- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

How fast are the Voyager spacecrafts travelling?

NASA's Voyage probes are speeding their way around the Solar System.

Keiron Allen

Asked by: Anonymous

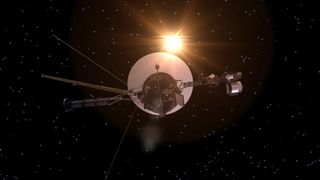

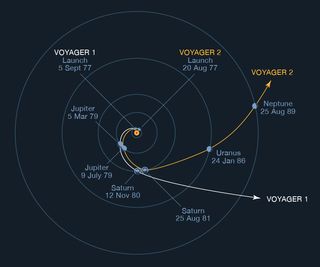

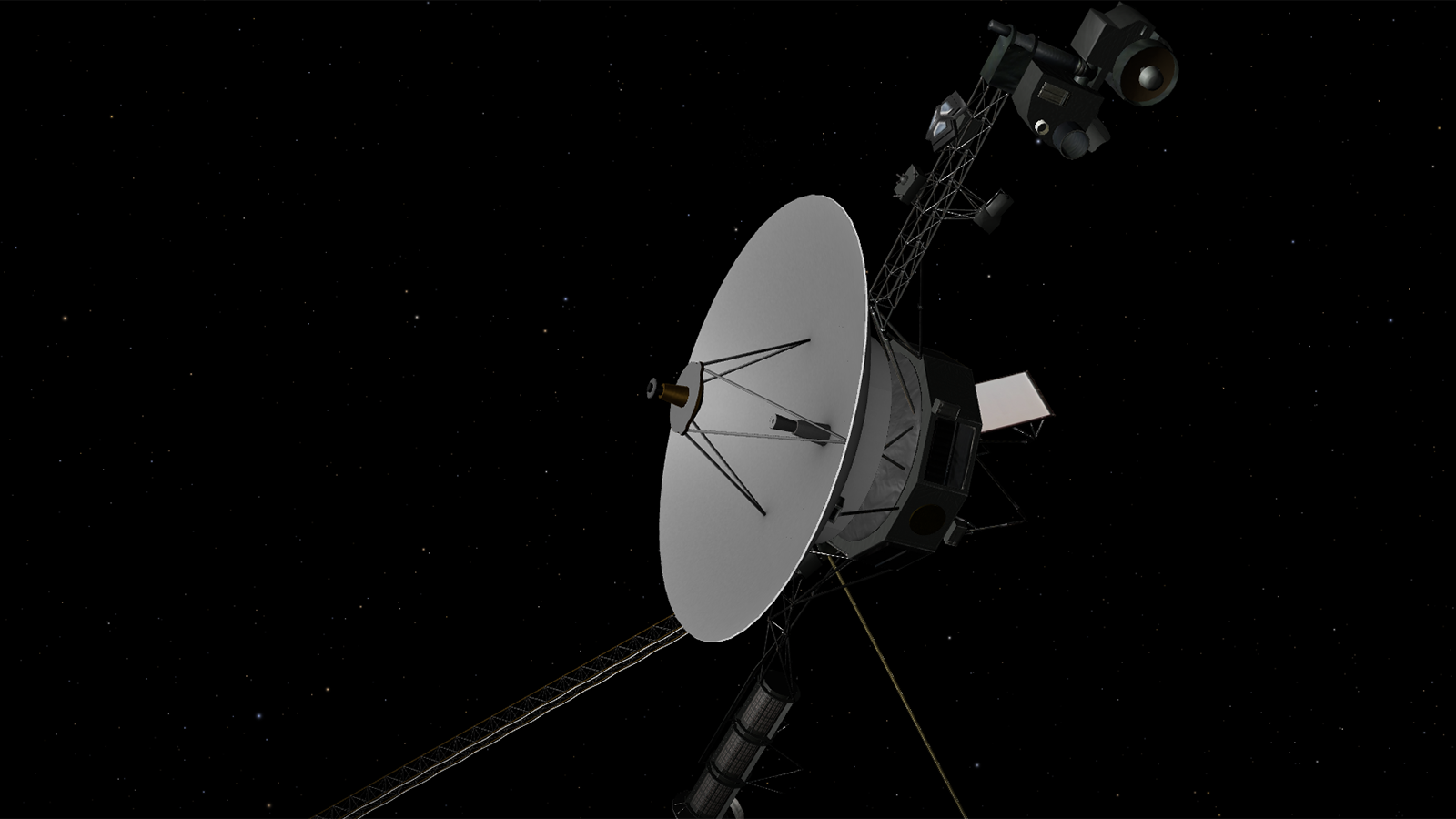

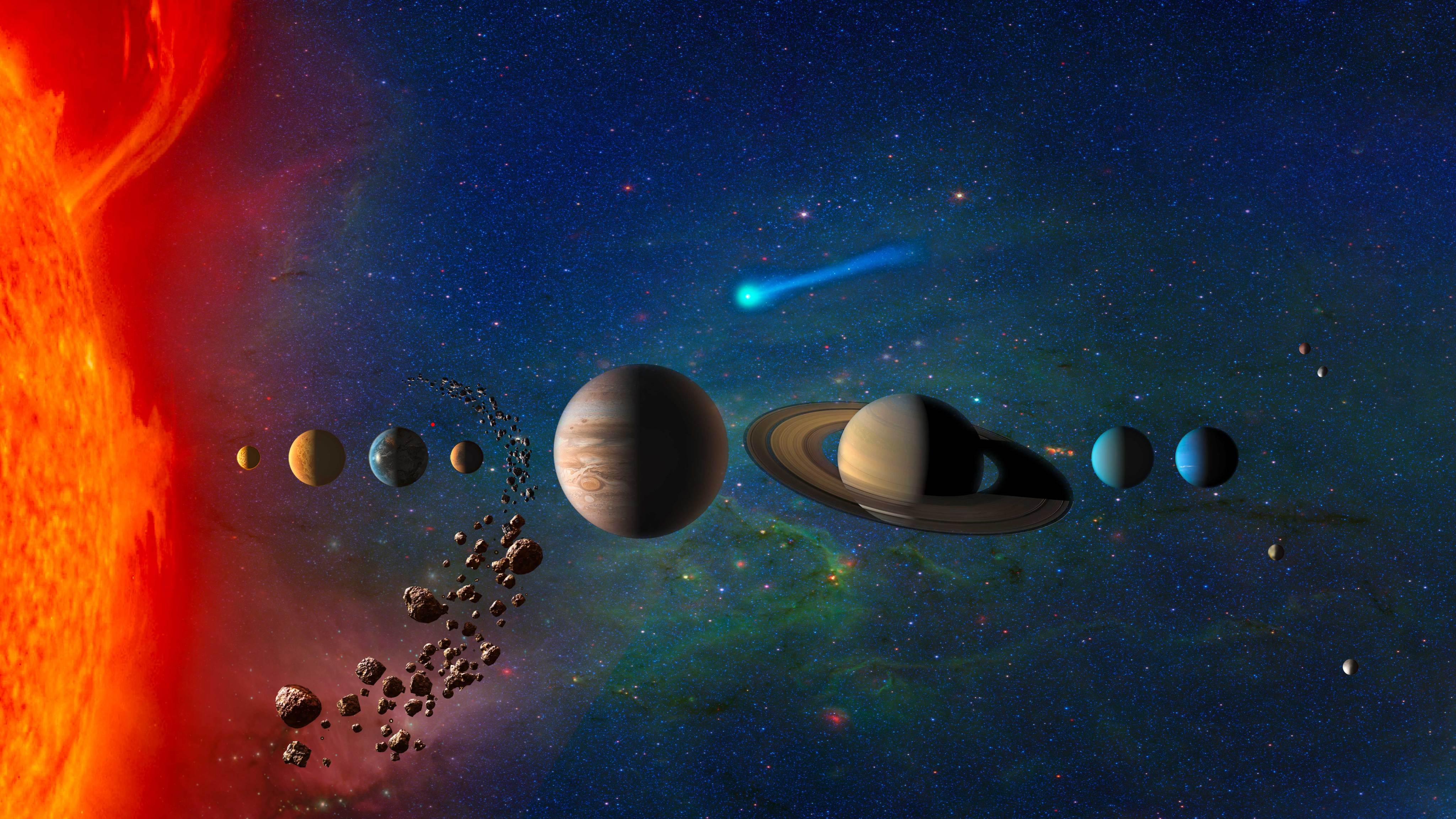

Launched in 1977, NASA’s two Voyager probes surveyed Jupiter and Saturn, with Voyager 2 also visiting Uranus and Neptune before heading out of the Solar System. Voyager 1 has since become the fastest and most distant man-made object in the Universe, travelling at around 61,500km/h at a distance of 17.6 billion km from the Earth. Perhaps most incredible of all, NASA is still in communication with it, despite radio signals taking 16 hours to reach it.

Subscribe to BBC Focus magazine for fascinating new Q&As every month and follow @sciencefocusQA on Twitter for your daily dose of fun science facts.

Share this article

Food writer

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

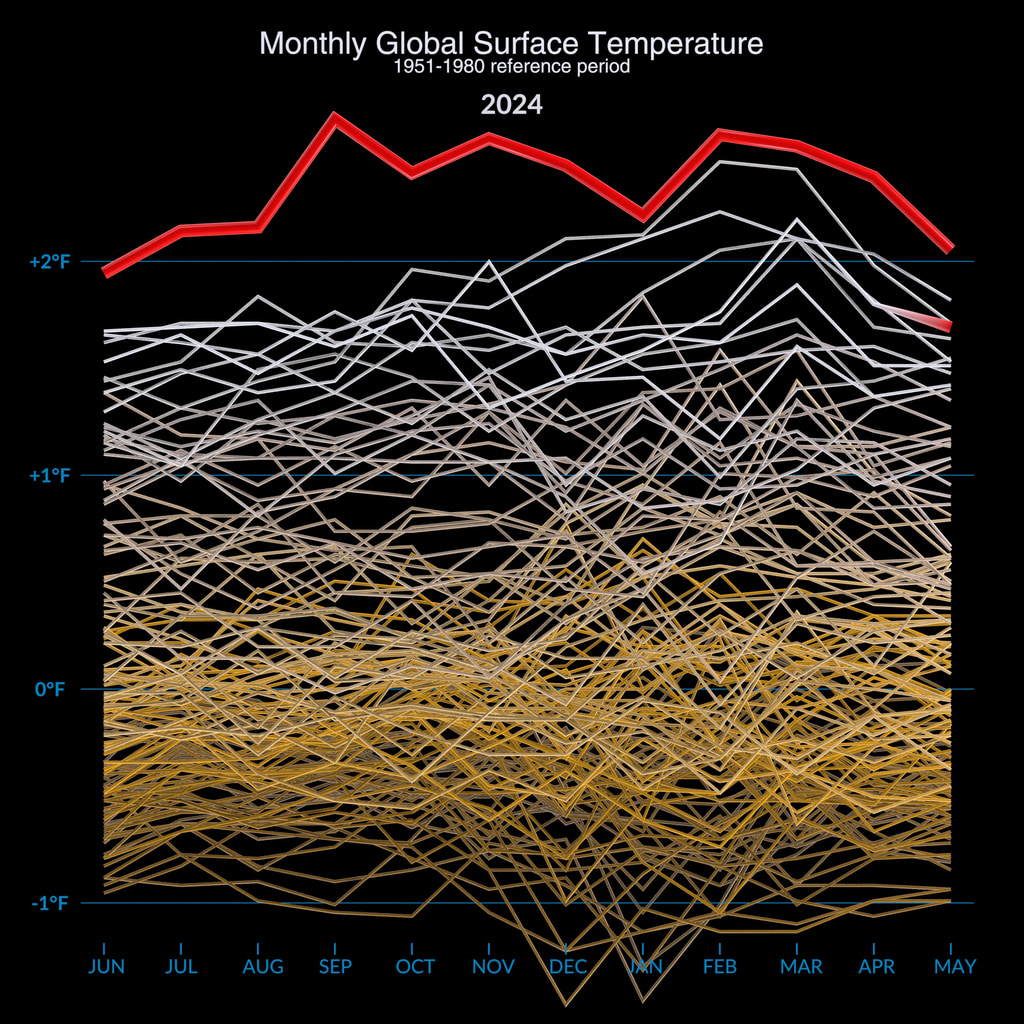

NASA Analysis Confirms a Year of Monthly Temperature Records

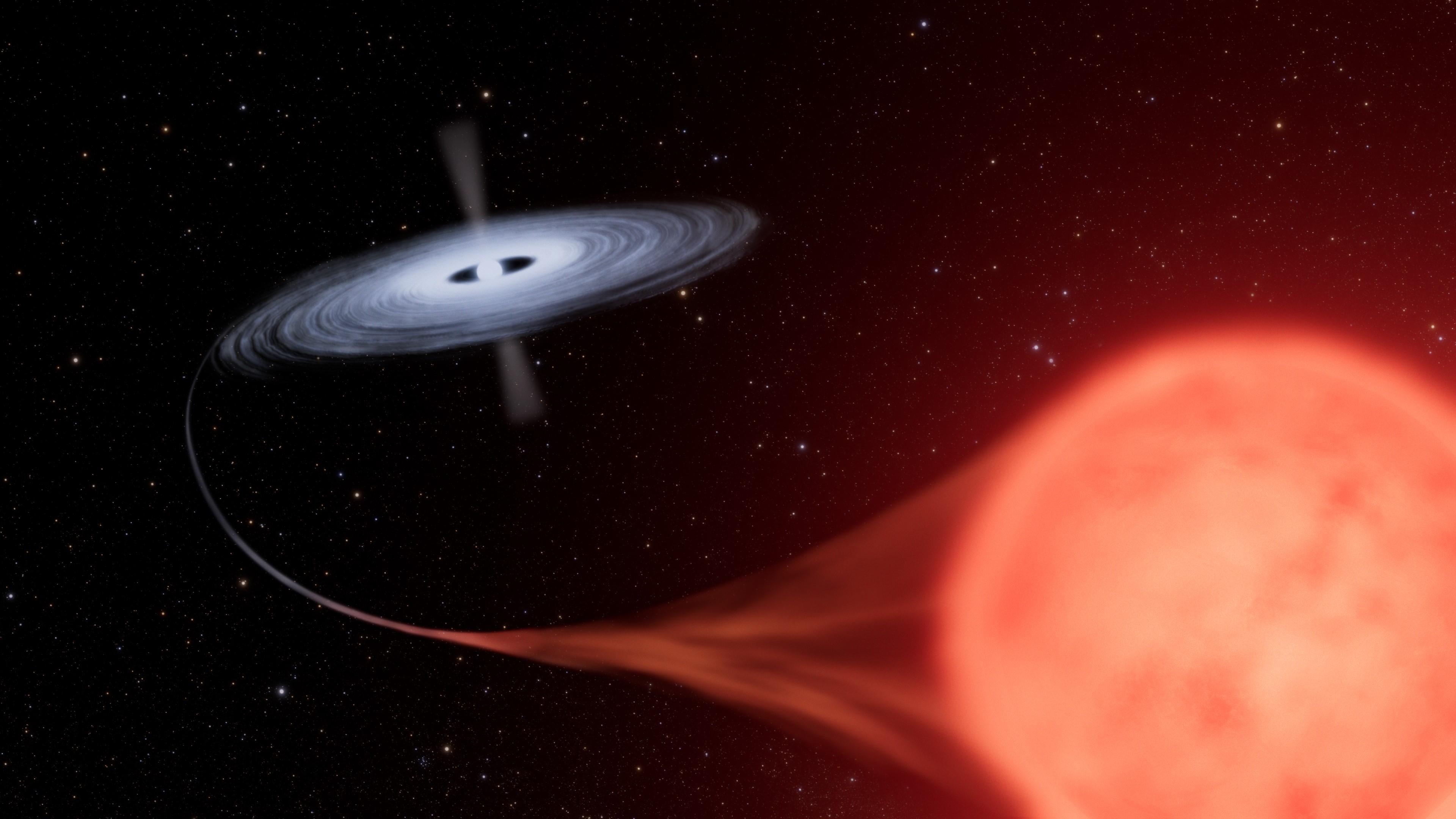

Hubble Finds Surprises Around a Star That Erupted 40 Years Ago

Nasa watches mars light up during epic solar storm.

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

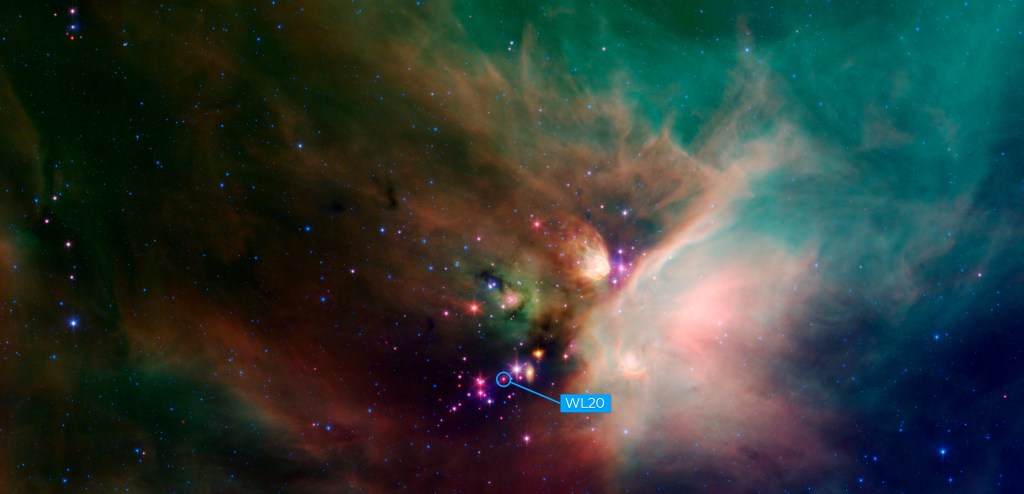

NASA’s Webb Reveals Long-Studied Star Is Actually Twins

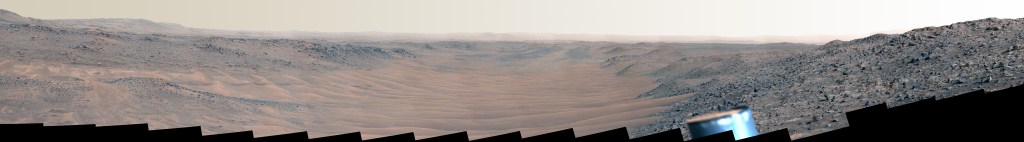

NASA’s Perseverance Fords an Ancient River to Reach Science Target

Apollo 1 Resources

Lakita Lowe: Leading Space Commercialization Innovations and Fostering STEM Engagement

NASA’s Repository Supports Research of Commercial Astronaut Health

NASA Astronauts Practice Next Giant Leap for Artemis

NASA Announces New System to Aid Disaster Response

Amendment 21: A.3 Ocean Biology and Biogeochemistry: NSPIRES cover page issue and Delay of Proposal Due Date

Ed Stone, Former Director of JPL, Voyager Project Scientist, Dies

Coming in Hot — NASA’s Chandra Checks Habitability of Exoplanets

NASA’s Roman Mission Gets Cosmic ‘Sneak Peek’ From Supercomputers

Research Programs

Flight Programs

ARMD Solicitations

Winners Announced in Gateways to Blue Skies Aeronautics Competition

NASA, Industry to Start Designing More Sustainable Jet Engine Core

Food Safety Program for Space Has Taken Over on Earth

Artemis Generation Shines During NASA’s 2024 Lunabotics Challenge

NASA Wallops to Support Sounding Rocket Launch

From Psychology to Space: Alexandra Whitmire’s Journey and Impact in NASA’s Human Research Program

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

Astronauta de la NASA Marcos Berríos

Resultados científicos revolucionarios en la estación espacial de 2023

Nasa’s voyager spacecraft still reaching for the stars after 40 years.

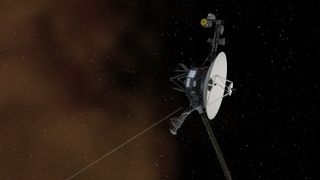

Humanity’s farthest and longest-lived spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, achieve 40 years of operation and exploration this August and September. Despite their vast distance, they continue to communicate with NASA daily, still probing the final frontier.

Their story has not only impacted generations of current and future scientists and engineers, but also Earth’s culture, including film, art and music. Each spacecraft carries a Golden Record of Earth sounds, pictures and messages. Since the spacecraft could last billions of years, these circular time capsules could one day be the only traces of human civilization.

“I believe that few missions can ever match the achievements of the Voyager spacecraft during their four decades of exploration,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) at NASA Headquarters. “They have educated us to the unknown wonders of the universe and truly inspired humanity to continue to explore our solar system and beyond.”

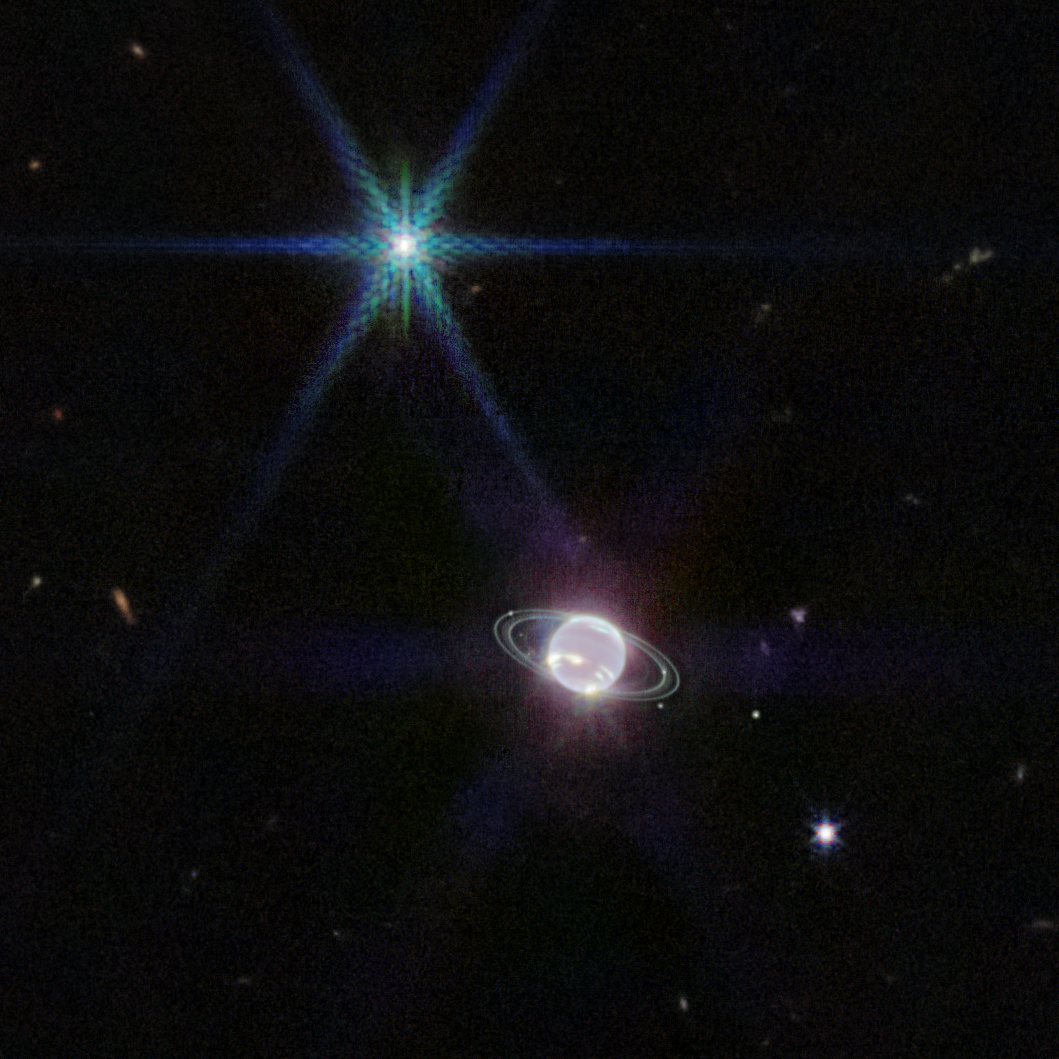

The Voyagers have set numerous records in their unparalleled journeys. In 2012, Voyager 1, which launched on Sept. 5, 1977, became the only spacecraft to have entered interstellar space . Voyager 2, launched on Aug. 20, 1977, is the only spacecraft to have flown by all four outer planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Their numerous planetary encounters include discovering the first active volcanoes beyond Earth, on Jupiter’s moon Io ; hints of a subsurface ocean on Jupiter’s moon Europa ; the most Earth-like atmosphere in the solar system, on Saturn’s moon Titan ; the jumbled-up, icy moon Miranda at Uranus; and icy-cold geysers on Neptune’s moon Triton .

Though the spacecraft have left the planets far behind – and neither will come remotely close to another star for 40,000 years – the two probes still send back observations about conditions where our Sun’s influence diminishes and interstellar space begins.

Voyager 1, now almost 13 billion miles from Earth, travels through interstellar space northward out of the plane of the planets. The probe has informed researchers that cosmic rays, atomic nuclei accelerated to nearly the speed of light, are as much as four times more abundant in interstellar space than in the vicinity of Earth. This means the heliosphere, the bubble-like volume containing our solar system’s planets and solar wind, effectively acts as a radiation shield for the planets. Voyager 1 also hinted that the magnetic field of the local interstellar medium is wrapped around the heliosphere.

Voyager 2, now almost 11 billion miles from Earth, travels south and is expected to enter interstellar space in the next few years. The different locations of the two Voyagers allow scientists to compare right now two regions of space where the heliosphere interacts with the surrounding interstellar medium using instruments that measure charged particles, magnetic fields, low-frequency radio waves and solar wind plasma. Once Voyager 2 crosses into the interstellar medium, they will also be able to sample the medium from two different locations simultaneously.

“None of us knew, when we launched 40 years ago, that anything would still be working, and continuing on this pioneering journey,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at Caltech in Pasadena, California. “The most exciting thing they find in the next five years is likely to be something that we didn’t know was out there to be discovered.”

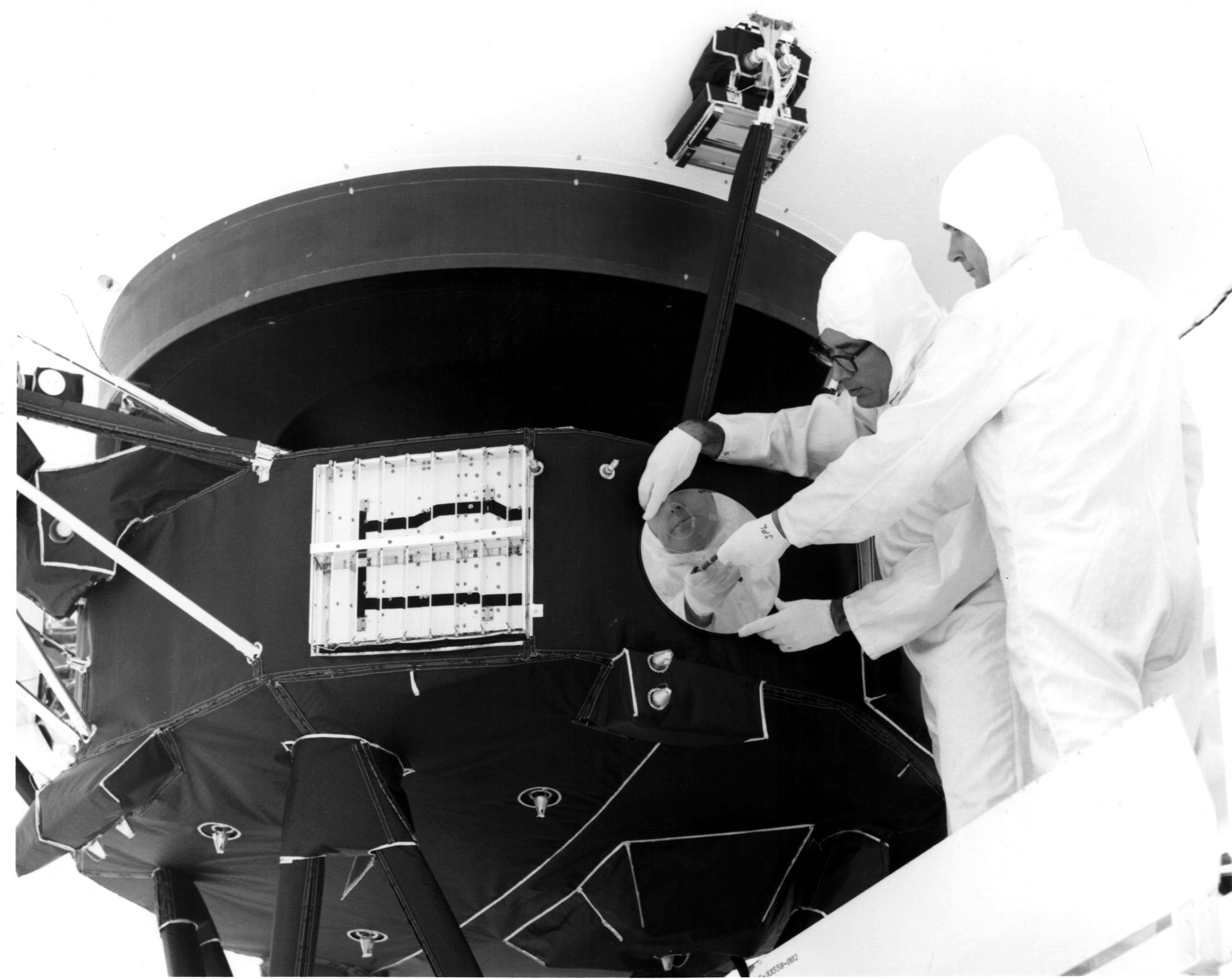

The twin Voyagers have been cosmic overachievers, thanks to the foresight of mission designers. By preparing for the radiation environment at Jupiter, the harshest of all planets in our solar system, the spacecraft were well equipped for their subsequent journeys. Both Voyagers are equipped with long-lasting power supplies, as well as redundant systems that allow the spacecraft to switch to backup systems autonomously when necessary. Each Voyager carries three radioisotope thermoelectric generators, devices that use the heat energy generated from the decay of plutonium-238 – only half of it will be gone after 88 years.

Space is almost empty, so the Voyagers are not at a significant level of risk of bombardment by large objects. However, Voyager 1’s interstellar space environment is not a complete void. It’s filled with clouds of dilute material remaining from stars that exploded as supernovae millions of years ago. This material doesn’t pose a danger to the spacecraft, but is a key part of the environment that the Voyager mission is helping scientists study and characterize.

Because the Voyagers’ power decreases by four watts per year, engineers are learning how to operate the spacecraft under ever-tighter power constraints. And to maximize the Voyagers’ life spans, they also have to consult documents written decades earlier describing commands and software, in addition to the expertise of former Voyager engineers.

“The technology is many generations old, and it takes someone with 1970s design experience to understand how the spacecraft operate and what updates can be made to permit them to continue operating today and into the future,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Team members estimate they will have to turn off the last science instrument by 2030. However, even after the spacecraft go silent, they’ll continue on their trajectories at their present speed of more than 30,000 mph (48,280 kilometers per hour), completing an orbit within the Milky Way every 225 million years.

The Voyager spacecraft were built by JPL, which continues to operate both. The Voyager missions are part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of SMD.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit:

Dwayne Brown / Laurie Cantillo Headquarters, Washington 202-358-1726 / 202-358-1077 [email protected] / [email protected] Elizabeth Landau / Jia-Rui Cook Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. 818-354-6425 / 818-354-0724 [email protected] / [email protected]

Things are finally looking up for the Voyager 1 interstellar spacecraft

Two of the four science instruments aboard the Voyager 1 spacecraft are now returning usable data after months of transmitting only gibberish, NASA scientists have announced.

I was once sitting with my father while Googling how far away various things in the solar system are from Earth. He was looking for exact numbers, and very obviously grew more invested with each new figure I shouted out. I was thrilled. The moon? On average, 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers) away. The James Webb Space Telescope ? Bump that up to about a million miles (1,609,344 km) away. The sun? 93 million miles (149,668,992 km) away. Neptune ? 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion km) away. "Well, wait until you hear about Voyager 1," I eventually said, assuming he was aware of what was coming. He was not.

"NASA's Voyager 1 interstellar spacecraft actually isn't even in the solar system anymore," I announced. "Nope, it's more than 15 billion miles (24 billion km) away from us — and it's getting even farther as we speak." I can't quite remember his response, but I do indeed recall an expression of sheer disbelief. There were immediate inquiries about how that's even physically possible. There were bewildered laughs, different ways of saying "wow," and mostly, there was a contagious sense of awe. And just like that, a new Voyager 1 fan was born.

It is easy to see why Voyager 1 is among the most beloved robotic space explorers we have — and it is thus easy to understand why so many people felt a pang to their hearts several months ago, when Voyager 1 stopped talking to us.

Related: After months of sending gibberish to NASA, Voyager 1 is finally making sense again

For reasons unknown at the time, this spacecraft began sending back gibberish in place of the neatly organized and data-rich 0's and 1's it had been providing since its launch in 1977 . It was this classic computer language which allowed Voyager 1 to converse with its creators while earning the title of "farthest human made object." It's how the spacecraft relayed vital insight that led to the discovery of new Jovian moons and, thanks to this sort of binary podcast, scientists incredibly identified a new ring of Saturn and created the solar system's first and only "family portrait." This code, in essence, is crucial to Voyager 1's very being.

Plus, to make matters worse, the issue behind the glitch turned out to be associated with the craft's Flight Data System, which is literally the system that transmits information about Voyager 1's health so scientists can correct any issues that arise. Issues like this one. Furthermore, because of the spacecraft's immense distance from its operators on Earth, it takes about 22.5 hours for a transmission to reach the spacecraft, and then 22.5 hours to receive a transmission back. Alas, things weren't looking good for a while — for about five months, to be precise.

But then, on April 20, Voyager 1 finally phoned home with legible 0's and legible 1's.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The team had gathered early on a weekend morning to see whether telemetry would return," Bob Rasmussen, a member of the Voyager flight team, told Space.com. "It was nice to have everyone assembled in one place like this to share in the moment of learning that our efforts had been successful. Our cheer was both for the intrepid spacecraft and for the comradery that enabled its recovery."

And then, on May 22 , Voyager scientists released the welcome announcement that the spacecraft has successfully resumed returning science data from two of its four instruments, the plasma wave subsystem and magnetometer instrument. They're now working on getting the other two, the cosmic ray subsystem and low energy charged particle instrument, back online as well. Though there technically are six other instruments onboard Voyager, those had been out of commission for some time.

The comeback

Rasmussen was actually a member of the Voyager team in the 1970s, having worked on the project as a computer engineer before leaving for other missions including Cassini , which launched the spacecraft that taught us almost everything we currently know about Saturn. In 2022, however, he returned to Voyager because of a separate dilemma with the mission — and has remained on the team ever since.

"There are many of the original people who were there when Voyager launched, or even before, who were part of both the flight team and the science team," Linda Spilker, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory , who also worked on the Voyager mission, told Space.com in the This Week from Space podcast on the TWiT network. "It's a real tribute to Voyager — the longevity not only of the spacecraft, but of the people on the team."

To get Voyager 1 back online, in rather cinematic fashion, the team devised a complex workaround that prompted the FDS to send a copy of its memory back to Earth. Within that memory readout, operators managed to discover the crux of the problem — a corrupted code spanning a single chip — which was then remedied through another (honestly, super interesting ) process to modify the code. On the day Voyager 1 finally spoke again, "you could have heard a pin drop in the room," Spilker said. "It was very silent. Everybody's looking at the screen, waiting and watching."

Of course, Spilker also brought in some peanuts for the team to munch on — but not just any peanuts. Lucky peanuts.

It's a longstanding tradition at JPL to have a peanut feast before major mission events like launches, milestones and, well, the possible resurrection of Voyager 1. It began in the 1960s, when the agency was trying to launch the Ranger 7 mission that was meant to take pictures of and collect data about the moon's surface. Rangers 1 through 6 had all failed, so Ranger 7 was a big deal. As such, the mission's trajectory engineer, Dick Wallace, brought lots of peanuts for the team to nibble on and relax. Sure enough, Ranger 7 was a success and, as Wallace once said, "the rest is history."

Voyager 1 needed some of those positive snacky vibes.

"It'd been five months since we'd had any information," Spilker explained. So, in this room of silence besides peanut-eating-noises, Voyager 1 operators sat at their respective system screens, waiting.

"All of a sudden it started to populate — the data," Spilker said. That's when the programmers who had been staring at those screens in anticipation leapt out of their seats and began to cheer: "They were the happiest people in the room, I think, and there was just a sense of joy that we had Voyager 1 back."

Eventually, Rasmussen says the team was able to conclude that the failure probably occurred due to a combination of aging and radiation damage by which energetic particles in space bombarded the craft. This is also why he believes it wouldn't be terribly surprising to see a similar failure occur in the future, seeing as Voyager 1 is still roaming beyond the distant boundaries of our stellar neighborhood just like its spacecraft twin, Voyager 2 .

To be sure, the spacecraft isn't fully fixed yet — but it's lovely to know things are finally looking up, especially with the recent news that some of its science instruments are back on track. And, at the very least, Rasmussen assures that nothing the team has learned so far has been alarming. "We're confident that we understand the problem well," he said, "and we remain optimistic about getting everything back to normal — but we also expect this won't be the last."

In fact, as Rasmussen explains, Voyager 1 operators first became optimistic about the situation just after the root cause of the glitch had been determined with certainty. He also emphasizes that the team's spirits were never down. "We knew from indirect evidence that we had a spacecraft that was mostly healthy," he said. "Saying goodbye was not on our minds."

"Rather," he continued, "we wanted to push toward a solution as quickly as possible so other matters on board that had been neglected for months could be addressed. We're now calmly moving toward that goal."

The future of Voyager's voyage

It can't be ignored that, over the last few months, there has been an air of anxiety and fear across the public sphere that Voyager 1 was slowly moving toward sending us its final 0 and final 1. Headlines all over the internet, one written by myself included , have carried clear, negative weight. I think it's because even if Voyager 2 could technically carry the interstellar torch post-Voyager 1, the prospect of losing Voyager 1 felt like the prospect of losing a piece of history.

"We've crossed this boundary called the heliopause," Spilker explained of the Voyagers. "Voyager 1 crossed this boundary in 2012; Voyager 2 crossed it in 2018 — and, since that time, were the first spacecraft ever to make direct measurements of the interstellar medium." That medium basically refers to material that fills the space between stars. In this case, that's the space between other stars and our sun, which, though we don't always think of it as one, is simply another star in the universe. A drop in the cosmic ocean.

"JPL started building the two Voyager spacecraft in 1972," Spilker explained. "For context, that was only three years after we had the first human walk on the moon — and the reason we started that early is that we had this rare alignment of the planets that happens once every 176 years ." It was this alignment that could promise the spacecraft checkpoints across the solar system, including at Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Those checkpoints were important for the Voyagers in particular. Alongside planetary visits come gravity assists, and gravity assists can help fling stuff within the solar system — and, now we know, beyond.

As the first humanmade object to leave the solar system, as a relic of America's early space program, and as a testament to how robust even decades-old technology can be, Voyager 1 has carved out the kind of legacy usually reserved for remarkable things lost to time.

"Our scientists are eager to see what they’ve been missing," Rasmussen remarked. "Everyone on the team is self-motivated by their commitment to this unique and important project. That's where the real pressure comes from."

Still, in terms of energy, the team's approach has been clinical and determined.

— NASA's Voyager 1 sends readable message to Earth after 4 nail-biting months of gibberish

— NASA engineers discover why Voyager 1 is sending a stream of gibberish from outside our solar system

— NASA's Voyager 1 probe hasn't 'spoken' in 3 months and needs a 'miracle' to save it

"No one was ever especially excited or depressed," he said. "We're confident that we can get back to business as usual soon, but we also know that we're dealing with an aging spacecraft that is bound to have trouble again in the future. That's just a fact of life on this mission, so not worth getting worked up about."

Nonetheless, I imagine it's always a delight for Voyager 1's engineers to remember this robotic explorer occupies curious minds around the globe. (Including my dad's mind now, thanks to me and Google.)

As Rasmussen puts it: "It's wonderful to know how much the world appreciates this mission."

Originally posted on Space.com .

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

2 new helium leaks discovered on Boeing's Starliner — forcing NASA astronauts to skip sleep to fix them

LIFTOFF! Boeing Starliner carries 2 astronauts to space in 'final test' for NASA (watch live)

An encounter with 'something outside of the solar system' may have triggered an ice age on Earth

Most Popular

- 2 100-foot 'walking tree' in New Zealand looks like an Ent from Lord of the Rings — and is the lone survivor of a lost forest

- 3 Space photo of the week: James Webb and Chandra telescopes spot a 'lighthouse' pointed at Earth

- 4 1st Neuralink user describes highs and lows of living with Elon Musk's brain chip

- 5 James Webb telescope finds carbon at the dawn of the universe, challenging our understanding of when life could have emerged

- 2 'Physics itself disappears': How theoretical physicist Thomas Hertog helped Stephen Hawking produce his final, most radical theory of everything

- 3 1,600-year-old Hun burial in Poland contains 2 boys, including one with a deformed skull

- 4 James Webb telescope reveals 'cataclysmic' asteroid collision in nearby star system

- 5 DARPA's military-grade 'quantum laser' will use entangled photons to outshine conventional laser beams

Voyager 1 is back to life in interstellar space, but for how long?

NASA engineers have succeeded in breathing new life into Voyager 1 after the spacecraft, launched in 1977, went silent seven months ago.

NASA engineers have succeeded in breathing new life into Voyager 1 , the spacecraft launched in 1977 and once again communicating after it went silent seven months ago. But now comes another challenge: Keeping Voyager 1 scientifically useful for as long as possible as it probes a realm where no spacecraft has gone before .

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2 , are treasured at NASA not only because they have sent home astonishing images of the outer planets, but also because in their dotage, they are still doing science that can’t be readily duplicated.

They are now in interstellar space, far beyond the orbits of Neptune and Pluto. Voyager 1 is more than 15 billion miles from Earth and Voyager 2 nearly 13 billion miles. Both have passed the heliopause , where the “solar wind” of particles streaming from the sun terminates.

“They’re going someplace where we have nothing, we have no information,” NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy said. “We don’t know anything about the interstellar medium. Is it a highly charged environment? Are there a lot of dust particles out there?”

Even as the Voyagers continue their journeys, engineers and scientists at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. are mourning the loss of Ed Stone, the scientist who guided the mission from 1972 until his retirement in 2022. Stone, a former director of JPL, died June 9 at the age of 88.

“It’s great. This is exploration. This is wonderful,” Stone told The Washington Post in 2013 when he and his colleagues determined that Voyager 1 had reached interstellar space.

Voyager 1 has four scientific instruments still operational in this extended phase of its mission, but it suddenly ceased sending intelligible data on Nov. 14. A “tiger team” of engineers at JPL spent the ensuing months identifying the problem — a malfunctioning computer chip — and restoring communication.

That laborious process is nearly complete. Data is coming from all four instruments, project scientist Linda Spilker said, though engineers are still checking to see whether data from two of the instruments is fully usable.

What no one can change, though, is the mortality of a spacecraft with a limited power supply. Voyager 1 is running on fumes, or, more precisely, on the dwindling power from the radioactive decay of plutonium.

The Voyagers have traveled so far from the sun they can’t rely on solar power and instead use a radioisotope thermoelectric generator. But an RTG doesn’t last forever. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 will eventually go silent as they continue to cruise the galaxy. NASA scientists and engineers are hoping Voyager 1 can keep sending data until at least Sept. 5, 2027, the 50th anniversary of its launch.

“At some point, we’ll have to start turning off the science instruments one by one,” Spilker said. “Once we’re out of power, then we can no longer keep the spacecraft pointed at the Earth. And so [the Voyagers] will then continue on as what I like to think of as our silent ambassadors.”

In a sense, this is all a bonus because the primary mission for the two Voyagers was the exploration of the outer planets. Both visited Jupiter and Saturn, and Voyager 2 went on to Uranus and Neptune in what was known as the “Grand Tour” of the outer solar system, enabled by a rare orbital arrangement of the planets. The Voyagers delivered spectacular close-up images of the outer planets, and the mission ranks among NASA’s greatest achievements.

The gravitational slingshot from the planetary encounters sent Voyager 1 out of the elliptical plane of the solar system and did the same to Voyager 2 in a different direction.

About four years ago, Voyager 1 encountered something unexpected — a phenomenon scientists have dubbed a pressure front. Jamie Rankin, deputy project scientist, said the instruments on the spacecraft picked up a sudden change in the magnetic field of the interstellar environment, as well as a sudden increase in the density of particles.

What exactly caused this change remains unknown. But NASA scientists are eager to get all the data flowing normally again to see whether the pressure front is still detectable.

“Is the pressure front still there; what is happening with it?” Melroy said.

Voyager 1 is heading toward the constellation Ophiuchus, according to NASA, and in about 38,000 years, it will come within 1.7 light-years of an unremarkable star near the Little Dipper. But although it will have long gone silent, it does carry the equivalent of a message in a bottle: the “Golden Record.”

The record was curated by a committee led by astronomer Carl Sagan and includes greetings in 55 languages, sounds of surf, wind and thunderstorms, a whale song and music ranging from Beethoven to Chuck Berry to a Navajo chant. The Golden Record is accompanied by instructions for playing it, should the spacecraft someday come into the hands of an intelligent species interested in finding out about life on Earth.

“The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space,” Sagan said.

But that advanced spacefaring civilization might not be an alien one, NASA scientists point out. It’s conceivable that the cosmic message in a bottle could be picked up someday by a human deep-space mission eager to examine a vintage spaceship.

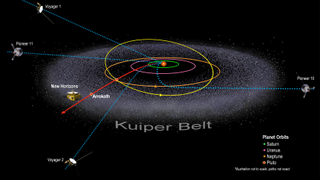

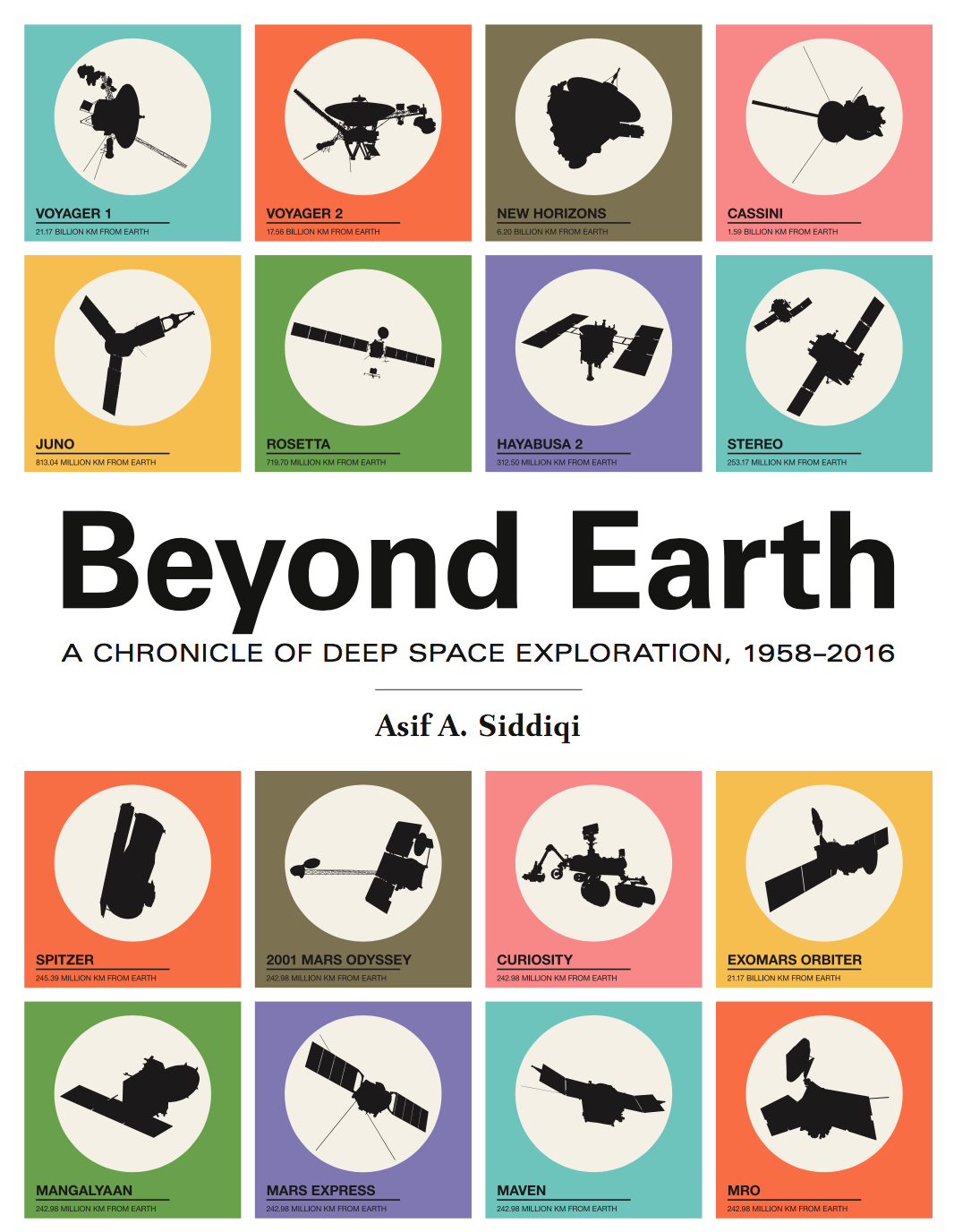

The most distant spacecraft in the solar system — Where are they now?

Humans have been flinging things into deep space for 50 years now, since the 1972 launch of Pioneer 10. We now have five spacecraft that have either reached the edges of our solar system or are fast approaching it: Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, Voyager 2 and New Horizons.

Most of these probes have defied their expected deaths and are still operating long beyond their original mission plans. These spacecraft were originally planned to explore our neighboring planets, but now they're blazing a trail out of the solar system , providing astronomers with unique vantage points in space — and they've been up to a lot in 2022.

Voyagers 1 and 2

The Voyager missions celebrated a very special anniversary this year: 45 years of operations . From close fly-bys of the outer planets to exploring humans' furthest reach in space, these two spacecraft have contributed immensely to astronomers' understanding of the solar system.

Related : Voyager: 15 incredible images of our solar system captured by the twin probes (gallery)

Their main project now is exploring where the sun 's influence ends, and other stars' influences begin. Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause, the boundary where the sun's flow of particles ceases to be the most important influence, in 2012 with Voyager 2 following close after, in 2018.

"Voyager 1 has now been in interstellar space for a decade…and it's still going, still going strong," Linda Spilker, Voyager project scientist and a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, told Space.com.

The mission team hit one major hiccup this year, when the spacecraft began sending home garbled information about its location. The engineers found the cause — the spacecraft was using a bad piece of computer hardware when it shouldn't have — and restored operations.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These kinds of incidents are to be expected with an aging spacecraft, though. The team is also actively managing the power supply onboard each spacecraft, which is dwindling each year as the probes' radioactive generators grow increasingly inefficient. This year, mission personnel turned off heaters keeping a number of scientific instruments on board warm in the harsh, cold environment of space — and, much to everyone's surprise, those instruments are still working perfectly well.

The cameras may have been turned off decades ago, but the spacecrafts' other instruments are collecting data on the plasma and magnetic fields from the sun at a great distance away from the star itself. Because particles of the solar wind — the constant stream of charged particles flowing off the sun — take time to travel such a long way, distant observations allow scientists to see how changes from the sun propagate throughout our cosmic neighborhood.

The edges of the solar system have been full of surprises, too. It would make sense that plasma from the sun becomes more sparse and spread out as you move away from the center of the solar system, but in fact, the Voyagers have encountered much denser plasma after crossing the heliopause. Astronomers are still puzzled about that one.

"It's just so amazing that even after all this time we continue to see the sun's influence in interstellar space," Spilker said. "I'm looking forward to Voyager continuing to operate, perhaps reaching the 50th anniversary."

Pioneers 10 and 11

The Pioneer spacecraft hold a special place in space history because of their role as, you guessed it, pioneers. Unfortunately, these milestone 50-year-old spacecraft are non-functional — Pioneer 10 lost communications back in 2003, and Pioneer 11 has been silent since its last contact in 1995.

But both these spacecraft are marks of humanity's presence in the solar system, and they are still continuing on their journeys, even if we're not sending them commands or firing their rockets anymore. Once a spacecraft is set on a trajectory out of the solar system, according to the laws of physics, it won't stop unless something changes its course.

New Horizons

New Horizons is by far the youngest sibling of these groundbreaking missions, having just launched in 2006 . After completing its famous flyby of dwarf planet Pluto in 2015 , this probe has been zooming out of the solar system at record speed, set to reach the heliopause around 2040.

Not only has it completed its primary mission, but it successfully completed a flyby of the smaller Kuiper Belt object, Arrokoth , in 2019 as its first mission extension. Earlier this year, the spacecraft was put into hibernation mode because an extended mission hadn't yet been approved. But now, the team is excitedly moving into New Horizons' 2nd Kuiper Belt Extended Mission, or KEM2 for short. KEM2 began on Oct. 1 , although the spacecraft will hibernate until March 1, 2023.

In the meantime, the mission team is preparing for exciting new observations. With cutting-edge instruments — far more advanced than what the Voyagers carried in the 1970s — the team is prepared to use New Horizons as a powerhouse observatory in the distant solar system, providing a viewpoint we can't achieve here on Earth .

Bonnie Burrati, planetary scientist at JPL and member of the New Horizons team, is particularly looking forward to new views of Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs), the chunks of ice and rock beyond Neptune . New Horizons' unique position in the outer solar system provides new angles of looking at these KBOs, she said. Different views can tell astronomers about how rough the objects' surfaces are, among other things, based on how light scatters and creates shadows on them.

Another planetary scientist on the team from Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, Leslie Young, wants to use the spacecraft for a new look at something closer to home: the ice giants, Uranus and Neptune. New Horizons’ unique viewpoint provides scientists with information about how light scatters through the planets’ atmospheres—information we can’t get from here on Earth, since we can’t see Uranus and Neptune from that angle. Planetary scientists are eager for more information about these planets, especially as NASA begins planning for a new mission to visit Uranus.

— The icy 'space snowman' Arrokoth in deep space just got names for its best features — Pale Blue Dot at 30: Voyager 1's iconic photo of Earth from space reveals our place in the universe — Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons mission in pictures

When the spacecraft wakes from hibernation, it will be past the so-called "Kuiper cliff," where scientists currently think there are far fewer large KBOs. "When we look at other star systems, we see debris disks extending to much larger distances from their host stars," Bryan Holler, an astronomer at Baltimore's Space Telescope Science Institute, told Space.com. "If ET were to look at our solar system, would they see the same thing?"

This next extended mission will even venture beyond New Horizons' original domain of planetary science. Now, the spacecraft will provide better-than-ever measurements of the background of light and cosmic rays in space, trace the distributions of dust throughout our solar system, and obtain crucial information on the sun's influence, complimentary to the Voyagers. Since the three functional far out spacecraft are heading in separate directions, they allow astronomers to map out irregularities in the solar system's structure.

Luckily for New Horizons, signs indicate that the spacecraft will have enough power to last through the 2040s and possibly beyond — each year, moving 300 million miles (480 million kilometers) farther into uncharted territory.

Follow the author at @ briles_34 on Twitter. Follow us on Twitter @ Spacedotcom and on Facebook .

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Briley Lewis (she/her) is a freelance science writer and Ph.D. Candidate/NSF Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles studying Astronomy & Astrophysics. Follow her on Twitter @briles_34 or visit her website www.briley-lewis.com .

Is there really a huge subsurface lake near Mars' south pole?

China lands Chang'e 6 sample-return probe on far side of the moon, a lunar success (video)

'Star Trek V: The Final Frontier' at 35: Did William Shatner direct the cheesiest chapter in the franchise?

- bolide I wonder if the JWST could see any of these satellites, if it aimed in their direction. Reply

bolide said: I wonder if the JWST could see any of these satellites, if it aimed in their direction.

- View All 2 Comments

Most Popular

- 2 Is there really a huge subsurface lake near Mars' south pole?

- 3 Solar flare blasts out strongest radiation storm since 2017

- 4 Take a video tour of Boeing’s Starliner with its 2 NASA astronauts

- 5 A 'new star' could appear in the sky any night now. Here's how to see the Blaze Star ignite

Ask Smithsonian 2017

A Smithsonian magazine special report

How Far Can Voyager I Go?

The spacecraft will run out of power around 2025, but where will it travel to first?

Ken Croswell

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Borders-631.jpg)

To casual stargazers, space seems to have no boundaries. Yet fans of NASA’s farthest-flung spacecraft can’t stop talking about how the probe is on the verge of piercing a border surrounding the planets and plunging into the realm beyond.

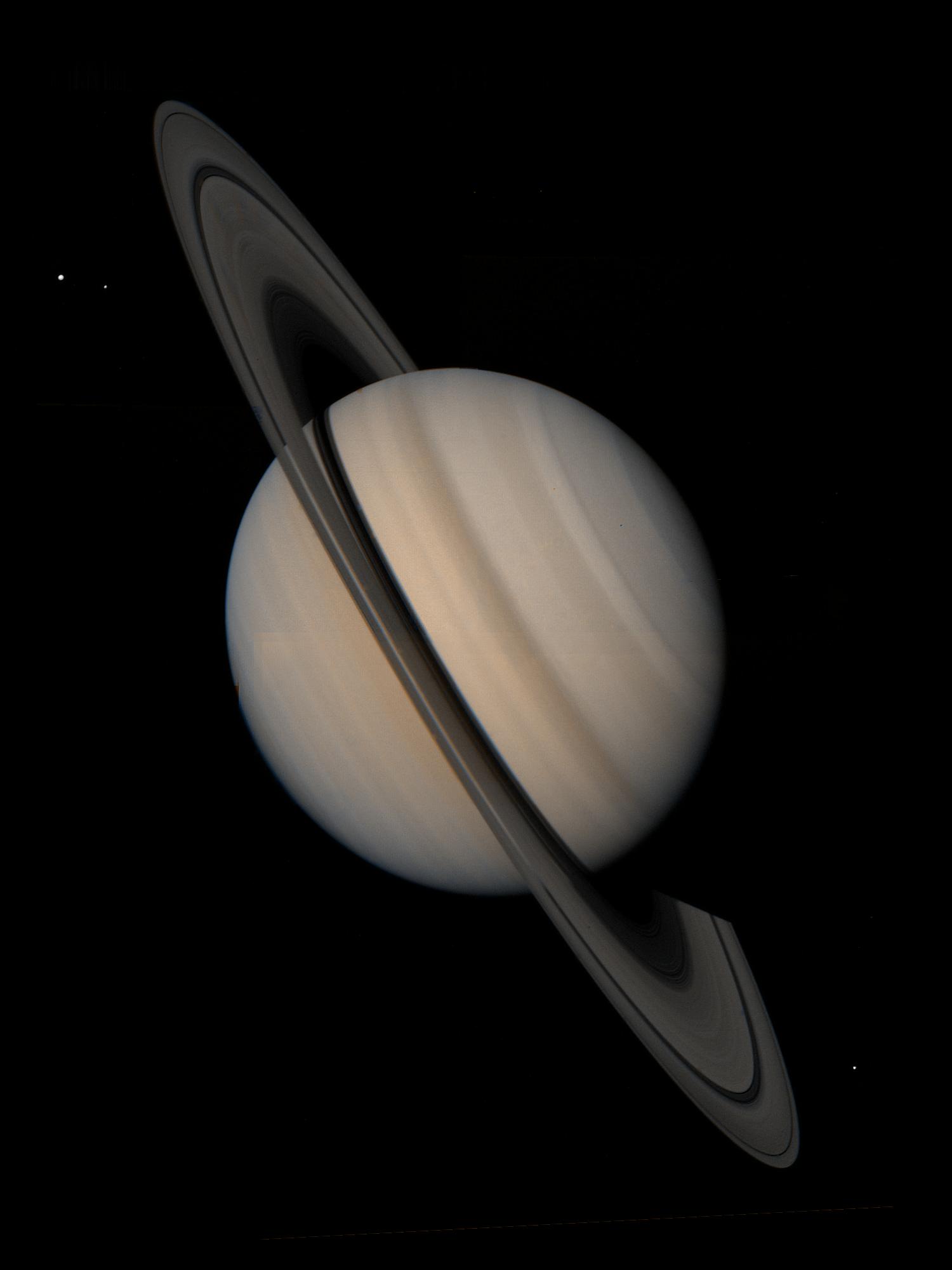

Since Voyager 1 blasted off in 1977, it has skirted past the kaleidoscopic clouds of Jupiter and the icy rings of Saturn. The spacecraft is now 124 times farther from the Sun than we are, and in the time it takes you to read this paragraph will venture outward 100 miles more. Its most recent observations raise questions about our solar system’s true reach.

Although we often consider Pluto the end of the solar system, Voyager 1 is more than three times farther than that and yet still within the Sun’s domain. Our mighty star currently shines on the probe with the brightness of more than a dozen full moons. The Sun makes its sphere of influence known with more than just visible light, spewing out a wind of particles that envelops the planets in a protective bubble called the heliosphere.

No one knows exactly how big this bubble is, which explains all the recent excitement. Back in 2004, Voyager 1 started seeing signs that the end was near, prompting some observers to talk about “the solar system’s edge.” The solar wind should slow abruptly as it presses against the space beyond, and Voyager saw just such a change. A twin probe, Voyager 2, saw the same thing in 2007. Last year, Voyager 1 witnessed another exit sign. The number of cosmic rays from interstellar space went up, perhaps because the Sun’s magnetic field can no longer deflect as many high-speed charged particles. But not until Voyager feels the magnetic field lines flip will astronomers know that the craft has escaped the heliosphere. “It could happen in the next several months, or it could be several more years,” says chief Voyager scientist Ed Stone of Caltech.

If Voyager 1 does manage to leave the heliosphere before it runs out of power around 2025, the spacecraft will probe the Local Cloud, a wisp of interstellar flotsam absorbing traces of light from nearby stars. The cloud is a cosmic wanderer, not a permanent feature, but it plays a role in the heliosphere’s size: It compresses the heliosphere, albeit just a little because the cloud is diffuse. In the past, dense clouds might have so squeezed the heliosphere that even Earth sat outside the shield, exposed to cosmic rays that may have helped or hindered the origin of life. Our home planet is surely part of the solar system, so any limit that excludes Earth can hardly mark the system’s outer bounds.

A better measure of that final frontier would be the extent of the Sun’s gravitational grip, which reaches much farther still. A trillion frigid objects orbit the Sun beyond Pluto and the heliosphere, in the Oort cloud of comets. Although no one knows for sure, the comets may reach halfway to Alpha Centauri, the closest star system at 4.3 light-years away. In that case, despite its swift speed, Voyager 1 is like a California-bound traveler who has walked just a few miles from the Atlantic seaboard. At the end of our lifetimes, the solar system’s ultimate boundary will remain far off.

“The sky’s the limit” may be just another way of saying there are no limits, but space does have borders. We just don’t know exactly where they are.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

The most distant human-made object

No spacecraft has gone farther than NASA's Voyager 1. Launched in 1977 to fly by Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012 and continues to collect data.

Mission Type

What is Voyager 1?

Voyager 1 has been exploring our solar system since 1977. The probe is now in interstellar space, the region outside the heliopause, or the bubble of energetic particles and magnetic fields from the Sun. Voyager 1 was launched after Voyager 2, but because of a faster route it exited the asteroid belt earlier than its twin, and it overtook Voyager 2 on Dec. 15, 1977.

- Voyager 1 discovered a thin ring around Jupiter and two new Jovian moons: Thebe and Metis.

- At Saturn, Voyager 1 found five new moons and a new ring called the G-ring.

- Voyager 1 was the first spacecraft to cross the heliosphere, the boundary where the influences from outside our solar system are stronger than those from our Sun.

- Voyager 1 is the first human-made object to venture into interstellar space.

In Depth: Voyager 1

Voyager 1 at jupiter.

Voyager 1 began its Jovian imaging mission in April 1978 at a range of 165 million miles (265 million km) from the planet. Images sent back by January the following year indicated that Jupiter’s atmosphere was more turbulent than during the Pioneer flybys in 1973–1974.

Beginning on Jan. 30, 1979, Voyager 1 took a picture every 96 seconds for a span of 100 hours to generate a color time-lapse movie to depict 10 rotations of Jupiter. On Feb. 10, the spacecraft crossed into the Jovian moon system and by early March, it had already discovered a thin (less than 19 miles, or 30 kilometers, thick) ring circling Jupiter.

Voyager 1’s closest encounter with Jupiter was at 12:05 UT on March 5, 1979 at a range of about 174,000 miles (280,000 kilometers). It encountered several of Jupiter’s moons, including Amalthea, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, returning spectacular photos of their terrain, opening up completely new worlds for planetary scientists.

The most interesting find was on Io, where images showed a bizarre yellow, orange, and brown world with at least eight active volcanoes spewing material into space, making it one of the most (if not the most) geologically active planetary body in the solar system. The presence of active volcanoes suggested that the sulfur and oxygen in Jovian space may be a result of the volcanic plumes from Io, which are rich in sulfur dioxide. The spacecraft also discovered two new moons, Thebe and Metis.

Voyager 1 at Saturn

Following the Jupiter encounter, Voyager 1 completed an initial course correction on April 9, 1979, in preparation for its meeting with Saturn. A second correction on Oct. 10, 1979, ensured that the spacecraft would not hit Saturn’s moon Titan.

Its flyby of the Saturn system in November 1979 was as spectacular as its previous encounter. Voyager 1 found five new moons, a ring system consisting of thousands of bands, wedge-shaped transient clouds of tiny particles in the B ring that scientists called “spokes,” a new ring (the “G-ring”), and “shepherding” satellites on either side of the F-ring—satellites that keep the rings well-defined.

During its flyby, the spacecraft photographed Saturn’s moons Titan, Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, and Rhea. Based on incoming data, all the moons appeared to be composed largely of water ice. Perhaps the most interesting target was Titan, which Voyager 1 passed at 05:41 UT on Nov. 12 at a range of 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers). Images showed a thick atmosphere that completely hid the surface. The spacecraft found that the moon’s atmosphere was composed of 90% nitrogen. Pressure and temperature at the surface was 1.6 atmospheres (1 atmosphere equals the average air pressure at sea level on Earth) and minus 290°F (minus 179°C), respectively.

Atmospheric data suggested that Titan might be the first body in the solar system (apart from Earth) where liquid could exist on the surface. In addition, the presence of nitrogen, methane, and more complex hydrocarbons indicated that prebiotic chemical reactions might be possible on Titan.

Voyager 1’s closest approach to Saturn was at 23:46 UT on Nov. 12, 1980, at a range of 78,000 miles (126,000 kilometers).

Voyager 1’s ‘Family Portrait’ Image

Following the encounter with Saturn, Voyager 1 headed on a trajectory escaping the solar system at a speed of about 3.5 AU per year, 35° out of the ecliptic plane to the north, in the general direction of the Sun’s motion relative to nearby stars. Because of the specific requirements for the Titan flyby, the spacecraft was not directed to Uranus and Neptune.

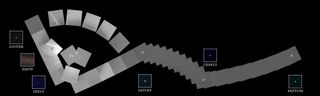

The final images taken by the Voyagers comprised a mosaic of 64 images taken by Voyager 1 on Feb. 14, 1990, at a distance of 40 AU, of the Sun and all the planets of the solar system (although Mercury and Mars did not appear, the former because it was too close to the Sun and the latter because Mars was on the same side of the Sun as Voyager 1 so only its dark side faced the cameras).

This was the so-called “pale blue dot” image made famous by Cornell University professor and Voyager science team member Carl Sagan (1934-1996). These were the last of a total of 67,000 images taken by the two spacecraft.

Voyager 1’s Interstellar Mission

With all the planetary encounters finally over in 1989, the missions of Voyager 1 and 2 were declared part of the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM), which officially began on Jan. 1, 1990.

The goal was to extend NASA’s exploration of the solar system beyond the neighborhood of the outer planets to the outer limits of the Sun’s sphere of influence, and “possibly beyond.” Specific goals include collecting data on the transition between the heliosphere, the region of space dominated by the Sun’s magnetic field and solar field, and the interstellar medium.

On Feb. 17, 1998, Voyager 1 became the most distant human-made object in existence when, at a distance of 69.4 AU from the Sun, it “overtook” Pioneer 10.

On Dec. 16, 2004, Voyager scientists announced that Voyager 1 had reported high values for the intensity for the magnetic field at a distance of 94 AU, indicating that it had reached the termination shock and had now entered the heliosheath.

The spacecraft finally exited the heliosphere and began measuring the interstellar environment on Aug. 25, 2012, the first spacecraft to do so.

On Sept. 5, 2017, NASA marked the 40th anniversary of its launch, as it continues to communicate with NASA’s Deep Space Network and send data back from four still-functioning instruments – the cosmic-ray telescope, the low-energy charged particles experiment, the magnetometer, and the plasma waves experiment.

The Golden Record

Each of the Voyagers contain a “message,” prepared by a team headed by Carl Sagan, in the form of a 12-inch (30-centimeter) diameter gold-plated copper disc for potential extraterrestrials who might find the spacecraft. Like the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11, the record has inscribed symbols to show the location of Earth relative to several pulsars.

The records also contain instructions to play them using a cartridge and a needle, much like a vinyl record player. The audio on the disc includes greetings in 55 languages, 35 sounds from life on Earth (such as whale songs, laughter, etc.), 90 minutes of generally Western music including everything from Mozart and Bach to Chuck Berry and Blind Willie Johnson. It also includes 115 images of life on Earth and recorded greetings from then-U.S. President Jimmy Carter (1924– ) and then-UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim (1918–2007).

By January 2024, Voyager 1 was about 136 AU (15 billion miles, or 20 billion kilometers) from Earth, the farthest object created by humans, and moving at a velocity of about 38,000 mph (17.0 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun.

National Space Science Data Center: Voyager 1

A library of technical details and historic perspective.

Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration

A comprehensive history of missions sent to explore beyond Earth.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

Two Voyager Spacecraft Still Going Strong After 20 Years

Twenty years after their launch and long after their planetary reconnaissance flybys were completed, both Voyager spacecraft are now gaining on another milestone -- crossing that invisible boundary that separates our solar system from interstellar space, the heliopause.

Since 1989, when Voyager 2 encountered Neptune, both spacecraft have been studying the environment of space in the outer solar system. Science instruments on both spacecraft are sensing signals that scientists believe are coming from the heliopause -- the outer most edge of the Sun's magnetic field that the spacecraft must pass through before they reach interstellar space.

"During their first two decades the Voyager spacecraft have had an unequaled journey of discovery. Today, even though Voyager 1 is now more than twice as far from the Sun as Neptune, their journey is only half over and more unique opportunities for discovery await the spacecraft as they head toward interstellar space," said Dr. Edward Stone, Voyager project scientist and director of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA. "The Voyagers owe their ability to operate at such great distances from the Sun to their nuclear electric power sources, which provide the electrical power they need to function."

The Sun emits a steady flow of electrically charged particles called the solar wind. As the solar wind expands supersonically into space, it creates a magnetized bubble around the Sun, called the heliosphere. Eventually, the solar wind encounters the electrically charged particles and magnetic field in the interstellar gas. The boundary created between the solar wind and interstellar gas is the heliopause. Before the spacecraft reach the heliopause, they will pass through the termination shock -- the zone in which the solar wind abruptly slows down from supersonic to subsonic speed.

Reaching the termination shock and heliopause will be major milestones for the spacecraft because no one has been there before and the Voyagers will gather the first direct evidence of their structure. Encountering the termination shock and heliopause has been a long-sought goal for many space physicists, and exactly where these two boundaries are located and what they are like still remains a mystery.

"Based on current data from the Voyager cosmic ray subsystem, we are predicting the termination shock to be in the range of 62 to 90 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. Most 'consensus' estimates are currently converging on about 85 AU. Voyager 1 is currently at about 67 AU and moving outwards at 3.5 AU per year, so I would expect crossing the termination shock sometime before the end of 2003," said Dr. Alan Cummings, a co- investigator on the cosmic ray subsystem at the California Institute of Technology.

"Based on a radio emission event detected by the Voyager 1 and 2 plasma wave instruments in 1992, we estimate that the heliopause is located at110 to 160 AU from the Sun," said Dr. Donald A. Gurnett, principal investigator on the plasma wave subsystem at the University of Iowa. (One AU is equal to 150 million kilometers, or 93 million miles, or the distance from the Earth to the Sun.)

"The low-energy charged particle instruments on the two spacecraft continue to detect ions and electrons accelerated at the Sun and at huge shock waves, tens of AU in radius, that are driven outward through the solar wind. During the past five years, we have observed marked variations in this ion population, but have yet to see clear evidence of the termination shock. We should always keep in mind that our theories may be incomplete and the shock may be a lot farther out than we think," said Dr. Stamatios M. Krimigis, principal investigator for the low energy charged particle subsystem at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Voyager 2 was launched first on Aug. 20, 1977 and Voyager 1 was launched a few weeks later on a faster trajectory on Sept. 5. Initially both spacecraft were only supposed to explore two planets -- Jupiter and Saturn. But the incredible success of those two first encounters and the good health of the spacecraft prompted NASA to extend Voyager 2's mission on to Uranus and Neptune. As the spacecraft flew across the solar system, remote-control reprogramming has given the Voyagers greater capabilities than they possessed when they left the Earth.

There are four other science instruments that are still functioning and collecting data as part of the Voyager Interstellar Mission. The plasma subsystem measures the protons in the solar wind. "Our instrument has recently observed a slow, year-long increase in the speed of the solar wind which peaked in late 1996, and we are now observing a slow decrease in solar wind velocity," said Dr. John Richardson, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, principal investigator on the plasma subsystem. "We think the velocity peak coincided with the recent solar minimum. As we approach the solar maximum in 2000 the solar wind pressure should decrease, which will result in the termination shock and heliopause moving inward towards the Voyager spacecraft."

The magnetometer on board the Voyagers measures the magnetic fields that are carried out into interplanetary space by the solar wind. The Voyagers are currently measuring the weakest interplanetary magnetic fields ever detected and those magnetic fields being measured are responsive to charged particles that cannot be detected directly by any other instruments on the spacecraft, according to Dr. Norman Ness, principal investigator on the magnetometer subsystem at the Bartol Research Institute, University of Delaware.

Other science instruments still collecting data include the planetary radio astronomy subsystem and the ultraviolet spectrometer subsystem.

Voyager 1 encountered Jupiter on March 5, 1979, and Saturn on November 12, 1980 and then, because its trajectory was designed to fly close to Saturn's large moon Titan, Voyager 1's path was bent northward by Saturn's gravity, sending the spacecraft out of the ecliptic plane, the plane in which all the planets except Pluto orbit the Sun. Voyager 2 arrived at Jupiter on July 9, 1979, and Saturn on August 25, 1981, and was then sent on to Uranus on January 25, 1986 and Neptune on August 25, 1989. Neptune's gravity bent Voyager 2's path southward, sending it out of the ecliptic plane as well and on toward interstellar space.

Both spacecraft have enough electrical power and attitude control propellant to continue operating until about 2020, when the available electrical power will no longer support science instrument operation. Spacecraft electrical power is supplied by Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) that provided approximately 470 watts power at launch. Due to the natural radioactive decay of the plutonium fuel source, the electrical energy provided by the RTGs is continually declining. At the beginning of 1997, the power generated by Voyager 1 had dropped to 334 watts and to 336 watts for Voyager 2. Both of these power levels represent better performance than had been predicted before launch.

The Voyagers are now so far from home that it takes nine hours for a radio signal traveling at the speed of light to reach the spacecraft. Science data are returned to Earth in real-time to the 34-meter Deep Space Network (DSN) antennas located in California, Australia and Spain. Voyager 1 will pass the Pioneer 10 spacecraft in January 1998 to become the most distant human- made object in our solar system.

Voyager 1 is currently 10.1 billion kilometers (6.3 billion miles) from Earth, having traveled 11.9 billion kilometers (7.4 billion miles) since its launch. The Voyager 1 spacecraft is departing the solar system at a speed of 17.4 kilometers per second (39,000 miles per hour).

Voyager 2 is currently 7.9 billion kilometers (4.9 billion miles) from Earth, having traveled 11.3 billion kilometers (6.9 billion miles) since its launch. The Voyager 2 spacecraft is departing the solar system at a speed of 15.9 kilometers per second (35,000 miles per hour).

JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology, manages the Voyager Interstellar Mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D. C.

Boeing's Starliner has 5 'small' helium leaks as astronauts' ISS mission is extended: NASA

The astronauts are now scheduled to return to Earth on June 18.

Boeing's Starliner spacecraft is experiencing five "small" helium leaks as its first astronaut-crewed flight test continues, the aerospace company and NASA said in an update on Monday.

While a major milestone was reached when Starliner successfully docked and delivered two NASA astronauts at the International Space Station (ISS) on June 6, the leaks mark the latest of several hurdles faced during this mission, including previous helium leaks and a thruster issue.

Helium is used to pressurize the spacecraft's reaction control system (RCS) maneuvering thrusters, allowing them to fire, according to Boeing .

MORE: NASA sets new launch date for Boeing Starliner's 1st astronaut-crewed flight after delays

The leaks are similar to those discovered during Starliner's May 25 launch attempt. That launch was scrubbed after a small helium leak was discovered in the service module, which contains support systems and instruments for operating the spacecraft.

Although it's unclear how much helium is leaking, Boeing said that engineers have evaluated the helium supply and the leak rates, and have concluded that Starliner has enough helium for its return mission.

The astronauts only need seven hours of "free-flight time" to perform the end-of-mission maneuvers and Starliner currently has enough helium for 70 hours of free-flight time, Boeing said.

"While Starliner is docked, all the manifolds are closed per normal mission operations preventing helium loss from the tanks," read the update from the aerospace company.

Engineers are also examining a valve that is not properly closed on the RCS. All other valves cycled normally during a check on Sunday, according to the update.

Astronauts Barry "Butch" Wilmore and Sunita "Suni" Williams are continuing to test Starliner as part of the data collection required for potential NASA certification to send regularly crewed missions to the ISS. NASA has primarily been using SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft to transport crew and cargo to the ISS.

Tests include making sure the spacecraft can power up again when it's put in minimal power mode during missions aboard the ISS, as well as ensuring Starliner can support a crew with its own air, evaluating seats onboard, and checking the service module's batteries, according to Boeing.

MORE: NASA's Voyager 1 sending readable data back to Earth for 1st time in 5 months

Wilmore and Williams were scheduled to return to Earth on Friday, June 14. However, the mission has been extended until June 18, pending weather and Starliner's readiness.

"@NASA and @BoeingSpace teams set a return date of no earlier than Tuesday, June 18, for the agency's Boeing Crew Flight Test," ISS officials wrote Sunday in a post on the social platform X . "The additional time in orbit will allow the crew to perform a spacewalk on Thursday, June 13, while engineers complete #Starliner systems checkouts."

The spacewalk will be performed by two different astronauts, but the extra days spent onboard will also allow preparations to be made for future spacewalks, NASA said on Monday.

Because Starliner's launch and ISS docking have been completed, the final phase of the current mission will be Starliner undocking from the ISS and then adjusting its orbit to move away from the space station before re-entering Earth's atmosphere and landing in the southwestern U.S.

ABC News' Gina Sunseri contributed to this report.

Related Topics

Trending reader picks.

Luke Bryan talks farewell to Katy Perry on 'Idol'

- Jun 11, 12:08 PM

Why Russia, China use faux females to get clicks

- Jun 12, 12:05 AM

'Wolfs' movie gets fast-paced new teaser

- Jun 11, 1:36 PM

DOT estimates $1.7 billion to rebuild Key Bridge

- Jun 12, 5:02 AM

US lifts weapons ban on controversial Ukraine unit

- Jun 11, 4:42 AM

ABC News Live

24/7 coverage of breaking news and live events

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

SpaceX’s Starship Rocket Successfully Completes 1st Return From Space

The company achieved a key set of ambitious goals on the fourth test flight of a vehicle that is central to Elon Musk’s vision of sending people to Mars.

SpaceX’s Starship Rocket Completes First Return From Space

Elon musk’s giant rocket, which launched from starbase in boca chica, texas, survived re-entry on its fourth test flight..

“We have liftoff.” “Vehicle is pitching down range.” “The Starship remains on a good entry trajectory.”

By Kenneth Chang

SpaceX’s launch of its mammoth Starship rocket on Thursday accomplished a set of ambitious goals that Elon Musk, the company’s chief executive, had set out before the test flight, the fourth.

Lifting off from SpaceX’s launchpad at 7:50 a.m. in South Texas, near Brownsville, Starship rumbled into the sky.

After it dropped away from the upper stage, the booster was able to gently set down in the Gulf of Mexico while the second-stage spacecraft traveled halfway around the world, survived the searing temperatures of re-entering the atmosphere and also made a controlled splashdown, in the Indian Ocean.

The flight was not flawless, and tough technical hurdles remain. The successes, surpassing what was accomplished during the previous test flight in March, offered optimism that Mr. Musk can pull off his vision of a rocket that is the biggest and most powerful ever and yet entirely reusable.

The outcome also helps validate the company’s break-it-then-fix-it approach to engineering, with steady progress since the first test launch in April last year when the rocket had to be deliberately destroyed when it flew off course.

“They are showing a capability to make progress more rapidly than we may have thought they’d been able to make,” said Daniel L. Dumbacher, executive director of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, a professional society for engineers. “They’ve got a team that knows what they’re doing, has the capability is willing to learn, and just as importantly, is not beholden to past assumptions.”

If Starship can fly again and again, more like a jetliner than a conventional rocket, it could transform a global space launch industry that SpaceX already dominates.

Today’s flight is also likely encouraging for officials at NASA. They are counting on SpaceX to provide a version of Starship to take astronauts to the surface of the moon during NASA’s Artemis III mission, currently scheduled for late 2026.

Bill Nelson, the administrator of NASA, offered his congratulations on X, the social media site that Mr. Musk owns.

“We are another step closer to returning humanity to the Moon through #Artemis — then looking onward to Mars,” he wrote.

After reaching a peak altitude of about 130 miles, the Starship upper-stage vehicle fell back to Earth, as planned, and re-entered the atmosphere. Cameras on the spacecraft captured an vibrant glow of gases heating up beneath it.

At an altitude of about 30 miles, pieces started peeling away from one of the steering flaps near the top of the spacecraft, with the flap continued to work. The camera’s view then became obstructed when debris cracked the lens.

“The question is how much of the ship is left,” said Kate Tice, one of the hosts of the SpaceX broadcast.

Real-time data continued to stream back, relayed via SpaceX’s Starlink internet satellites, to the company’s headquarters in Hawthorne, Calif., all the way until the altitude was reported at 0 — the surface of the Indian Ocean.

A final engine burn flipped Starship to a vertical position just before landing.

“From South Texas to the other side of the Earth, Starship is in the water,” said Dan Huot, one of the other SpaceX webcast hosts. “What a day.”

A crowd of onlooking SpaceX employees outside mission control in California cheered wildly, with arms thrust upward in celebration.

“Despite loss of many tiles and a damaged flap, Starship made it all the way to a soft landing in the ocean!” Mr. Musk wrote on X.

The damaged flap and the loss of heat-resistant tiles points to crucial upgrades still needed. Otherwise, Starship would, like the space shuttles, require extensive refurbishment after each flight.

“But that’s all fixable,” Mr. Dumbacher said. “It’s a step in the right direction, and there are more steps that have to be taken.”

Earlier in the flight, the rocket’s first stage, the giant Super Heavy booster was also able to perform maneuvers that in the future would take it back to the launch site. For this flight, it simulated such a landing by setting down in the Gulf of Mexico. All three previous attempts at that feat have ended in explosions.

With the Starship vehicle stacked on top of the Super Heavy booster, the rocket is the tallest ever built — 397 feet tall, or about 90 feet taller than the Statue of Liberty, including the pedestal.

The Super Heavy has 33 of SpaceX’s powerful Raptor engines sticking out of its bottom.

As those engines lift Starship off the launchpad, they generate up to 16 million pounds of thrust at full throttle. On this flight, one of the engines failed to ignite, but that did not prevent it from continuing its trip to space.

A couple of weeks ago, after a successful launch rehearsal, Mr. Musk wrote on X that for this flight, “Primary goal is getting through max re-entry heating.”

In other words, he did not want the vehicle to burn up. And on Thursday, it did not.

The Starship launches have attracted spectators to SpaceX’s launch site near the southern tip of Texas.

On Thursday, they sat in beach chairs or atop pickup trucks and camper listening to the SpaceX broadcast. as the countdown continued.

“It is insane what they are doing here,” said Chris Thomassen, who had traveled from the Netherlands to watch the launch, camping out three days on a beach close to the launchpad, then moving to a spot just at the edge of the safety exclusion zone.

Robert Opel, 56, set up a tent outside the launch site four days before Thursday’s launch. He was so determined to see the liftoff from up close he had arranged to travel across the Rio Grande to Mexico, which is just a few miles from the launchpad.

“It is like all of your birthdays wrapped up into one,” Mr. Opel said, adding that this was the fourth — of four — Starship test launches that he had witnessed.

Eric Lipton contributed reporting from Boca Chica, Texas.

An earlier version of this article misstated the distance of the SpaceX launch site from the Mexican border. The launchpad is 2.5 miles the border, not within a few hundred feet.

How we handle corrections

Kenneth Chang , a science reporter at The Times, covers NASA and the solar system, and research closer to Earth. More about Kenneth Chang

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

The company SpaceX achieved a key set of ambitious goals on the fourth test flight of a vehicle that is central to Elon Musk’s vision of sending people to Mars.

Euclid, a European Space Agency telescope launched into space last summer, finally showed off what it’s capable of with a batch of breathtaking images and early science results.

A dramatic blast from the sun set off the highest-level geomagnetic storm in Earth’s atmosphere, making the northern lights visible around the world .

With the help of Google Cloud, scientists who hunt killer asteroids churned through hundreds of thousands of images of the night sky to reveal 27,500 overlooked space rocks in the solar system .

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

Watch CBS News

Boeing's Starliner capsule finally launches, but runs into more trouble with helium leaks

By William Harwood

Updated on: June 5, 2024 / 9:16 PM EDT / CBS News

A United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket blasted off Wednesday and safely boosted Boeing 's long-delayed Starliner crew ferry ship into space for its first piloted test flight. But flight controllers had to step in late in the day to troubleshoot additional, unexpected helium leaks in the ship's propulsion system.

The Starliner was launched with a small-but-persistent helium leak in a specific "manifold" — that is lines routing pressurized gas to valves that operate one specific thruster. The launch was delayed several weeks for troubleshooting, but managers concluded the spacecraft could be safely flown as is.

Late in the day Wednesday, flight controllers detected signs of two more helium leaks in different parts of the ship's plumbing and carried out steps to isolate the affected lines. That stopped the leakage, but disabled six of 28 reaction control system jets in four propulsion modules mounted on the Starliner's service module.

Mission managers said before launch that backup plans had been developed in case the original leak dramatically worsened, and NASA commentators stressed that Starliner commander Barry "Butch" Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams were in no danger, and that plans were being developed to manage the leaks as the mission continues.

But the troubleshooting put a damper on the elation that followed a picture-perfect launch. The crew's workhorse Atlas 5 rocket roared to life at 10:52 p.m. EDT, followed an instant later by ignition of two strap-on solid fuel boosters, to kick off a planned eight-day test flight.

Generating a combined 1.6 million pounds of thrust, the 197-foot Atlas 5 majestically climbed skyward from pad 41 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, arcing away to the northeast on a trajectory matching the orbital path of the space station - a requirement for rendezvous missions.

"We all know that when the going gets tough, and it often does, the tough get going," Wilmore radioed controllers from the Starliner's cockpit before launch. "And you have. And Suni and I are honored to share this dream of spaceflight with each and every one of you. So with that, let's get going! Let's put some fire in this rocket and push it toward the heavens!"

He got his wish.

The Atlas 5 dropped the Starliner off with a velocity just shy of what's required to reach orbit, a precaution to make sure the crew ship would re-enter and land safely even if a major problem knocked out its own propulsion system. But there were no problems, and a thruster firing 31 minutes after liftoff completed the ascent phase of the mission, putting the ship in the planned orbit.

The astronauts then spent the afternoon testing the Starliner's manual controls and overall operation before taking a moment to congratulate Boeing, United Launch Alliance and NASA for a problem-free climb to space. Wilmore could barely contain his enthusiasm.

"It is just an amazing, amazing spacecraft," he said of the Starliner. "Boeing's done a magnificent job. And thus far, like I said, things have just gone swimmingly, it's gone fabulously, put it like that. And so kudos to everybody. ULA? Love ya. Boeing? Love ya...It's been wonderful."

But shortly before the crew called it a day and prepared for sleep, the helium issue cropped up. Flight controllers promised Wilmore a detailed update after crew wakeup Thursday. Presumably, the helium leakage can be managed, permitting rendezvous and docking with the International Space Station just after noon.

The long-awaited flight marked the first launch of an Atlas 5 with astronauts aboard and the first for the Atlas family of rockets since astronaut Gordon Cooper took off just a few miles away on the Mercury program's final flight 61 years ago.

It also marks the first piloted flight of the Starliner, Boeing's answer to SpaceX's Crew Dragon, an already operational, less expensive spacecraft that has carried 50 astronauts, cosmonauts and civilians into orbit in 13 flights, 12 of them to the space station, since an initial piloted test flight in May 2020.

Despite a larger NASA contract, Boeing's Starliner is four years behind SpaceX getting astronauts to space. But Wilmore and Williams say the spacecraft is now safer and more capable thanks to numerous upgrades and fixes.

"I'm not going to say it's been easy. It's a little bit of (an) emotional roller coaster," Williams said before the crew's first launch attempt. But, she added, "we knew we would get here eventually. It's a solid spacecraft. I don't think I would really want to be in any other place right now."

While Wilmore and Williams are closing in on the space station Thursday, SpaceX plans to launch its gargantuan Super Heavy-Starship rocket on its fourth test flight from the company's Boca Chica, Texas, "Starbase" facility.

The booster will attempt a controlled splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico shortly after liftoff while the Starship upper stage continues into space, looping halfway around the planet before re-entry and splashdown in the Indian Ocean.

In three previous flights, both stages were destroyed in flight, but performance dramatically improved with each launch as upgrades and fixes were implemented, and SpaceX expects more of the same with the fourth test flight.

The Super Heavy has nothing to do with Boeing's Starliner or the space station, but NASA will be paying close attention because the agency plans to use a variant of the Starship to carry astronauts down to the moon's surface in its Artemis program. Perfecting the Super Heavy booster and Starship upper stage are crucial to those plans.

Wilmore and Williams plan to dock at the space station and be welcomed aboard by cosmonauts Oleg Kononenko, Nikolai Chub and Alexander Grebenkin, along with NASA's Matthew Dominick, Michael Barratt, Jeanette Epps and Tracy Dyson.

Kononenko logged his 1,000th day in space across five flights Tuesday, underscoring his title as the world's most experienced spaceman, 220 days beyond the previous mark of 879 days set by cosmonaut Gennady Padalka in 2015.

The Starliner is tentatively scheduled to undock and return to Earth on June 14, but the flight could be extended depending on the weather at desert landing sites in the western United States.

NASA funded development of Crew Dragon and Boeing's Starliner to end the agency's sole post-shuttle reliance on Russian Soyuz for flights to the space station. Two spacecraft from different vendors were ordered to ensure the agency would be able to launch crews to the outpost even if one company's ferry ship was grounded for any reason.

Boeing initially planned to launch the Starliner on its first piloted flight in 2020, but the spacecraft encountered multiple problems during an initial unpiloted launch in December 2019. The company fixed those issues and opted to launch a second uncrewed flight at its own expense but then ran into problems with corroded propulsion system valves.