused correlations always build in prior coincidences which are themselves highly unlikely. Against the second premise, he argues that, from the fact that we have never seen extensive uncaused correlations, it does not follow that we never shall. This is not inductive scepticism: let us assume (contra the inductive sceptic) that in the absence of any specific reason for thinking things should be different in the future, we are entitled to assume they will continue being the same; still we cannot dismiss a specific reason for thinking the future will be a certain way simply on the basis that things have never been that way in the past. You might reassure an anxious friend that the sun will certainly rise tomorrow because it always has in the past—but you cannot similarly refute an astronomer who claims to have discovered a specific reason for thinking that the earth will stop rotating overnight.

Sider (2002, 119–20) endorses Smith’s second objection. Dowe (2003) criticises Smith’s first objection, but agrees with the second, concluding overall that time travel has not been shown to be improbable. Ismael (2003) reaches a similar conclusion. Goddu (2007) criticises Smith’s first objection to Horwich. Further contributions to the debate include Arntzenius (2006), Smeenk and Wüthrich (2011, §2.2) and Elliott (2018). For other arguments to the same conclusion as Horwich’s—that time travel is improbable—see Ney (2000) and Effingham (2020).

Return again to the original version of the Grandfather paradox and Lewis’s ‘commonplace reasons’ response to it. This response engenders a further objection. The autoinfanticidal time traveller is attempting to do something impossible (render herself permanently dead from an age younger than her age at the time of the attempts). Suppose we accept that she will not succeed and that what will stop her is a succession of commonplace occurrences. The previous objection was that such a succession is improbable . The new objection is that the exclusion of the time traveler from successfully committing auto-infanticide is mysteriously inexplicable . The worry is as follows. Each particular event that foils the time traveller is explicable in a perfectly ordinary way; but the inevitable combination of these events amounts to a ring-fencing of the forbidden zone of autoinfanticide—and this ring-fencing is mystifying. It’s like a grand conspiracy to stop the time traveler from doing what she wants to do—and yet there are no conspirators: no time lords, no magical forces of logic. This is profoundly perplexing. Riggs (1997, 52) writes: “Lewis’s account may do for a once only attempt, but is untenable as a general explanation of Tim’s continual lack of success if he keeps on trying.” Ismael (2003, 308) writes: “Considered individually, there will be nothing anomalous in the explanations…It is almost irresistible to suppose, however, that there is something anomalous in the cases considered collectively, i.e., in our unfailing lack of success.” See also Gorovitz (1964, 366–7), Horwich (1987, 119–21) and Carroll (2010, 86).

There have been two different kinds of defense of time travel against the objection that it involves mysteriously inexplicable occurrences. Baron and Colyvan (2016, 70) agree with the objectors that a purely causal explanation of failure—e.g. Tim fails to kill Grandfather because first he slips on a banana peel, then his gun jams, and so on—is insufficient. However they argue that, in addition, Lewis offers a non-causal—a logical —explanation of failure: “What explains Tim’s failure to kill his grandfather, then, is something about logic; specifically: Tim fails to kill his grandfather because the law of non-contradiction holds.” Smith (2017) argues that the appearance of inexplicability is illusory. There are no scenarios satisfying the description ‘a time traveller commits autoinfanticide’ (or changes the past in any other way) because the description is self-contradictory (e.g. it involves the time traveller permanently dying at 20 and also being alive at 40). So whatever happens it will not be ‘that’. There is literally no way for the time traveller not to fail. Hence there is no need for—or even possibility of—a substantive explanation of why failure invariably occurs, and such failure is not perplexing.

3. Causation

Backwards time travel scenarios give rise to interesting issues concerning causation. In this section we examine two such issues.

Earlier we distinguished changing the past and affecting the past, and argued that while the former is impossible, backwards time travel need involve only the latter. Affecting the past would be an example of backwards causation (i.e. causation where the effect precedes its cause)—and it has been argued that this too is impossible, or at least problematic. [ 18 ] The classic argument against backwards causation is the bilking argument . [ 19 ] Faced with the claim that some event A causes an earlier event B , the proponent of the bilking objection recommends an attempt to decorrelate A and B —that is, to bring about A in cases in which B has not occurred, and to prevent A in cases in which B has occurred. If the attempt is successful, then B often occurs despite the subsequent nonoccurrence of A , and A often occurs without B occurring, and so A cannot be the cause of B . If, on the other hand, the attempt is unsuccessful—if, that is, A cannot be prevented when B has occurred, nor brought about when B has not occurred—then, it is argued, it must be B that is the cause of A , rather than vice versa.

The bilking procedure requires repeated manipulation of event A . Thus, it cannot get under way in cases in which A is either unrepeatable or unmanipulable. Furthermore, the procedure requires us to know whether or not B has occurred, prior to manipulating A —and thus, it cannot get under way in cases in which it cannot be known whether or not B has occurred until after the occurrence or nonoccurrence of A (Dummett, 1964). These three loopholes allow room for many claims of backwards causation that cannot be touched by the bilking argument, because the bilking procedure cannot be performed at all. But what about those cases in which it can be performed? If the procedure succeeds—that is, A and B are decorrelated—then the claim that A causes B is refuted, or at least weakened (depending upon the details of the case). But if the bilking attempt fails, it does not follow that it must be B that is the cause of A , rather than vice versa. Depending upon the situation, that B causes A might become a viable alternative to the hypothesis that A causes B —but there is no reason to think that this alternative must always be the superior one. For example, suppose that I see a photo of you in a paper dated well before your birth, accompanied by a report of your arrival from the future. I now try to bilk your upcoming time trip—but I slip on a banana peel while rushing to push you away from your time machine, my time travel horror stories only inspire you further, and so on. Or again, suppose that I know that you were not in Sydney yesterday. I now try to get you to go there in your time machine—but first I am struck by lightning, then I fall down a manhole, and so on. What does all this prove? Surely not that your arrival in the past causes your departure from the future. Depending upon the details of the case, it seems that we might well be entitled to describe it as involving backwards time travel and backwards causation. At least, if we are not so entitled, this must be because of other facts about the case: it would not follow simply from the repeated coincidental failures of my bilking attempts.

Backwards time travel would apparently allow for the possibility of causal loops, in which things come from nowhere. The things in question might be objects—imagine a time traveller who steals a time machine from the local museum in order to make his time trip and then donates the time machine to the same museum at the end of the trip (i.e. in the past). In this case the machine itself is never built by anyone—it simply exists. The things in question might be information—imagine a time traveller who explains the theory behind time travel to her younger self: theory that she herself knows only because it was explained to her in her youth by her time travelling older self. The things in question might be actions. Imagine a time traveller who visits his younger self. When he encounters his younger self, he suddenly has a vivid memory of being punched on the nose by a strange visitor. He realises that this is that very encounter—and resignedly proceeds to punch his younger self. Why did he do it? Because he knew that it would happen and so felt that he had to do it—but he only knew it would happen because he in fact did it. [ 20 ]

One might think that causal loops are impossible—and hence that insofar as backwards time travel entails such loops, it too is impossible. [ 21 ] There are two issues to consider here. First, does backwards time travel entail causal loops? Lewis (1976, 148) raises the question whether there must be causal loops whenever there is backwards causation; in response to the question, he says simply “I am not sure.” Mellor (1998, 131) appears to claim a positive answer to the question. [ 22 ] Hanley (2004, 130) defends a negative answer by telling a time travel story in which there is backwards time travel and backwards causation, but no causal loops. [ 23 ] Monton (2009) criticises Hanley’s counterexample, but also defends a negative answer via different counterexamples. Effingham (2020) too argues for a negative answer.

Second, are causal loops impossible, or in some other way objectionable? One objection is that causal loops are inexplicable . There have been two main kinds of response to this objection. One is to agree but deny that this is a problem. Lewis (1976, 149) accepts that a loop (as a whole) would be inexplicable—but thinks that this inexplicability (like that of the Big Bang or the decay of a tritium atom) is merely strange, not impossible. In a similar vein, Meyer (2012, 263) argues that if someone asked for an explanation of a loop (as a whole), “the blame would fall on the person asking the question, not on our inability to answer it.” The second kind of response (Hanley, 2004, §5) is to deny that (all) causal loops are inexplicable. A second objection to causal loops, due to Mellor (1998, ch.12), is that in such loops the chances of events would fail to be related to their frequencies in accordance with the law of large numbers. Berkovitz (2001) and Dowe (2001) both argue that Mellor’s objection fails to establish the impossibility of causal loops. [ 24 ] Effingham (2020) considers—and rebuts—some additional objections to the possibility of causal loops.

4. Time and Change

Gödel (1949a [1990a])—in which Gödel presents models of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in which there exist CTC’s—can well be regarded as initiating the modern academic literature on time travel, in both philosophy and physics. In a companion paper, Gödel discusses the significance of his results for more general issues in the philosophy of time (Gödel 1949b [1990b]). For the succeeding half century, the time travel literature focussed predominantly on objections to the possibility (or probability) of time travel. More recently, however, there has been renewed interest in the connections between time travel and more general issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We examine some of these in the present section. [ 25 ]

The first thing that we need to do is set up the various metaphysical positions whose relationships with time travel will then be discussed. Consider two metaphysical questions:

- Are the past, present and future equally real?

- Is there an objective flow or passage of time, and an objective now?

We can label some views on the first question as follows. Eternalism is the view that past and future times, objects and events are just as real as the present time and present events and objects. Nowism is the view that only the present time and present events and objects exist. Now-and-then-ism is the view that the past and present exist but the future does not. We can also label some views on the second question. The A-theory answers in the affirmative: the flow of time and division of events into past (before now), present (now) and future (after now) are objective features of reality (as opposed to mere features of our experience). Furthermore, they are linked: the objective flow of time arises from the movement, through time, of the objective now (from the past towards the future). The B-theory answers in the negative: while we certainly experience now as special, and time as flowing, the B-theory denies that what is going on here is that we are detecting objective features of reality in a way that corresponds transparently to how those features are in themselves. The flow of time and the now are not objective features of reality; they are merely features of our experience. By combining answers to our first and second questions we arrive at positions on the metaphysics of time such as: [ 26 ]

- the block universe view: eternalism + B-theory

- the moving spotlight view: eternalism + A-theory

- the presentist view: nowism + A-theory

- the growing block view: now-and-then-ism + A-theory.

So much for positions on time itself. Now for some views on temporal objects: objects that exist in (and, in general, change over) time. Three-dimensionalism is the view that persons, tables and other temporal objects are three-dimensional entities. On this view, what you see in the mirror is a whole person. [ 27 ] Tomorrow, when you look again, you will see the whole person again. On this view, persons and other temporal objects are wholly present at every time at which they exist. Four-dimensionalism is the view that persons, tables and other temporal objects are four-dimensional entities, extending through three dimensions of space and one dimension of time. On this view, what you see in the mirror is not a whole person: it is just a three-dimensional temporal part of a person. Tomorrow, when you look again, you will see a different such temporal part. Say that an object persists through time if it is around at some time and still around at a later time. Three- and four-dimensionalists agree that (some) objects persist, but they differ over how objects persist. According to three-dimensionalists, objects persist by enduring : an object persists from t 1 to t 2 by being wholly present at t 1 and t 2 and every instant in between. According to four-dimensionalists, objects persist by perduring : an object persists from t 1 to t 2 by having temporal parts at t 1 and t 2 and every instant in between. Perduring can be usefully compared with being extended in space: a road extends from Melbourne to Sydney not by being wholly located at every point in between, but by having a spatial part at every point in between.

It is natural to combine three-dimensionalism with presentism and four-dimensionalism with the block universe view—but other combinations of views are certainly possible.

Gödel (1949b [1990b]) argues from the possibility of time travel (more precisely, from the existence of solutions to the field equations of General Relativity in which there exist CTC’s) to the B-theory: that is, to the conclusion that there is no objective flow or passage of time and no objective now. Gödel begins by reviewing an argument from Special Relativity to the B-theory: because the notion of simultaneity becomes a relative one in Special Relativity, there is no room for the idea of an objective succession of “nows”. He then notes that this argument is disrupted in the context of General Relativity, because in models of the latter theory to date, the presence of matter does allow recovery of an objectively distinguished series of “nows”. Gödel then proposes a new model (Gödel 1949a [1990a]) in which no such recovery is possible. (This is the model that contains CTC’s.) Finally, he addresses the issue of how one can infer anything about the nonexistence of an objective flow of time in our universe from the existence of a merely possible universe in which there is no objectively distinguished series of “nows”. His main response is that while it would not be straightforwardly contradictory to suppose that the existence of an objective flow of time depends on the particular, contingent arrangement and motion of matter in the world, this would nevertheless be unsatisfactory. Responses to Gödel have been of two main kinds. Some have objected to the claim that there is no objective flow of time in his model universe (e.g. Savitt (2005); see also Savitt (1994)). Others have objected to the attempt to transfer conclusions about that model universe to our own universe (e.g. Earman (1995, 197–200); for a partial response to Earman see Belot (2005, §3.4)). [ 28 ]

Earlier we posed two questions:

Gödel’s argument is related to the second question. Let’s turn now to the first question. Godfrey-Smith (1980, 72) writes “The metaphysical picture which underlies time travel talk is that of the block universe [i.e. eternalism, in the terminology of the present entry], in which the world is conceived as extended in time as it is in space.” In his report on the Analysis problem to which Godfrey-Smith’s paper is a response, Harrison (1980, 67) replies that he would like an argument in support of this assertion. Here is an argument: [ 29 ]

A fundamental requirement for the possibility of time travel is the existence of the destination of the journey. That is, a journey into the past or the future would have to presuppose that the past or future were somehow real. (Grey, 1999, 56)

Dowe (2000, 442–5) responds that the destination does not have to exist at the time of departure: it only has to exist at the time of arrival—and this is quite compatible with non-eternalist views. And Keller and Nelson (2001, 338) argue that time travel is compatible with presentism:

There is four-dimensional [i.e. eternalist, in the terminology of the present entry] time-travel if the appropriate sorts of events occur at the appropriate sorts of times; events like people hopping into time-machines and disappearing, people reappearing with the right sorts of memories, and so on. But the presentist can have just the same patterns of events happening at just the same times. Or at least, it can be the case on the presentist model that the right sorts of events will happen, or did happen, or are happening, at the rights sorts of times. If it suffices for four-dimensionalist time-travel that Jennifer disappears in 2054 and appears in 1985 with the right sorts of memories, then why shouldn’t it suffice for presentist time-travel that Jennifer will disappear in 2054, and that she did appear in 1985 with the right sorts of memories?

Sider (2005) responds that there is still a problem reconciling presentism with time travel conceived in Lewis’s way: that conception of time travel requires that personal time is similar to external time—but presentists have trouble allowing this. Further contributions to the debate whether presentism—and other versions of the A-theory—are compatible with time travel include Monton (2003), Daniels (2012), Hall (2014) and Wasserman (2018) on the side of compatibility, and Miller (2005), Slater (2005), Miller (2008), Hales (2010) and Markosian (2020) on the side of incompatibility.

Leibniz’s Law says that if x = y (i.e. x and y are identical—one and the same entity) then x and y have exactly the same properties. There is a superficial conflict between this principle of logic and the fact that things change. If Bill is at one time thin and at another time not so—and yet it is the very same person both times—it looks as though the very same entity (Bill) both possesses and fails to possess the property of being thin. Three-dimensionalists and four-dimensionalists respond to this problem in different ways. According to the four-dimensionalist, what is thin is not Bill (who is a four-dimensional entity) but certain temporal parts of Bill; and what is not thin are other temporal parts of Bill. So there is no single entity that both possesses and fails to possess the property of being thin. Three-dimensionalists have several options. One is to deny that there are such properties as ‘thin’ (simpliciter): there are only temporally relativised properties such as ‘thin at time t ’. In that case, while Bill at t 1 and Bill at t 2 are the very same entity—Bill is wholly present at each time—there is no single property that this one entity both possesses and fails to possess: Bill possesses the property ‘thin at t 1 ’ and lacks the property ‘thin at t 2 ’. [ 30 ]

Now consider the case of a time traveller Ben who encounters his younger self at time t . Suppose that the younger self is thin and the older self not so. The four-dimensionalist can accommodate this scenario easily. Just as before, what we have are two different three-dimensional parts of the same four-dimensional entity, one of which possesses the property ‘thin’ and the other of which does not. The three-dimensionalist, however, faces a problem. Even if we relativise properties to times, we still get the contradiction that Ben possesses the property ‘thin at t ’ and also lacks that very same property. [ 31 ] There are several possible options for the three-dimensionalist here. One is to relativise properties not to external times but to personal times (Horwich, 1975, 434–5); another is to relativise properties to spatial locations as well as to times (or simply to spacetime points). Sider (2001, 101–6) criticises both options (and others besides), concluding that time travel is incompatible with three-dimensionalism. Markosian (2004) responds to Sider’s argument; [ 32 ] Miller (2006) also responds to Sider and argues for the compatibility of time travel and endurantism; Gilmore (2007) seeks to weaken the case against endurantism by constructing analogous arguments against perdurantism. Simon (2005) finds problems with Sider’s arguments, but presents different arguments for the same conclusion; Effingham and Robson (2007) and Benovsky (2011) also offer new arguments for this conclusion. For further discussion see Wasserman (2018) and Effingham (2020). [ 33 ]

We have seen arguments to the conclusions that time travel is impossible, improbable and inexplicable. Here’s an argument to the conclusion that backwards time travel simply will not occur. If backwards time travel is ever going to occur, we would already have seen the time travellers—but we have seen none such. [ 34 ] The argument is a weak one. [ 35 ] For a start, it is perhaps conceivable that time travellers have already visited the Earth [ 36 ] —but even granting that they have not, this is still compatible with the future actuality of backwards time travel. First, it may be that time travel is very expensive, difficult or dangerous—or for some other reason quite rare—and that by the time it is available, our present period of history is insufficiently high on the list of interesting destinations. Second, it may be—and indeed existing proposals in the physics literature have this feature—that backwards time travel works by creating a CTC that lies entirely in the future: in this case, backwards time travel becomes possible after the creation of the CTC, but travel to a time earlier than the time at which the CTC is created is not possible. [ 37 ]

- Adams, Robert Merrihew, 1997, “Thisness and time travel”, Philosophia , 25: 407–15.

- Arntzenius, Frank, 2006, “Time travel: Double your fun”, Philosophy Compass , 1: 599–616. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2006.00045.x

- Asimov, Isaac, 1995 [2003], Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection , New York: Harper Collins.

- Baron, Sam and Colyvan, Mark, 2016, “Time enough for explanation”, Journal of Philosophy , 113: 61–88.

- Belot, Gordon, 2005, “Dust, time and symmetry”, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science , 56: 255–91.

- Benovsky, Jiri, 2011, “Endurance and time travel”, Kriterion , 24: 65–72.

- Berkovitz, Joseph, 2001, “On chance in causal loops”, Mind , 110: 1–23.

- Black, Max, 1956, “Why cannot an effect precede its cause?”, Analysis , 16: 49–58.

- Brier, Bob, 1973, “Magicians, alarm clocks, and backward causation”, Southern Journal of Philosophy , 11: 359–64.

- Carlson, Erik, 2005, “A new time travel paradox resolved”, Philosophia , 33: 263–73.

- Carroll, John W., 2010, “Context, conditionals, fatalism, time travel, and freedom”, in Time and Identity , Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O’Rourke, and Harry S. Silverstein, eds., Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 79–93.

- Craig, William L., 1997, “Adams on actualism and presentism”, Philosophia , 25: 401–5.

- Daniels, Paul R., 2012, “Back to the present: Defending presentist time travel”, Disputatio , 4: 469–84.

- Deutsch, David and Lockwood, Michael, 1994, “The quantum physics of time travel”, Scientific American , 270(3): 50–6.

- Dowe, Phil, 2000, “The case for time travel”, Philosophy , 75: 441–51.

- –––, 2001, “Causal loops and the independence of causal facts”, Philosophy of Science , 68: S89–S97.

- –––, 2003, “The coincidences of time travel”, Philosophy of Science , 70: 574–89.

- Dummett, Michael, 1964, “Bringing about the past”, Philosophical Review , 73: 338–59.

- Dwyer, Larry, 1977, “How to affect, but not change, the past”, Southern Journal of Philosophy , 15: 383–5.

- Earman, John, 1995, Bangs, Crunches, Whimpers, and Shrieks: Singularities and Acausalities in Relativistic Spacetimes , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Effingham, Nikk, 2020, Time Travel: Probability and Impossibility , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Effingham, Nikk and Robson, Jon, 2007, “A mereological challenge to endurantism”, Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 85: 633–40.

- Ehring, Douglas, 1997, “Personal identity and time travel”, Philosophical Studies , 52: 427–33.

- Elliott, Katrina, 2019, “How to Know That Time Travel Is Unlikely Without Knowing Why”, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly , 100: 90–113.

- Fulmer, Gilbert, 1980, “Understanding time travel”, Southwestern Journal of Philosophy , 11: 151–6.

- Gilmore, Cody, 2007, “Time travel, coinciding objects, and persistence”, in Oxford Studies in Metaphysics , Dean W. Zimmerman, ed., Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 3, 177–98.

- Goddu, G.C., 2003, “Time travel and changing the past (or how to kill yourself and live to tell the tale)”, Ratio , 16: 16–32.

- –––, 2007, “Banana peels and time travel”, Dialectica , 61: 559–72.

- Gödel, Kurt, 1949a [1990a], “An example of a new type of cosmological solutions of Einstein’s field equations of gravitation”, in Kurt Gödel: Collected Works (Volume II), Solomon Feferman, et al. (eds.), New York: Oxford University Press, 190–8; originally published in Reviews of Modern Physics , 21 (1949): 447–450.

- –––, 1949b [1990b], “A remark about the relationship between relativity theory and idealistic philosophy”, in Kurt Gödel: Collected Works (Volume II), Solomon Feferman, et al. (eds.), New York: Oxford University Press, 202–7; originally published in P. Schilpp (ed.), Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist , La Salle: Open Court, 1949, 555–562.

- Godfrey-Smith, William, 1980, “Travelling in time”, Analysis , 40: 72–3.

- Gorovitz, Samuel, 1964, “Leaving the past alone”, Philosophical Review , 73: 360–71.

- Grey, William, 1999, “Troubles with time travel”, Philosophy , 74: 55–70.

- Hafele, J. C. and Keating, Richard E., 1972a, “Around-the-world atomic clocks: Observed relativistic time gains”, Science , 177: 168–70.

- –––, 1972b, “Around-the-world atomic clocks: Predicted relativistic time gains”, Science , 177: 166–8.

- Hales, Steven D., 2010, “No time travel for presentists”, Logos & Episteme , 1: 353–60.

- Hall, Thomas, 2014, “In Defense of the Compossibility of Presentism and Time Travel”, Logos & Episteme , 2: 141–59.

- Hanley, Richard, 2004, “No end in sight: Causal loops in philosophy, physics and fiction”, Synthese , 141: 123–52.

- Harrison, Jonathan, 1980, “Report on analysis ‘problem’ no. 18”, Analysis , 40: 65–9.

- Hawking, S.W., 1992, “Chronology protection conjecture”, Physical Review D , 46: 603–11.

- Holt, Dennis Charles, 1981, “Time travel: The time discrepancy paradox”, Philosophical Investigations , 4: 1–16.

- Horacek, David, 2005, “Time travel in indeterministic worlds”, Monist (Special Issue on Time Travel), 88: 423–36.

- Horwich, Paul, 1975, “On some alleged paradoxes of time travel”, Journal of Philosophy , 72: 432–44.

- –––, 1987, Asymmetries in Time: Problems in the Philosophy of Science , Cambridge MA: MIT Press.