- All articles

- Women’s History

- Archaeology

- Britain’s best places

Six places to find Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Set 2

by Kate McNab, 6-04-17 Post

Celebrated English author Virginia Woolf was a crucial member at the heart of the Bloomsbury Set, who spun their tangled webs over the south east of England.

Here is our selection of the best places to visit to get a glimpse into the inner workings of woolf and this infamous, and influential, group., monk’s house , rodmell, east sussex.

Virginia Woolf’s bedroom at Monk’s House, Rodmell. © Kate McNab

A must-see property for any Woolf or Bloomsbury fan, it was at Monk’s House, in a small studio set in the garden’s beautiful orchard, that Woolf wrote many of her celebrated novels. Set in an idyllic cottage garden full to the brim with flowers, bushes and trees the 17th Century cottage appears just as it did when the Woolfs inhabited it. The house boasts painted interiors by Virginia’s sister Vanesa Bell, and friend Duncan Grant, and heaps of books – including a set of Shakespeare bound by Virginia herself.

The Woolfs bought the house, in the quiet village of Rodmell, in 1919 as a holiday home, admiring its wild and fertile garden. It became a popular meeting place for the Bloomsbury Group and their friends, who would gather in the garden to relax or play bowls. The pair moved permanently to the property in 1940 after their London home suffered damage during the war, and both stayed here for the rest of their lives.

Virginia Woolf lived here until her suicide in 1941 in the nearby River Ouse. Her cremated remains, and those of Leonard when he passed in 1969, were scattered underneath a couple of elm trees nicknamed ‘Leonard and Virginia’ by the pair. Today, busts of the couple sit atop a wall where the elms once stood.

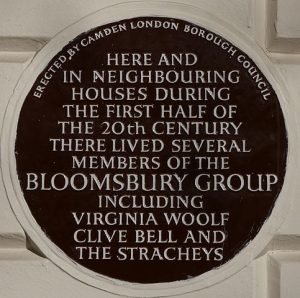

Bloomsbury, London

A blue plaque in Gordon Square. Several members of the Bloomsbury Group lived here in the first half of the 20th century. ‘Blue Plaque, Gordon Square, London WC1’ © Christine Matthews CC BY-SA 2.0

Where it all began. The Bloomsbury area of London is where the eponymous group first formed around the start of the 20th century. Many central male members of the Bloomsbury Group were students together in Cambridge, and congregated in London at the home of Thoby Stephen – Virginia Woolf’s brother. It was here that the likes of Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Roger Fry, John Maynard Keyes and Leonard Woolf grew to know Virginia and Vanessa.

Gordon Square and Fitzroy Square are particular hotspots, having played home to many of the Bloomsbury Group, as well as the Omega Workshop – a Roger Fry, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell’s Omega Workshop, which sought to blur the line between fine and decorative arts and give the artists of the Bloomsbury Group the platform to sell their work, and produced luxury homewares and clothing for the elite.

As well as plaque-spotting the Bloomsbury are has so much to offer for any history, heritage or art fan – a plethora of amazing museums and galleries, historical churches and beautiful architecture.

Dimbola Lodge , Freshwater Bay, Isle of Wight

Dimbola Lodge © Dimbola Museum and Galleries

Dimbola Lodge, in Freshwater Bay is the former home of Woolf’s Great Aunt; the pioneering Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, whose striking Pre-Raphaelite style portraits quite often featured Woolf’s mother Julia Prinsep Duckworth, a prominent Pre-Raphaelite model.

Much like her great-niece, Cameron was at the heart of a community of artists, writers and thinkers, dubbed ‘The Freshwater Circle’ and included the likes of Alfred Lord Tennyson, Lewis Carol and G.F Watts. It was at Dimbola Lodge that Julia Duckworth met Woolf’s father – the English writer, historian and mountaineer Leslie Stephen.

The former residence is now a historic house museum, celebrating the life and work of Julia Margaret Cameron, and is a must-see location for any early photography, or Pre-Raphaelite fan.

Charleston Farmhouse , Firle, East Sussex

Duncan Grant’s studio at Charleston © The Charleston Trust

The home of Bloomsbury artists Duncan Grant and Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell, as well as Clive Bell and John Maynard Keynes, Charleston Farmhouse sits just a stone’s throw away from Monk’s House, in the small Sussex village of Firle.

Purchased by the pair in 1916, the farmhouse was not just their home, but their canvas too – the surfaces, furniture and homewares covered in Bell and Grant’s distinctive designs.

Once a hive of activity where Bloomsbury artists and writers would come together to work, play and socialise, the house remains busy as thousands of visitors visit yearly to take in the brightly painted interiors and amble around the vivid walled garden planted by the duo, full of their favourite flowers and Quentin Bell’s sculptures.

The Church of St Michael and All Angels, Berwick, East Sussex

The interior of St Michael’s and All Angels, Berwick. © Kate McNab

Not far from Charleston sits this truly hidden gem. The Church of St Michael and All Angels in Berwick features a stunning interior, full of murals painted by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, and Vanessa’s children Quentin and Angelica.

During the war, many of the church’s decorative stained glass windows were damaged and, rather than replacing the fragile glass, the Bishop of Chichester commissioned the pair to cover the walls with pastoral scenes. The windows were replaced with clear glass to illuminate the murals within, and offer splendid views over the church yard and South Downs.

The murals remain today and can be visited by anyone when the church is not running a service.

Sissinghurst Castle Garden , near Cranbrook, Kent

Statue of Dionysus in the Nuttery in spring at Sissinghurst Castle Garden, near Cranbrook, Kent. © National Trust Images/Jonathan Buckley

Home to Woolf’s friend, lover and muse Vita Sackville-West, Sissinghurst Castle stands in the grounds of one of the finest gardens in England. Inspiration for Woolf’s revolutionary ‘Orlando’, described by Vita’s son Nigel Nicholson as ‘the longest and most charming love letter in literature’, Vita became infatuated with Virginia after meeting her at a party in 1922. This initial infatuation slowly grew into a decade-long love affair between the two authors.

Vita, who was a garden writer for the Observer, and her husband, the author and politician Harold Nicholson, created the perfectly-manicured garden in the 1930s and it became unintentionally famous through Vita’s writing. The garden was innovative for its time, flowing like a set of interconnected rooms with different themes, and wonderfully showcases Vita’s gardening talents.

Today the Grade I listed garden, as well as its farm and buildings, are owned by the National Trust and thousands of visitors flock here yearly to explore the glorious garden ‘rooms’ and impeccable planting.

popular on Museum Crush

Post The Yorkshire obsession with Ancient Egyptian architecture The Yorkshire obsession with Ancient Egyptian architecture The Yorkshire obsession with Ancient Egyptian architecture

Post The beauty and danger in Victorian Glass Fire Grenades The beauty and danger in Victorian Glass Fire Grenades The beauty and danger in Victorian Glass Fire Grenades

Post Mods, Rockers, Skinheads, Punks: Snapshots of Southend’s Subcultural History Mods, Rockers, Skinheads, Punks: Snapshots of Southend’s Subc... Mods, Rockers, Skinheads, Punks: Snapshots of Southend’s Subcultural History

Post 11 relics of medieval England at Rievaulx Abbey 11 relics of medieval England at Rievaulx Abbey 11 relics of medieval England at Rievaulx Abbey

2 comments on “ Six places to find Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Set ”

Are there any tours to these sites?

Yes, all amazing places! I wouldn’t call Sissinghurst ‘perfectly manicured’ though – that conjures up something perhaps almost suburban and sterile – there is wildness and great beauty at Sissinghurst – at it’s height, the garden spills outs its cornucopia of flowers and trees with a Bacchanalian disregard for order, which I love. Other areas in the garden, are, admittedly, created with greater regard for form and Apollonian effect.

Add your comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Add your comments below:

your name *

Your Email *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Virginia Woolf–Inspired Tour of England

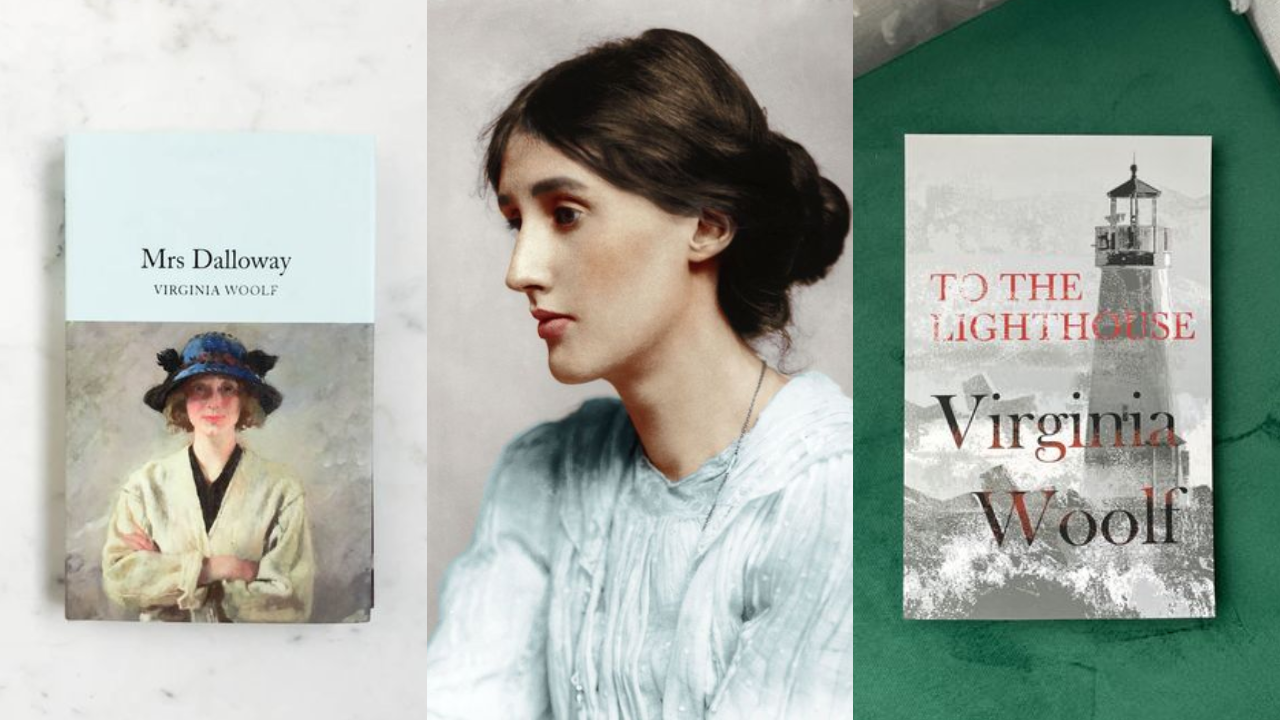

Earlier this month, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced the theme of its 2020 Met Gala and corresponding exhibition: “About Time: Fashion and Duration.” Virginia Woolf will be the “ghost narrator” of the exhibit, which will include quotes from three of her novels, Orlando: A Biography, Mrs. Dalloway, and To the Lighthouse, all of which relate to time. (The 1992 film adaptation of Orlando, which stars Tilda Swinton as the title character, also serves as inspiration.)

Fashion enthusiasts must wait until the first Monday in May to see how celebrities interpret the theme on the Met Gala red carpet, and until May 7 to see the full scope of the exhibit on display at the museum. But for now, there are quite a few properties in Woolf's native England that have a deep connection to the legendary writer, and are worth adding to your U.K. travel itinerary if you are a fan of her work. Her childhood home (located around the corner from Royal Albert Hall); the Georgian-style residence where she and her husband, Leonard Woolf, founded their publishing company, Hogarth Press; and the Fitzroy Square dwelling where she briefly lived with her brother Adrian Stephen are all still private residences today, each marked with one of London's signature blue plaques signifying the connection to Woolf. Other places where she spent time, however, do open their doors to tourists. Read on for Architectural Digest 's list of four.

The writing of Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) is part of the inspiration for the 2020 Met Gala theme.

Sissinghurst Castle Garden

The Elizabethan tower at Sissinghurst Castle Garden in Kent, England.

The formal gardens at Sissinghurst.

This was the home of Woolf's friend and lover, Vita Sackville-West, who inspired the main character in Orlando: A Biography and was a writer and poet herself. Sackville-West and her husband, Harold Nicolson, purchased the property in 1930 and designed its elaborate gardens. Sissinghurst features multiple Tudor-style brick structures—known as West Range, the Tower, Priest's House, and South Cottage. Today, it belongs to the National Trust and welcomes around 200,000 visitors per year.

Monk's House

The interior of Monk's House, which is located in Rodmell, East Sussex, England.

One former home of Woolf and her husband, called Monk’s House, is now a house museum. The Woolfs purchased the 16th-century clapboard cottage in 1919, and entertained guests, including T.S. Eliot, there. The property also includes a garden, a greenhouse, and a writing lodge, where Woolf penned novels, letters, articles, and diary entries. In the more than 20 years that she lived at Monk’s House, Woolf made improvements throughout the home, such as implementing hot water and a toilet, adding two more stories, and purchasing the adjacent field, which became the garden. Inside, there are walls painted by Woolf and hand-initialed tiles surrounding her bedroom fireplace, inscribed with her and her sister’s initials, VW and VB.

Charleston Farmhouse

The exterior of Charleston Farmhouse, which is located in the village of Firle near Lewes, East Sussex, England.

This art gallery, house, and garden was once owned by Woolf's sister, artist Vanessa Bell , and fellow artist Duncan Grant. On the walls of the ivy-covered farmhouse is the artwork of Delacroix, Renoir, and Picasso, to name a few. In 2017, Salvador Dali's Mae West Lips Sofa was on view in the gallery. One of the gallery’s current exhibitions, Coming Home: Virginia Woolf by Vanessa Bell, features a portrait of Woolf by her sister, and will be on display until January 19th, 2020. The garden boasts mosaic sidewalks, a plethora of colorful flowers and lush green bushes and trees, and limestone busts and statues reminiscent of Greco-Roman art.

Dimbola Lodge

Dimbola Lodge was restored in the 1990s.

An intricately carved mantel at Dimbola Lodge.

Woolf’s great-aunt, photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, lived at Dimbola Lodge from 1860 until 1875. Made up of two adjacent cottages that were joined together into a Gothic style, today the property is the Dimbola Museum and Galleries. Much of Cameron’s work is on view, and there are also rotating exhibitions featuring the work of contemporary photographers. This property is located on the Isle of Wight, home to the famous annual music festival.

- No products in the cart.

04 Dec Virginia Woolf’s Bloomsbury and Sussex

“If you do not tell the truth about yourself, you cannot tell it about other people.” – Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf Basics

Virginia Woolf was undoubtedly one of the most important English writers of the 20 th Century. In a BBC poll of 82 non-British critics, two of Woolf’s novels – Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927) – were ranked in the top three English novels of all time. (The third was George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871-72).) Other popular novels by Virginia Woolf include Orlando (1928) – inspired by her relationship with Vita Sackville-West – and The Waves (1931).

Together with her husband Leonard Woolf (they married in 1917) and her artist sister Vanessa Bell , Virginia was a founder member of the Bloomsbury Group of intellectuals, writers and artists, which included EM Forster and John Maynard Keynes. Although she was born in South Kensington in 1882, the family moved to a house in Bloomsbury (46 Gordon Square) in 1904 and Virginia lived there until 1907. She continued to live in and around Bloomsbury until 1914.

After being home-schooled as a child, Virginia went to King’s College, London (a short distance from her future Bloomsbury home) where she studied classics and history. She began writing professionally when she was only 18 years old and she soon developed her trademark “stream of consciousness” style. It’s probable that her many mental breakdowns – she made multiple suicide attempts and was institutionalized several times – had an effect on her work.

Exploring Bloomsbury

Virginia and Leonard moved back to Bloomsbury in 1924, renting a house at 52 Tavistock Square until 1939. They had earlier founded the Hogarth Press and now ran it from the basement, publishing much of Virginia’s output and works by other writers, including TS Eliot’s The Waste Land (1924). There’s a commemorative bust of Virginia in the gardens of Tavistock Square (and at the center of the square is an impressive statue of Mahatma Gandhi).

So Judy and I decided to begin our tour in Bloomsbury. This elegant area of west London is distinguished by the presence of the British Museum and University College, London. We were taken with its cosmopolitan nature, with its bustle of students and tourists. As we strolled along Lambs Conduit Street, passing (and frequently entering) its bookshops and cafes, we easily picked up the area’s distinctly literary feel.

Monk’s House

From London, Judy and I made the 70-mile drive south through lovely countryside and over the South Downs to the village of Rodmell near Lewes in Sussex. It was here that we found Monk’s House (below left), which was purchased by the Woolfs in 1919 and became their permanent home from 1940, when they chose to leave London at the height of the German Blitz.

The house – actually a cottage dating from the 15 th or 16 th Century – is now owned and managed by the National Trust, who have maintained it just as it was when the Woolfs lived there. It was a quite moving experience to wander through the oak-beamed rooms filled with some of their favorite things. We also enjoyed the large garden, much loved by the Woolfs. It was not far away that, in March 1941, Virginia committed suicide by drowning herself in the River Ouse. Leonard continued to live at Monk’s House until his death in 1969.

A short but circuitous drive from Rodmell brought us to the village of Firle and Charleston (above right) – the country home of Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell, and her husband, Duncan Grant – which served as a popular meeting place for members of the Bloomsbury Group. It was fascinating to tour the house, which is filled with examples of their decorative style and reflects the couple’s more than sixty years of artistic creativity.

From Firle we drove one hour north to Knole (above left, near Sevenoaks in Kent). This was the birthplace and early childhood home of the poet and novelist Vita Sackville-West (above right), with whom Virginia enjoyed a close friendship from 1922 until her death. Now owned by the National Trust, Knole is a massive country house, four acres in size, that dates back to the mid-15 th Century (with additions in the 16 th Century and 17 th Century). The surrounding 1,000-acre deer park dates from around 1600. There was so much to marvel at: grand courtyards, great art, fine furniture, and panoramic views from the Gatehouse Tower!

Postscript: Woolf on Screen

Virginia Woolf’s books are notoriously difficult to adapt for the screen. The best might be Mrs Dalloway (1997), starring Vanessa Redgrave, and Orlando (1992), with Tilda Swinton in the title role. Definitely worth viewing is The Hours (2002), starring Nicole Kidman as Viriginia Woolf, which tells how Mrs Dalloway impacts three generations of women. Not so well received was Vita & Virginia (2018) which focused on Virginia’s love affair with Vita Sackville-West.

If you’re thinking of visiting Virginia Woolf’s Sussex, allow a full day to explore Monk’s House and Charleston. Be sure to outfit yourself with comfortable shoes, a light jacket and a feeling for the exotic. Looking for more to do in the area? Consider Arundel Castle – a spectacular and well-preserved 11th Century fortress – and Battle Abbey and Battlefield – site of the 1066 Battle of Hastings, which brought the Norman duke William the Conqueror to the English throne. To visit all of these and other fascinating literary and non-literary sites associated with your favorite writers, plan your itinerary here.

Privacy Overview

Your privacy

We use cookies to help make our site work properly and to analyze how our site is used. You can view our cookies policy , manage your cookie preferences , or consent and dismiss this banner by clicking agree:

- A Guide to Virginia Woolf in Kent and Sussex

By Emma Bouloudis

Channel your inner Mrs Dalloway and trace the feminist-icons footsteps across the countryside

Modernist maven and writer of some of the most sumptuously rich love letters in the English language, Virginia Woolf is an icon of literary proportions. So take a page out of her book and swap the cacophonous rush of city life for the green pastures of the countryside whilst dutifully brandishing a copy of Mrs Dalloway in hand.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Charleston (@charlestontrust) on Mar 4, 2020 at 1:49am PST

Charleston Farmhouse and Garden

A favourited countryside retreat of the outlandishly bohemian Bloomsbury Group, this pastoral little farmhouse is an essential pilgrimage for dedicated poetry-buffs and art-fans alike. As the home of Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell, it soon become clear as you enter that almost every surface in this fantastical cottage has been adorned with fierce brushstrokes, expressive sculptures, and lacquered in vibrant pinks and blues.

You can even lock eyes with the feminist icon herself, there’s a hand-sculpted bust of Virginia created by Stephen Tomlin in the art studio at the rear of the house.

The house and garden are open to visit Wednesday to Sunday and adult admission starts at £11

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Monks House NT (@monkshousent) on Oct 11, 2019 at 7:27am PDT

Monks House

Visit Virginia’s very own ‘room of one’s own’ and head to her weathered writing shed crouched in the gardens of Monk’s House, the 16th century cottage she bought with her husband, Leonard. With the garden erupting in spatterings of multicoloured blossom and rosy apple trees, it’s easy to imagine Woolf frantically jotting down inspiration come rain or shine, you can almost smell the typewriter ink and cigarette smoke.

Make sure to ferret out the tiled fireplace in her bedroom where you’ll find a hand-painted panel of a lighthouse guiding a wave-beaten sailing ship, emulating the scene from one of the author’s most celebrated novels ‘To the Lighthouse’.

Monk’s House is a National Trust property, adult admission is priced at £6.60 and available to buy at the entrance

View this post on Instagram A post shared by South Downs National Park (@southdownsnp) on Feb 8, 2020 at 10:00pm PST

Explore the village of Firle

After a day of hiking the blustery seascape of the Sussex Downs, Virginia preferred nothing more than to retire to Little Talland House, her marital home in the picturesque village of Firle. Although you unfortunately can’t visit Talland yourself, Firle is charming to explore in its own right and perched on the undulating vistas of the South Downs there’s no better place for a dramatic afternoon wander along the salty stretches between Birling Gap and Cuckmere Haven.

Post-ramble drop into the Ram Inn, a well-loved haunt of the Bloomsbury pack, we suggest opting for a golden pint of ‘Sussex Best’ courtesy of local institution Harveys.

Walking trails and digital route guides around Firle and the rest of the South Downs National Park are available to download from their website here

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Sissinghurst Castle Garden NT (@sissinghurstcastlegardennt) on Jan 13, 2020 at 8:27am PST

Sissinghurst Castle Garden

Sissinghurst is totally stunning to behold, ubiquitous for its acres of manicured lawns it’s nothing short of world-famous for its prim and paridisal 20th century gardens. However, lesser known is that its former bluestocking custodian Vita Sackville-West, was a lover and friend of Virginia’s and inspired her gender switching protagonist in the author’s feminist-fuelled masterpiece Orlando .

Peppered throughout the castle, eagle-eyed guests will find a wooden-framed photograph of Virginia perched on the desk on the desk of Vita’s writing room as well as a ‘Hogarth Press’ gifted to Vita and her husband by Virginia and Leonard.

Sissinghurst is open all year round with adult admission starting at £10.40

- Share full article

In Search of Virginia Woolf’s Lost Eden in Cornwall

The vast coastal county of Cornwall, England, had a profound effect on the future writing of the impressionable young girl who would become a literary star.

Godrevy Island and lighthouse in St. Ives Bay. Credit... Andy Haslam for The New York Times

Supported by

By Ratha Tep

- Feb. 26, 2018

Virginia Woolf wasn’t always the radical we imagine today. Before the debates on truth and beauty with her circle of early 20th-century artists, intellectuals and writers known as the Bloomsbury Group; before the polemic feminist lectures at Cambridge; and before the ever-constant push to experiment with new forms of fiction, there was the impressionable young girl, born Adeline Virginia Stephen, who spent seaside summers in Cornwall, on England’s rugged southwestern tip.

On a gray morning last October, I found myself on the Great Western Railway, rolling along the same route that Woolf would have taken about a century before, the train hugging tight past a progression of wide swathes of golden sand and languidly sloping green cliffs, with the deep blue of St. Ives Bay and the Godrevy Lighthouse in the distance.

The rail line to the coastal town of St. Ives opened in 1877, causing a huge uptick in tourism there, and it is easy to understand how it would have lured well-to-do Britons like her family to this once hard-to-reach stretch of Cornwall, now a thriving arts haven with its own branch of the Tate museum.

Long an admirer of this modernist literary pioneer, not only for how Woolf redefined the possibilities of the novel but, for the simple reason that no other writer has given me, sentence for sentence, such pleasure, I decided to go in search of Woolf in her early years. I headed to the vast coastal county that, by most accounts, had a profound effect on her future writing, making its way into the novels “Jacob’s Room” and “The Waves,” and forming the basis of one of her greatest works, “To the Lighthouse.”

Woolf’s summers in Cornwall were a reprieve from her upper-middle-class life in London, where, for most of the year, she spent her days in “the rich red gloom” of a tall London townhouse. A Victorian girl bound by Victorian-era trappings, she took informal school lessons in a dining room filled with carved oak and marble, ventured on monotonous twice-daily outings to nearby Kensington Gardens, and awaited a future of ballroom dances in satin dresses and pearls.

Her father, the renowned literary critic and historian, Sir Leslie Stephen , rented a house overlooking St. Ives Bay in Cornwall, which he described in an 1884 letter as “a pocket-paradise with a sheltered cove of sand in easy reach (for ‘Ginia even) just below.” That house, that bay, that lighthouse: all would be immortalized in her famous novel. While Woolf was always careful to abstract somewhat from her personal past, and set “To the Lighthouse” on the Scottish Isle of Skye, it’s steeped with almost direct imagery from her time in Cornwall.

From 1882, when she was only a few months old, to 1894, when she was 12, the year before her mother died, Woolf spent a few months each year in Talland House , situated on the outskirts of St. Ives, then a small fishing town on the Cornish coast.

It was the sheer physical freedom of Cornwall, compared to the constrictions of Woolf’s London life, suggest the scholars Marion Dell and Marion Whybrow in “ Virginia Woolf & Vanessa Bell: Remembering St. Ives ,” that helped her buck against the constructs of her day and conceive of independent achievement.

Woolf roamed free in the salty air of the sloping garden, with the expanse of the bay and its distant lighthouse before her. She swam and poked among rock pools down at the beach below, and hunted great-winged moths on rambling nighttime expeditions.

“In retrospect nothing that we had as children made as much difference, was quite so important to us, as our summer in Cornwall. The country was intensified, after the months in London,” and formed “the best beginning to life conceivable,” she wrote in 1940 at age 58, in her autobiographical essay, “A Sketch of the Past.”

Celebrating St. Ives’s outsized role in Woolf’s life, and a marker in its own right for how far the town has grown, is the recently refurbished and extended Tate St. Ives , one of only two branches of the art museum outside London, which runs “Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Writings” until April 29 in its sprawling new hall.

But while St. Ives has dramatically evolved from Woolf’s day, some parts of Cornwall, a sprawling county with a population of over half a million, seem frozen in time. Just down the coast, I found a rural, stark, ethereally beautiful landscape that remains today, despite the occasional car and hurtling tractor, close to how Woolf would have remembered it as a child.

Once a 10-hour trek from London, the train voyage to St. Ives today can be made in under six. Winding my way up from the town’s sole rail station, as Woolf and her family would have done — with cooks, servants and mounds of luggage — the mid-19th-century stone villa looms large, seemingly incongruous among the motley assortment of architecture that has sprung around it, like the glossy modern apartment complex, with glass balconies, next door.

“Her family would move their entire way of life, their whole household, for two or three months out of the year to this house with a magical garden in this very remote setting, and it would become a kind of Eden for her, the place she would idealize and always remember,” said Alexandra Harris , author of “ Virginia Woolf ” and a professorial fellow at the University of Birmingham in England.

“In ‘To the Lighthouse,’ Woolf, as a successful middle-aged writer, comes face to face with her mother in the garden which is very much the garden at Talland House,” Ms. Harris said. “The novel embodies the feeling of having left something unfinished through those childhood summers.”

“To the Lighthouse” encapsulates Woolf’s love and longing for her mother — as well as her conflicted view of her mother’s vision of Victorian womanhood. All those bottled-up feelings, seemingly suspended in time after the family gave up Talland House following Julia Stephen’s death, found their release in the novel.

Woolf herself wrote as much in “A Sketch of the Past:” “ … when it was written, I ceased to be obsessed by my mother. I no longer hear her voice; I do not see her.”

While Talland House was carved into five flats in the 1950s and isn’t open to the public, visitors can, from Talland Road above, catch a glimpse of the sloping garden, the house’s cream-colored facade and views across St. Ives Bay to the iconic Godrevy Lighthouse. Though for the best tableau, it’s best to mimic the writer and her three siblings on their first trip back to the house as adults.

“We passed through the gate, groped stealthily but with sure feet up the carriage drive, mounted the little flight of rough steps,” wrote Woolf in a 1905 diary entry, adding that they peered through a chink in the escallonia hedge and “hung there like ghosts.”

The original wooden gate no longer exists, though the “rough steps” and hedging, now about chest-height, are still there, beyond which is a full-on view of the house and its stately French windows and balconies. Visitors can also walk up the paved driveway, the former “carriage drive,” around the side of the garden, said Peter Eddy, the house’s longtime owner (with his brother, John Eddy), who met me there.

I found Mr. Eddy with a few of the house’s current residents, Woolf enthusiasts who are also deeply embedded in the town’s fabric (one is the chairman of the St. Ives Chamber of Trade and Commerce, another a volunteer at the St. Ives Archive). Ad hoc gatekeepers of the Talland House myth, they were poring over a map of the property from 1906 and historical photos, which showed a smaller and less imposing house. (Roof and side extensions were added later.)

I walked around, soaking up the spirit of the place.

The garden is more manicured now, lacking the bursts of color from fiery red-hot pokers, and various pockets of charm, which were given names like the “love corner,” “coffee garden” and “lookout place,” that had defined the original garden. Yet a few relics remain, including feathery spears of pampas grass near where Woolf would have played evening games of cricket, and mixed hedging around the garden’s bottom border that included Woolf’s beloved escallonia, “whose leaves, pressed, gave out a very sweet smell.”

Looking across St. Ives Bay from the garden, I recalled one of the best-known lines from “To the Lighthouse:” “For the great plateful of blue water was before her; the hoary Lighthouse, distant, austere, in the midst …”

Woolf fans have been concerned about the obstruction of this view ever since Cornwall Council granted planning permission in December 2015 for an apartment complex to be built below Talland House. But on my visit, it was not clear to me this would happen. I couldn’t find any signs of construction, and permission is set to expire if work doesn’t start by December 2018.

Just minutes’ walk away is Primrose Valley, an area once blanketed with apple orchards and a little dirt path that Woolf and her youthful siblings would have taken down to Porthminster Beach below. Now, sprawling houses with gray-shingled mansard roofs edge up to one another, with hedging and moss-covered stone lining a paved route. The beach, though, with its wide crescent of smooth, powdery sand and turquoise bay, still retains its essential, sweeping majesty.

From the beach, it was a few blocks to the center of St. Ives. I walked past a girl with a butterfly net, and thought of Woolf, and got lost among the labyrinth of cobbled streets. But I couldn’t find much left of the “windy, noisy, fishy, vociferous, narrow-streeted town” as Woolf recalled it. Long gone are the wooden boats that would have been anchored near the shore, awaiting the pilchards — small, sardine-like fish that would come into the bay by the millions. All that has largely been scrubbed clean, replaced with a more tourist-friendly image: St. Ives, the arts haven by the sea.

Woolf was witness to the beginning of this change. In “To the Lighthouse,” she noted that the artists had already started to come to the fictional fishing town inspired by St. Ives, perhaps a reference to the American painter Whistler, who stayed in St. Ives in 1883 and 1884 . In the early- to mid-20th century, a new wave of artists made their way there, most notably Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo, whose abstract sculptures and paintings were inspired by the area’s landscape.

For the first time, these modernist works have a permanent dedicated space in the Tate St. Ives, which has a vast new extension dug into a hillside off Porthmeor Beach, a favored spot with surfers that doubled the museum’s gallery area in October.

While traces of Woolf’s work were noticeably absent at the museum in autumn, “Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Writings,” showcases the works of more than 80 artists, including her sister, the painter and Bloomsbury Group member Vanessa Bell, who have either been directly influenced by Woolf or explore recurring themes important to Woolf, such as feminist perspectives on domesticity.

Bell, one of Woolf’s greatest confidantes, received a rather alarming letter, written on Christmas Day, 1909. “I went for a walk in Regents Park yesterday morning, and it suddenly struck me how absurd it was to stay in London, with Cornwall going on all the time,” Woolf wrote. Woolf impulsively purchased a train ticket and arrived at the Lelant station, near St. Ives, at 10:30 p.m., without “spectacles, cheque book, looking glass, or coat.” Pacing that same platform recently, I was struck by how Woolf might have chosen her lodging: The Lelant Hotel, now The Badger Inn , was the closest accommodation, looming large up a short, steep walk to the top of Station Hill.

There, I met Paul O’Brien, the pub’s historian, who has put together snippets of Woolf’s letters about Lelant, a village of 1,056 residents, in a frame that hangs on a wall near the bar. It was a Tuesday afternoon, and convivial locals were drinking pints of St. Austell’s Tribute, a popular regional ale, their dogs underfoot.

From The Badger Inn, it’s about seven miles to Godrevy, a beach and headland that is now part of the National Trust . There, sunlight streamed down through the clouds and seemed to reflect the golden sands, lighting up the whole place in the area’s infamously soft glow. I walked past wild flowing grasses before reaching the closest point on shore to Godrevy Island and its lighthouse. And then the literary landmark stood before me: stark, solid, sacrosanct.

Woolf’s next trip to Cornwall was more scripted. Back in London and nearing, at age 28, the end of her first novel, “The Voyage Out,” Woolf spiraled into a mental breakdown so severe it landed her in Burley Park, a home for mentally ill women outside the city. (While Hermione Lee , arguably the foremost Woolf expert, called her “a sane woman who had an illness” in her biography “Virginia Woolf,” she also associated Woolf’s symptoms with what would now be recognized as manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder.)

Part of her recuperation that summer was a walking tour around Zennor, the name of both a tiny village and parish (population 207), just southwest of St. Ives, with a nurse, Jean Thomas.

Tramping through a light mist, I found my way to the handsome stone farmhouse where Woolf and Ms. Thomas stayed, now the private residence of Lee and William Berryman, whose family has lived and worked on the surrounding farmland for more than 400 years. Inside their cozy sitting room, Ms. Berryman and I pored over small sepia-colored photographs, some nearly a century old, of former lodgers. (My heart leapt when I found one of two women sharing a motorcycle and sidecar, though, while possessing the same independent spirit, it ended up not being Woolf and her nurse.)

Then we ventured outside, touring two nearby structures that have been turned into holiday accommodations, called Porthmeor Cottages . Chickens pecked outside a coop, and in the distance, cattle grazed open pastureland that seemed to drop off into the sea below.

Three years later, in 1913, a similar pattern of illness emerged. Woolf sank into periods of severe depression, and was again admitted to Burley Park. In September, Woolf attempted suicide. After a period of rest, she slowly improved, and with her husband in 1914, headed again to Cornwall.

They spent a portion of their stay at Carbis Bay, a seaside resort village about a mile and a half up the coast from St. Ives, that is today dotted with tanned surfers in wet suits on the beach and, looming above, whitewashed, glass-fronted villas.

The Carbis Bay Hotel & Estate , where the Woolfs stayed, has its own beach that was awarded Blue Flag eco-certification, as well as a spa. Its palm-tree-fringed views of the sweeping turquoise bay could have been from anywhere, more Caribbean than Woolf’s Cornwall. Except there, in the distance, was the Godrevy Lighthouse, and in a hallway off a glass conservatory hangs a photo of the couple from around that time, with Woolf’s guest signature in purple, below.

During the 1920s and 1930s, a creatively fruitful time for Woolf, when she worked on the three novels most closely associated with Cornwall, the couple mainly stayed in the parish of Zennor whenever they visited the area.

As I made my way around its medieval farming tracts, sweeping moors and winding coastal paths, I understood why. It was an antidote not just to the frenzy of London, but also to the rapid growth of St. Ives and Carbis Bay.

Off the main road and onto a dirt track sits the tiny hamlet of Poniou, which then, as now, consists of only three cottages beside three granite footbridges. I met Sue Allen, a longtime resident, who told me the Woolfs had stayed next door in 1921, with their bedroom facing the sea.

Woolf marveled at seeing Gurnard’s Head , a glorious headland named for the local fish, from that bedroom window.

Then as now, it remains the most distinctive landmark in the area. But it is still, as Woolf described it, “so lonely,” reachable either along a winding “rabbit path round the cliff,” or by following a faintly visible path through fields dotted with grazing cattle and rudimentary stone steps. Taking in the faintly sweet smell of cow dung and the roar of the waters crashing against the rocks below, I didn’t pass a single soul on two trips in October.

About three miles away is the private residence Eagle’s Nest, distinct and visible from the main road. The Woolfs stayed there with friends on several memorable visits, including on Christmas Day, 1926, which Woolf spent revising drafts of “ To the Lighthouse.” She despaired that “All my facts about Lighthouses are wrong,” in a letter to an assistant at the publishing house, Hogarth Press, which she and her husband set up and ran.

The couple stayed there again in May 1936, Woolf’s last trip, at age 54, to Cornwall, an attempt to keep yet another breakdown at bay. They wandered round St. Ives and crept into the garden of Talland House, and in the dusk, her husband wrote, “Virginia peered through the ground-floor windows to see the ghosts of her childhood.”

I peered through those same windows, and I imagined the writer trying to recapture a vanished past when life had felt so new, seeing only inescapable childhood ghosts basking in summer days of exquisite happiness.

Ratha Tep, based in Dublin, is a frequent contributor to the Travel section.

Advertisement

Pay a visit to Virginia Woolf’s Monk’s House

Lewes, sussex.

Travel back in time to see how the poets, artists, intellectuals and philosophers of the Bloomsbury Group lived.

The rooms of Monk’s House have been preserved with such care, they look as if Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard might return from a countryside stroll at any moment.

See Woolf’s personal collection of Shakespeare’s plays that she handbound, which remain on a bookshelf in her bedroom. Explore the garden, tamed and shaped by her husband, the famous political theorist, editor and writer, Leonard Woolf.

Step back nearly a century and step into Virginia’s famous writing lodge. Take in the views of the orchard that inspired Woolf’s short story and, beyond, of Mount Caburn and the South Downs.

To fully immerse yourself in the atmosphere of early 20th century intellectualism, stay in the studio cottage in Monk’s House garden.

- Find out more about Monk’s House and plan your visit

- Find more literary holidays in Sussex

Refine your search:

You may be interested in...

Go fossil hunting in East Sussex

You never know what you might find on a fossil-hunting session on Peacehaven beach.

Location: East Sussex

Be a real knight or princess for the day at Bodiam Castle

Take a glimpse of medieval splendour where brooding walls rise majestically from a moat, and let the magic of Bodiam Castle capture your imagination.

Location: Robertsbridge, East Sussex

Enjoy a romantic date beneath a canopy of stars and dark sky

Escape the bright lights of the city with a romantic, intimate break in Sussex’s coastal countryside – just you, your date and billions of stars.

Location: Eastbourne, East Sussex

Soar above England’s highest chalk sea cliff

Work up the courage for a unique, exhilarating way to take in the iconic scenery of East Sussex’s famous Beachy Head, near Eastbourne.

We've something we want to share

Want to receive travel tips and ideas by email?

VisitEngland would like to invite you to take part in a short survey about our website, it should take no more than a couple of minutes.

Go to the survey

To add items to favourites …

… you need to be logged in.

If you already have an account, log in.

Or register a new account

Access your account

Advertisement

Where virginia woolf listened to the waves, arts & culture.

The art and life of Mark di Suvero

Virginia Woolf’s Talland House

When she was in her late fifties, Virginia Woolf wrote that her most important memory was of lying in bed at Talland House—the nineteenth-century home in St Ives, Cornwall where she, her parents, and her seven siblings spent every summer until she was thirteen—and listening to waves break on the beach as sunlight pressed against a yellow blind. It was “of lying and hearing this splash and seeing this light, and feeling, it is almost impossible that I should be here; of feeling the purest ecstasy I can conceive.” This radiance and cresting water would be consecrated again and again in her writing, saturating not only essays, diaries, and letters but also Jacob’s Room , The Waves , and To the Lighthouse . As Hermione Lee notes in her biography of Woolf, “Happiness is always measured for her against the memory of being a child in that house.”

When Woolf’s mother died of rheumatic fever in 1895, the Stephen family’s visits to Talland House abruptly ceased. Its lease was sold soon afterward. Some thirty years later, this sudden, devastating break—the actual and figurative end to Woolf’s childhood—would spark the plot of To the Lighthouse , her novel about a family of ten who spends the summer in a remote seaside town. The family’s house, and its surroundings, are as vital to the book as its cast of human characters; I went to St Ives to see what they might teach me, not just about Virginia Woolf but also about those homes by which we measure happiness.

It was a clear June afternoon when I boarded the train, sipping wine, skimming past apricot bluffs; I was feeling as dreamy as Woolf about the journey. “This time tomorrow,” she wrote in 1921, “we shall be stepping onto the platform at Penzance, sniffing the air, looking for our trap, & then—Good God!—driving off across the moors to Zennor—Why am I so incredibly & incurably romantic about Cornwall?” Four hours later, St Ives Bay at last unveiled itself, the same view, more or less, that causes Mrs. Ramsay—Woolf’s mother’s analogue—to stop short, exclaiming at “the great plateful of blue water,” with its “hoary Lighthouse” and “green sand dunes with the wild flowing grasses on them.” I’d read those words a hundred times, and the image they had always conjured was of a seascape much nearer and brighter than this one, but I liked this readjustment of my vision. It was an enlargement, the gentle pop of a jigsaw puzzle fitting together, and so, too, after dinner, when the cobblestone path curved around and up to reveal a vast sandy beach, the waves coiling and crashing in rows of four. I understood then what Woolf meant when she wrote, addressing Cornwall’s pull, of “old waves that have been breaking precisely so these thousand years,” and when she wrote, in her original notes for To the Lighthouse , that “the sea is to be heard all through it.” As much as anywhere I’ve ever been, the sea is the lifeblood of St Ives.

The following morning I woke early and wandered into town, a heap of shops and houses, nestled around a harbor, whose turquoise waters and spiky palms gave it an unexpectedly Mediterranean feel. This wasn’t my first literary pilgrimage, but I was still surprised by the faintness of Woolf’s footprint; the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, whose nearby studio and garden were on view, had handed down a far more potent legacy. It wasn’t until I approached one of the tour guides on the wharf hawking expeditions that my pursuit was in some sense rewarded. “We aren’t going to the lighthouse today,” he told me. “There isn’t enough interest.” His competitor said the same, adding that the tides would make the trip unfeasible for some days’ time, but she also handed me a crumpled printout: Godrevy Lighthouse “inspired Virginia Wolf [ sic ] to write the book The Light House ,” it declared with confidence, explaining that the author had visited in 1892 and signed a guestbook that would later fetch £10,250 at auction.

That was my only overt brush with Woolf that day, but as I continued to explore the town it was easy to see how such a spot might have helped to birth her novel, a narrative rife with angry seas and images of wreckage. The fierce currents that precluded my Godrevy trip—an apt failure, given the Ramsays’ own aborted voyage in the novel—have left deep scars on the community. I consoled myself with a cruise to Seal Island, our boat hugging the crumpled, lime-green cliffs; the guide was a retired lifeboat captain who remembered climbing the rocks as a child and being stranded as the tide rushed in. Later, roaming the cobblestone streets, I chanced upon a large bronze plaque, tarnished and sweetly wordy: IN MEMORY OF THE MEN OF SAINT IVES WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE PURSUIT OF THEIR PROFESSION OF FISHERMAN WHILE WORKING IN VESSELS REGISTERED IN THE PORT OF ST IVES . And when I read up on Godrevy Lighthouse, with the help of a more reputable source, I learned of dozens of additional disasters, among them the 1649 wreck of the Garland, a ship carrying the possessions of newly beheaded King Charles I and his fugitive queen. Of the sixty or so passengers, a man, a boy, and a wolf-dog were the sole survivors; for years afterward, it was said, gold buttons washed up on the beach at Hayle.

Is it any wonder, given this fearsome history, that Woolf’s characters in To the Lighthouse , grappling with their own catastrophic loss, embraced a language of nautical apocalypse? Cam, the Ramsays’ youngest daughter, has a fantasy of being “in a great storm after a shipwreck,” Mr. Ramsay finds comfort in recitation of William Cowper’s “The Castaway,” and Macalister is haunted by the memory of seeing three sailors clawing at the mast as he watched their ship go down. In Virginia Woolf’s Cornwall, it is the ocean’s fury—not its beguiling beauty, not the ecstasy it kindles—that is at the heart of things.

Talland House sits on a hill to the east of St Ives Harbour. When, at the end of a cul-de-sac, it finally materialized, I felt a stab of disappointment. Its ivory walls were streaked with rust, and a tangle of exterior metal staircases crept up the rear. A Ford Focus was parked in the driveway. I was still debating my approach when a beefy young man in blue sweatpants walked out with a Rottweiler. “Yeah?” he asked, suspicious.

“I’m just looking at the house,” I said. “You know Virginia Woolf lived here?”

“Is it okay if I look around?”

“Yeah,” he said again, gesturing toward a snarl of vegetation. “There’s a lawn round back if you like.”

I thanked him, wondering how many seekers had appeared at his door, then plunged into the upper garden. Much of the land had been sold off, and a parking lot replaced the orchard, but I could still see what Leslie Stephen, Woolf’s father, had meant by “a garden of an acre or two all up and down hill, with quaint little terraces divided by hedges of escallonia.” A stepping-stone path led off to the left. I followed it down into a clearing with a tiny pond, hidden from the house above. Then, treading onto the main lawn, I finally met the Talland House I knew from pictures. The ivy had been stripped from its façade, and its railing replaced by an addition, but I recognized the two sets of French doors that opened onto steps—there’s a photograph of Henry James perched here, reading—and, above them, the wrought iron verandahs that appear in one of Woolf’s earliest memories: her mother emerging “onto her balcony in a white dressing gown” as passion flowers spilled from the walls. I was peering through the French doors into the drawing room when I heard the gardener, crossing the lawn with a stack of severed branches in his arms.

He was in his early forties, friendly, weathered, with strawberry blond hair. “I could show you some pictures if you’re interested,” he said, when I explained why I was there.

“Oh, yes!” I said. He raised his bundle of branches, and told me he would bring the photographs on his return.

In his absence, I looked through windows. One revealed a generous foyer, another a bedroom with a collection of dead-eyed antique teddy bears. The door to the apartments upstairs was open, and I climbed the narrow stairs toward the attic, which in To the Lighthouse “the sun poured into,” drawing from “the long frilled strips of seaweed pinned to the wall a smell of salt and weeds, which was in the towels too, gritty with sand from bathing.” I had always loved that porous image, and in fact all descriptions of the Ramsays’ home suggest a space as bleached and weathered as a rowboat, a space that maintains only the flimsiest barrier between the family and the elements—an encroachment by nature that prefigures “Time Passes,” the novel’s anarchic middle section. But the attic that day was dark and dry, with clean blue carpets and bolted doors that precluded further exploration; even the rooms facing the bay seemed unusually hermetic, as if they hailed from an altogether different book.

The gardener came back covered in blood. “I cut myself looking for the pictures,” he said apologetically, holding up three large black-and-white photographs, or rather, photocopies of photographs, encased in rickety frames, ribboned with cobwebs, and now slightly smeared with red. He assured me he was all right and turned the frames around to reveal their written descriptions. “Family by front door c. 1892,” read one, and another, “Adrian, Thoby, Vanessa, Virginia with dog.” I was struck by Woolf’s fidgety hands, by the girls’ heavy skirts, by the obvious intimacy between sisters. “You’re welcome to them,” he said, “if you can get them back to America.” Looking closer, I saw that spiders had attached their egg sacs to the glass, but I accepted the photos gratefully and held out my hand to say goodbye. The gardener hesitated: “I’m a bit bloody, I’m afraid.” We shook with his left instead.

Before leaving, I paused and looked one last time at the house. Time passes, I thought, yes, but what does that mean? To the shock and despair of all who have read To the Lighthouse —if you haven’t, consider this your spoiler alert—Mrs. Ramsay dies unexpectedly midway through the novel; with her gone, the Scottish property is abandoned, its light extinguished. Mrs. McNab, the housekeeper, eventually intervenes to protect against the house’s total collapse, but not before Woolf can offer an alternate rendition of its fate:

In the ruined room, picnickers would have lit their kettles; lovers sought shelter there, lying on the bare boards; and the shepherd stored his dinner on the bricks, and the tramp slept with his coat round him to ward off the cold. Then the roof would have fallen; briars and hemlocks would have blotted out path, step, and window; would have grown, unequally but lustily over the mound, until some trespasser, losing his way, could have told only by a red-hot poker among the nettles, or a scrap of china in the hemlock that here once some one had lived; there had been a house.

Woolf’s vision of the future could just as easily be a vision of the past. The prickly, poisonous foliage restores the land to wilderness; the figures she chooses to populate the scene—lovers, tramps, and shepherds—are eternal. But as I gazed up at Talland House and the nearby flats and cranes (a rising apartment block will soon obstruct Talland’s lighthouse view), I felt a twinge of nostalgia for that more elemental prophecy. I wished for the reabsorption of the home into the earth, so that, for trespassers like me, it would live on only in language. Instead, with its rusty staircases and labyrinthine additions, it seemed some grotesque distortion of itself.

I was halfway down the drive when the gardener ran toward me with a folded piece of paper. “My CV,” he said, “in case you ever need a gardener in the States.” He admitted that after twelve years he was being let go—apparently the landlord had decided that Talland House no longer needed full-time upkeep. I thought of Mrs. Ramsay as she joins her husband on the lawn, lamenting the fifty pounds that it will cost to mend the greenhouse. Even so, she says, the gardener’s beauty is so great that she couldn’t possibly dismiss him.

As I walked down the hill to the beach, it occurred to me that Mrs. Ramsay’s refusal to fire the gardener is yet another way in which she protects her family and home against the ferocity of nature, and that, conversely, the dismissal of Andrew Shaw—the name on the CV—was the first step toward Woolf’s vision of a timeless, sylvan future. Perhaps the garden will grow wild after all.

On my last morning in St Ives, I dove beneath the waves at Porthmeor Beach—dodging the noxious jellyfish that Woolf described as “lamps, with streaming hair”—and then sat dripping on the sand, overcome, not for the first time that trip, by a kind of quiet, spreading contentment. Woolf would retreat to Cornwall again and again over the course of her life, lured by its sea air and seclusion; this spot “on the very toenail” of England, as her father called it, seemed to offer her a sustenance unlike that of anywhere else in the world. “I went for a walk in Regents Park yesterday morning,” she wrote to her sister Vanessa Bell in 1909, explaining an impulsive journey that dropped her at the station in Lelant in the middle of the night, without her glasses or a coat, “and it suddenly struck me how absurd it was to stay in London, with Cornwall going on all the time.” But though she would return to Talland House on several occasions, sneaking across the grass and peeking through its windows, this site of so much early happiness remained forever out of reach. One evening, in 1905, she and her siblings climbed the steps of their childhood home for the first time since their mother’s death. “As we well knew,” she wrote, “we could go no further; if we advanced the spell was broken. The lights were not our lights; the voices were the voices of strangers.”

Katharine Smyth is the author of All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf. A graduate of of Brown University, she has worked for The Paris Review and taught at Columbia University, where she received her M.F.A. in nonfiction. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Adapted from All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf , by Katharine Smyth, published this week by Crown.

Travel Thru History

Historical and cultural travel experiences

Literary London: Virginia Woolf’s Bloomsbury

by Lynn Smith

For those people who have a passion for literature, history and London, a London guided walking tour will combine all these interests. There are several such tours available, led by knowledgeable guides, most of whom have been trained by the London Tourist Board. The tours are also reasonably priced.

I met the tour guide outside Russell Square Underground and we began the two hour walk from there. It was a beautiful summer’s day which allowed us to see the green and pleasant squares at their best.

Bloomsbury is in the Borough of Camden and is bounded on the north by Euston Rd, Gray’s Inn Rd on the east, Tottenham Court Rd on the west and High Holborn on the south side.

The area has a fascinating history. The name Bloomsbury is a corruption of “Blemonde” which was the name of Baron Blemonde, William the Conqueror’s vassal who received the land from William in the 11th century.

In the 19th century, Bloomsbury lost some of its glamour – trade and industry moved in and the area was no longer considered to be fashionable. The British Museum was erected on its present site in 1823 and London University began in 1827.

The arrival of the Bloomsbury Group in the early 20th century gave the area its reputation as an intellectual, artistic and somewhat Bohemian area – a reputation which is still considered relevant today.

Virginia Woolf (born Stephen, 1882 – 1941) was the third child of Sir Leslie Stephen and his wife Julia. Virginia’s siblings were Vanessa, Thoby and Adrian. The family lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate, a large house always filled with children, friends and family.

The Stephen children grew up in a literary household – Sir Leslie was a journalist and had a well-stocked library, to which Virginia had unrestricted access.

When she was thirteen, Virginia’s beloved mother died and this traumatic event caused her first mental breakdown; this was followed by another breakdown when her father died in 1904. After Sir Leslie’s death the Stephen children decided to leave Hyde Park Gate (with its unhappy memories) and move to Gordon Square, in the heart of Bloomsbury, just north of the University of London.

Gordon Square soon became a meeting place for Thoby Stephen’s Cambridge friends. Other visitors were Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and later, Leonard Woolf. Virginia and Vanessa both took part in the lively discussions at these meetings, which could be described as the beginnings of the Bloomsbury Group.

After Thoby’s death from typhoid in 1906 and Vanessa’s marriage to Clive Bell shortly after, Virginia and Adrian left Gordon Square and rented a house at 29 Fitzroy Square.

Fitzroy Square

Although still in the Borough of Camden, Fitzroy Square is not strictly Bloomsbury but Fitzrovia, just further south of Tottenham Court Rd. The area was originally developed to provide houses for the aristocracy and many elegant mansions were erected, designed by Robert Adam. Building began in 1792 and was eventually finished in 1835.

In 1907, when the Stephens moved into 29 Fitzroy Square, the area consisted mainly of offices, workshops and lodging-houses. These unpretentious surroundings suited the brother and sister; they carried on with the Gordon Square intellectual get-togethers and the circle soon grew. An important addition to their gatherings was Lady Ottoline Morrell (1873-1938) – that eccentric and Bohemian patron of the arts, who lived in nearby Bedford Square.

The years at Fitzroy Square were eventful ones for Virginia – her two nephews (Vanessa’s sons) were born in 1908 and 1910 and in 1909 she accepted Lytton Strachey’s proposal of marriage but, by mutual consent, the engagement was cancelled almost immediately.

When the lease of 29 Fitzroy Square came to an end in 1911, Virginia and Adrian leased a four-storey house, No 38 Brunswick Square, which they shared with Maynard Keynes and Duncan Grant. While living in Brunswick Square, Virginia became engaged to Leonard Woolf and they were married on 10 Aug. 1912. The Woolfs went to live in Sussex where Virginia had taken a five-year lease on Asheham House. It was to be another twelve years before Virginia moved back to Bloomsbury.

The intervening years 1912 -1924

During the years that Virginia was living elsewhere, she published four books and had, unfortunately, another serious mental breakdown from which she was slow to recover. The Woolfs moved to Hogarth House in Richmond and in 1917 they bought a hand-press – and so began Hogarth Press; soon they were printing pamphlets, books and slim volumes of poetry, mainly the works of the Bloomsbury Group.

The years spent at Tavistock Square were Virginia’s most productive and she became much sought after as a guest speaker at various prestigious universities.

Today, Tavistock Square is surrounded by a number of famous buildings, all of which are worth investigating. The Square was also the scene of the suicide bombings in 2005, in which 13 people were killed.

Mecklenburgh Square was Virginia Woolf’s final Bloomsbury residence. Like Brunswick Square, Mecklenburgh Square was part of the grounds of the Foundling Hospital and was named after King George III’s wife, Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg.

The 2 acres of gardens are beautifully laid out, with lawns, trees and pathways. The gardens are only open to the public on two days a year. The rest of the year, the gardens are only open to resident key-holders.

No. 37 which the Woolfs leased, was once again, a large terrace house facing the square. They operated the Hogarth Press from No 37. The house was badly damaged during the bombing of London in 1940.

In 1941, Virginia, fearing another onslaught of her mental condition, committed suicide by drowning herself in the River Ouse.

A walk through Bloomsbury is certainly an experience not to be forgotten. There is so much of interest – graceful, elegant architecture, quiet, peaceful gardens and the all-pervading atmosphere of intelligentsia.

It is no wonder that the Bloomsbury Group put down roots here and kept returning to the area throughout their lives.

After my walking tour was over, I certainly felt that I’d come to know Virginia Woolf and her group on a much more personal level.

References: 1975. Lehmann, John. Virginia Woolf and her World. London: Thames and Hudson.

♦ Contact www.walklondon-uk.com or www.walks.com for information about the tours, what is on offer, where to meet, etc. ♦ Wear comfortable shoes, take an umbrella and something to drink if it is hot. ♦ Don’t forget your camera and be prepared to walk for a good couple of hours, although the pace is not fast. ♦ The guides are knowledgeable and enjoy answering questions. Now is your opportunity to get answers to those questions you’ve always wanted to ask. ♦ Make the most of the tour and enjoy it.

Photo credits: Gordon Square, London by Paul the Archivist / CC BY-SA Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford / Public domain Bloomsbury group blue plaque by Edwardx / CC BY-SA Gordon Square park by Stephen McKay / Gordon Square, Bloomsbury Tavistock Square by Ewan Munro from London, UK / CC BY-SA

Browse London Historic Walking Tours Now Available

About the author: Lynn is a retired librarian who lives in Durban, South Africa. She lived in London for some time many years ago and has returned to visit several times in the past few years. Her last visits overseas were to Eastern Europe where she fell in love with Prague and Budapest. When not travelling, Lynn enjoys writing articles for the internet and does freelance editing and proof-reading. She is a keen gardener and shares her home with her six beloved cats.

[…] Literary London: Virginia Woolf’s Bloomsbury […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The Cornish Bird

Cornwall's Hidden History Blog

Virginia Woolf in Cornwall

Here we are on the verge of going to Cornwall. This time tomorrow we shall be stepping onto the platform at Penzance, sniffing the air, looking for our trap and then driving off across the moors to Zennor. Why am I so incredibly and incurably romantic about Cornwall? – Virginia Woolf, 22nd March 1921

Some places get under our skin. They become part of us, not just part of our history but part of our souls too. They influence and inspire us. From Virginia Woolf’s diary entry above it’s clear to see she had a long standing love affair with Cornwall. And throughout her often troubled life she was drawn back time and again to the place where she had been most happy. The place which had cast a spell over her in childhood and where she first began writing stories. The place that eventually became a refuge for her and a balm.

Where it all begins

Adeline Virginia Stephen was born in South Kensington in London in 1882. She was the seventh of eight children. Her family were highly educated, well off and spent every summer in St Ives in Cornwall. From the time Virginia was just a few months old, until her mother’s death when she was 12, the whole household would decamp, escape the constraints of London life and take the train west.

‘In retrospect nothing we had as children made as much difference, was quite so important to us, as our summer in Cornwall.’ – Woolf, A Sketch of the Past, 1940

The family always rented Talland House in St Ives. And this spacious house still exists, though it has now become a bit crowded in by modern development and has been seperated into flats.

Talland House stands on rising ground above Albert Road, high up on the hill overlooking the famous seaside town. In those early days it was an peaceful and idyllic haven.

Virginia’s father, the renowned literary critic and historian, Sir Leslie Stephen described the house was “a pocket paradise with a sheltered cove of sand in easy reach.”

The children spent their days playing in the garden and running wild on the beach. They fished and searching for seashells with salt on their skin. In those days the garden of Talland house was extensive. Full of nocks and hidden corners for imaginative exploring. Terraces, divided by high hedges, led all the way down to the sea. Virginia later described that time in Cornwall as her ‘most important memory’.

‘Lying half asleep, half awake, in bed in the nursery at St Ives. It is of hearing the waves breaking, one, two, one, two . . . It is of lying and hearing this splash and seeing this light, and feeling, it is almost impossible that I should be here; of feeling the purest ecstasy I can conceive.’

Godrevy Lighthouse

Wherever you are in St Ives the white vertical dash of Godrevy Lighthouse is always on the horizon. This iconic lighthouse became imbedded in Virginia’s mind. An image which she recreated in her contemplative book To The Lighthouse :

“For the great plateful of water was before her; the hoary Lighthouse, distant, austere, in the midst . . .”

Cornwall seeped in to much of her writing. In her diary in 1936, more than 40 years after those childhood summers Virginia, while pondering her passion for writing, wrote:

“I think it’s been absorbing ever since I was a little creature scribbling a story, in the manner of Hawthorne, on the green plush sofa in the drawing room at St. Ives, while the grown-ups dined.”

The End of Summer

Those hazy summers of freedom and sunshine came to an end with the death of Virginia’s mother, Julia Stephens. Julia was a beautiful and loving mother who had been a Pre-Raphaelite model before her marriage to her first husband.

She was just 49 years old when she died from influenza in 1895. Her death was a turning point, a tragic loss, that Virginia would struggle with for the rest of her life. It caused the first of her mental breakdowns at just 12 years old and the Stephens never returned to St Ives as a family again.

Virginia came back to Cornwall many times during her adult life, sometimes as single, independent woman and then later with her husband Leonard. Cornwall features, like a hazy shadow, in several of her books. The county drew her back time and again. An example of this pull can be seen from a letter that her sister Venessa Bell received in December 1909. Without warning or luggage Virginia had taken the 1pm train from Paddington to Cornwall and was writing from The Lelant Hotel (now the Badger Inn). Virginia explained:

“I went for a walk in Regent’s Park yesterday morning and it suddenly struck me how absurd it is was to stay in London with Cornwall going on all the time . . .”

She arrived at Lelant station late on Christmas Eve, without her glasses, chequebook or coat, and made her way up the steep hill to the nearest accomodation. The Badger Inn. But she seems just content to be there.

“I am so drugged with the fresh air that I can’t write, and now my ink fails. As for the beauty of this place, it surpasses every other season. I have the hotel to myself – and get a very nice sitting room for nothing. It is very comfortable and humble, and infinitely better than the Lizard or St Ives.”

The landlords at the time, Thomas and Sarah Dunstan, had no other guests and must have been surprised at their late, unannounced arrival. Lelant is a small village a few miles from St Ives. It overlooks the same sweeping bay she knew from her childhood holidays and the same endless stretch of golden sand that runs for three miles to the Godrevy Lighthouse. Virginia wrote:

“Then there is the lighthouse seen through the steamy glass, and a grey flat where the sea is. There is no moon or stars but the air is soft as down.”

Virginia seems to have spent that impromptu Christmas break in 1909 walking alone in the Cornish countryside.

“After dinner is a very pleasant time . . . as one sits by the fire thinking how one staggered up Trencrom in the mist this afternoon, and sat on a granite tomb on the top, and surveyed the land, with the rain dripping against one’s skin . . .”

Trencrom is a hill topped with an Iron Age hillfort close to Lelant with extensive views of both St Ives Bay and Mounts Bay. It is a place full of history and legend and unchanged as it is, it is easy to imagine Virginia sitting there in the rain.

She also wrote to her friend Violet Dickinson on the 27th December:

“I have been tramping about the country, and dabbling in the Atlantic. It is as soft as spring and at ten at night I sit with my window open. Old farmers are saying good night and calling the weather dirty beneath me. How anyone with an immortal soul can live inland I can’t imagine. Only clods and animals should be able to endure it.”

Another return visit was under less free or festive circumstances. Just a year after her spontaneous journey to Lelant Virginia was back in Cornwall. This time staying near the village of Zennor .

She had been finishing her first novel, The Voyage Out, when she suffered a serious mental breakdown. It was so severe that she was taken to ‘Burley’, 15 Cambridge Park, Twickenham. A specialist home for women Virginia was to receive treatment here on three different occasions. In 1910, when she had recovered a little, it was decided that she should go to Cornwall, accompanied by a nurse, to recuperate. Virginia and Ms. Jean Thomas spent nearly a month at Lower Porthmeor, from 16th August until 6th Sept. They occupied their time by taking long, invigorating walks across the moors .

Virginia later wrote of the area:

“This is the loveliest place in the world. It is so lonely.”

From then on she returned to Zennor often. In 1919 with her husband Leonard Woolf, renting the same cottage used by D H Lawrence at Tregethen. And again in 1921 and 1926, sometimes staying the writer’s haunt the Eagles Nest. They also stayed at Carbis Bay in 1914 for a while too. This time Virginia was recovering from a suicide attempt and another of her recurring bouts of depression. Cornwall it seems was always a safe and comforting haven for her.

Her last visit

In May 1936 Virginia and Leonard set out on a road trip of the south west of England. This holiday was to be Virginia’s last visit to Cornwall and the couple again stayed at the Eagles Nest near Zennor.

They took a day trip to St Ives and visited Talland House one final time. Leonard poignantly wrote that “Virginia peered through the ground floor windows to see the ghosts of her childhood.”

She died in 1941.

Tracking Down Virginia

It is relatively easy to see some of the places that Virginia Woolf stayed in Cornwall. You could pop into The Badger Inn in Lelant and have something to eat in the same lounge area that Virginia used. Talland House is within walking distance of St Ives railway station.

* But it is important to remember however that the houses she stayed in are privately owned now, so not really tourist a ttractions!

Both Tregerthen and the Eagles Nest can been seen between Zennor and the Carracks on this scenic circular walk. You can also ‘visit’ Lower Porthmeor, where Virginia stayed with her nurse, on a walk from Rosemergy to Gurnards Head. This route actually passes through the cottage’s garden.

I provide all the content on this blog completely FREE, no subscription fee. If however you enjoy my work and would like to contribute something towards helping me keep researching and writing about Cornwall’s amazing history and places you can donate below. Thank you!

Further Reading:

Daphne du Maurier at Menabilly

Beatrix Potter in Cornwall

Trencrom – a fort with a view

Sherlock Holmes in Cornwall – The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot

Turner in Cornwall – Follow in the artist’s footsteps

Things to do in St Ives

Find inspiration for more things to do in the St Ives area HERE

Share this:

9 thoughts on “ virginia woolf in cornwall ”.

I know just how she felt in Regents Park! Sometimes I also get the urge to just keep driving until I reach the sea! Really interesting read.

Me too!! And I live here 😆 And thank you!

Great post. As ever 🙂

Thank you 😊

Really enjoyed your post, great fan of To The Lighthouse and I always treasure my glimpses of Godrevy.

Thank you for this extended piece about Woolf’s connection with Cornwall. It’s funny that my knowledge of Woolf and my interest in Cornwall hadn’t really connected in my mind until I read your essay.

Like you, I am a keen follower of Cornish Bird’s wonderful blog, Elizabeth. This post was particularly timely for me, having so recently written about Flush 🙂

She is such a thoughtful and detailed writer.

Very interesting blog post, thank you.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from The Cornish Bird

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Whoa, nelly! It's time to upgrade your browser for a better experience. Until then, this website may not work as intended.

How Should One Read a Book?

by Virginia Woolf

In the first place, I want to emphasise the note of interrogation at the end of my title. Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions — there we have none.