- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Traveler's diarrhea

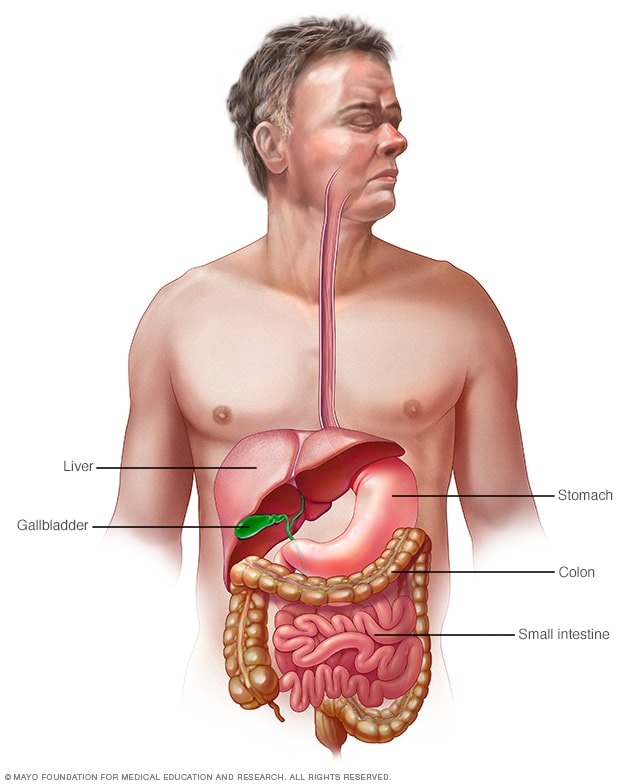

Gastrointestinal tract

Your digestive tract stretches from your mouth to your anus. It includes the organs necessary to digest food, absorb nutrients and process waste.

Traveler's diarrhea is a digestive tract disorder that commonly causes loose stools and stomach cramps. It's caused by eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea usually isn't serious in most people — it's just unpleasant.

When you visit a place where the climate or sanitary practices are different from yours at home, you have an increased risk of developing traveler's diarrhea.

To reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea, be careful about what you eat and drink while traveling. If you do develop traveler's diarrhea, chances are it will go away without treatment. However, it's a good idea to have doctor-approved medicines with you when you travel to high-risk areas. This way, you'll be prepared in case diarrhea gets severe or won't go away.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

Traveler's diarrhea may begin suddenly during your trip or shortly after you return home. Most people improve within 1 to 2 days without treatment and recover completely within a week. However, you can have multiple episodes of traveler's diarrhea during one trip.

The most common symptoms of traveler's diarrhea are:

- Suddenly passing three or more looser watery stools a day.

- An urgent need to pass stool.

- Stomach cramps.

Sometimes, people experience moderate to severe dehydration, ongoing vomiting, a high fever, bloody stools, or severe pain in the belly or rectum. If you or your child experiences any of these symptoms or if the diarrhea lasts longer than a few days, it's time to see a health care professional.

When to see a doctor

Traveler's diarrhea usually goes away on its own within several days. Symptoms may last longer and be more severe if it's caused by certain bacteria or parasites. In such cases, you may need prescription medicines to help you get better.

If you're an adult, see your doctor if:

- Your diarrhea lasts beyond two days.

- You become dehydrated.

- You have severe stomach or rectal pain.

- You have bloody or black stools.

- You have a fever above 102 F (39 C).

While traveling internationally, a local embassy or consulate may be able to help you find a well-regarded medical professional who speaks your language.

Be especially cautious with children because traveler's diarrhea can cause severe dehydration in a short time. Call a doctor if your child is sick and has any of the following symptoms:

- Ongoing vomiting.

- A fever of 102 F (39 C) or more.

- Bloody stools or severe diarrhea.

- Dry mouth or crying without tears.

- Signs of being unusually sleepy, drowsy or unresponsive.

- Decreased volume of urine, including fewer wet diapers in infants.

It's possible that traveler's diarrhea may stem from the stress of traveling or a change in diet. But usually infectious agents — such as bacteria, viruses or parasites — are to blame. You typically develop traveler's diarrhea after ingesting food or water contaminated with organisms from feces.

So why aren't natives of high-risk countries affected in the same way? Often their bodies have become used to the bacteria and have developed immunity to them.

Risk factors

Each year millions of international travelers experience traveler's diarrhea. High-risk destinations for traveler's diarrhea include areas of:

- Central America.

- South America.

- South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Traveling to Eastern Europe, South Africa, Central and East Asia, the Middle East, and a few Caribbean islands also poses some risk. However, your risk of traveler's diarrhea is generally low in Northern and Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Your chances of getting traveler's diarrhea are mostly determined by your destination. But certain groups of people have a greater risk of developing the condition. These include:

- Young adults. The condition is slightly more common in young adult tourists. Though the reasons why aren't clear, it's possible that young adults lack acquired immunity. They may also be more adventurous than older people in their travels and dietary choices, or they may be less careful about avoiding contaminated foods.

- People with weakened immune systems. A weakened immune system due to an underlying illness or immune-suppressing medicines such as corticosteroids increases risk of infections.

- People with diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe kidney, liver or heart disease. These conditions can leave you more prone to infection or increase your risk of a more-severe infection.

- People who take acid blockers or antacids. Acid in the stomach tends to destroy organisms, so a reduction in stomach acid may leave more opportunity for bacterial survival.

- People who travel during certain seasons. The risk of traveler's diarrhea varies by season in certain parts of the world. For example, risk is highest in South Asia during the hot months just before the monsoons.

Complications

Because you lose vital fluids, salts and minerals during a bout with traveler's diarrhea, you may become dehydrated, especially during the summer months. Dehydration is especially dangerous for children, older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

Dehydration caused by diarrhea can cause serious complications, including organ damage, shock or coma. Symptoms of dehydration include a very dry mouth, intense thirst, little or no urination, dizziness, or extreme weakness.

Watch what you eat

The general rule of thumb when traveling to another country is this: Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it. But it's still possible to get sick even if you follow these rules.

Other tips that may help decrease your risk of getting sick include:

- Don't consume food from street vendors.

- Don't consume unpasteurized milk and dairy products, including ice cream.

- Don't eat raw or undercooked meat, fish and shellfish.

- Don't eat moist food at room temperature, such as sauces and buffet offerings.

- Eat foods that are well cooked and served hot.

- Stick to fruits and vegetables that you can peel yourself, such as bananas, oranges and avocados. Stay away from salads and from fruits you can't peel, such as grapes and berries.

- Be aware that alcohol in a drink won't keep you safe from contaminated water or ice.

Don't drink the water

When visiting high-risk areas, keep the following tips in mind:

- Don't drink unsterilized water — from tap, well or stream. If you need to consume local water, boil it for three minutes. Let the water cool naturally and store it in a clean covered container.

- Don't use locally made ice cubes or drink mixed fruit juices made with tap water.

- Beware of sliced fruit that may have been washed in contaminated water.

- Use bottled or boiled water to mix baby formula.

- Order hot beverages, such as coffee or tea, and make sure they're steaming hot.

- Feel free to drink canned or bottled drinks in their original containers — including water, carbonated beverages, beer or wine — as long as you break the seals on the containers yourself. Wipe off any can or bottle before drinking or pouring.

- Use bottled water to brush your teeth.

- Don't swim in water that may be contaminated.

- Keep your mouth closed while showering.

If it's not possible to buy bottled water or boil your water, bring some means to purify water. Consider a water-filter pump with a microstrainer filter that can filter out small microorganisms.

You also can chemically disinfect water with iodine or chlorine. Iodine tends to be more effective, but is best reserved for short trips, as too much iodine can be harmful to your system. You can purchase water-disinfecting tablets containing chlorine, iodine tablets or crystals, or other disinfecting agents at camping stores and pharmacies. Be sure to follow the directions on the package.

Follow additional tips

Here are other ways to reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea:

- Make sure dishes and utensils are clean and dry before using them.

- Wash your hands often and always before eating. If washing isn't possible, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol to clean your hands before eating.

- Seek out food items that require little handling in preparation.

- Keep children from putting things — including their dirty hands — in their mouths. If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Tie a colored ribbon around the bathroom faucet to remind you not to drink — or brush your teeth with — tap water.

Other preventive measures

Public health experts generally don't recommend taking antibiotics to prevent traveler's diarrhea, because doing so can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotics provide no protection against viruses and parasites, but they can give travelers a false sense of security about the risks of consuming local foods and beverages. They also can cause unpleasant side effects, such as skin rashes, skin reactions to the sun and vaginal yeast infections.

As a preventive measure, some doctors suggest taking bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease the likelihood of diarrhea. However, don't take this medicine for longer than three weeks, and don't take it at all if you're pregnant or allergic to aspirin. Talk to your doctor before taking bismuth subsalicylate if you're taking certain medicines, such as anticoagulants.

Common harmless side effects of bismuth subsalicylate include a black-colored tongue and dark stools. In some cases, it can cause constipation, nausea and, rarely, ringing in your ears, called tinnitus.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Infectious enteritis and proctocolitis. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Microbiology, epidemiology, and prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Traveler diarrhea. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Diarrhea. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diarrhea. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Travelers' diarrhea. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Khanna S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 29, 2021.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

- GP practice services

- Health advice

- Health research

- Medical professionals

- Health topics

Advice and clinical information on a wide variety of healthcare topics.

All health topics

Latest features

Allergies, blood & immune system

Bones, joints and muscles

Brain and nerves

Chest and lungs

Children's health

Cosmetic surgery

Digestive health

Ear, nose and throat

General health & lifestyle

Heart health and blood vessels

Kidney & urinary tract

Men's health

Mental health

Oral and dental care

Senior health

Sexual health

Signs and symptoms

Skin, nail and hair health

- Travel and vaccinations

Treatment and medication

Women's health

Healthy living

Expert insight and opinion on nutrition, physical and mental health.

Exercise and physical activity

Healthy eating

Healthy relationships

Managing harmful habits

Mental wellbeing

Relaxation and sleep

Managing conditions

From ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, to steroids for eczema, find out what options are available, how they work and the possible side effects.

Featured conditions

ADHD in children

Crohn's disease

Endometriosis

Fibromyalgia

Gastroenteritis

Irritable bowel syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Scarlet fever

Tonsillitis

Vaginal thrush

Health conditions A-Z

Medicine information

Information and fact sheets for patients and professionals. Find out side effects, medicine names, dosages and uses.

All medicines A-Z

Allergy medicines

Analgesics and pain medication

Anti-inflammatory medicines

Breathing treatment and respiratory care

Cancer treatment and drugs

Contraceptive medicines

Diabetes medicines

ENT and mouth care

Eye care medicine

Gastrointestinal treatment

Genitourinary medicine

Heart disease treatment and prevention

Hormonal imbalance treatment

Hormone deficiency treatment

Immunosuppressive drugs

Infection treatment medicine

Kidney conditions treatments

Muscle, bone and joint pain treatment

Nausea medicine and vomiting treatment

Nervous system drugs

Reproductive health

Skin conditions treatments

Substance abuse treatment

Vaccines and immunisation

Vitamin and mineral supplements

Tests & investigations

Information and guidance about tests and an easy, fast and accurate symptom checker.

About tests & investigations

Symptom checker

Blood tests

BMI calculator

Pregnancy due date calculator

General signs and symptoms

Patient health questionnaire

Generalised anxiety disorder assessment

Medical professional hub

Information and tools written by clinicians for medical professionals, and training resources provided by FourteenFish.

Content for medical professionals

FourteenFish training

Professional articles

Evidence-based professional reference pages authored by our clinical team for the use of medical professionals.

View all professional articles A-Z

Actinic keratosis

Bronchiolitis

Molluscum contagiosum

Obesity in adults

Osmolality, osmolarity, and fluid homeostasis

Recurrent abdominal pain in children

Medical tools and resources

Clinical tools for medical professional use.

All medical tools and resources

Motion sickness

Travel sickness.

Peer reviewed by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP Last updated 16 Mar 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

In this series: Health advice for travel abroad Travelling to remote locations Ears and flying Jet lag Altitude sickness

Motion sickness (travel sickness) is common, especially in children. It is caused by repeated unusual movements during travelling, which send strong (sometimes confusing) signals to the balance and position sensors in the brain.

In this article :

What causes motion sickness, how long does motion sickness last, motion sickness symptoms, how to stop motion sickness, natural treatments for motion sickness, motion sickness medicines, what can a doctor prescribe for motion sickness, what should i do if i'm actually sick, what is mal de debarquement syndrome.

Continue reading below

Motion sickness is a normal response to repeated movements, such as going over bumps or around in a circle, send lots of messages to your brain. If you are inside a vehicle, particularly if you are focused on things that are inside the vehicle with you then the signals that your eyes send to the brain may tell it that your position is not changing, whilst your balance mechanisms say otherwise.

Your balance mechanisms in your inner ears sense different signals to those that your eyes are seeing which then sends your brain mixed, confusing messages. This confusion between messages then causes people to experience motion sickness.

Is motion sickness normal?

Motion sickness is a normal response that anyone can have when experiencing real or perceived motion. Although all people can develop motion sickness if exposed to sufficiently intense motion, some people are rarely affected while other people are more susceptible and have to deal with motion sickness very often.

Triggers for motion sickness

Motion sickness can also be triggered by anxiety or strong smells, such as food or petrol. Sometimes trying to read a book or a map can trigger motion sickness. Both in children and adults, playing computer games can sometimes cause motion sickness to occur.

Motion sickness is more common in children and also in women. Fortunately, many children grow out of having motion sickness. It is not known why some people develop motion sickness more than others. Symptoms can develop in cars, trains, planes and boats and on amusement park rides, etc.

Symptoms typically go when the journey is over; however, not always. In some people they last a few hours, or even days, after the journey ends.

There are various symptoms of motion sickness including::

Feeling sick (nausea and vomiting).

Sweating and cold sweats.

Increase in saliva.

Headaches .

Feeling cold and going pale.

Feeling weak.

Some general tips to avoid motion sickness include the following.

Prepare for your journey

Don't eat a heavy meal before travelling. Light, carbohydrate-based food like cereals an hour or two before you travel is best.

On long journeys, try breaking the journey to have some fresh air, drink some cold water and, if possible, take a short walk.

For more in-depth advice on travelling generally, see the separate leaflets called Health Advice for Travel Abroad , Travelling to Remote Locations , Ears and Flying (Aeroplane Ear) , Jet Lag and Altitude Sickness .

Plan where you sit

Keep motion to a minimum. For example, sit in the front seat of a car, over the wing of a plane, or on deck in the middle of a boat.

On a boat, stay on deck and avoid the cafeteria or sitting where your can smell the engines.

Breathe fresh air

Breathe fresh air if possible. For example, open a car window.

Avoid strong smells, particularly petrol and diesel fumes. This may mean closing the window and turning on the air conditioning, or avoiding the engine area in a boat.

Use your eyes and ears differently

Close your eyes (and keep them closed for the whole journey). This reduces 'positional' signals from your eyes to your brain and reduces the confusion.

Don't try to read.

Try listening to an audio book with your eyes closed. There is some evidence that distracting your brain with audio signals can reduce your sensitivity to the motion signals.

Try to sleep - this works mainly because your eyes are closed, but it is possible that your brain is able to ignore some motion signals when you are asleep.

Do not read or watch a film.

It is advisable not to watch moving objects such as waves or other cars. Don't look at things your brain expects to stay still, like a book inside the car. Instead, look ahead, a little above the horizon, at a fixed place.

If you are the driver you are less likely to feel motion sickness. This is probably because you are constantly focused on the road ahead and attuned to the movements that you expect the vehicle to make. If you are not, or can't be, the driver, sitting in the front and watching what the driver is watching can be helpful.

Treat your tummy gently

Avoid heavy meals and do not drink alcohol before and during travelling. It may also be worth avoiding spicy or fatty food.

Try to 'tame your tummy' with sips of a cold water or a sweet, fizzy drink. Cola or ginger ale are recommended.

Try alternative treatments

Sea-Bands® are acupressure bands that you wear on your wrists to put pressure on acupressure points that Chinese medicine suggests affects motion sickness. Some people find that they are effective.

Homeopathic medicines seem to help some people, and will not make you drowsy. The usual homeopathic remedy is called 'nux vom'. Follow the instructions on the packet.

All the techniques above which aim to prevent motion sickness will also help reduce it once it has begun. Other techniques, which are useful on their own to treat motion sickness but can also be used with medicines if required, are:

Breathe deeply and slowly and, while focusing on your breathing, listening to music. This has been proved to be effective in clinical trials.

Ginger - can improve motion sickness in some people (as a biscuit or sweet, or in a drink).

There are several motion sickness medicines available which can reduce, or prevent, symptoms of motion sickness. You can buy them from pharmacies or, in some cases, get them on prescription. They work by interfering with the nerve signals described above.

Medicines are best taken before the journey. They may still help even if you take them after symptoms have begun, although once you feel sick you won't absorb medicines from the stomach very well. So, at this point, tablets that you put against your gums, or skin patches, are more likely to be effective.

Hyoscine is usually the most effective medicine for motion sickness . It is also known as scopolamine. It works by preventing the confusing nerve messages going to your brain.

There are several brands of medicines which contain hyoscine - they also come in a soluble form for children. You should take a dose 30-60 minutes before a journey; the effect can last up to 72 hours. Hyoscine comes as a patch for people aged 10 years or over. (This is only available on prescription - see below.) Side-effects of hyoscine include dry mouth , drowsiness and blurred vision.

Side-effects of motion sickness medicines

Some medicines used for motion sickness may cause drowsiness. Some people are extremely sensitive to this and may find that they are so drowsy that they can't function properly at all. For others the effects may be milder but can still impair your reactions and alertness. It is therefore advisable not to drive and not to operate heavy machinery if you have taken them. In addition, some medicines may interfere with alcohol or other medication; your doctor or the pharmacist can advise you about this.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines can also be useful , although they are not quite as effective as hyoscine. However, they usually cause fewer side-effects. Several types of antihistamine are sold for motion sickness. All can cause drowsiness, although some are more prone to cause it than others; for example, promethazine , which may be of use for young children on long journeys, particularly tends to cause drowsiness. Older children or adults may prefer one that is less likely to cause drowsiness - for example, cinnarizine or cyclizine.

Remember, if you give children medicines which cause drowsiness they can sometimes be irritable when the medicines wear off.

See the separate article called How to manage motion sickness .

There are a number of anti-sickness medicines which can only be prescribed by your doctor. Not all of them always work well for motion sickness, and finding something that works may be a case of trial and error. All of them work best taken up to an hour before your journey, and work less well if used when you already feel sick. See also the separate leaflet called Nausea (Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment) for more detailed information about these medicines .

Hyoscine patch

Hyoscine, or scopolamine, patches are suitable for adults and for children over 10 years old. The medicine is absorbed through your skin, although this method of medicine delivery is slow so the patch works best if applied well before your journey.

You should stick the patch on to the skin behind the ear 5-6 hours before travelling (often this will mean late on the previous night) and remove it at the end of the journey.

Prochlorperazine

Prochlorperazine is a prescription-only medicine which works by changing the actions of the chemicals that control the tendency to be sick (vomit), in your brain. One form of prochlorperazine is Buccastem®, which is absorbed through your gums and does not need to be swallowed. Buccastem® tastes rather bitter but it can be effective for sickness when you are already feeling sick, as it doesn't have to be absorbed by the stomach.

Metoclopramide

Metoclopramide is a tablet used to speed up the emptying of your tummy. Slow emptying of the tummy is something that happens when you develop nausea and vomiting, so metoclopramide can help prevent this. It prevents nausea and vomiting quite effectively in some people. It can occasionally have unpleasant side-effects, particularly in children (in whom it is not recommended). Metoclopramide is often helpful for those who tend to have gastric reflux, those who have slow tummy emptying because of previous surgery, and those who have type 1 diabetes. Your GP will advise whether metoclopramide is suitable for you.

Domperidone

Domperidone , like metoclopramide, is sometimes used for sickness caused by slow tummy emptying. It is not usually recommended for motion sickness but is occasionally used if other treatments don't help. Domperidone is not a legal medicine in some countries, including the USA.

Ondansetron

Ondansetron is a powerful antisickness medicine which is most commonly used for sickness caused by chemotherapy, and occasionally used for morning sickness in pregnancy. It is not usually effective for motion sickness. This, and its relatively high cost means that it is not prescribed for motion sickness alone. However, for those undergoing chemotherapy, and for those who have morning sickness aggravated by travel, ondansetron may be helpful.

If you're actually sick you may find that this relieves your symptoms a little, although not always for very long. If you've been sick:

Try a cool flannel on your forehead, try to get fresh air on your face and do your best to find a way to rinse your mouth to get rid of the taste.

Don't drink anything for ten to twenty minutes (or it may come straight back), although (very) tiny sips of very cold water, coke or ginger ale may help.

After this, go back to taking all the prevention measures above.

Once you reach your destination you may continue to feel unwell. Sleep if you can, sip cold iced water, and - when you feel ready - try some small carbohydrate snacks. Avoid watching TV (more moving objects to watch!) until you feel a little better.

The sensation called 'mal de debarquement' (French for sickness on disembarking) refers to the sensation you sometimes get after travel on a boat, train or plane, when you feel for a while as though the ground is rocking beneath your feet. It is probably caused by the overstimulation of the balance organs during your journey. It usually lasts only an hour or two, but in some people it can last for several days, particularly after a long sea journey. It does not usually require any treatment.

Persistent mal de debarquement syndrome is an uncommon condition in which these symptoms may persist for months or years.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- Spinks A, Wasiak J ; Scopolamine (hyoscine) for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jun 15;(6):CD002851.

- Lackner JR ; Motion sickness: more than nausea and vomiting. Exp Brain Res. 2014 Aug;232(8):2493-510. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4008-8. Epub 2014 Jun 25.

- Leung AK, Hon KL ; Motion sickness: an overview. Drugs Context. 2019 Dec 13;8:2019-9-4. doi: 10.7573/dic.2019-9-4. eCollection 2019.

- Zhang LL, Wang JQ, Qi RR, et al ; Motion Sickness: Current Knowledge and Recent Advance. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016 Jan;22(1):15-24. doi: 10.1111/cns.12468. Epub 2015 Oct 9.

- Van Ombergen A, Van Rompaey V, Maes LK, et al ; Mal de debarquement syndrome: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2016 May;263(5):843-854. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7962-6. Epub 2015 Nov 11.

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 14 Mar 2028

16 mar 2023 | latest version.

Last updated by

Peer reviewed by

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Travel-Related Diagnoses Among U.S. Nonmigrant Travelers or Migrants Presenting to U.S. GeoSentinel Sites — GeoSentinel Network, 2012–2021

Surveillance Summaries / June 30, 2023 / 72(7);1–22

Please note: This report has been corrected. An erratum has been published.

Ashley B. Brown, MPH 1 ; Charles Miller, MSOR 1 ; Davidson H. Hamer, MD 2 ,3 ; Phyllis Kozarsky, MD 4 ; Michael Libman, MD 5 ; Ralph Huits, MD, PhD 6 ; Aisha Rizwan, MPH 7 ; Hannah Emetulu, MPH 7 ; Jesse Waggoner, MD 8 ; Lin H. Chen, MD 9 ,10 ; Daniel T. Leung, MD 11 ; Daniel Bourque, MD 3 ; Bradley A. Connor, MD 12 ; Carmelo Licitra, MD 13 ; Kristina M. Angelo, DO 1 ( View author affiliations )

Views: Views equals page views plus PDF downloads

Introduction, selected worldwide health event notifications, selected health event notifications in geosentinel, limitations, future directions, acknowledgments.

- Full Issue PDF

Problem/Condition: During 2012–2021, the volume of international travel reached record highs and lows. This period also was marked by the emergence or large outbreaks of multiple infectious diseases (e.g., Zika virus, yellow fever, and COVID-19). Over time, the growing ease and increased frequency of travel has resulted in the unprecedented global spread of infectious diseases. Detecting infectious diseases and other diagnoses among travelers can serve as sentinel surveillance for new or emerging pathogens and provide information to improve case identification, clinical management, and public health prevention and response.

Reporting Period: 2012–2021.

Description of System: Established in 1995, the GeoSentinel Network (GeoSentinel), a collaboration between CDC and the International Society of Travel Medicine, is a global, clinical-care–based surveillance and research network of travel and tropical medicine sites that monitors infectious diseases and other adverse health events that affect international travelers. GeoSentinel comprises 71 sites in 29 countries where clinicians diagnose illnesses and collect demographic, clinical, and travel-related information about diseases and illnesses acquired during travel using a standardized report form. Data are collected electronically via a secure CDC database, and daily reports are generated for assistance in detecting sentinel events (i.e., unusual patterns or clusters of disease). GeoSentinel sites collaborate to report disease or population-specific findings through retrospective database analyses and the collection of supplemental data to fill specific knowledge gaps. GeoSentinel also serves as a communications network by using internal notifications, ProMed alerts, and peer-reviewed publications to alert clinicians and public health professionals about global outbreaks and events that might affect travelers. This report summarizes data from 20 U.S. GeoSentinel sites and reports on the detection of three worldwide events that demonstrate GeoSentinel’s notification capability.

Results: During 2012–2021, data were collected by all GeoSentinel sites on approximately 200,000 patients who had approximately 244,000 confirmed or probable travel-related diagnoses. Twenty GeoSentinel sites from the United States contributed records during the 10-year surveillance period, submitting data on 18,336 patients, of which 17,389 lived in the United States and were evaluated by a clinician at a U.S. site after travel. Of those patients, 7,530 (43.3%) were recent migrants to the United States, and 9,859 (56.7%) were returning nonmigrant travelers.

Among the recent migrants to the United States, the median age was 28.5 years (range = <19 years to 93 years); 47.3% were female, and 6.0% were U.S. citizens. A majority (89.8%) were seen as outpatients, and among 4,672 migrants with information available, 4,148 (88.8%) did not receive pretravel health information. Of 13,986 diagnoses among migrants, the most frequent were vitamin D deficiency (20.2%), Blastocystis (10.9%), and latent tuberculosis (10.3%). Malaria was diagnosed in 54 (<1%) migrants. Of the 26 migrants diagnosed with malaria for whom pretravel information was known, 88.5% did not receive pretravel health information. Before November 16, 2018, patients’ reasons for travel, exposure country, and exposure region were not linked to an individual diagnosis. Thus, results of these data from January 1, 2012, to November 15, 2018 (early period), and from November 16, 2018, to December 31, 2021 (later period), are reported separately. During the early and later periods, the most frequent regions of exposure were Sub-Saharan Africa (22.7% and 26.2%, respectively), the Caribbean (21.3% and 8.4%, respectively), Central America (13.4% and 27.6%, respectively), and South East Asia (13.1% and 16.9%, respectively). Migrants with diagnosed malaria were most frequently exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa (89.3% and 100%, respectively).

Among nonmigrant travelers returning to the United States, the median age was 37 years (range = <19 years to 96 years); 55.7% were female, 75.3% were born in the United States, and 89.4% were U.S. citizens. A majority (90.6%) were seen as outpatients, and of 8,967 nonmigrant travelers with available information, 5,878 (65.6%) did not receive pretravel health information. Of 11,987 diagnoses, the most frequent were related to the gastrointestinal system (5,173; 43.2%). The most frequent diagnoses among nonmigrant travelers were acute diarrhea (16.9%), viral syndrome (4.9%), and irritable bowel syndrome (4.1%).

Malaria was diagnosed in 421 (3.5%) nonmigrant travelers. During the early (January 1, 2012, to November 15, 2018) and later (November 16, 2018, to December 31, 2021) periods, the most frequent reasons for travel among nonmigrant travelers were tourism (44.8% and 53.6%, respectively), travelers visiting friends and relatives (VFRs) (22.0% and 21.4%, respectively), business (13.4% and 12.3%, respectively), and missionary or humanitarian aid (13.1% and 6.2%, respectively). The most frequent regions of exposure for any diagnosis among nonmigrant travelers during the early and later period were Central America (19.2% and 17.3%, respectively), Sub-Saharan Africa (17.7% and 25.5%, respectively), the Caribbean (13.0% and 10.9%, respectively), and South East Asia (10.4% and 11.2%, respectively).

Nonmigrant travelers who had malaria diagnosed were most frequently exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa (88.6% and 95.9% during the early and later period, respectively) and VFRs (70.3% and 57.9%, respectively). Among VFRs with malaria, a majority did not receive pretravel health information (70.2% and 83.3%, respectively) or take malaria chemoprophylaxis (88.3% and 100%, respectively).

Interpretation: Among ill U.S. travelers evaluated at U.S. GeoSentinel sites after travel, the majority were nonmigrant travelers who most frequently received a gastrointestinal disease diagnosis, implying that persons from the United States traveling internationally might be exposed to contaminated food and water. Migrants most frequently received diagnoses of conditions such as vitamin D deficiency and latent tuberculosis, which might result from adverse circumstances before and during migration (e.g., malnutrition and food insecurity, limited access to adequate sanitation and hygiene, and crowded housing,). Malaria was diagnosed in both migrants and nonmigrant travelers, and only a limited number reported taking malaria chemoprophylaxis, which might be attributed to both barriers to acquiring pretravel health care (especially for VFRs) and lack of prevention practices (e.g., insect repellant use) during travel. The number of ill travelers evaluated by U.S. GeoSentinel sites after travel decreased in 2020 and 2021 compared with previous years because of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated travel restrictions. GeoSentinel detected limited cases of COVID-19 and did not detect any sentinel cases early in the pandemic because of the lack of global diagnostic testing capacity.

Public Health Action: The findings in this report describe the scope of health-related conditions that migrants and returning nonmigrant travelers to the United States acquired, illustrating risk for acquiring illnesses during travel. In addition, certain travelers do not seek pretravel health care, even when traveling to areas in which high-risk, preventable diseases are endemic. Health care professionals can aid international travelers by providing evaluations and destination-specific advice.

Health care professionals should both foster trust and enhance pretravel prevention messaging for VFRs, a group known to have a higher incidence of serious diseases after travel (e.g., malaria and enteric fever). Health care professionals should continue to advocate for medical care in underserved populations (e.g., VFRs and migrants) to prevent disease progression, reactivation, and potential spread to and within vulnerable populations. Because both travel and infectious diseases evolve, public health professionals should explore ways to enhance the detection of emerging diseases that might not be captured by current surveillance systems that are not site based.

Modern modes of transportation and growing economies have made traveling more efficient and accessible. This progress has resulted in a surge of international travel, including travel to remote destinations and lower-income countries ( 1 ). In 2019, a record 2.4 billion international tourist arrivals globally ( 2 ) were observed by the World Tourism Organization.

Four studies estimated that 43%–79% of travelers to low- and middle-income countries became ill with a travel-related health problem, some of whom needed medical care during or after travel ( 3 ). Certain groups (e.g., travelers visiting friends and relatives [VFRs] and migrants) are particularly at risk for acquiring travel-related diseases because of a lack of risk awareness, access to specialized health care and pretravel consultation, and trust in the health care system ( 4 , 5 ). In addition, travelers might introduce pathogens into new environments and populations, leading to the spread of novel and emerging infectious diseases ( 6 ). The 2019 measles outbreaks across Europe illustrated how travel and poor vaccination coverage among local populations can fuel an epidemic ( 7 ). These outbreaks resulted in the importation of measles to communities with low vaccination coverage in the United States, a country that had eliminated measles in 2000. The rapid spread of disease across international borders also was observed during the Ebola virus disease epidemic in West Africa during 2014–2016 ( 8 ) as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic ( 9 ). These events illustrate the dangers of introducing pathogens into geographic clusters of susceptible populations as well as the importance of vaccination and other preventative strategies to reduce the risk for importation and spread.

Studying illness among travelers improves case identification, clinical management, and public health prevention strategies and also helps to characterize the epidemiology of diseases and control their spread ( 10 ). Because international travel continues to increase, conducting surveillance and research regarding travel-related diseases will be instrumental in reducing global transmission. To identify travel-related diseases and facilitate rapid communication between clinicians and public health professionals globally, a surveillance system (e.g., GeoSentinel) is needed. Such connectivity can reduce the size of outbreaks while promoting the timely sharing of clinical insight regarding the diagnosis and treatment of patients.

The GeoSentinel Network (GeoSentinel) is a global, clinical-care–based surveillance and research network of travel and tropical medicine sites that monitors infectious diseases and other adverse health events that affect international travelers ( https://geosentinel.org/ ). Since its inception in 1995, GeoSentinel has remained at the forefront of travel-related sentinel surveillance and continues to refine its collection of epidemiologic data from ill travelers during and after travel.

This report describes GeoSentinel, key changes in its data collection, its successful detection of sentinel events, and future directions. This report also summarizes the data collected from migrants and returning U.S. nonmigrant travelers presenting for evaluation at a U.S. GeoSentinel site during 2012–2021. The findings in this report underscore the importance of global travel-related disease surveillance so that clinicians and public health professionals are aware of the most common travel-related illnesses and can develop improved treatment and prevention strategies.

The GeoSentinel Network

GeoSentinel is a collaboration between CDC and the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) and was established in the United States in 1995 with nine U.S. sites ( 11 ). During 1996–1997, the GeoSentinel network expanded globally. GeoSentinel’s primary purpose is to coordinate multiple clinical-care–based sites that operate a global, provider-based emerging infections sentinel network, conduct surveillance for travel-related infections, and communicate and help guide public health responses ( 12 ). Sites collaborate to report disease or population-specific findings through retrospective database analyses and the collection of supplemental data to fill specific knowledge gaps.

Sites and Affiliate Members

As of December 2021, GeoSentinel comprised 71 sites in 29 countries located on six continents ( Figure 1 ). GeoSentinel sites are health care facilities led by site directors and codirectors who are medical professionals with expertise in travel and tropical medicine. GeoSentinel also includes 164 affiliate members (formerly referred to as network members) who report sentinel or unusual travel medicine cases but do not enter data into the GeoSentinel database.

Eligible Patients

Patient data can be entered into the GeoSentinel database if the patient has crossed an international border and was seen at a GeoSentinel site with a possible travel-related illness or, in the case of certain migrants, for screening purposes upon entry into their arrival country. Data from patients who develop a complication from pretravel treatments (i.e., adverse effect from vaccinations or antimalarial medication) also might be entered, even if the patients have not yet departed on their trip.

Data Collection

GeoSentinel sites use a standardized data collection form (Supplementary Appendix, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/127681 ) to collect demographic, clinical, and travel-related information about patients and the illnesses acquired during travel. These data are collected electronically via a secure web-based data entry application based at CDC. Daily reports are generated for assistance in detecting events (i.e., unusual patterns or clusters of disease). The system emails these reports to both CDC and ISTM partners for review. If an unusual disease pattern or cluster of disease is detected, the GeoSentinel program manager sends an email to the site requesting additional information. Electronic validation is integrated into the database to reduce data entry errors and maintain data integrity. Whereas certain sites enter all travel-related cases into the GeoSentinel database, other sites only enter a convenience sample. Entry of cases into the GeoSentinel database and determination of travel association are at the discretion of the treating clinician. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.* Ethics clearance has been obtained by sites as required by their respective institutions.

Selected Variables and Definitions

The GeoSentinel database contains information obtained from patients evaluated at GeoSentinel sites during and after international travel. The following definitions were used during the study period.

Citizen. A person who is a legally recognized national of a country.

Clinical setting. The timing of the visit related to travel.

- During travel. The trip related to the current illness is in progress. This category includes expatriates seen in their country of residence for illnesses likely acquired in that country or where the country of exposure cannot be ascertained.

- After travel. The trip related to the current illness has been completed. This category also includes expatriates who acquire an illness during travel outside their current country of residence and where the relevant exposure is related to travel.

Diagnosis and diagnosis type. Site directors choose from approximately 475 diagnoses classified as either etiologic or syndromic. A write-in option is available on the data collection form if the diagnosis is not on the list.

- Etiologic. This diagnosis type reflects a specific disease. The “diagnosis status” of etiologic diagnoses might be “confirmed” or “probable” (see Diagnosis status).

- Syndromic. This diagnosis type reflects symptom- or syndrome-based etiologies when a more specific etiology is not known or could not be determined as a result of use of empiric therapy, self-limited disease, or inability to justify additional diagnostic tests beyond standard clinical practice. The “diagnosis status” of all syndromic diagnoses is “confirmed” (see Diagnosis status).

Diagnosis status . The diagnosis is categorized in one of two ways on the basis of available diagnostic methods:

- Confirmed. The diagnosis has been made by an indisputable clinical finding (e.g., removal of larvae of tungiasis) or diagnostic test.

- Probable. The diagnosis is supported by evidence (including diagnostic testing) strong enough to establish presumption but not proof.

Expatriate. A person living in a destination with an independent residence and address and using the same infrastructure as local residents of the same economic class. Expatriates intend to remain in-country for ≥6 months and have no intention to legally change their citizenship or permanent residency status.

Main symptoms. The symptoms associated with the illness that was the reason for the clinic visit.

Migrant. A person who, at some time in their life, has emigrated from their country of birth and has previously or intends to legally change their citizenship or permanent residency status. The resident country is entered on the data collection form as the new home country.

Nonmigrant traveler. A person who is traveling for a purpose unrelated to migration.

Pretravel encounter. Any pretravel health visit or the receipt of travel-related health information.

Resident. A person who has their primary residence in a particular country.

Severity. The highest level of clinical care received for the travel-related diagnosis, including outpatient, inpatient ward, and inpatient intensive care unit (ICU) care.

Syndrome or system groupings of diagnoses. All GeoSentinel diagnoses are categorized into groups according to the type of syndrome or system affected ( Box 1 ).

Travel reason. Primary reason for travel related to the current illness ( Box 2 ).

Travel related. Designates the relation of the main diagnosis to the patient’s travel.

- Travel related. Used when the illness under evaluation, initially suspected to be travel-related, was determined to have been acquired during the patient’s travel.

- Imported infection. Used for infections acquired in the patient’s country of residence if exported to another country and then evaluated at a GeoSentinel site.

- Not travel related. Used when the illness under evaluation, initially suspected to be travel related, was determined to have been acquired before departure from or after returning to the home country.

- Not ascertainable . Used when the illness under evaluation, initially suspected to be travel related, was equally likely to have been acquired during the patient’s travel or before departing from or after returning to the residence country.

Changes to GeoSentinel Data Collection

During 2012–2021, multiple changes were made to the GeoSentinel data entry application ( Box 3 ). New fields and subfields that collect detailed information on patient types, diagnoses, and trip information were added to provide a complete profile of patients and their associated illnesses. Additional fields were added for diseases of interest to provide information (e.g., vaccination status, etiology [e.g., organism genus and species], and cause of death). Case definitions were developed for each diagnosis code, and data collection fields were refined on an ongoing basis to aid clinicians in classifying patients and diagnoses.

Internal validation is now used to ensure that data are collected uniformly and accurately among sites. The collection of diagnostic methods allows for validation of confirmed and probable cases, and quality assurance (QA) alerts prevent sites from classifying diagnoses as confirmed during data entry without required disease-specific diagnostic methods. Other QA alerts prevent the skipping of required fields as well as logical errors.

Before November 16, 2018, the variables of travel reason and exposure country (and region) were not linked to an individual diagnosis. Instances where patients had multiple unrelated diagnoses made it difficult to ascertain what information applied to which diagnosis. As a result, the data collection form and database were updated to specify travel reason and exposure country information for each individual diagnosis.

To fill knowledge gaps, enhanced surveillance projects were deployed throughout the analysis period to collect specific information about a disease or types of travelers that was not collected on the core data collection form. This included projects on antibiotic resistance for selected bacterial pathogens, rickettsioses, mass gatherings ( 13 ), rabies postexposure prophylaxis ( 14 ), planned and unplanned health care abroad ( 15 ), migrants ( 16 ), and respiratory illnesses related to COVID-19.

This report includes GeoSentinel data limited to unique patients with ≥1 confirmed or probable travel-related diagnosis who were evaluated after migration or travel at a GeoSentinel site in the United States during 2012–2021. Each patient might have multiple diagnoses. Patients must have been residents of the United States and evaluated after travel and within 10 years of migrating or returning from a trip outside of the United States. Only migrants with illnesses associated with their migration to the United States were included. The validity of diagnoses was verified by an infectious disease specialist using the diagnostic methods recorded by the sites. Descriptive analyses were performed on data from the 20 GeoSentinel sites in the United States ( Figure 2 ) with patients who met inclusion criteria. Frequencies were calculated on patient demographics (e.g., sex, age, country of birth, citizenship, and residence), travel-related information (e.g., reason for travel and country or region of exposure), diagnosis, diagnostic methods, year of illness onset, and severity of illness. Because of changes in the collection of travel-related information, a subanalysis was done on travel-related information before and after November 16, 2018. This information is reported separately. Geographic regions of exposure are classified based on modified UNICEF groupings ( https://data.unicef.org/regionalclassifications/ ). Data were managed using Microsoft Access (version 2208; Microsoft Corporation), and all analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute).

To demonstrate GeoSentinel’s ability to identify sentinel events and emerging disease patterns, three examples (i.e., dengue in Angola [2013], Zika in Costa Rica [2016], and yellow fever in Brazil [2018]) of emerging sentinel health threats that occurred during 2012–2021 are described. These health events were not limited to residents of the United States who were evaluated after travel and ≤10 years of migrating or returning from a trip outside of the United States. Therefore, these patients could be residents of any country and were seen at GeoSentinel sites both inside and outside of the United States.

During 2012–2021, a total of 198,120 unique patients were evaluated at GeoSentinel sites globally and included in GeoSentinel’s database ( Figure 3 ). Of these, 177,703 patients received at least one confirmed or probable travel-related diagnosis, of which 18,336 were reported from 20 GeoSentinel sites in the United States. Of the 17,538 patients evaluated by a clinician after travel, 17,389 were migrants or returning U.S. nonmigrant travelers to the United States, accounting for 25,973 travel-related diagnoses. The remaining 149 patients were non-U.S. residents and were excluded from the analysis. The results of migrants and returning nonmigrant travelers are reported separately.

Patient Demographics

Of the 17,389 patients who were included in this analysis, 7,530 (43.3%) were recent migrants to the United States; <1% of patients were expatriates. Of 7,527 migrants, 47.4% were female ( Table 1 ). The median age was 28.5 years (range = <19 years to 93 years), and the largest proportion of migrants was aged 19–39 years (35.9%). Of 4,672 patients with information available, 88.8% did not receive pretravel health information. Of 2,867 patients with information available on severity, a majority (89.8%) were seen as outpatients, 9.7% were seen in an inpatient ward, and <1% were seen in an ICU.

Of the 13,986 travel-related diagnoses among migrants, the most frequent were vitamin D deficiency (20.2%), Blastocystis (10.9%), latent tuberculosis (10.3%), strongyloidiasis (6.7%), and eosinophilia (5.8%) ( Table 2 ). A total of 43% of diagnoses fell into eight infectious or travel-related syndrome groupings including “other” (18.7%), gastrointestinal (15.7%), dermatological (2.0%), neurologic (1.9%), genitourinary (1.6%), febrile (1.5%), respiratory (1.5%), and musculoskeletal (<1%). No deaths or animal bites or scratches were reported ( Table 3 ).

Of the 2,614 diagnoses in the “other” grouping (Table 3), the most frequent were latent tuberculosis (55.2%), eosinophilia (30.8%), Chagas disease (3.8%), posttraumatic stress disorder (3.6%), and depression (2.9%). Of the 2,202 diagnoses in the gastrointestinal grouping, the most frequent were simple intestinal strongyloidiasis (41.6%), giardiasis (18.9%), Helicobacter pylori infection (8.4%), dientamoebiasis (6.9%), and schistosomiasis (6.5%). Of the 275 diagnoses in the dermatological grouping, the most frequent were fungal infection (42.6%), insect bite/sting (10.9%), rash of unknown etiology (10.2%), cutaneous leishmaniasis (5.8%), and leprosy (4.4%). Of the 263 diagnoses in the neurologic grouping, the most frequent were neurocysticercosis (76.8%), headache (16.4%), ataxia (1.5%), central nervous system tuberculosis (1.5%), and tuberculosis meningitis (1.1%). Of the 229 diagnoses in the genitourinary grouping, the most frequent were schistosomiasis (27.5%), chlamydia (15.3%), syphilis (11.4%), urinary tract infection (10.9%), and HIV (10.0%).

Among the 212 diagnoses in the febrile grouping (Table 3), the most frequent were malaria (25.5%), other extrapulmonary tuberculosis (13.2%), toxoplasmosis (8.0%), tuberculosis lymphadenitis (6.6%), and disseminated tuberculosis (5.2%). Malaria was diagnosed in 54 (<1%) migrants, and 88.5% did not receive pretravel health information (information available for 26 migrants). Of all species of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum was diagnosed most frequently (77.4%).

Among the 204 diagnoses in the respiratory grouping (Table 3), the most frequent was pulmonary tuberculosis (70.6%), which accounted for 68.9% of all active tuberculosis diagnoses; only 1% of migrants received a diagnosis of active tuberculosis disease. The remaining frequent diagnoses in the respiratory grouping were acute otitis media (4.9%), atypical pneumonia (3.4%), otitis externa (2.9%), and unspecified lobar pneumonia (2.9%). Of the 131 diagnoses in the musculoskeletal grouping, the most frequent were arthralgia (48.1%), trauma or injury (43.5%), osteomyelitis (1.5%), knee pain (1.5%), and sprain (1.5%).

Diagnostic Characteristics Before November 16, 2018

Among the 2,892 diagnoses with information available ( Table 4 ), the five most frequent regions of exposure were Sub-Saharan Africa (22.7%), the Caribbean (21.3%), Central America (13.4%), South East Asia (13.1%), and South Central Asia (9.2%). Among the 2,554 diagnoses with information available, the most frequent countries of exposure were Dominican Republic (7.9%), Thailand (6.5%), Haiti (6.2%), Ecuador (4.8%), and Myanmar (4.3%). Of 46 migrants with a malaria diagnosis, 89.3% were exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa (information available for 28 migrants).

Diagnostic Characteristics After November 16, 2018

Among the 2,012 diagnoses with information available (Table 4), the five most frequent regions of exposure were Central America (27.6%), Sub-Saharan Africa (26.2%), South East Asia (16.9%), the Caribbean (8.4%), and South America (7.0%). Among the 1,575 diagnoses with information available, the most frequent countries of exposure were El Salvador (11.2%), Thailand (10.7%), Honduras (9.1%), Guatemala (7.6%), and Dominican Republic (5.9%). Of seven migrants with a malaria diagnosis, all were exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa (information available for seven migrants).

Returning Nonmigrant Travelers

Among the 9,859 nonmigrant travelers returning to the United States, 55.7% were female and 75.3% were born in the United States. The median age was 37 years (range = <19 years to 96 years), and the largest proportion of nonmigrant travelers was aged 19–39 years (44.1%). Among the 8,967 patients with information available, 65.6% did not receive pretravel health information. Among the 5,884 patients with information available on severity, a majority (90.6%) were seen as outpatients, 8.4% were seen in an inpatient ward, and <1% were seen in an ICU. Approximately 1% of patients were expatriates, and 89.4% were U.S. citizens.

Of the 11,987 travel-related diagnoses of returning U.S. nonmigrant travelers (Table 3), 90.7% of diagnoses fell into nine infectious or travel-related syndrome groupings, including gastrointestinal (43.2%), febrile (16.7%), respiratory (13.0%), dermatological (8.9%), “other” (4.1%), animal bites or scratches (1.3%), genitourinary (1.4%), musculoskeletal (1.2%), and neurologic (<1%). The most frequent diagnoses (Table 2) were acute diarrhea (16.9%), viral syndrome (4.9%), irritable bowel syndrome (4.1%), campylobacteriosis (3.1%), and malaria (3.5%). Four deaths were reported, of which two were patients who received a diagnosis of severe P. falciparum malaria. Of the remaining two patients, one received a diagnosis of COVID-19 and the other received a diagnosis of acute unspecified hepatitis with renal failure.

Among the 5,173 diagnoses in the gastrointestinal grouping (Table 3), the most frequent were acute diarrhea (39.3%), irritable bowel syndrome (9.5%), campylobacteriosis (7.2%), giardiasis (5.5%), and chronic diarrhea (5.2%). Among the 2,001 diagnoses in the febrile grouping, the most frequent were viral syndrome (29.0%), malaria (21.0%), dengue (13.7%), chikungunya (6.4%), and unspecified febrile illness (5.0%). Among the 421 nonmigrant travelers with malaria of any species diagnosed, 80.8% had P. falciparum .

Among the 1,554 diagnoses in the respiratory grouping (Table 3), the most frequent were influenza-like illness (16.5%), upper respiratory tract infection (14.9%), acute bronchitis (11.9%), acute sinusitis (9.1%), and unspecified lobar pneumonia (8.4%). Among the 1,071 diagnoses in the dermatological grouping, the most frequent were insect or arthropod bite or sting (31.3%), rash of unknown etiology (8.8%), dermatitis (7.9%), skin and soft tissue infection (e.g., erysipelas, cellulitis, or gangrene [7.4%]), and superficial skin and soft tissue infection (6.0%). Among the 487 diagnoses in the “other” grouping, the most frequent were dehydration (18.7%), jet lag (17.9%), eosinophilia (11.7%), latent tuberculosis (8.8%), and anxiety disorder (7.6%).

Among the 173 diagnoses in the genitourinary grouping (Table 3), the most frequent were urinary tract infection (33.0%), schistosomiasis (11.6%), gonorrhea (9.3%), pyelonephritis (8.7%), and genital chlamydia (8.1%). Among the 142 diagnoses in the musculoskeletal grouping, the most frequent were arthralgia (19.7%), fracture (17.6%), myalgia (10.6%), trauma or injury (9.9%), and contusion (7.8%). Among the 105 diagnoses in the neurologic grouping, the most frequent were headache (26.7%), vertigo (12.4%), acute mountain sickness (10.5%), neurocysticercosis (9.5%), and dizziness (8.6%). Among the 153 diagnoses of bites or scratches, the most frequent were dog bite (50.3%), monkey bite (18.3%), other animal bite (6.5%), monkey exposure (5.9%), and dog exposure (3.9%).

Among the 9,919 diagnoses, 6,518 had information regarding travel reason ( Table 5 ). The most frequent reasons for travel were tourism (44.8%), VFR (22.0%), and business (13.4%). Among the 6,296 diagnoses with information available, the five most frequent regions of exposure were Central America (19.2%), Sub-Saharan Africa (17.7%), the Caribbean (13.0%), South East Asia (10.4%), and South America (9.4%). Among 5,920 diagnoses with information available, the most frequent countries of exposure were Mexico (12.5%), India (7.2%), Dominican Republic (5.3%), China (3.3%), and Costa Rica (3.0%).

Of 300 nonmigrant travelers with malaria, 70.3% were VFRs (information available for 232 nonmigrant travelers), and 88.6% were exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa. Of 163 VFRs with malaria, 70.2% did not receive pretravel health information (information available for 141 nonmigrant travelers), and 88.3% did not take malaria chemoprophylaxis (information available for 103 nonmigrant travelers).

Information regarding travel reason and exposure region was available for all 2,068 diagnoses (Table 5). The most frequent reasons for travel were tourism (53.6%), VFR (21.4%), business (12.3%), and missionary (6.2%). The five most frequent regions of exposure were Sub-Saharan Africa (25.5%), Central America (17.3%), South East Asia (11.2%), the Caribbean (10.9%), and South Central Asia (9.0%). Among the 1,894 diagnoses with information available, the most frequent countries of exposure were Mexico (13.2%), India (5.0%), Dominican Republic (4.2%), Philippines (3.0%), and Ethiopia (3.0%).

Of 121 nonmigrant travelers with malaria, 57.9% were VFRs and 95.9% were exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa. Of 70 VFRs with malaria, 83.3% did not receive pretravel health information (information available for 54 nonmigrant travelers), and none took malaria chemoprophylaxis (information available for three nonmigrant travelers).

Dengue in Angola, 2013

During April–May 2013, GeoSentinel sites in Canada, France, Germany, Israel, and South Africa reported 10 cases of dengue among travelers returning from Luanda, Angola. All patients had classic symptoms of dengue that included headache and joint pain and recovered without complication. Although dengue is endemic in Angola, before 2013, the last outbreak occurred during the 1980s. In the decades that followed, little was known regarding the epidemiology of dengue in Angola because of poor surveillance ( 17 ).

Although six cases of dengue had been reported to the Ministry of Health of Angola by April 1, 2013, the GeoSentinel cases, in combination with other imported cases to Portugal, were among the first indications of a large-scale outbreak. By May 31, there were 517 suspected cases and one death reported; all but two cases were in Luanda province ( 18 ). The GeoSentinel cases in Angola demonstrated that data on travelers’ adverse health events can aid in the detection of outbreaks, offering insight into the epidemiology of infectious disease in countries with suboptimal surveillance and reporting.

Zika in Costa Rica, 2016

On January 26, 2016, a GeoSentinel site in Massachusetts diagnosed dengue in a returned U.S. traveler from Nosara, Costa Rica. The patient returned to the United States with fever, rash, conjunctivitis, arthralgia, and headache; the patient also reported multiple mosquito bites. The patient was referred to a GeoSentinel site where antibody tests for Zika and dengue viruses were conducted by CDC. Plaque reduction neutralization antibody testing confirmed a diagnosis of Zika ( 19 ).

Zika virus emerged in the western hemisphere during 2014–2016 when outbreaks were reported from certain countries in the Americas and Caribbean ( 20 ). This case was the first case of Zika reported from Costa Rica, illustrating the continual geographic spread of a high-consequence pathogen. The Massachusetts GeoSentinel site detected and reported this sentinel case, and it also sent a networkwide notification, alerting clinicians to the risk for Zika in Costa Rica, a popular travel destination with no previous evidence of underlying circulation. By August 2017, a total of 1,920 cases were reported in Costa Rica, mirroring the trends of other countries in the region.

Yellow Fever in Brazil, 2018

In January 2018, a GeoSentinel site in the Netherlands reported a case of yellow fever in a Dutch man aged 46 years with recent travel to São Paulo state, Brazil. He had signs and symptoms of diarrhea, fever, headache, myalgia, and vomiting. By March 15, 2018, four additional GeoSentinel sites reported cases of yellow fever among travelers returning from Brazil, including two deaths. These five cases accounted for one half of all cases reported among international travelers to Brazil during this time. All patients were unvaccinated travelers, many of whom visited Ilha Grande ( 21 ).

Although yellow fever is endemic in Brazil, during 2016–2017 and 2017–2018, a higher incidence does not, by itself, indicate geographic expansion ( 22 ). Cases detected by GeoSentinel in early 2018 were among the first reported in newly identified regions of risk, confirming travelers as sentinels in the expansion of the outbreak and highlighting the importance of yellow fever vaccination in recommended regions ( 21 ).

GeoSentinel is the only surveillance network that operates a global, provider-based emerging infections sentinel network to conduct surveillance for travel-related infections and communicates with public health and clinical partners ( 11 ). From its inception in 1995 to 2011 ( 11 ), efforts were made to increase the size of the network, modernize data collection, and introduce internal validation to improve the quality of the data collected. Since 2012, GeoSentinel has expanded to 71 sites on six continents and has generated approximately 70 peer-reviewed publications. GeoSentinel also has undergone numerous methodologic changes aimed to improve data collection, the validity of resulting conclusions, and the provision of public health recommendations.

GeoSentinel data have been instrumental in the detection of sentinel events, as demonstrated by, but not limited to, the detection of expanded geographic area of yellow fever in Brazil ( 21 ), a large outbreak of dengue in Angola ( 17 ), and the first case of Zika in Costa Rica ( 19 ). These examples illustrate GeoSentinel’s ability to both identify emerging pathogens and communicate findings with clinicians and public health professionals around the world.

The most frequent diagnoses among migrants described in this analysis (e.g., vitamin D deficiency and latent tuberculosis) have been described elsewhere ( 23 , 24 ). Vitamin D deficiency might be because of reduced sun exposure caused by skin-covering clothing as well as low dietary intake ( 23 ). Acquisition of strongyloidiasis and latent tuberculosis might be from crowding, malnutrition, exposure to unsafe food and water, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to health care ( 25 ). Multiple presentations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (e.g., pulmonary, extrapulmonary, lymphadenitis, disseminated, CNS tuberculoma, and meningitis) also were reported among migrants, highlighting that health care professionals should maintain a high degree of suspicion for M. tuberculosis infection among ill patients whose routine bacterial cultures do not yield a pathogen. Because the United States has the largest population of migrants in the world ( 26 ), health care professionals should continue to advocate for medical care for this underserved population, with the aim to prevent disease reactivation and subsequent spread to and within vulnerable populations.

Gastrointestinal illnesses remain a frequent cause of illness among travelers ( 27 ). In this analysis, acute diarrhea was the most frequent illness among nonmigrant travelers, accounting for 16.9% of their diagnoses. Previous studies have reported attack rates for acute diarrhea among travelers ranging from 30%–70%, most often caused by bacterial pathogens and transmitted because of poor hygiene practices in local restaurants ( 28 ). In other studies, travelers have reported not adhering to prevention practices and drinking unsafe tap water, consuming drinks with ice, eating salads, and consuming unpasteurized dairy products while abroad ( 29 ). Most acute diarrhea cases reported to GeoSentinel were of unknown etiology, illustrating the lack of use of specialized diagnostic tests or culture to determine the cause of diarrhea ( 30 ), despite the widespread availability of multiplex polymerase chain reaction tests for gastrointestinal pathogens ( 31 ), likely because the majority of cases of acute diarrhea resolve without the need for intervention ( 32 ).

Febrile illnesses were another frequent cause of illness among nonmigrant travelers in this analysis, of which viral syndromes and P. falciparum malaria were most frequent. Of nonmigrant travelers with malaria, a majority were exposed in Sub-Saharan Africa; the majority were VFRs, who infrequently received pretravel health advice or took malaria chemoprophylaxis. Inadequate pretravel preparation practices place VFRs at high risk for acquiring malaria during travel. Studies of African VFR travelers indicated they might not be able to afford health care visits, might feel unable to advocate for themselves in a health care setting, and might be culturally opposed to malaria chemoprophylaxis or other preventive measures (e.g., use of bed nets) because of concerns about offending their hosts or a low perception of risk ( 33 , 34 ). CDC recommends that all travelers going to an area where malaria is endemic take chemoprophylaxis before and during travel ( 35 ), but special considerations (e.g., improving accessibility or improving trust in the U.S. health care system) could be prioritized to ensure that VFRs are protected from malaria ( 33 , 36 ).

COVID-19 Pandemic

During 2020–2021, the number of patients presenting at U.S. GeoSentinel sites substantially decreased, mirroring worldwide declines in travel because of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated travel restrictions. Although GeoSentinel historically has been lauded for its ability to detect sentinel events in real time, GeoSentinel only retrospectively identified cases of influenza-like illness as COVID-19 among travelers who returned from China early in the pandemic. Although the outbreak began in China, a popular destination for U.S. travelers, in late 2019, U.S. GeoSentinel sites first reported COVID cases among travelers in March 2020. This lack of early identification of COVID-19 cases was likely because of three main reasons. First, daily reports were generated for assistance in detecting sentinel events, but these were simple line listings of cases and focused primarily on etiologic diagnoses; although cases of “viral illness” were reported from China to GeoSentinel as early as December 2019, these were not identified to be out of the ordinary. Surveillance systems (e.g., GeoSentinel) are most effective in detecting established etiologic illnesses, not novel pathogens ( 37 ). Second, delays in identification and available diagnostics for this novel pathogen meant that testing was not routinely available globally or at GeoSentinel sites early in the pandemic; therefore, etiologic COVID-19 diagnoses were only made retrospectively. Third, many cases of COVID-19 might have had mild symptoms similar to influenza, the common cold, and seasonal allergies, whose symptoms can be treated with over-the-counter medication. Thus, ill travelers might have opted to treat their symptoms at home and not seek health care or visited their primary care provider instead of a travel and tropical medicine site despite their recent travel.

To address these challenges, GeoSentinel has begun to explore other ways to detect and track novel pathogens more rapidly. GeoSentinel is developing automated, real-time data analytics (e.g., machine learning algorithms by likelihood of outbreak origin) to improve the ability to detect outbreaks and unusual clusters of disease together with more classical surveillance approaches ( 38 ).

The findings in this report are subject to at least six limitations. First, GeoSentinel data are not representative of all travelers. Although GeoSentinel tracks illnesses among travelers who are treated at GeoSentinel sites, data are entered at the discretion of the sites, which might lead to underreporting. Second, sites are not evenly dispersed globally and are predominantly located in Europe and North America. This pattern might reflect the travel attributes of persons from these continents. Third, GeoSentinel only collects data on ill travelers who seek care at GeoSentinel sites. The total numbers of travelers, ill travelers who do not seek care, or travelers who seek care outside of the GeoSentinel network is unknown. Thus, GeoSentinel data cannot be used to estimate risk, incidence, prevalence, or other rates because the number of well or unexposed travelers in the denominator is not known. Fourth, the United States does not have many large travel and tropical medicine centers (in comparison with Europe or Asia) and travelers, including migrants, might seek care external to the GeoSentinel network. Fifth, although changes in the information collected, methods, and the sites themselves have made data collection more robust, these changes also make the comparison of periods difficult and, in certain cases, inappropriate. Although all sites use the same standardized data collection form, data entry practices vary by site and over time. Finally, the large number of migrants reported from U.S. GeoSentinel sites might be the result of selection bias because of the migration medicine specialization of many U.S. sites. Diseases detected among migrants might be driven by routine screening on entry to the United States.

As of September 2021, GeoSentinel has incorporated research through its cooperative agreement between CDC and ISTM. This will allow GeoSentinel to conduct hypothesis-driven studies to help guide clinical and public health recommendations. Initial projects include investigation of fever of unknown etiology among travelers, neurocognitive outcomes among travelers with malaria, kinetics of human Mpox infections, and exploration of the distribution and types of antimalarial resistance using malaria genomics.

Over the past decade, GeoSentinel has contributed to the early detection of diseases among international travelers. The information about demographics, traveler types, and frequent diagnoses provides data that clinicians and public health agencies can use to improve pretravel preparedness and enhance guidance for the evaluation and treatment of ill travelers who seek medical care after international travel. The key successes and shortcomings of GeoSentinel serve as references to improve surveillance and expand the capability to detect sentinel events.

The following active members of the GeoSentinel Network contributed data from U.S. sites: Susan Anderson (Palo Alto, California); Kunjana Mavunda (Miami, Florida); Ashley Thomas (Orlando, Florida); Henry Wu (Atlanta, Georgia); Johnnie Yates (Honolulu, Hawaii); Noreen Hynes (Baltimore, Maryland); Anne Settgast, Bill Stauffer (St. Paul, Minnesota); Elizabeth Barnett (Boston, Massachusetts); Christina Coyle, Paul Kelly, Cosmina Zeana (Bronx, New York); John Cahill, Marina Rogova, Ben Wyler; (New York, New York); Terri Sofarelli (Salt Lake City, Utah). All maps were contributed by Marielle Glynn.

Corresponding author: Ashley B. Brown, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Disease, CDC. Telephone: 678-315-3279; Email: [email protected] .