Queen Victoria: how and why did she become Empress of India?

When control of the subcontinent came under the British Crown in 1858, it marked the start of a turbulent relationship. Writer Lottie Goldfinch explains how Queen Victoria fell in love with a country she never stepped foot in

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

On 1 January 1877, while Queen Victoria was quietly celebrating the new year with her family at Windsor Castle, a spectacular celebration was taking place more than 4,000 miles away in Delhi, India, to mark the Queen’s new imperial role as Empress of India. Determined to flaunt the power and majesty of the British Raj, Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India, chose to revive Mughal traditions for the extravaganza, confident that it would be well received. A plan was coordinated to present leading Indian chiefs and princes with shield-shaped silk banners emblazoned with their coat of arms, albeit in a deliberate European style – “the further east you go, the greater becomes the importance of a bit of bunting”, the Viceroy is recorded as saying. By the end of 1876, more than 400 Indian princes, chiefs, officials and their retinues had gathered together in Delhi in preparation for the grand ceremony.

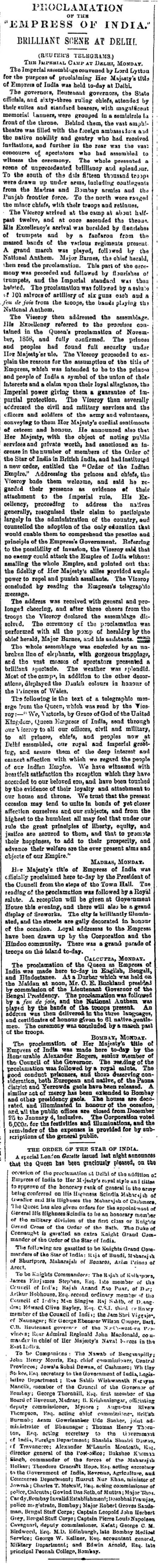

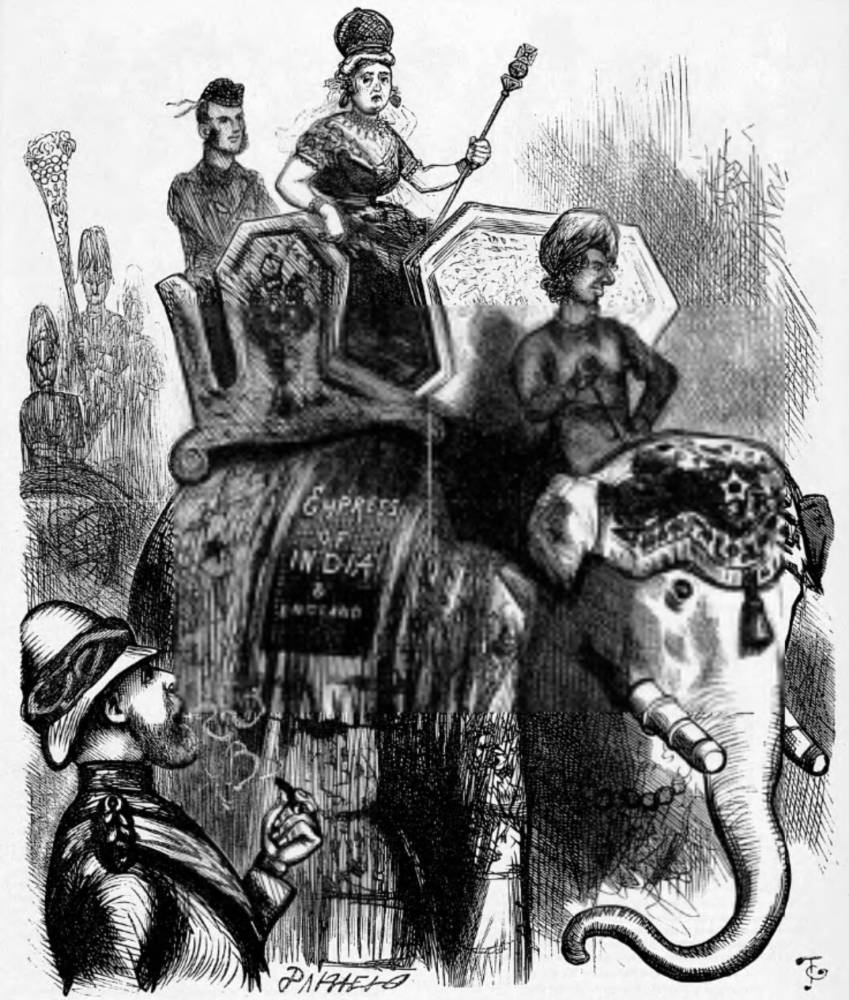

The resulting pageant was a sumptuous demonstration of British authority. The Viceroy and his family processed through the streets of Delhi on elephants, entering the specially constructed Throne Pavilion to a fanfare of trumpets and royal salutes.

For the proclamation ceremony itself, Lord Lytton sat enthroned beneath a huge portrait of Queen-Empress Victoria. Facing him were 63 ruling Indian chiefs, “all in gorgeous costumes of satin, velvet or cloth of gold”. A telegram sent by Lytton to the Queen later that day expressed his satisfaction and delight at the occasion: “There can be no question of the complete success of this great imperial ceremony,” he announced happily.

The road to India

The elaborate proclamation ceremony may have, on the surface at least, neatly papered over the cracks in Anglo-Indian relations, but resentment and anger at British involvement in Indian affairs had been simmering for more than 300 years, well before Victoria came to the throne.

British presence in India had begun in 1600, with the formation of the East India Company (EIC) – a company whose purpose was to exploit trade with East and Southeast Asia and India. For years, Britain had desired a share in the rich and profitable East Indian spice trade monopolised by Spain and Portugal, and in 1588, the defeat of the Spanish Armada had helped break European domination of the market. Despite Dutch opposition, England won trading concessions from the Mughal Empire and began to trade in cotton and silk, fabric goods, indigo dye, saltpetre (used to preserve meat and also make explosives) and spices.

More like this

Resentment and anger at British involvement in Indian affairs had been simmering for more than 300 years, well before Victoria came to the throne

The Company’s first ships arrived at the Indian port of Surat in 1608, and in 1619 a factory was established in the same city with the permission of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. By the 18th century, the EIC had expanded massively, eclipsing its European rivals and establishing several trading posts and communities along the east and west coasts of the Indian subcontinent.

But in 1757, the company’s fortunes took a different turn. East India Company civil-servant-turned-militaryman, Robert Clive, defeated the Nawab (governor) of Bengal and his French allies at the Battle of Plassey. It was a clash that, in part, had erupted over EIC abuse of the trade privileges that had been granted to them.

The British victory enabled the company to take over the administration of large parts of India, with British communities established around Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. Seven years later, the young Mughal emperor Shah Alam too was defeated by EIC troops and exiled from Delhi. His Mughal revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa were replaced by a set of English traders who had been appointed by Clive, who was now governor of Bengal.

The impact on the Indian states under the company’s rule was disastrous

From this moment, the EIC morphed from an international trading corporation into a privately owned colonial power, becoming the effective rulers of Bengal and expanding its territory at an alarming rate.

The impact on the Indian states under the company’s rule was disastrous. Far from wishing to preserve and nurture its newly gained territories, men of the EIC plundered and pillaged Bengal, leaving it in a state of destitution. Crippling taxes destroyed the economic resources of the rural population, compounded by a devastating famine between 1769 and 1773, which is thought to have caused the deaths of up to 10 million people.

Indian influence on Britain

Huge military expenditure saw the EIC run into serious financial difficulties, and in 1773, the British government was forced to step in and help the ailing company, with William Pitt’s India Act of 1784 seeking to bring it under closer parliamentary supervision, namely through the rule of a governor-general.

But the EIC continued to expand and by 1803, its reach extended up the Ganges valley to Delhi and across most of the peninsula of southern India. Fifteen years later, the EIC had become the main political power in India, with direct control over around two thirds of the subcontinent.

Early empire

When Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, few would have predicted how far British influence would spread during her reign. Imperial expansion had been haphazard, and predominately the result of victory in military conflicts or settlements founded by Britons seeking new lives abroad.

At the start of the 19th century, most of Britain’s jumbled collection of territories – such as Canada, South Africa and Guiana – had been unintentionally acquired by previous monarchs, rather than as a result of a deliberate programme of expansion. These territories were only partly administered by government, with chartered companies such as the East India Company holding significant power.

At her accession, the inexperienced Queen was initially content to follow the instruction of her advisors when it came to matters of foreign policy. But, with eleven wars fought during the first quarter of her reign alone, Victoria soon began to take a keen interest in British affairs abroad. Although she no longer had the power to make or break governments as she saw fit, Victoria took her queenly duty to advise, consult and warn seriously, and ultimately helped shape government policy.

British influence on India

One of her chief demands was that military consequences be considered first and foremost, if Britain was to pursue the type of aggressive foreign policy that it had become famous for in the 19th century. Supportive though she was of Britain’s imperial ‘duty’ to spread civilisation to the darkest corners of the globe, Queen Victoria was deeply concerned for the fate of the ordinary solider who was putting his life on the line for his country.

But the people Victoria sought to rule did not take British colonisation lying down. One of the biggest events of her rule took place in India, where, in 1857, widespread unrest at increasing westernisation, challenges to traditional Hindu culture and British dominance in all areas of Indian life exploded into a mass uprising against the EIC’s rule and the authority of the British Crown.

The rebellion began in March 1857, when an Indian sepoy (soldier) named Mangal Pandey attacked officers at the garrison in Barrackpore, North Calcutta, and was subsequently executed. A few weeks later, trouble erupted again when a group of solders were imprisoned at Meerut for refusing to use gun cartridges rumoured to have been greased in pork fat, as it offended their religious beliefs. The two incidents and the harsh punishments inflicted on the perpetrators led to a military uprising in May, which saw Indian soldiers shoot their British officers and march on Delhi. Word spread quickly, and similar mutinies took place across all of northern India.

The British acted quickly to suppress the rebellion, and the desperate struggles for Indian independence were quelled in a flurry of bloodshed. Thousands of sepoys were bayoneted or fired at with cannons, and even women and children failed to escape the reprisals. Around 100,000 Indian soldiers are believed to have died in the mutiny, although historian Amaresh Misra claims that British reprisals continued for a decade after the event, with millions more killed.

British imperial duty

When news of the uprising reached Britain, there was widespread public horror at the level of bloodshed on both sides of the conflict. Newspaper headlines shouted of the massacre of captured Europeans – including women and children – by the rebels, as well as the indiscriminate killing of Indian civilians at the hands of the British armies.

Queen Victoria herself followed the uprising closely, writing in her diary for 3 August: “Dreadful details in the papers of the horrors committed in India on poor ladies and children, who were murdered with revolting barbarity! An awful state, and the crisis, in every sense, an alarming one…”

But despite widespread condemnation of the violence, voices of sympathy to those involved were also raised, and many Britons – including Victoria – still retained a sense of imperial duty that continued to have a profound influence on its colonial expansion. In places like India and Africa, this had historically manifested in an influx of Christian evangelicals, many of whom sought to convert native peoples to Christianity.

The nation was divided between those who believed it was Britain’s duty to Christianise the people of its empire, and those who believed that those living in its colonies would never be able to reach the same level of development as those living in Britain.

People such as Cecil Rhodes, a dedicated imperialist, believed the empire should be run and ultimately populated by members of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ race, who had a duty to found colonies and populate them with men and women who would advance Britain’s power.

“There is a destiny now possible for us, the highest ever set before a nation… This is what England must do or perish: she must found colonies as fast and as far as she is able, formed of her most energetic and worthiest men; seizing every bit of fruitful waste ground she can set her foot on, and there teaching these her colonists that the chief virtue is to be fidelity to their country and their first aim… to advance the power of England.”

Royal response

Like many of her subjects, Victoria, while believing in many of the ideals of empire, was not wholly unsympathetic to the men and women of the nations she wished to rule, and had reservations about some of the methods of colonisation employed.

In the wake of the Indian Rebellion, the British Parliament had passed the Government of India Act, which transferred the administrative authority and rights of the EIC to the British Crown. Wishing to reassure the Indian people of their rights as British subjects and to help restore peace in the country, Victoria issued a proclamation on 1 November 1858 that became known as ‘the Magnacarta of the People of India’. In it, Victoria stated that Britain desired “no extensions of Our present territorial possessions” and promised to “respect the rights, dignity, and honour of Native Princes as Our own”.

Religious toleration was also assured with the line “we disclaim alike the Right and Desire to impose our Convictions on any of Our Subjects” with “none molested or disquieted by reason of their Religious Faith or Observances…” And with that, India was annexed to the British Empire.

Of course, ruling a country as vast as India would not have been possible without the cooperation of its princes and local leaders. During the period that followed the 1857 rebellion – known as the British Raj – some 20,000 British troops and officials were able to govern 300 million Indian people with relatively little trouble. Some historians have attributed this to British divide and rule techniques, which played on the many divisions in Indian society, while others have claimed that India was actually accepting of British rule and the benefits it brought.

Life in the British Raj

Although she didn’t officially assume the title of Empress of India until 1877, Victoria’s keenness to elevate her royal title was evident as early as 1873 when she complained to her secretary Henry Ponsonby: “I am an Empress and in common conversation am sometimes called Empress of India. Why have I never officially assumed this title?”

Her eagerness to assume the title had begun in 1871, following William I of Prussia’s elevation to Emperor. Victoria’s daughter, Vicky, who was married to William’s son Frederick would therefore become Empress when her husband took the throne, effectively outranking her mother. Victoria was not amused. Prussia, Russia and Austria all had emperors and Victoria felt unable to compete unless she, too, assumed the title.

Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was the force behind overcoming parliamentary opposition and in 1877, Victoria became Empress of India, sealing the relationship between Britain and India. It also marked the beginning of the Queen’s love affair with India and became a symbol of the responsibility she felt towards her Indian subjects.

A passion for Indian culture swept through Britain

Although she never visited the subcontinent – her son Edward VII would be the first British monarch to set foot on Indian soil – Victoria had a particular fascination with the country, and a passion for Indian culture swept through Britain in the late 19th century. Victoria’s love of curry is well documented, while at Osborne House , the royal family’s Isle of Wight seaside retreat, the magnificent Durbar room was added in 1890-92, designed by John Lockwood Kipling and Sikh architect Bhai Ram Singh. Built for state functions, the room boasts intricate Indian-style plaster work and exhibited the Queen’s magnificent collections of gifts from Indian princes.

Britain’s wider relationship with India - the jewel in the crown of the empire – would continue for nearly half a century more, however, with both Edward VII and George V retaining the title Victoria had fought so hard for. British rule would end eventually – with as much pomp and circumstance as it had begun – but to this day, ties with India remain as hardy as the toughest diamond.

What happened next?

Q&a: the impact of british rule in india.

Lottie Goldfinch is a freelance journalist specialising in history

This article was first published in the November 2017 edition of BBC History Revealed

JUMP into SPRING! Get your first 6 issues for £9.99

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership (special offers) - worth £34.99!

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

JUMP into SPRING! Get your first 6 issues for

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

Biography of Queen Victoria, Queen of England and Empress of India

She ruled during a time of economic and imperial expansion

Hulton Royals Collection / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- Important Figures

- History Of Feminism

- Women's Suffrage

- Women & War

- Laws & Womens Rights

- Feminist Texts

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- B.A., Mundelein College

- M.Div., Meadville/Lombard Theological School

Queen Victoria (May 24, 1819–January 22, 1901), was the queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the empress of India. She was the longest-ruling monarch of Great Britain until Queen Elizabeth II surpassed her record and ruled during a time of economic and imperial expansion known as the Victorian Era.

Fast Facts: Queen Victoria

- Known For : Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (r. 1837–1901), Empress of India (r. 1876–1901)

- Born : May 24, 1819 in Kensington Palace, London, England

- Parents : Edward, Duke of Kent and Victoire Maria Louisa of Saxe-Coburg

- Died : January 22, 1901 in Osborne House, Isle of Wight

- Published Works : Letters , Leaves From the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands , and More Leaves

- Spouse : Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (m. Feb. 10, 1840)

- Children : Alice Maud Mary (1843–1878), Alfred Ernest Albert (1844–1900), Helena Augusta Victoria (1846–1923), Louise Caroline Alberta (1848–1939), Arthur William Patrick Albert (1850–1942), Leopold George Duncan Albert (1853–1884), Beatrice Mary Victoria Feodore (1857–1944)

Queen Victoria's children and grandchildren married into many royal families of Europe, and some introduced the hemophilia gene into those families. She was a member of the house of Hanover , later called the house of Windsor.

Queen Victoria was born Alexandrina Victoria at Kensington Palace, London, England on May 24, 1819. She was the only child of Edward, Duke of Kent (1767–1820), the fourth son of King George III (1738–1820, r. 1760–1820). Her mother was Victoire Maria Louisa of Saxe-Coburg (1786–1861), sister of Prince (later King) Leopold of the Belgians (1790–1865, r. 1831–1865). Edward had married Victoire when an heir to the throne was needed after the death of Princess Charlotte, who had been married to Prince Leopold. Edward died in 1820, just before his father did. Victoire became the guardian of Alexandrina Victoria, as designated in Edward's will.

When George IV became king (r. 1821–1830), his dislike for Victoire helped isolate the mother and daughter from the rest of the court. Prince Leopold helped his sister and niece financially.

In 1830 and at the age of 11, Victoria became heir-apparent to the British crown on the death of her uncle George IV, at which point the parliament granted her income. Her uncle William IV (1765–1837, r. 1830–1837) became king. Victoria remained relatively isolated, without any real friends, though she had many servants and teachers and a succession of pet dogs. A tutor, Louise Lehzen (1784–1817), tried to teach Victoria the kind of discipline that Queen Elizabeth I had displayed. She was tutored in politics by her uncle Leopold.

When Victoria turned 18, her uncle King William IV offered her a separate income and household, but Victoria's mother refused. Victoria attended a ball in her honor and was greeted by crowds in the streets.

When William IV died childless a month later, Victoria became Queen of Great Britain and was crowned June, 20, 1837.

Victoria began to exclude her mother from her inner circle. The first crisis of her reign came when rumors circulated that one of her mother's ladies-in-waiting, Lady Flora, was pregnant by her mother's adviser, John Conroy. Lady Flora died of a liver tumor, but opponents at court used the rumors to make the new queen seem less innocent.

Queen Victoria tested the limits of her royal powers in May 1839, when the government of Lord Melbourne (William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, 1779–1848), a Whig who had been her mentor and friend, fell. She refused to follow established precedent and dismiss her ladies of the bedchamber so that the Tory government could replace them. In the "bedchamber crisis" she had the support of Melbourne. Her refusal brought back the Whigs and Lord Melbourne until 1841.

Neither Victoria nor her advisers favored the idea of an unmarried queen, despite or because of the example of Elizabeth I (1533–1603, r. 1558–1603). A husband for Victoria would have to be royal and Protestant, as well as an appropriate age, which narrowed the field. Prince Leopold had been promoting her cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819–1861) for many years. They had first met when both were 17 and had corresponded ever since. When they were 20, he returned to England and Victoria, in love with him, proposed marriage. They were married on Feb. 10, 1840.

Victoria had traditional views on the role of wife and mother, and although she was queen and Albert was prince consort, he shared government responsibilities at least equally. They fought often, sometimes with Victoria shouting angrily.

Their first child, a daughter, was born in November 1840, followed by the Prince of Wales, Edward, in 1841. Three more sons and four more daughters followed. All nine pregnancies ended with live births and all the children survived to adulthood, an unusual record for that time. Although Victoria had been nursed by her own mother, she used wet-nurses for her children. Though the family could have lived at Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, or the Brighton Pavilion, they worked to create homes more appropriate for a family. Albert was key in designing their residences at Balmoral Castle and Osborne House. The family traveled to several places, including Scotland, France and Belgium. Victoria became especially fond of Scotland and Balmoral.

Government Role

When Melbourne's government failed again in 1841, he helped with the transition to the new government to avoid another embarrassing crisis. Victoria had a more limited role under Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (1788–1850), with Albert taking a lead for the next 20 years of "dual monarchy." Albert guided Victoria to an appearance of political neutrality, though she didn't become any fonder of Peel. Instead, she became involved with establishing charities.

European sovereigns visited her at home, and she and Albert visited Germany, including Coburg and Berlin. She began to feel herself part of a larger network of monarchs. Albert and Victoria used their relationship to become more active in foreign affairs, which conflicted with the ideas of the foreign minister, Lord Palmerston (Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, 1784–1865). He didn't appreciate their involvement, and Victoria and Albert often thought his ideas too liberal and aggressive.

Albert worked on a plan for a Great Exhibition, with a Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. Public appreciation for this construction completed in 1851 finally led to a warming of the British citizens toward their queen's consort.

In the mid-1850s, the Crimean War (1853–1856) engrossed Victoria's attention; she rewarded Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) for her service in helping protect and heal soldiers. Victoria's concern for the wounded and sick led to her founding Royal Victoria Hospital in 1873. As a result of the war, Victoria grew closer to the French emperor Napoleon III and his empress Eugénie. Napoleon III (1808–1873) was president of France from 1848–1852, and when he was not reelected, seized power and ruled as an emperor from 1852–1870.

The unsuccessful revolt of Indian infantrymen in the army of the East India Company known as the Mutiny of the Sepoys (1857–1858) shocked Victoria. This and subsequent events led to British direct rule over India and Victoria's new title as empress of India on May 1, 1876.

In family matters, Victoria became disappointed with her eldest son, Albert Edward, prince of Wales, heir presumptive. The eldest three children—Victoria, "Bertie," and Alice—received better educations than their younger siblings did, as they were most likely to inherit the crown.

Queen Victoria and the Princess Royal Victoria weren't as close as Victoria was to several of the younger children; the princess was closer to her father. Albert won his way in marrying the princess to Frederick William, son of the prince and princess of Prussia. The young prince proposed when Princess Victoria was only 14. The queen urged delay in marriage to be sure that the princess was truly in love, and when she assured herself and her parents that she was, the two were formally engaged.

Albert had never been named prince consort by parliament. Attempts in 1854 and 1856 to do so failed. Finally in 1857, Victoria conferred the title herself.

In 1858, Princess Victoria was married to the Prussian prince. Victoria and her daughter, known as Vicky, exchanged many letters as Victoria attempted to influence her daughter and son-in-law.

A series of deaths among Victoria's relatives kept her in mourning starting in 1861. First, the king of Prussia died, making Vicky and her husband Frederick crown princess and prince. In March, Victoria's mother died and Victoria collapsed, having reconciled with her mother during her marriage. Several more deaths in the family followed, and then came a scandal with the prince of Wales. In the middle of negotiating his marriage with Alexandra of Denmark, it was revealed that he was having an affair with an actress.

Then Prince Albert's health failed. He caught a cold and couldn't shake it. Perhaps weakened already by cancer, he developed what may have been typhoid fever and died on Dec. 14, 1861. His death devastated Victoria; her prolonged mourning lost her much popularity.

Eventually coming out of seclusion in February 1872, Victoria maintained an active role in government by building many memorials to her late husband. She died on January 22, 1901.

Her reign was marked by waxing and waning popularity, and suspicions that she preferred the Germans a bit too much diminished her popularity. By the time she had assumed the throne, the British monarchy was more figurehead and influence than it was a direct power in the government, and her long reign did little to change that.

Queen Victoria's influence on British and world affairs, even if often was a figurehead, led to the naming of the Victorian Era for her. She saw the largest extent of the British empire and the tensions within it. Her relationship with her son, keeping him from any shared power, probably weakened the royal rule in future generations, and the failure of her daughter and son-in-law in Germany to have time to actualize their liberal ideas probably shifted the balance of European history.

The marriage of her daughters into other royal families and the likelihood that her children bore a mutant gene for hemophilia affected the following generations of European history.

- Baird, Julia. "Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire." New York: Random House, 2016.

- Hibbert, Christopher. "Queen Victoria: A Personal History. " New York: Harper-Collins, 2010.

- Hough, Richard. "Victoria and Albert." New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

- Rappaport, Helen. "Queen Victoria: A Biographical Companion." Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2003.

- How Was Queen Victoria Related to Prince Albert?

- Queen Victoria's Children and Grandchildren

- Biography of Prince Albert, Husband of Queen Victoria

- Women Rulers of England and Great Britain

- Queen Victoria Trivia

- Germanic Trivia: The Houses of Windsor and Hanover

- Biography of Princess Louise, Princess Royal and Duchess of Fife

- How Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip Are Related

- Empress Carlota of Mexico

- Queen Victoria's Death and Final Arrangements

- The Relationship Between Queen Elizabeth II and Queen Victoria

- Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee

- Anne of Hanover, Princess of Orange

- Biography of Elizabeth of York, Queen of England

- Biography and Facts About Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon

- Biography of Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England

15th August, 2017 in History , Society & Culture

India from Queen Victoria’s time to independence

By Shrabani Basu

Queen Victoria became Empress of India in May 1876. Benjamin Disraeli, the Conservative Prime Minister, saw the new title as an effort to link the monarchy to the country and tie it closer to Britain while also showcasing Britain as a dominant world power. India had been under crown rule since 1858, and before this under the dominion of the East India Company, who took control in 1757.

The Queen delighted in her new title and wrote in her diary, ‘my thoughts much too taken up with the great event at Delhi today, & in India generally, where I am being proclaimed Empress of India.’ A field report from Delhi stated that ‘a salute of one hundred and one salvos of artillery was fired. This was too much for the elephants…they became more and more alarmed, and at last scampered off, dispersing the crowd in every direction.’

Queen Victoria took her duties as Empress very seriously and when her Golden Jubilee came around in 1887 she made every effort to showcase her ‘jewel in the crown of the British Empire’. She hosted lavish banquets and parties for Indian princes and European nobility and rode in elaborate processions accompanied by the Colonial Indian cavalry. Indian attendants were brought to the royal household to help with the festivities as well. Victoria took a liking to one of her new servants in particular: Abdul Karim. Soon the twenty-four-year-old’s role changed from patiently waiting at tables to teaching the Queen to read, write and speak in Urdu, or ‘Hindustani’. The Queen wanted to know everything about India, a place where she ruled but could never visit. Abul told her all about Agra, from the local fruits and spices to the sights and sounds of his homeland. It was not long before he became her ‘Munshi’, or teacher, and they began a friendship that would last over a decade.

To Queen Victoria India was both an exotic, faraway place and also a country to be ruled. She put her opinions on governance – and sometimes those of her trusted Munshi – forward in her frequent letters to the Viceroy often with severe underlining to emphasise her points. For example, Abdul described the riots that sometimes broke out in Agra when the Muslims had the religious procession of Muharram to mark the martyrdom of Hussain, the grandson of the Prophet, and it clashed with the Hindu procession of Sankranti. The Queen responded by writing immediately to Viceroy Lord Dufferin, requesting he take ‘some extra measure to prevent this painful quarrelling’ so that the Muslims could carry out their ceremonies ‘quietly and without molestation’ and ‘give strict orders and prevent the Mahomedans and the Hindus from interfering with one another, so that perfect justice is shown to both.

India in Victoria’s time was rife with such unrest, in addition to sweeping famine and widespread change. The census of 1871 aimed to record the age, caste, religion, occupation and education level of the entire population in order to better govern. It found the total population to be 238,830,958. British-born subjects in India (excluding the army and navy) numbered just 59,000. India is now the second most populated country in the world with 1,326,801,576 residents as of July 2016. The population density in England in 1871 was 422 people per square mile on average, whereas in India it ranged from 468 in Oude to just 31 in British Burma. The census of 1871 failed to fully report on Indian subject’s level of education, but came to the conclusion that only around one in 30 men (women were not included in these reports) had received the ‘barest rudiments’ of education. In 2016 81% of Indian men over 15 years and 61% of women were literate. The census also found the population to be expanding at the rate of 3% annually, which the report writers thought to be ‘an improvement doubtless due to the better administration of the country since it came under the British rule.’

On 15 August 1947 India regained its independence and 200 years of British rule came to an end. The Radcliffe Line was drawn to separate the officially Muslim Dominion of Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) from the officially secular Union of India. This partition sparked the largest mass migration in history and at least one million people died from religious violence. Abdul Karim’s descendants had to flee their home too:

As Hindus and Muslims rioted in the streets of Agra, the women and children were sent in the dead of night to Bhopal in central India. From Bhopal they took the train to Bombay (the women hiding their jewellery in their saris) and finally an overcrowded ship to Karachi, joining the thousands of refugees leaving for Pakistan. Two trunks full of precious artefacts were sent on the goods train to Pakistan. The train was looted and the treasures never arrived. Abdul Karim’s diary, some pictures and artefacts including the tea set gifted by the Tsar of Russia and a statuette of Abdul Karim did make it, carried on the boat by the men of the family.

The areas of Punjab and Bengal were particularly violent, with villages divided between the two brand new countries. Although Viceroy Louis Mountbatten originally planned to leave in 1948 he brought the date forward to August 1947, and the British left the fledgling governments in a state of civil unrest with high religious tensions.

India has transformed radically since the Victorian era, by both statistical measures and cultural changes. It has endured world wars, upheavals, civil unrest and the fight for independence and yet Abdul Karim’s homeland is still a place that he could ‘gently describe’ as a ‘paradise that was as sad as it was beautiful.’

More articles you might like

13th March, 2024 in Society & Culture

Ask the Author: Kristofer Allerfeldt on the Ku Klux Klan – An American history

Author Kristofer Allerfeldt is a professor of US history at the University of Exeter. He has written articles, both popular and academic; and lectured in Europe, the UK and the US. He has also produced four academic books. The Ku Klux Klan is his new book which seeks to demystify…

12th March, 2024 in Biography & Memoir , Society & Culture

Vanity Fair and trailblazing on Savile Row

One day, we got a phone call from Vanity Fair saying the photographer Michael Roberts would like to shoot us on Savile Row. Michael was something of a trailblazer himself. Only a couple of years earlier, he had shot Vivienne Westwood impersonating Margaret Thatcher for the cover…

7th March, 2024 in Society & Culture , Women in History

Daisy Hopkins: The prostitute who fought against being imprisoned by Cambridge University

Cambridge University is internationally renowned for its ancient colleges. It is lauded for its educational excellence. But in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, infamy blighted its hallowed name. As an alarming number of courtroom dramas exposed the university’s steadfa…

24th November, 2023 in Biography & Memoir , History , Special Editions

Solving the mystery of the Princes in the Tower

Following seven years of investigation and intelligence gathering, including archival searches around the world, Phase One of The Missing Princes Project is complete. The evidence uncovered suggests that both sons of Edward IV survived to fight for the English throne against Henr…

15th November, 2023 in History , Trivia & Gift

Charades for Christmas

In 1895 there appeared an anonymous private booklet of the charades and theatrical conundrums written by the Austen family for their own entertainment. This offers yet another glimpse of the delightful Christmases the Austens enjoyed in their home, particularly at Steventon. Char…

18th October, 2023 in Biography & Memoir , History

Nobody Lives Here: A wartime Jewish childhood

This memoir is a gripping and unusual account of a survivor of the Shoah in Holland. With impressively clear recall of his childhood and early teens – he was 11 at the outbreak of the war – Lex Lesgever writes of his years on the run and in hiding in Amsterdam and beyond. It is u…

6th September, 2023 in History , Women in History

The forgotten Boleyn

Shortly after the midsummer festivities of 1458 a more sombre procession wound its way towards the parish church of St Andrew’s in the Norfolk village of Blickling. Amongst the mourners was borne the body of Cecily Boleyn, whose soul had departed to God on 26 June and whose morta…

15th August, 2023 in History , Military

Siege warfare in the Middle Ages

In the medieval era, pitched battles were risky affairs; the work of years could be undone in a single day thanks to the vagaries of weather, terrain or simple bad luck. C.B. Hanley author of the Mediaeval Mystery series, including the latest addition Blessed…

11th May, 2023 in History , Women in History

Five things you may not know about Lady Katherine Grey

Learn more about the life and reign of Lady Katherine Grey, great-granddaughter of the first Tudor king, Henry VII, and sister of the ill-fated Lady Jane. 1. Although James VI of Scotland succeeded Elizabeth I upon her death in 1603, he was not the rightful successor according to…

4th May, 2023 in History , Society & Culture , Women in History

Wealth, poverty, and childbirth in Victorian Britain

What was it like to give birth in Victorian Britain? Much depended, of course, on individual circumstances: health, wealth, social – including marital – status, and access to medical care. For the Queen for whom the period is named, childbirth was a painful, in some respects unwe…

19th April, 2023 in History

Long Live the King! Coronations throughout history

The main elements of the coronation of King Charles III can be traced back to Pentecost 973, when King Edgar ‘convoked all the archbishops, bishops, judge and all who had rank and dignity’ to assemble at Bath Abbey to witness his consecration as monarch. There was no set venue fo…

18th April, 2023 in Biography & Memoir , History , Society & Culture

The Butcher of the Balkans: Andrija Artuković

Fate called Andrija Artuković out of exile, back to his homeland. It was time to start building the Croatia that he’d been fighting for his entire adult life. At the age of 41, Artuković was assigned an important post in Ante Pavelić’s new cabinet: Minister of the Interior, taske…

13th April, 2023 in History , True Crime

Hawkhurst: The story of smuggling in the 18th Century

In his new book Hawkhurst: Murder, Corruption, and Britain’s Most Notorious Smuggling Gang author Joe Dragovich covers a fascinating era that is underrepresented in non-fiction historical true crime… 18 December 1744 John Bolton sat in the King’s Head Inn in Shoreham in Kent. W…

23rd February, 2023 in History , Society & Culture , True Crime

How a story of Ethiopian plunder started in a Scottish cupboard

My book was born on a cold winter afternoon when a train pulled into Edinburgh’s Waverley Station. Out walked a group of black-robed priests, led by the archbishop of the ancient Ethiopian city of Axum. Close behind came diplomats, officials, a delegation of Rastafarians from the…

1st February, 2023 in Society & Culture

10 LGBTQ+ history icons you may not have heard of

June marks the beginning of Pride month. A month-long celebration and recognition of the LGBTQIA+ community, the history of gay rights and relevant civil rights movements. To commemorate this, we’re highlighting some people throughout history that may not be as well known but are…

25th January, 2023 in Archaeology , History

The world of the Roman chariot horse

‘The horses burst through the sky and with swift-hooved feet cut a dash through the clouds, which blocked their way as borne on wings they passed the east wind.’ (Ovid, Metamorphoses II.157–60) The Formula One of the Roman world was the high-adrenalin sport of chariot racing wher…

9th September, 2022 in Biography & Memoir , History , Women in History

The reign of Queen Elizabeth II: A timeline

On 8 September 2022, Buckingham Palace announced that Queen Elizabeth II had died at the age of 96, after reigning for 70 years. Elizabeth succeeded to the throne in 1952 at the age of 25, following the death of her father, King George VI. As the monarch of the United Kingdom and…

24th August, 2022 in Biography & Memoir , History

Breakspear: More cannons than canon

‘The English reader may consult the Biographia Britannica for Adrian IV but our own writers have added nothing to the fame or merits of their countryman.’ – Edward Gibbon [1] Nicholas Breakspear was elected pope in 1154, choosing Adrian as his papal name. He is the first and so f…

29th July, 2022 in History , Maritime

How a shocking naval disaster nearly sank Winston Churchill

Just six weeks into the First World War, three British armoured cruisers, HMS Hogue, Aboukir and Cressy, patrolling in the southern North Sea, were sunk by a single German U-boat. The defeat made front page news across Europe. It was the biggest story from the war to date; it sho…

25th July, 2022 in History , Local & Family History

Re-enactment and research: How modern recreations can help us visualise the past

John Fletcher author of The Western Kingdom: The Birth of Cornwall discusses re-enactment and its relation to research and history. There is something extremely visceral, extremely real, about holding a sword. When you feel the weight of the blade and the rough leather of the gri…

16th June, 2022 in Entertainment , Society & Culture

Sex & Drugs and Rock & Roll: The music behind ‘The Microdot Gang’

Author of ‘The Microdot Gang’ James Wyllie, has put together the ultimate accompanying playlist to listen to while you read. An eclectic blend of rebellious punk, heavy acid rock, groovy blues, and booty-shaking drums, it’s got something for everyone. The complete playlist is ava…

13th April, 2022 in History

Polar regions today and yesterday

The ‘Heroic Age’ of Polar Exploration extended from the late 19th century until World War I, a period of about 20 years. In the North Polar region, as in the South, the ultimate goal was the pole itself. However, because the North Pole was a hypothetical location in the mids…

26th August, 2021 in Society & Culture , Women in History

Greenham Common Peace Camp in pictures

In 1981, a group of women marched from Cardiff to Greenham Common to protest American nuclear missiles on British soil. Greenham Common Peace Camp lasted for 19 years in one of the most successful examples of collective female activism since the suffragettes. Bridget Boudewijn vi…

17th March, 2021 in History , Women in History

A brief history of women in power

Historically, the most common way for a woman to become a ruler was as a regent. There were, however, many cases where the regent decided to stay in power. A prime example is Empress Wu Zetian who, as consort, ruled over China’s Tang Dynasty. She married Emperor Gaozong in 655; h…

16th March, 2021 in Society & Culture , Trivia & Gift

Ask the author: Yens Wahlgren on constructed languages

We spoke to Yens Wahlgren, author of The Universal Translator, about his love for constructed languages. You describe yourself as a xenosociolinguist, could you tell us what that means? Well, it’s a made up academic-sounding discipline for the study of how languages from outer sp…

4th November, 2020 in Society & Culture , Transport & Industry , Women in History

Married to a coal miner

Life was difficult for women from the coalfields during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Those girls who were daughters of miners understood some of the difficulties, but it was still their ambition to marry into the industry and take on the responsibility for looking after the…

2nd July, 2020 in History , Local & Family History

Stay Local, Shop Local

As I write this, as some shops re-open, it seems to me that the doom and gloom surrounding the future of the high street might be more complex than I thought. Let’s take a closer look. Nearly all traders apart from butchers, bakers and essentials have been shut for months. Grants…

26th February, 2020 in Biography & Memoir , History

Six things you (probably) didn’t know about Edward VI

Considering his desperation for a male heir, it’s rather ironic that it’s Henry VIII’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, we know best. His only legitimate son to survive infancy, Edward VI, became king at nine years old and died when he was only 15. Here are six things you migh…

13th December, 2019 in History , Trivia & Gift

Ask the authors: Historians on Christmas (and people) past

The festive season is upon us, and to celebrate we asked some of our authors about the figures from history they’d be interested in chatting to over Christmas dinner, and the Christmases past that most appeal to them… Which figure from history would you invite over for Christmas…

27th November, 2019 in Biography & Memoir , History

Why was Edward VIII’s abdication a necessity?

The conventional story of why Edward VIII came to abdicate in 1936 is well known and hardly needs any detailed rehearsal. The King abandoned the throne because he was determined on marrying the American divorcée Wallis Simpson, ‘the woman I love’, a union rejected by the politica…

Books related to this article

Victoria and Abdul (film tie-in)

Shrabani Basu ,

Through the Indian Mutiny

William Wright ,

The Prince and the Poisoner

Dan Morrison ,

In Spite of Oceans

Huma Qureshi ,

After the Raj

Hugh Purcell ,

Spying for the Raj

Jules Stewart , Sir Ranulph Fiennes (Foreword) ,

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up to our monthly newsletter for the latest updates on new titles, articles, special offers, events and giveaways.

© 2024 The History Press

Website by Bookswarm

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- AHR Interview

- History Unclassified

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Join the AHR Community

- About The American Historical Review

- About the American Historical Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

M iles T aylor . Empress: Queen Victoria and India .

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Chandrika Kaul, M iles T aylor . Empress: Queen Victoria and India ., The American Historical Review , Volume 125, Issue 3, June 2020, Pages 1086–1087, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhz1242

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Miles Taylor’s Empress illuminates the lengthy relationship, both professional and personal, between Queen Victoria (and Prince Consort Albert) and India. Based on a wide range of sources, Taylor also brings the story up to date with a final section on post-independence India and contemporary views on the British monarchy.

Taylor writes with panache and insight about both “an Indian Maharani” and a “British monarch,” but one who needs to be viewed, he argues, much more as a “dynastic imperial ruler of the long eighteenth century” rather than as a constitutional monarch in the nineteenth-century mold. While I find it difficult to agree with his claim that Victoria “has been silenced for too long” (7), it is certainly the case that in this book Taylor has put himself forward as her new champion.

Of the major royal figures associated with all things Indian and imperial, Victoria has always loomed large in both British and Indian consciousness, a fascination that can be said to have begun in earnest in the mid-nineteenth century. Many key elements of this saga are well known and have been extensively covered by a range of nineteenth- and twentieth-century commentators, as well as by later historians, art historians, and anthropologists. These include such landmark events as the Queen’s Proclamation in 1858 after the defeat of the Great Rebellion; her formal assumption of the title of Empress of India at the Delhi Durbar (masterminded by Prime Minister Disraeli) and the related tour of her son, the Prince of Wales, to the subcontinent in 1876–1877; successive visits in the early twentieth century, including the Prince of Wales’s tour in 1905, his later tour as King George V in 1911, and the in-depth tour by her grandson Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) in 1921–1922; the imperial and Indian exhibitions in Britain, beginning with the Great Exhibition in 1851; Victoria’s extensive architectural renovations, such as the creation of the Indian Durbar room in Osborne House; her significant relations with Indian princes, including the exiled Prince Duleep Singh, as well as with her Indian servants and tutors who taught her rudimentary “Hindustani.” In writing about these, Taylor acknowledges his debt to other authors.

What Taylor succeeds in doing for the first time is casting a much wider net and offering a comprehensive chronological narrative, as well as illuminating the underappreciated aspects of the story. Taylor successfully analyzes the impact of India on the Queen and “the influence of the queen over Indian political and cultural life” (6). The three themes that he interweaves in this narrative include “the agency of the queen,” the “uses” to which the Raj “put the name and fame of the queen,” and finally “the diffusion of representations of Queen Victoria in Indian political culture” (7–9).

There is an established tradition of academic research on, as well as a seemingly insatiable popular fascination with, the cultural dimensions of monarchical influence and imperial propaganda. (Television documentaries and docudramas on Victoria and her heirs and spares continue unabated on our screens.) In his chapter titled “Exhibiting India,” Taylor expands on the role of Prince Albert and notes how his knowledge of India was “rooted” in a German tradition (49). It was Albert’s presiding “genius” that resulted in the “most extensive display of Indian culture ever seen in Britain” as part of the Great Exhibition (53).

Victoria never set foot in India, but she followed the travels—all carefully choreographed—of her children with a mixture of envy and worry, and she delighted in the rich presents they brought back for her. One of her sons, the Duke of Connaught, even served in India. “No one was keener on the title Empress of India than the queen” (168). Taylor underlines Victoria’s abiding interest in the politics of empire but explains how and why this was circumscribed and limited, a position brought home forcefully when he recounts how she was unable to prevent the execution of a reigning prince of Manipur in 1891. In the chapter “Mother of India,” Taylor provides a fascinating insight into how the Empress, and the Duke of Connaught and his wife, took a keen interest in the role and condition of women, including in their education and professional training. Victoria became “an unlikely role model for a diverse range of women and women’s organisations” in late nineteenth-century India (192). Yet this contrasted sharply with Victoria’s views at home, including her antisuffragist stance and dislike of widow remarriage.

By the time of her death, he concludes, Victoria was “celebrated as an Indian monarch as much as a monarch of India” (248). In Empress, Taylor has achieved that enviable balance between academic rigor and popular appeal, and this book will remain the standard work on Victoria and the Raj for many years to come.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1937-5239

- Print ISSN 0002-8762

- Copyright © 2024 The American Historical Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Eating And Health

- Food For Thought

- For Foodies

Food History & Culture

Queen victoria's unlikely bond with indian attendant made curry classy.

Nina Martyris

In the last 13 years of Queen Victoria's life, she spent a great deal of time with Abdul Karim, who came from India initially to wait on the queen's table, but soon became part of her inner circle. And despite all opposition, Victoria and Karim curried on. Alexander Bassano/Spencer Arnold/Getty Images hide caption

In the last 13 years of Queen Victoria's life, she spent a great deal of time with Abdul Karim, who came from India initially to wait on the queen's table, but soon became part of her inner circle. And despite all opposition, Victoria and Karim curried on.

They met at breakfast. On the third morning of her Golden Jubilee celebrations in June 1887, a tired Queen Victoria was greeted by a tall, bearded young man in a scarlet tunic and white turban. Victoria was 68, Abdul Karim, 23. As he knelt to kiss her feet, she was struck by what she described in her diary as his "fine serious countenance." Some inexplicable connection was made that day, with the queen, who was still grieving the death of her beloved Scottish servant and companion John Brown, deeply drawn to Karim.

It was the start of an extraordinary friendship — and the theme of a syrupy new film. Victoria & Abdul is a nostalgic colonial romp redeemed mainly by Judi Dench's stirring performance as an obstinate old lioness, but it shines the spotlight on this highly unconventional relationship that dominated the lonely queen's final years and broke the boundaries of race, class and religion in an era defined by these hierarchies .

Karim had been sent from Agra to London as a "gift from India," to wait at the queen's table. But Victoria was so taken by the young Muslim man that she asked him to teach her Urdu (then called Hindustani). Within a year, he had gone from being what the English dismissively referred to as the "kitchen boy" to the queen's "Munshi" (teacher).

From India To North Korea, Via Japan: Curry's Global Journey

Over the next 13 years, until the queen's death in 1901, Karim was constantly at her side, even spending a night alone with her in her cottage in the Scottish Highlands, where she and Brown had passed the time together. Karim was viewed as the late Brown's replacement — snidely referred to in the movie as "the brown John Brown" — and his closeness to the queen, though her feelings were clearly maternal, scandalized the royal household.

But a spicier outcome of this friendship was the elevation of a dish already popular in England: curry.

A few weeks after kissing her feet, writes Shrabani Basu in Victoria & Abdul: The True Story of the Queen's Closest Confidant (the book on which the movie is based), Karim cooked Victoria "a fine Indian meal: chicken curry, daal , and a fragrant pilau ." In a diary entry on Aug. 20, 1887, the queen noted appreciatively: "Had some excellent curry prepared by one of my Indian servants."

This was scarcely the first time Victoria had tasted curry, a dish which had become popular in England in the late Georgian period, with a variety of curry pastes and powders available in the stores. "She definitely had curry before Karim," says British food historian Annie Gray, who chronicled Victoria's lavish appetite in her book, The Greedy Queen: Eating with Victoria . "Long before Karim, curry de poulet appeared on the dinner menu at Windsor Castle on December 29, 1847."

Victoria & Abdul

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

But, as Gray points out, the curries Victoria ate in her youth were quite different from the one Karim cooked her. "Those early curries, which I call Raj or Anglo-Indian curries, were not what we would recognize today," she says. "They used fruit, were heavy on turmeric and galangal, and were creamy and mild. I once cooked a Raj-style curry and it started off with frying cucumber and apple — and I thought, really? But if you take it on its own merit, it's really nice if still slightly bonkers. In any case, in Victorian England, curry was a way to use up leftover meat and vegetables. It was not regarded as a high-class food."

The queen evidently thought otherwise. Soon, curry was being served on a regular basis at her dining table. Victoria's Swiss cook, Gabriel Tschumi, who joined the kitchens as an apprentice in 1898, described how the Indians did everything from scratch, using only halal meat and grinding their own spices: "For religious reasons, they could not use the meat which came to the kitchen in the ordinary way, and so they killed their own sheep and poultry for the curries. Nor would they use the curry powder in stock in the kitchens, though it was of the best imported kind, so a part of the household had to be given to them for their special use, and there they worked Indian-style, grinding their own curry powder between two large round stones and preparing all their own flavoring and spices."

In the late 1880s, says Gray, curries feature on Victoria's menus twice a week — as a lunch dish (chicken curry) on Sundays and as a dinner dish (fish curry) on Tuesdays. "Curries were referred to as the 'Indian dish,'" says Gray. "There were two high-ranking tables – the household table and the queen's table. The 'Indian dish' would only appear on the queen's table." Tschumi claimed it was served "each day at luncheon whether the guests partook of it or not," but Gray disputes this, pointing out that the surviving ledgers make no mention of curry for lunch every day.

Indeed, there's no real evidence of Victoria actually relishing it. The only time curry pops up in her diary is on that very first occasion when Karim makes it for her. "She never mentions it again," says Gray, who strongly suspects that this legendary curry wasn't even cooked by Karim, but by the Indian cook whom he and the other four Indian servants had employed to cook for them.

"There are all these myths about Victoria eating curry every day and for breakfast, which is just not true," says Gray . "Her breakfast was mutton chops, sausages and a beef steak. She had a sweet tooth, a taste for whiskey (once adding it to her claret), and a lifelong penchant for Brussels biscuits (a kind of rusk) and fresh fruit. Her physician, Dr. Reid, was forever advising her to eat less and take digestion salts to deal with her stomach upsets and flatulence, but no, though she ordered curry to be cooked, she didn't eat it every day."

As curries simmered in the royal kitchens, so did the royal household, which watched with growing resentment as the lowborn Indian servant continued to bask in the queen's favor, receive land grants, promotions and honors, and walk around with a sword and a chest of medals. "He had reduced the household to a level of abject jealousy," says Gray. Everyone, including the Indian servants, found him pompous, grasping, and conceited.

But the queen wouldn't hear a word against him. She dismissed all complaints as "race prejudice" and was furious when she found out that her Indian servants were being called "the Black Brigade." In her eyes, the "gentle and understanding" Karim was the one sinned against. In the teeth of all opposition — including from Dr. Reid and her son and heir Edward — she robustly defended the "unfortunate persecuted Munshi."

Through the plotting and intrigue, the queen carried on with her Urdu lessons. A quick learner, she filled her little red and gold phrase book with everyday Urdu phrases, including two peevish complaints about her meals: Cha Osborne mein hamesha kharab hai (The tea is always bad at Osborne) and Unda thik ubla nahin hai (The egg is not properly boiled.)

Karim, whose English had greatly improved, regaled her with spangled stories of the Taj Mahal, the street bazaars of Agra, and the way in which religious festivals were celebrated in his homeland. Victoria had been proclaimed Empress of India in 1876, but had never visited the country. For the gourmand queen, tasting an Indian mango soon became an idée fixe. The mango scene in the film, says Basu, is based on fact. Victoria did indeed order a mango from India, despite Karim warning her it wouldn't survive the six-week sea voyage. Sure enough, when it arrives and is presented by a footman, the overripe orb is peremptorily declared to be "off."

"Victoria was an adventurous eater," says Gray, "She ate anything – Indian, Chinese (she loved the bird's nest soup), new fruits, curry. My grandmother, for instance, thought curry was this funny foreign stuff, she wouldn't eat it. Victoria, living a hundred years ago, did. I don't think she popularized curry per se, it was already so popular, but her embracing of Indian culture, including its food, helped make it ahead of its time."

By her Diamond Jubilee in 1897, the queen was deep in the throes of what her exasperated doctor called "Munshi mania." She was implacable — even the news that he had gonorrhea did nothing to dent her affection for him. But as Victoria's reign drew to a close, so did Karim's. Barely hours after the queen's funeral, the new monarch, Edward VII, evicted the Munshi and ordered he be deported to India.

"The new king did not want to see any more turbans in the palaces or smell the curries from the Royal kitchens," writes Basu.

It was too late of course. Curry has insinuated itself into the English palace and palate. The Swiss chef who wrote about the Indian servants grinding masalas would later note that under Edward VII, curry and rice were cooked regularly by non-Indian cooks, and that George V, Edward's curryholic son and Victoria's grandson, insisted on curry every single day.

Nina Martyris is a journalist based in Knoxville, Tenn.

- food history

- Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria’s proclamation as Empress of India

While Queen Victoria was the Queen of the United Kingdom, she also held the additional title of (the first) Empress of India. She was proclaimed as Empress on 1 May 1876 and held the title until her death on 22 January 1901. In total, she served as India’s empress for 24 years, eight months, and three weeks.

The idea of the Queen becoming Empress of India had been discussed for decades before it was instituted, first being brought up in 1843. Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar had been deposed in 1857 at which point control of British India was transferred to the Crown from the East India Company (EIC). Victoria was offered the position of empress after the EIC was dissolved; she accepted it on 1 May 1876 with it being officially proclaimed in India on 1 January 1877.

Obtaining the title of Empress of India, came 15 years after her beloved husband, Prince Albert had died. As such, Victoria had no consort while reigning over India.

Victoria did not have much power over the Indian government, serving more as a figurehead. Instead, the Governor General stood in her stead in India where he presided over legislative branches at the federal and provincial levels.

One significant difference in Victoria’s reign over India from the United Kingdom was religion. Whereas in the United Kindom, the Church of England reigned supreme with the Queen as the head of the church, in India this did not apply. Most Indians followed the Hindu religion, and this eliminated the power of the Church of England in the country. Victoria was adamant that freedom of religion be observed in the country having respect for Indians and their various beliefs. The lack of religious freedom threatened to undermine the “native religions and customs,” she said.

Empress Victoria threatened to abdicate several times as she wanted the UK (under the leadership of Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli) to fight against Russia in the Russo-Turkish War. The threats were just that, threats, as Victoria never made good on her ultimatum.

While as Queen of the United Kingdom she was referred to as Her Majesty, as Empress of India, she was called Her Imperial Majesty. And subsequent emperors were known as His Imperial Majesty until 22 June 1948 when King George VI relinquished the title after the Second World War. India had gained its independence a year earlier.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- british royal family

- Empress of India

- Queen Victoria

- The Royal Women

- the year of queen victoria

- Victoria 200

Be the first to comment

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Yes, add me to your mailing list

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Copyright © 2024 | MH Magazine WordPress Theme by MH Themes

To provide the best experiences, we and our partners use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us and our partners to process personal data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site and show (non-) personalized ads. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Click below to consent to the above or make granular choices. Your choices will be applied to this site only. You can change your settings at any time, including withdrawing your consent, by using the toggles on the Cookie Policy, or by clicking on the manage consent button at the bottom of the screen.

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter and stay up to date on History of Royal Women's articles!

Not interested? Simply click 'close' in the top right corner to continue reading!

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

2 January 1877: Queen Victoria proclaimed Empress of India

The Guardian reports on the elevation of Victoria from Queen to Empress.

- National newspapers

- Guardian 190

- Queen Victoria

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Queen Victoria becomes the Empress of India

George p. landow, editor-in-chief, the victorian web.

[ Victorian Web Home —> Political History —> Social History —> Queen Victoria —> Next ]

The Imperial Assembly at Delhi: The Chief Herald [Major Barnes] Reading the Proclamation . . Artist: Lieutenant C. Pulley, of the 3rd Ghoorkahs. Source: Internet Archive web version of The Illustrated London News (10 February 1877): 137 [Click on images to enlarge them.]

s Robert Blake explains in his biography of Benjamin Disraeli, “proposals to adopt the imperial title for India had been in the air ever since the Mutiny . The plan can only be understood if the traumatic nature of that disaster is remembered” (539). In addition to creating what Blake terms a “lasting apprehension about the stability of British rule,” the 1857 mutiny made British rule seem especially vulnerable to Russia’s advance into central Asia. Since the “the Tsar was an Emperor,” Victoria, the head of the country opposing him in Asia, should be an empress. In other words, as Blake puts it, “Basically the Royal Titles Bill, like the Prince’s visit [to India], was a counter-blast to the threat of Russian invasion or subversion in India, a measure designed to reaffirm and symbolize British power” (540).

According to Blake, the bill granting Victoria the title of empress “was a case of Disraeli’s yielding to the Queen. Not that he disapproved of the contents, for he was all in favour of her becoming Empress of India; but the timing was inconvenient and he would have postponed it if he could. He did not wish, however, to cross his ‘Royal Mistress’, who had set her heart on the idea” (540)

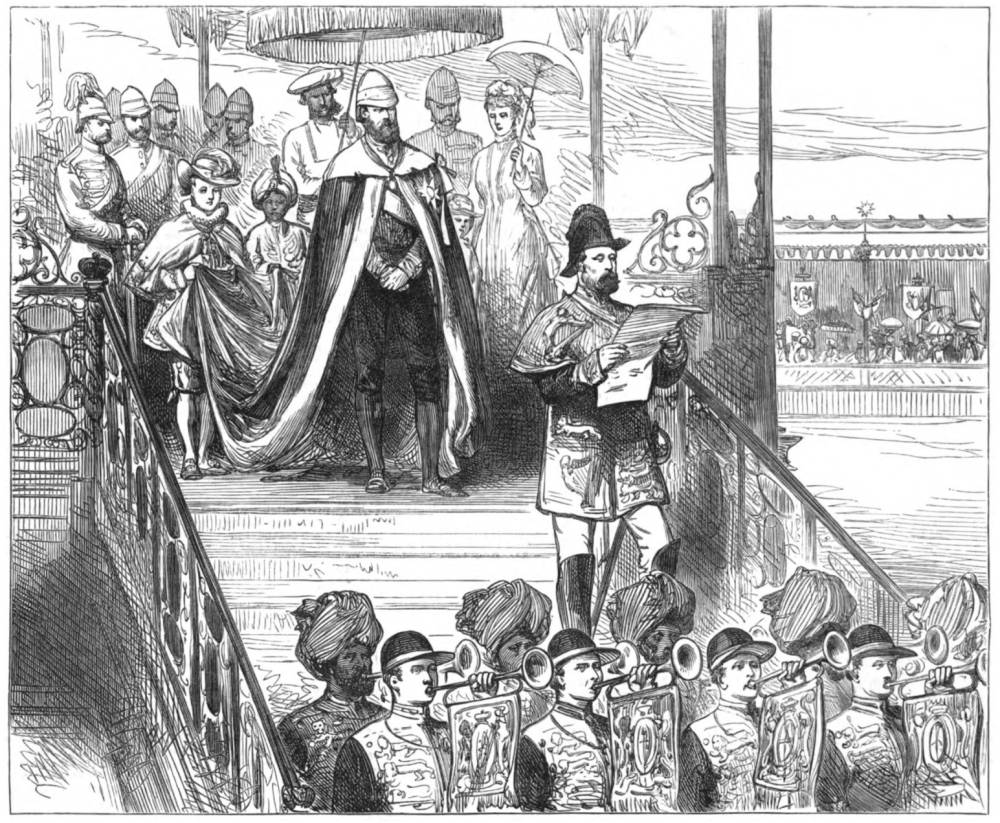

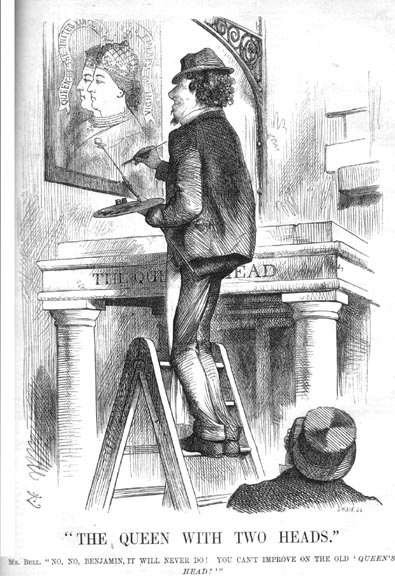

Three Punch cartoons by John Tenniel: Left: The Queen with Two Heads . middle: Empress and Earl . Right: New Crowns for Old Ones . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Return of the Wanderer. His Wonder . The cartoonist in Fun depicts thr Prince’s shock on discovering his mother is now Empress of India.

The Queen and her Prime Minister were both surprised by the hostility to the idea “excited both in London society and in the Liberal Press, quarters seldom in harmony,” and part of the reason for the opposition lay with Disraeli, who made two blunders, the first of which was failing to “inform the Opposition in advance, as was the normal convention with regard to such legislation.” Secondly, Disraeli also “forgot to tell the Prince of Wales, who, returning from his tour, was understandably cross when he learned for the first time from the newspapers that he would one day be Emperor of India” (540). Although Queen Victoria “took the blame for both these omissions,” Disraeli nonetheless had a far more difficult time passing the bill than would have otherwise been necessary.

For all the fodder it provided for The Illustrated London News and cartoonists like John Tenniel, “whether it made any difference to the average Indian is very doubtful.”

Related material

- Disraeli’s speech on the Royal Titles Bill, 9 March 1876

Bibliography

Blake, Robert. Disraeli . New York: Anchor, 1968.

Last modified 30 December 2011

How Queen Victoria remade the British monarchy

She took the throne amid calls to replace the royals with a republic. but queen victoria held power through ambitious reforms and imperialist policies, and her legacy endures today..

n the 1800s, Queen Victoria oversaw the expansion of the British Empire—which would cover a fifth of the Earth's surface by the end of the century—and critical reforms to the monarchy.

The Famine Queen. The Widow of Windsor. Grandmother of Europe. Queen Vic. In the 19th century, Queen Victoria earned all those nicknames and more—testaments to the enduring influence of her 64-year (1837-1901) reign over the United Kingdom.

During the period now known as the Victorian Era, she oversaw her nation’s industrial, social, and territorial expansion and gained a reputation as a trendsetter who made over European attitudes toward the monarchy. An estimated one in four people on Earth were subjects of the British Empire by the end of her rule. But when Victoria took the throne, the British monarchy was deeply unpopular.

Ascension to the throne

Victoria was the product of a succession crisis in England’s royal family that occurred when Princess Charlotte, the presumptive successor to King George, and her infant son died in childbirth. Charlotte’s brothers—all of whom were single and had given the monarchy a bad name with their profligate spending and messy personal lives—raced to produce an heir. One of those brothers, Edward, hastily married a widowed German princess and became the first to produce an heir. Born in 1819, Alexandrina Victoria was a direct successor to the crown.

Palace intrigue made for a miserable childhood. Victoria’s father died when she was a child, and her ambitious mother allied herself with the scheming Sir John Conroy, a member of the royal household who seized the chance to gain power and influence through the future queen. He created what became known as “the Kensington system,” an elaborate set of rules that isolated the young princess at Kensington Palace and put him in control of her education and upbringing. Designed to keep Victoria dependent and loyal to Conroy and her mother, the system resulted in an unhappy childhood—and a growing sense of resentment.

Victoria broke free in 1837, when she turned 18 and rose to the throne. As soon as she became queen, she banned Conroy from her court and marginalised her mother. In 1840, she married her cousin Albert, a German prince. It was a genuine love match—she wrote that her wedding night was “bliss beyond belief”—and they went on to have nine children.

Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert were patrons of the arts—including the burgeoning field of photography. They commissioned images to document life at the palace and even reenacted their wedding for a photograph in 1854.

Early reign

During her early reign, Victoria was heavily influenced by Lord Melbourne, the prime minister, and Albert, who was her closest political advisor and whom some historians believe was “king in all but name.” Together, they pursued an agenda of modernisation and stability in an era of political upheaval. The monarchy’s reputation had been badly damaged by Victoria’s predecessors, and the British populace clamoured to replace the monarchy with a republic. And in Ireland, the potato famine between 1845 and 1852 fomented outright rebellion.

Together with her husband, Victoria faced those challenges head-on, working to strengthen the position of the monarchy in England and throughout Europe, where there was also a growing distaste for royals who expected the public to foot the bill for their lavish lifestyles. In contrast, Victoria expanded the monarch’s public role, supporting charities, the arts, and civic reform to counter the view that British royalty wasn’t worth the expense. As a result, the queen and her growing family became beloved celebrities and influenced popular culture, introducing England to everything from white wedding dresses to Christmas trees .

In 1861, tragedy struck when Albert died at 42. Victoria was devastated and went into deep mourning. She wore black for the rest of her life and withdrew from the public eye for years. The republican movement grew during her isolation, and she was criticised for her absence from public life.

Discover the luminous history of London's Royal Albert Hall.

Later years

Victoria resumed her public duties by the late 1860s. Her later reign was largely devoted to encouraging peace in Europe and expanding and consolidating her massive political empire. She became Empress of India in 1877 and influenced foreign relations closer to home through her children and grandchildren, many of whom married into European royalty.

At the beginning of her monarchy, Britain was seen largely as a trading power. But under Victoria, it became a mighty empire and the world’s most powerful nation. Over the course of the 19 th century, it grew by 10 million square miles and 400 million people. Those gains came at a tremendous price: England was almost constantly at war during Victoria’s reign, and the colonialism practiced in her name involved brutal subjugation.

Though Victoria was popular, her subjects still pushed to reform the monarchy. Ultimately, this led to an erosion of the monarch’s direct political power as ordinary British people gained the vote, the secret ballot, and other political reforms in the mid- to late 1800s.

By her death in 1901, Victoria was an institution, known for her willpower and the vast empire she ruled. The British Empire covered a full fifth of the Earth’s surface and had become the preeminent superpower of its day.

Victoria’s attempts to bolster European monarchies by marrying off her family members achieved short-term peace, but they sowed the seeds of some of the 20th century’s most destructive conflicts. By the onset of World War I in 1914, her grandchildren would turn against each other.

Although the relentless colonialism of the empire she ruled and the devastating war she inadvertently helped seed now cast a shadow over Victoria’s reign, she believed British power and prosperity were paramount. As she wrote in 1899, “We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat; they do not exist.” For a woman born to rule, there was no room for doubt as to her historic destiny—or the might of the empire built in her name.

- Imperialism

- Governments

- People and Culture

- United Kingdom

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Below is a list of foreign visits made by Queen Victoria during her reign (which lasted from 1837 until 1901), giving the names of the places she stayed and any known reasons for her visit.. Despite being head of the British Empire, which included territory on all inhabited continents, Queen Victoria never travelled outside of Europe, only travelling as far north as Golspie, southwesterly as ...

Published: January 22, 2021 at 7:40 AM. On 1 January 1877, while Queen Victoria was quietly celebrating the new year with her family at Windsor Castle, a spectacular celebration was taking place more than 4,000 miles away in Delhi, India, to mark the Queen's new imperial role as Empress of India. Determined to flaunt the power and majesty of ...

Mohammed Abdul Karim CVO CIE (1863 — 20 April 1909), also known as "the Munshi", was an Indian attendant of Queen Victoria.He served her during the final fourteen years of her reign, gaining her maternal affection over that time. Karim was born the son of a hospital assistant at Lalitpur, near Jhansi in British India.In 1887, the year of Victoria's Golden Jubilee, Karim was one of two ...