- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

The Science of Sport

Scientific comment and analysis of sports and sporting performance

Tour de France 2009: Power estimates

Ross · 14 Jul 2009 ·

Last updated on December 2nd, 2022 at 09:54 pm

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

The Tour is currently winding its way through France, in what is another pretty sedate and routine stage so far. It’s looking like a sprinter’s stage, and maybe the battle for green between Cavendish and Hushovd.

To pass the time, I thought I’d do a post on the power outputs of elite cyclists in the mountains, which is always a nice topic of discussion, especially among those of you who measure power output and enjoy comparing yourself to the pros. So perhaps the numbers below will put into perspective just what it takes to ride at the front of a race like the Tour!

It’s also a post that was partly inspired by some of your comments in response to our race report from Friday's racing up to Arcalis , the Tour’s first mountain stage.

In that post, I commented that the climbing time of the lead group was around 25:22 (for Contador, 25:43 for the rest), compared to the time of 22:55 when Jan Ullrich won on the same climb back in 1997. Many of you suggested that this slowing of the times was an indication that the Tour is “cleaner” now – the fight against doping is being won, and the slower times are the outcome of having fewer doped riders pumping the pedals powered by all manner of EPO, GH, Insulin, testosterone and who knows what else! That’s the thinking, anyway…The same question and debate seems to be doing the rounds in a few chat forums on the Tour , so it’s obviously topical.

So today’s post is a look back on the Tour, and just how fast it used to be. Unfortunately, I don’t have data that span the most important period (2002 to 2006), but it does provide a good starting point for the debate, and a topic of discussion while the Tour rolls over the flatlands before the next big rendevous in the French Alps this weekend.

Is leTour 2009 “clean”? …too early to tell, too many confounders

To begin with, it’s too early to answer the question definitively. There are simply too many confounding factors that can’t be controlled – the weather, the temperature, the race tactics, the quality of the riders, the race situation – all these things impact on the estimated power output, and given that we’ve only really seen about 2km of all-out racing on the climbs, it’s impossible to infer too much.

For example, if you compared the climb of the Tourmalet on Sunday to the climbs during the period 1995 to about 2006, you’d find an enormous difference – the Tourmalet has rarely been climbed so slowly. But that tells us nothing of the doping situation, but rather the stage profile, with 70km of riding after the summit negating the climb. So one must be careful to avoid the trap of looking at the numbers blindly and in isolation.

I think that if we look back on the 2009 Tour in a few years, it will make interesting reading though. Over a period of years, and maybe 15 to 20 climbs, it starts to become more meaningful to compare times and power outputs, because factors like tactics and weather start to “wash” out and trends become more meaningful than isolated observations.

So let’s begin with a dose of realism – Contador and co may have climbed 3 minutes slower than Ullrich on Arcalis, but that ALONE doesn’t tell us too much. There are however other factors that contribute to the argument, and we’ll get to those shortly.

First, let’s look at the power outputs that have been estimated for pros on the major climbs of the Tour in the past. Remember of course that all the above “confounders” or limitations exist for this analysis as well, but by looking long-term, at trends, we can still gather useful information, as I explained above. But race context, environment, strategy – all these things affect it, and I’m well aware of this limitation. I do however maintain that taking a long term view allows interesting trends to emerge, despite the limitations. The mistake would be to zone in on specific climbs, but that’s not what this is about!

Power output on major climbs – the Tour champions over the years

Below is a graph showing the estimated power output * for the eventual Tour winner on the final climb of the Tours between 1989 and 2001 . In other words, in 1989, Greg Lemond would go on to win the Tour, and what has been done here is to estimate his power output on the final climb of each mountain stage and then average them for that year. Same for Lemond in 1990, then Indurain, Riis, Ullrich, Pantani and Armstrong.

Note that for all years, the power output has been “normalized” by expressing it relative to body weight . This is important, because Indurain, for example, was much larger than Pantani. Pantani at a power output of 350W was thus the equivalent of Indurain riding at around 500W. So, to compare them, one either has to express power output per kilogram, or express it for a standard weight. I’ve taken the approach of expressing it relative to body weight. I’ll post more on the effect of body weight on performance in the mountains once we get closer to Mont Ventoux.

Also, just as an addendum to the post in response to a comment by Will below, I must make the point that all the ABSOLUTE power outputs were calculated using the rider mass PLUS the mass of the equipment (bike and gear, assumed at 9kg for calculations), and then expressed relative to rider weight (see footnote).

It makes for some interesting reading – Greg Lemond averaged 5.7 W/kg on the final climbs during both his Tour wins. Then Indurain started off with an average power output of 5.3 W/kg, followed by 4.91 W/kg, and then it began to climb, so much so that when Indurain won his fifth Tour in 1995, his average power output on the final climbs of the mountain stages was an incredible 6.35 W/kg. (Just to labour the point – if you want to work out the ABSOLUTE power output for each rider, just multiply the power I’ve shown by the rider’s mass. For Indurain, multiply by 80kg and you get a value of 508W)

That high power output was maintained for the next four years, Riis averaged 6.47 W/kg, Ullrich 6.33 W/kg, and then Marco Pantani set the ‘record’ when he averaged 6.63 W/kg during the 1998 Tour.

In 1999, which was the year after the big Festina scandal, the power output decreased to 5.88 W/kg, and then it began a progressive climb in 2000 and 2001, so that it was back up to 6.3 W/kg in 2001. That, unfortunately, is where the data I have end – see the footnote below.

However, we do know that Lance Armstrong’s power output on Alp d’Huez in 2004 was calculated as 495W – this was presented as a scientific paper at the ACSM congress in Nashville in 2005, and I noticed the power output. It equates to 6.97 W/kg (as shown in the graph). It must be noted that this was the time-trial stage and so the climb was performed without other climbs and a day of racing before, and so should be slightly higher. However, what’s really interesting to note is that even with this apparent “freshness”, Armstrong still only rode 25 seconds faster in the 2004 climb than in 2001, when he won atop the Alp as well (after a long stage). The effect of the fatigue exists, but it’s not as profound as I think one first imagines…

Whether the power output was as high as this on other climbs between 2002 and 2007, I’m not sure – if you look at a list of the best times ever recorded on these climbs, you’ll find that many were set in this era from 2002 to 2007. Pantani still holds most of the records, but the generation 2002 to 2007 are in amongst the best times, faster than Riis and Ullrich, and so I suspect that the power outputs during this period as comparable to those achieved in the period 1994 to 1998, and 2000 to 2001 . Therefore, the power output from 2002 to 2005 at least will be in the same range – 6.3 W/kg or higher. If you have the climbing times, do let me know.

To unpack the graph above in a bit more detail, the table below shows the power output estimated for Lance Armstrong during his three Tour wins in this recording period (1999 to 2001):

What does it take to ride the Tour?

There are a number of ways to interpret these numbers. First of all, it puts into perspective the enormous power output required to be competitive in the pro-peloton in the mountains. Take any of the above riders, and you’ll find that you have to be able to sustain a power output well above 6W/kg. Greg Lemond, and Miguel Indurain’s first few Tours were won with power outputs lower than this, but ever since, anything less than 6W/kg is not high enough.

In fact, since the mid-90s, 6.2 W/kg seems to be the minimum requirement , apart from the “aberration” of 1999 when the Tour was on full alert after the fiasco of 1998 and Festina-gate. Physiologically speaking, riding at 6.2 W/kg for up to 40 minutes is quite extra-ordinary. Elite athletes are usually able to sustain power outputs between 80% and 90% of maximum for a prolonged time. If a rider is able to sustain a power output of 6.3 W/kg for 30 minutes, then you can infer their peak power output will be somewhere between 7 and 7.5 W/kg, incredibly high.

If you are a cyclist who monitors your own power output, then, work out what 6.3 W/kg means for you (say, 520 W), and next time you are riding on a slope of about 7 to 9%, try to hold that power output for as long as possible. It is an eye-opener, that is for sure.

The doping implication

I’m sure most of you reading this have already made the junction and are asking what is physiologically possible? That is, Greg Lemond was down at 5.7 W/kg, then within 5 years, the power output has climbed by 10%, and then continued to climb, so that Marco Pantani is 15% higher than Lemond. That level of progress is not typical of mere physiology, so it does point to something, and that “something” of course, is doping. Or is it? Perhaps we should be expecting sustainable power outputs of 6.3 W/kg?

I do have to point out the following though – remember that these power outputs are estimated based on time. Therefore, technological changes such as a reduction in the weight of the equipment, stiffer bikes (as pointed out by a commenter), and better components will make a difference to estimated power output , even though the caliber of riders haven’t changed at all. Part of the changes you see in that graph can therefore be attributed to changes in technology.

The question is how much does technology explain? That depends what you want to believe, unfortunately! If you want to believe that cycling is clean, or rather, was clean right up to and after the Armstrong era, then you’ll say that technology accounts for a 10% improvement. That would mean that the power outputs of 2001 are “expected”. Put differently, this argument says that Lemond on the same equipment would also be producing 6.3 W/kg.

Others would say that technology contributes little to this growth. I don’t know the answer, but I do think that the impact of technology has been overstated and that the greatest reason for the change you see in that graph is doping. Yes, bikes are lighter, stiffer and therefore times should improve. But, at the same time, we know that Riis, Ullrich and Pantani have all been implicated (or straight out confessed), and so their performances are likely drug aided. Therefore, the fact that Riis, Ullrich and Pantani achieved such high power outputs relative to Lemond is an indication that either:

- The drugs don’t work and technology really is responsible for all of the increase

- The drugs do help and the technology is not that big a factor after all.

Of course, this itself assumes the these riders were doping, but I think it’s pretty reasonable to say that, in hindsight. So my interpretation of the above graph is that in the 1990s, the Tour moved into a new era, where doping characterized performance, and that era peaked in the mid-90s.

The doping ‘fingerprint’ on performance

I read an article this week, for example, that reports that when the test for EPO was developed, samples from the 1998 and 1999 Tour were used to ‘test the test’, and 80% of them were found to be positive! The poor researchers thought something was wrong with their assay, because so many samples were being found to contain EPO. There is little doubt that until that test was finally perfected for 2000, EPO abuse was rife in the peloton. The graph above spans that period nicely.

Post 2000, all indications are that the peloton went “back to basics” and blood doping, which is arguably less effective, if only because of practical difficulties around doing it. One would expect the sudden “removal” of EPO to cause a drop in pace in the peloton, of course, while riders used what they could until the teams had figured out how to bypass the systems once again.

The interesting year is 1999 – that was the first year after the Festina scandal, and the Tour was on high alert. I remember police raids of team hotels, and a general crackdown. Not from the UCI or Cycling authorities, mind you, but from the police. So I think the lower speeds of that year were a function of greater policing, quite literally! Then, after that, the speeds just go back up again, as shown in the graph.

Cyclists may have occasionally been forced to regroup and think of how to use drugs without being caught, but they rarely stop because of the risk…Here, I think of Bernard Kohl , who has just recently highlighted just how ineffective testing is (including the passports), by his admission that for years, he used everything – Growth hormone, insulin, EPO, testosterone and blood doping, without being caught .

Now, the really interesting thing – if the mid-90s were characterized by doping and those performances are “assisted”, then one cannot help but notice that the late 90s and early 2000s have produced similar performances, taking into account the short-term drop in 1999. Since that, it’s been a steady climb upward, and it would be very helpful to see what the performances of 2002 – 2005 are like, so if you have them, let me know.

There are then only two ways to explain the performances from 1999 to 2001 (and beyond, since they will remain similar, or be even better). One is that must believe that one rider is genuinely better than the effect of doping. Or, alternatively, you are left with the conclusion that his performances are an extension of what went before…

Unfortunately, no amount of evidence will prove which it is. Based on this evidence ALONE, I must confess that I would not deliver a verdict either way. You may be the judge…

Looking ahead

All of this is interesting, and hopefully food for thought. It doesn’t exactly help us answer the question of “Is the 2009 Tour ‘clean’?”. That too, I’m afraid, is unanswerable as far as performance-analysis goes.

However, it does lead into the next post, which is a more subjective view of the performances in the last two years in the Tour, and what is my opinion on the state of the peloton. But that is for tomorrow!

* Note : The method used for all the above estimations comes from a publication from Polar France, performed by two French scientists: Antoine Vayer and Frederic Portoleau. It was published in 2002, and called “Pouvez-vous gagner le Tour?” , and it was kindly given to me by David Walsh (yes, that one). The method used was to calculate power output given the riding time, the mass of the rider PLUS equipment, and then all the factors that are typically used (rolling resistance, frontal surface area, air density, gravity, and speed). I’ve expressed that calculated power relative to body weight.

You’ll find a number of different methods to estimate power, but all produce relatively similar values – there is some error though, which explains slight differences between these and other similar estimates. The important thing is consistency in the method, at least in as far as comparing years goes. Unfortunately, the book was published in 2002 (by PolarFrance.fr), and so I don’t have the same method to work out the power output from 2002 to 2008. That would be very revealing, I believe. An analysis presented at the ACSM conference in 2005 estimated Armstrong’s power output on Alpe d’Huez at 495W.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

How Fast Do You Have to Climb to Win the Tour de France - And Other Bike Racing Questions Answered

You know it's really fast, but this is how to tell whether you have a shot at hanging with the pros.

Gear-obsessed editors choose every product we review. We may earn commission if you buy from a link. How we test gear.

How strong of a climber do you have to be to win the Tour de France?

The other metric—watts per kilogram of body weight—is more closely watched, because environmental factors play a lesser role. In both cases, the measurements are most meaningful on summit finishes that take top riders 30 minutes or more (which means we’re measuring a rider’s peak output at threshold). So what’s it take to win? A lot.

On major climbs at the 2016 Tour, the top riders produced VAM ranging from 1,500 to 1,650 meters per hour—that’s almost half a vertical meter per second (a well-trained amateur rider is more likely to achieve somewhere around 1,000 m/h). Watts per kg has fluctuated over the years. Lance Armstrong, at the height of cycling’s doping era, is said to have produced as many as 7 w/kg on long climbs. Today, riders pump out quite a bit less. An analysis by Mike Puchowicz, a doctor and coach in Mesa, Arizona, who does performance modeling, suggests that top riders’ sustained power outputs for long climbs in the Tour during the past eight years have ranged from 5.5 to 6.3 w/kg. By contrast, a well-trained amateur racer might be able to manage 4 w/kg, while a recreational rider might gasp his or her way to 2.5 w/kg.— Joe Lindsey

Get some tips on how to climb smarter:

How can you tell if a breakaway will survive?

It’s tough to say—the teams in the peloton have various motivations to chase, let the break go, or even slow down, says Cannondale-Drapac directeur sportif Tom Southam. But you can make an educated guess: Chapatte’s law (named for former pro racer and TV broadcaster Robert Chapatte) states that a breakaway rider needs 60 seconds for every 10 kilometers left in the race to stay away. It’s not always accurate, but that uncertainty is what makes bike racing so entertaining.— Jen See

How was cyclocross invented?

According to the new book Rainbows in the Mud: Inside the Intoxicating World of Cyclocross by Paul Maunder, the sport traces its roots to the late 19th century, when a French soldier started riding his bike “cross-country in order to keep up with the horse-bound general he was supposed to be looking after.” Soon whole battalions of French troops were being trained to ride bicycles off road. Military training morphed into sport, and France held its first cyclocross national championship in 1902, with Belgium following suit in 1910 and the US in 1963.— J.S.

RELATED: 8 Things to Know About Cyclocross National Championships

What was the first-ever bike race?

It’s tough to pin down, says David Herlihy, author of Bicycle: The History . While newspapers of the era contain accounts of earlier, more informal races, the most common citation is a May 31, 1868 race of 1,200 meters in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Cloud, won by Irishman James Moore. The claim is questionable, because Moore’s field wasn’t the first to race that day. Still, Herlihy argues that the four heats at Saint-Cloud were the first legitimate races, thanks to the fact that they were pre-announced as a competition and awarded prizes.— J.L.

What’s the fastest someone has ridden under their own power?

The International Human-Powered Vehicle Association keeps tabs on the world’s fastest human efforts. It reports that on September 17, 2016, aerospace engineer and AeroVelo cofounder Todd Reichert pedaled a fully enclosed, aerodynamic speedbike a record 89.59mph in Battle Mountain, Nevada. Shaped like a missile, the AeroVelo Eta sped along on two wheels, propelled by a giant chainring and Reichert’s legs—just like the bicycles we know and love, but much, much faster.— J.S.

.css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#F8D811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} Racing

Derek Gee Claims First Professional Victory

Riders Complete Unbound on Walmart Beach Cruisers

Tough Day at Unbound for Van Avermaet and Mohorič

Lachlan Morton and Rosa Klöser Win Unbound 200

Thymen Arensman Gains 10 lb While Racing the Giro

BORA-hansgrohe on Van Aert, Pidcock Rumors

Ivar Slik in Critical Condition after a Crash

2024 Critérium du Dauphiné: How to Watch & Preview

Lael Wilcox Embarks on 18,000-Mile Cycling Journey

2024 Tour of Somerville | Results & Highlights

2024 Easton Twilight Crit Results & Highlights

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

IDEAS & TRENDS

Super, Sure, but Not More Than Human

By Gina Kolata

- July 24, 2005

THE urban legends about Lance Armstrong have been circulating for years: He's superhuman, a genetic freak, the one person on the planet so perfectly made to ride the Tour de France that competitors don't have a chance. The mythmaking only increased last week as Mr. Armstrong headed toward Paris in pursuit of his seventh consecutive victory in the tour, a feat unmatched in the history of cycling.

Edward F. Coyle, an exercise physiologist at the University of Texas who studies Mr. Armstrong in his human performance lab, saw the hype machine in action a few years ago. Bicycling magazine visited the lab during a testing session.

"We noted that his blood lactic acid levels were low," said Dr. Coyle, who is a cyclist himself. That is often interpreted to mean that an athlete does not tire easily. "Within five days of Bicycling magazine visiting my lab, before their article was even published, there were Web sites reporting that Mr. Armstrong had the lowest lactate levels ever recorded and that he was superhuman," he said.

But is Lance Armstrong that unusual? It depends on whom you compare him with.

Mr. Armstrong, for example, can maintain a power output of about 6.8 watts per kilogram of body weight for 20 minutes. "I would say there are probably no more than 20 people on earth with that ability, and probably at least 10 of them rode or are riding in the Tour de France," Dr. Coyle said.

But are Mr. Armstrong and these other elite cyclists so different from each other that if you gave an exercise physiologist anonymous power output data and other parameters like VO2 max, a measure of how efficiently oxygen is delivered to muscles, the scientist could pick who would win the tour?

"Unfortunately, no," said Michael Berry, an exercise physiologist and cyclist at Wake Forest University. Science, he said, does not know enough about the complex interplay of physiology and performance, and there are factors that no one knows how to measure.

For example, those who recover quickly from arduous rides can have an advantage in the tour, which goes on for three grueling weeks with the racers covering up to 150 miles each day. "As far as I'm aware, research has not looked at that," Dr. Berry said. "What variable would you look at? Would you measure VO2 max after they've had an exhaustive exercise bout? Are you going to look at a biochemical marker in the blood?"

Richard Coast, an exercise physiologist and cyclist at Northern Arizona University, agreed.

"When you look at elite athletes, cyclists or marathoners, you have to have the physiology to get to that point," he said. "But then, if you looked at the top half-dozen, you really couldn't tell the difference."

So the legends spread as a way of explaining why one person wins consistently. It happened with Miguel Indurain, a Spaniard who won five consecutive tours in the 1990's. Mr. Indurain's VO2 max, according to a widespread rumor, was 95 milliliters per kilogram of body weight per minute, a level so high it is unheard of. The real number was 78, Dr. Coyle said, but researchers who tested Mr. Indurain were reluctant to put the true figure in their paper for fear of demolishing the Indurain myth.

In the case of Mr. Armstrong, Dr. Coyle has the true figures and they are impressive, although not superhuman. Mr. Armstrong publishes his vital statistics on his Web site: resting heart rate, maximum heart rate, lactic acid threshold and other measures like watts of power during endurance rides, an indicator of how fast he can ride for hours on end.

Mr. Armstrong's numbers may not be much different from other elite racers, but he has the average cyclist beat by a mile. A good recreational rider could generate about 4 watts per kilogram, which would translate to a speed of about 20 miles an hour on a flat road. Mr. Armstrong, Dr. Coyle said, would be traveling at 34 miles an hour.

"The average recreational cyclist could not get up to 34 miles an hour and if you launched them at 34 miles an hour, let them latch onto a car, say, and then let them go and said, 'O.K., keep it,' they could not hold that speed for more than 5 or 10 seconds," Dr. Coyle said.

Mr. Armstrong's VO2 max is 85 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute. An average untrained person has a VO2 max of 45 and with training can get it to 60.

"Lance would be 60 if he was a couch potato and never trained," Dr. Coyle said. "For the average person, their ceiling is Lance's basement."

"I'm sure there are other Lances out there who have the same potential," he added. But they may not know it because they never tried to train. "They could get on a bicycle right now," he said, "and if they were willing to suffer they could ride with the average person who's been training for two years."

Training can make a huge difference to those who are genetically gifted. Mr. Armstrong, for example, had a lactic acid test after he had recuperated from cancer and had just begun to train again. He had 8 millimoles of lactate per liter of blood. The average person has a value of 12. But after Mr. Armstrong trained, his levels were 6, an astonishingly low number. "He has to train hard to have those very, very low levels," Dr. Coyle said.

Dr. Coyle said the difference between Mr. Armstrong and many of his competitors may be focus and training techniques. He said there were at least 10 cyclists in this year's tour who were potential challengers.

"If they followed Lance's preparation and rode on his Discovery team with the same great teamwork that Discovery has given him, and if they can muster the right mindset to believe they can really do it when it counts, they could be equally impressive," he said.

Cycling Around the Globe

The cycling world can be intimidating. but with the right mind-set and gear you can make the most of human-powered transportation..

Are you new to urban biking? These tips will help you make sure you are ready to get on the saddle .

Whether you’re mountain biking down a forested path or hitting the local rail trail, you’ll need the right gear . Wirecutter has plenty of recommendations , from which bike to buy to the best bike locks .

Do you get nervous at the thought of cycling in the city? Here are some ways to get comfortable with traffic .

Learn how to store your bike properly and give it the maintenance it needs in the colder weather.

Not ready for mountain biking just yet? Try gravel biking instead . Here are five places in the United States to explore on two wheels.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Tour de Lance

Lance Armstrong is obsessed with numbers: He measures his seat height by the millimeter, his food by the gram, and his performance by the watt. Such attention to detail is de rigueur in cycling, one of the most data-driven sports of all. Consider the numbers behind the Tour de France: 21 days of riding; 2,110 miles; 5,200 calories burned per day; a peak of 1,000 watts output at any given moment (enough juice to run seven iMacs). The two most important figures: 6, the number of consecutive victories Armstrong will have if he wins the Tour again (a new record); and 61, the number of seconds he won by last year, his narrowest margin yet.

To ensure the 32-year-old Texan has every advantage, his equipment sponsors have joined forces in an unprecedented, cost-be-damned collaboration known as F-One. Their goal: to get Armstrong's rig as close as possible to the Union Cycliste Internationale minimum bike weight of 6.8 kilograms (about 15 pounds) and make the rest of his gear as light and aerodynamic as possible. After all, even the slightest improvements can pay off. In 1989, Greg LeMond won the Tour by eight seconds - a victory universally attributed to the aerodynamic handlebars he used in the final time trial. While some of Armstrong's custom-made equipment won't be ready until race day, other items are premium versions of gear for sale at your local cycling shop. Here's a glimpse at the hardware designed to keep Armstrong in the yellow jersey.

HELMET: Giro Atmos, $190 The 9.53-ounce Atmos sports a carbon fiber subframe - a first for cycling helmets. This roll-cage subtracts 0.7 ounces from Giro's previous top skid lid without sacrificing protection.

JERSEY: Nike HC, custom Nike's Dri-FIT fabrics, along with a no-sew seaming technique, helped create a 4-ounce top that's 30 percent lighter than last year's winning jersey (shown here - the new model's still in stealth mode). To reduce drag, the back is covered with mesh four times lighter than the main body fabric. A chest vent sucks in air when upright and closes when hunched.

SHOES: Nike Lance, $300 The Swoosh folks blew through 100 prototypes before settling on this 11.29-ounce design. Seven-layer soles provide optimum power transfer, an aluminum ratcheting buckle ensures a precise fit, and water- and stretch-resistant synthetic leather protects during heat and frequent downpours.

FRAME: Trek Madone 5.9, $2,800 By building with carbon fiber instead of aluminum, Trek significantly improved its biking aerodynamics: Wind-tunnel testing shows that this 2.43-pound frame reduces the leg power required to maintain a given speed by 10 watts. And by varying the density and direction of individual fibers, Trek made a bike that's both vertically pliable for comfort and laterally rigid for efficiency during hard pedaling. Armstrong is also testing a variation called the Madone SL, which sheds a few more ounces by shaving excess material from the seat tube.

WHEELS: Bontrager Race XXX Lite, custom Wheels are among the trickiest components in cycling: Rotating weight has a greater impact than static weight because a rider must move it with every revolution. This year, Bontrager used carbon fiber in the hub, which, in addition to the carbon fiber rims introduced last year, keeps the weight of both wheels to 42.32 ounces. The company has also developed a special set of wheels for the Tour's new time trial up l'Alpe d'Huez. Made from expensive aerospace-grade carbon fiber, these hoops were built to be as light as possible for climbing, trimming another 3.5 ounces from each wheel. The trade-off is that safety functions like durability and braking have been sacrificed. After scaling the mountain, the wheels will be tossed.

By Matt Burgess

By Sachi Mulkey

By Andy Greenberg

By Matthew Gault

COMPONENT SET: Shimano Dura-Ace, $1,350 On long climbs, Armstrong pedals a hummingbird-like 100 to 110 rpm while his rivals tend to slow to about 70 rpm. This quick cadence lets Armstrong play to his cardiovascular strength rather than rely on muscle power. To help him, Shimano added a 20th gear to his drivetrain and shaved 4.48 ounces from the entire component group by using hollow forged-aluminum crank arms and titanium (not steel) rear gear cogs.

TWO-WAY RADIO: Alinco DJ-C5T, $199 Riders and coaches used to talk via bullhorn; now it's two-way radio. This credit card-sized 2.99-ounce unit lets Armstrong & Co. strategize in secret.

FUEL: PowerBar, $1.79 To help replace the 110,000 calories (31 pounds!) Armstrong will burn during the race, he will nosh on some 105 PowerBars and 210 PowerGels. Yum.

WATER BOTTLE CAGE: Trek Bat, $7 At 1.55 ounces, this cage isn't that light. And it's not made of space-age materials (nylon composite is a geek term for plastic). So what gives? It's only $7, which means you can buy it for less than the price of Armstrong's 2001 best seller (now in paperback).

PEDALS: Shimano Dura-Ace, $215 Armstrong used a pair of decade-old pedals because he liked the way they felt. Last year, Shimano delivered a model with a broader platform, and Armstrong cut 7.06 ounces from every crank rotation.

COMPUTER: Ciclosport HAC 4 Plus, $440 In training, Armstrong relies on a heavy and expensive power meter that measures output via specially designed crank arms. For the big race, Armstrong slims down to this standard - albeit top of the line - cycling computer to track speed, heart rate, incline, cadence, altitude gain, and power output.

Scott Gilbertson

Christopher Null

Nena Farrell

Nicole Kinning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Generative AI

- Business Operations

- Cloud Computing

- Data Center

- Data Management

- Emerging Technology

- Enterprise Applications

- IT Leadership

- Digital Transformation

- IT Strategy

- IT Management

- Diversity and Inclusion

- IT Operations

- Project Management

- Software Development

- Vendors and Providers

- Enterprise Buyer’s Guides

- United States

- Middle East

- España (Spain)

- Italia (Italy)

- Netherlands

- United Kingdom

- New Zealand

- Data Analytics & AI

- Newsletters

- Foundry Careers

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Copyright Notice

- Member Preferences

- About AdChoices

- Your California Privacy Rights

Our Network

- Computerworld

- Network World

Lance Armstrong: Cycling Power

Lance Armstrong doesn’t track his speed when he trains for next month’s Tour de France. The number he craves is measured in watts, not miles per hour. Power output dominates the training of top cyclists like Armstrong because it’s a much more accurate gauge of performance than speed (at the mercy of the wind) or even heart rate (too fickle), say experts.

Power never lies because it is a direct measure of the force applied to the bike (torque) that is converted into a measure of power output (watts). By measuring how many watts he expends on a mountain climb, Armstrong can develop a training program that duplicates those race efforts down to the watt. For the past seven years, Armstrong has used a $2,600 device called the SRM Powermeter, developed by German medical engineer Ulrich Schoberer in the late 1980s. The Powermeter measures deflection of the pedal crankarm using tiny strain gauges and converts the measures into watts on a handlebar computer that can store and download 70 hours worth of wattage (and heart rate) for analysis?numbers that Armstrong pores over obsessively.

Armstrong sure can crank. During the final hour of a seven-hour stage of the Tour, he can pedal at an average of 400 watts. (Track racers have pushed it over 2,000 watts for a few seconds. The average cyclist can barely light a 100-watt lamp.) “Pro cyclists used to train according to how they felt,” says David Cathcart, marketing director for CycleOps Performance Training Products, which makes a watt measurement device called Powertap. “Now it’s all about metrics.”

Related content

The hp-autonomy lawsuit: timeline of an m&a disaster, jury clears autonomy ceo of fraud charges, aes enlists ai to boost its sustainable energy business, top 8 it certifications in demand today, from our editors straight to your inbox, show me more, the raci matrix: your blueprint for project success.

The AI revolution is here. How do you make sense of it?

Salesforce updates Sales and Service Cloud with new capabilities

CIO Leadership Live NZ with Lena Jenkins, Chief Digital Officer, Waste Management NZ

Northwestern Mutual’s CIO Jeff Sippel on productivity gains with AI

Rimini Street’s Eric Helmer and the top questions to ask about vendor support

UAE CISOs: Key priorities unveiled

Sponsored Links

- Everybody's ready for AI except your data. Unlock the power of AI with Informatica

- The cloud shouldn’t be complicated. Unlock its potential with SAS.

- Everyone’s moving to the cloud. Are they realizing expected value?

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Science Behind Armstrong's Alpine Success

Tom Goldman

The Tour de France resumes Tuesday and heads into the French Alps, where cyclist Lance Armstrong attempt his seventh consecutive win. A researcher in Texas reveals some of the science behind Armstrong's success.

Copyright © 2005 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The making of Mr Invincible

Soon after breakfast this morning, 161 of the world's top cyclists will mount their machines at Lezat-sur-Leze in the Pyrenees and embark on one of the toughest stages of the world's most gruelling sporting challenge, the Tour de France . They will spend the best part of seven hours in the saddle and, in draining heat, tackle 205.5km (128 miles) of hills, passes and climbs of unremitting cruelty at speeds which average 28-30mph but sometimes reach 65mph. No wonder the riders describe the Tour as three weeks of torture.

Whatever their best efforts, by tonight one man - Lance Armstrong - will almost certainly still be in the lead. Cycling's icon and figurehead is chasing an astonishing seventh consecutive win in an event which requires superhuman qualities. His tactics are simple: 'It's attack until they crack, or I do,' he says.

If he triumphs yet again when the Tour ends on the Champs-Elysees next Sunday, the American will have both rewritten the annals of sporting achievement and redefined the limits of human endeavour. Unhappily for his rivals, the 33-year-old Texan has more heart than them for the task ahead - quite literally.

'Genetically Lance is a freak,' says his friend Tony Doyle, the British former pursuit cycling world champion. 'His heart and lungs are bigger than most people's, and most other elite cyclists', so they make him more efficient as an athlete. He also generates far less lactic acid than the others, and he recovers quicker - vital in a race where you push yourself to the limit day after day after day.'

Most usefully, though, Armstrong is a survivor. 'Although the Tour is excruciatingly painful, for Lance it is still not as tough a battle as when he overcame testicular cancer,' explains Doyle. 'That means that he is mentally strong, very driven and has a lot higher pain threshold than the other guys because he's beaten a life-threatening disease. He can suffer that bit more.'

Cancer gave Armstrong the worst times of his life. Hearing he had a 60 per chance of dying. Having surgery to remove one testis. Chemotherapy to fight tumours that had spread to his lungs and brain. Five months in hospital as he defied doctors' expectations. But illness was also the making of him.

'In a strange way cancer did him a huge favour,' says Daniel Coyle, author of the recent biography Lance Armstrong: Tour de Force . 'It removed 15lbs of muscle and resculpted his body into the leaner shape. Before then he had been too big and too muscular, especially in the upper body. And it gave him the discipline that, allied to his talent, turned him into the sporting phenomenon he is today.

'He was already a world champion, but he had been an undisciplined kid: brash and uncontrollable. After he was diagnosed with cancer, he began displaying discipline at the millimetre level.'

When the doctor told him his body was riddled with tumours, Armstrong took in the news for a couple of minutes and then said: 'Let's get started. Let's kill this stuff.' Coyle says: 'He adopted a very scientific approach to fighting the cancer.' Out went coffee, red meat and dairy products. 'He went after the cancer in a very organised, methodical, aggressive way, and came away with an appreciation of what discipline could do for him.

He approaches cycling the same way. He weighs his food to ensure he does not go above his optimum weight, and constantly monitors his bodyfat ratio. 'After cancer, he turned the Tour into a problem he wanted to solve,' says Coyle.

'He pays attention to every last detail that contributes to the pursuit of excellence. That's what sets him apart,' believes Dave Brailsford, the performance director at British Cycling . 'He is always looking to make a tiny improvement to his nutrition, his position on the bike, or the science of how he trains.'

Thus he avoids ice cream, in case it causes indigestion, or carbonated water, lest it induce diarrhoea, or chocolate mousse - excessive sweating - and does not shave his legs the night before racing, in case the minimal energy required to regrow the hair makes a difference.

He has two key numbers: 74, his optimal weight in kilos, and 500, which is his maximum sustainable power in watts. If they are both right he will produce 6.7 watts per kilo. If he does that, he will almost certainly win. His key advantage is that he can sustain that power for an hour at a time, even up and down the Pyrenees. Germany's Jan Ullrich, his nearest rival, cannot quite match Armstrong's consistency.

'He is not happy until he has found "the shit" - the coolest helmet, or fastest bike or best teammate. He's about trying to make himself into "the shit", the thing nobody has seen before', says Coyle. His eight teammates in the Discovery Channel team, and their 30-strong back-up squad of specialists, all share one goal: for Armstrong to win.

His feats have inevitably prompted speculation thathis success might be down to performance-enhancing substances. Allegations to that effect in a book last year have led to ongoing legal action. Armstrong denies the accusations and has always tested negative.

Any conversation with one of cycling's cognoscenti about what makes Armstrong so good comes back to his cancer and the tough childhood which forged his iron will. He was born Lance Gunderson in Plano, Texas, in September 1971, when his mother, Linda Mooneyham, was 17. Her marriage to his father, Eddie Gunderson, broke down when he was just three. Armstrong has never spoken to, or about, his father since. 'Lance would undoubtedly not have turned out the way he has _ if I had stayed with his mother,' Gunderson admitted recently. 'I would probably have ballsed the whole thing up.'

Armstrong was named after Lance Retzel of the Dallas Cowboys gridiron team; his surname came from his mother's second husband, Terry Armstrong, his ex-stepfather. Times were hard for mother and son, financially and emotionally. 'When things got tough, I would always tell Lance that "this isn't a problem, this is an opportunity",' she has said. 'We weren't afraid of failing, only of giving up. Losing is worthwhile if you learn something worthwhile from it.'

But losing is the last thing on Armstrong's mind. Next Sunday, come what may, he intends to retire - and wants to bow out on a high, as a champion and a history-maker.

His place in posterity assured, he plans to unwind, spend more time with the three children from his first marriage, start a new family with his girlfriend, the rock singer Sheryl Crow, and devote even more energy to his cancer charity.

An adviser to George W Bush on the President's Cancer Panel, there is even talk of a career in politics, and following in Bush's steps by running for governor of his home state. Before then, though, there is one last week in the saddle - one final battle for the ultimate winner.

The Tour in figures

The Tour de France began in 1903 but was almost abandoned in 1904 because cheating was so common

There are 21 stages in 23 days over a total of 2,241 miles. The longest is 239.5km (150 miles)

Riders reach up to 70mph. At such speeds a burst tyre, skid or collision can be fatal

It is very demanding: 28 riders have dropped out already this year. Belgium's Georges Goffin began the race in 1909, 1911 and 1922 but never lasted beyond day one

The Alpe d'Huez has 21 'switchbacks', turns of at least 90 degrees

Riders often relieve themselves in the saddle to save time

Competitors consume up to 7,500 calories a day

Top riders earn about £1m a year, though Armstrong makes around £10m in race fees, prize money and sponsorship

Britain's Bradley Wiggins won a gold, silver and bronze at the 2004 Olympics but there are no Britons in the Tour de France

- Tour de France 2005

- The Observer

- Tour de France

- Lance Armstrong

Most viewed

In a spin: what all cyclists should know about pedalling cadence

Cadence and efficiency

Box 1: the power of indurain.

Power, force and cadence

Figure 1: relationship between peak torque, peak power and pedalling cadence (3).

Table 1: Difference between 80rpm and 100rpm during prolonged sub-maximal cycling

Figure 2: Effects of cycling cadence on maximal power during exercise to exhaustion

Freedom of choice

Cadence and hills.

- *The relationship between cadence and gross efficiency appears to be unchanged when cycling uphill – ie, lower cadences are likely to be more efficient and thus save energy in the longer run;

- *Despite this, the greater forces needed to cycle uphill means that while a lower cadence may be more energetically efficient, it might result in more lactate accumulation. Given that (on longer climbs), a significant accumulation of lactate will slow the cyclist significantly and may even force him/her to stop, losing a little efficiency by using a higher cadence (which reduces the forces on muscle fibres) is a price worth paying;

- *The cyclist’s body position during seated climbing doesn’t appear to affect efficiency but a more upright stance might help lower lactate accumulation.

Figure 3: Gross efficiency, incline and seat position (13)

Training your GE

- An intervention group who performed half-squats, four sets of 4 repetitions maximum, 3 times per week for eight weeks, as a supplement to their normal endurance training.

- A control group who continued their normal cycling training during the same period with no strength training.

Summary and conclusions

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012 Dec;7(4):397-400

- J. Appl. Physiol 2005; 98:2191-2196

- Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32(7): 1281-1287

- Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (2014) 13, 114-119

- Acta Physiologica Scandinavia 2002; 176(3), 185-194

- J Appl Physiology 1975; 38(6), 1132-1139

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2009 Mar;4(1):3-17

- Experimental Brain Research 2008; 186 (3),365-373.

- Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2012 Mar;5(1):44-66

- Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012 Dec;7(4):375-81

- Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012 Jul;112(7):2433-41

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013 May;45(5):920-6

- Eur J Appl Physiol (2011) 111:2885–2893

- J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Nov;19(4):826-30

- J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Aug;24(8):2157-65

- Int J Sports Med. 2009 Jan;30(1):27-32

- Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011 Apr;21(2):250-9

Andrew Hamilton

Andrew Hamilton BSc Hons, MRSC, ACSM, is the editor of Sports Performance Bulletin and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine. Andy is a sports science writer and researcher, specializing in sports nutrition and has worked in the field of fitness and sports performance for over 30 years, helping athletes to reach their true potential. He is also a contributor to our sister publication, Sports Injury Bulletin.

Register now to get a free Issue

Latest Issue

- What really works for distance runners?

- The truth about athletic retirement

- Mental fatigue for physical performance

- Optimum BCAA intake for recovery

- Fitness testing for swimmers made simple

Subscribe Today

- Unlimited Access

- Monthly Magazine

- Back Issue Library

- Email Newsletter

Quantifying intensity, practical guide on how to identify your own dominant side and bring the other side up to par, vo2max is a poor predictor of performance, but computing your velocity at vo2max can pay big benefits, swimming performance: is bilateral breathing a must, the drop depth jump: a plyometric exercise to increase vertical leap and improve jumping ability, newsletter sign up, testimonials, dr. alexandra fandetti-robin, back & body chiropractic, elspeth cowell msch dpodm srch hcpc reg, william hunter, nuffield health, further reading, can your pedalling technique make you a more efficient rider, cycling training: how reducing your drag will improve your cycling performance, cyclists: position yourself for performance, efficiency matters, editor's picks, endurance and strength: you have the best of both worlds, training intensity: is higher better, even for beginners, endurance performance: can a short, sharp shock work wonders, high-intensity training: are sprint intervals overhyped, mass with class: why sleep matters, further reading.

Swimming fitness: the truth about testing and monitoring

BFR: easy does it for improved endurance

Tuning your training: should you factor in body type?

The perfect training plan: human vs. artificial intelligence

Coaches Testimonials

- Weekly Magazine

- Online Library

- Elbow and Arm Injuries

- Diagnosis and Treatment

Keep up with latest sports science research and apply it to maximize performance

Today you have the chance to join a group of athletes, and sports coaches/trainers who all have something special in common...

They use the latest research to improve performance for themselves and their clients - both athletes and sports teams - with help from global specialists in the fields of sports science, sports medicine and sports psychology.

They do this by reading Sports Performance Bulletin, an easy-to-digest but serious-minded journal dedicated to high performance sports. SPB offers a wealth of information and insight into the latest research, in an easily-accessible and understood format, along with a wealth of practical recommendations.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Performance Bulletin helps dedicated endurance athletes improve their performance. Sense-checking the latest sports science research, and sourcing evidence and case studies to support findings, Sports Performance Bulletin turns proven insights into easily digestible practical advice. Supporting athletes, coaches and professionals who wish to ensure their guidance and programmes are kept right up to date and based on credible science.

More from us

© 2023 sports performance bulletin, part of green star media ltd. company number: 3008779.

Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn?

Professor of Physics, University of Lynchburg

Disclosure statement

John Eric Goff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Imagine you begin pedaling from the start of Stage 17 of this year’s Tour de France . First, you would bike approximately 70 miles (112 km) with a gradual increase in elevation of around 1,300 feet (400 m). But you’ve yet to hit the fun part: the Hautes-Pyrénées mountains. Over the next 40 miles (64 km) you would have to climb three mountain peaks with a net increase of a mile (1.6 km) in elevation . On the fittest day of my life, I might not even be able to finish Stage 17 – much less do it in anything remotely close to the five hours or so the winner will take to finish the ride. And Stage 17 is just one of 21 stages that must be completed in the 23 days of the tour.

I am a sports physicist , and I’ve modeled the Tour de France for nearly two decades using terrain data – like what I described for Stage 17 – and the laws of physics. But I still cannot fathom the physical capabilities needed to complete the world’s most famous bike race. Only an elite few humans are capable of completing a Tour de France stage in a time that’s measured in hours instead of days. The reason they’re able to do what the rest of us can only dream of is that these athletes can produce enormous amounts of power. Power is the rate at which cyclists burn energy and the energy they burn comes from the food they eat. And over the course of the Tour de France, the winning cyclist will burn the equivalent of roughly 210 Big Macs.

Cycling is a game of watts

To make a bicycle move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bicycle and to the wheels that push back on the ground. The faster a rider can put out energy, the greater the power. This rate of energy transfer is often measured in watts. Tour de France cyclists are capable of generating enormous amounts of power for incredibly long periods of time compared to most people.

For about 20 minutes, a fit recreational cyclist can consistently put out 250 watts to 300 watts . Tour de France cyclists can produce over 400 watts for the same time period . These pros are even capable of hitting 1,000 watts for short bursts of time on a steep uphill – roughly enough power to run a microwave oven .

But not all of the energy a Tour de France cyclist puts into his bike gets turned into forward motion. Cyclists battle air resistance and frictional losses between their wheels and the road. They get help from gravity on downhills but they have to fight gravity while climbing.

I incorporate all of the physics associated with cyclist power output as well as the effects of gravity, air resistance and friction into my model . Using all that, I estimate that a typical Tour de France winner needs to put out an average of about 325 watts over the roughly 80 hours of the race. Recall that most recreational cyclists would be happy if they could produce 300 watts for just 20 minutes!

Turning food into miles

So where do these cyclists get all this energy from? Food, of course!

But your muscles, like any machine, can’t convert 100% of food energy directly into energy output – muscles can be anywhere between 2% efficient when used for activities like swimming and 40% efficient in the heart . In my model, I use an average efficiency of 20%. Knowing this efficiency as well as the energy output needed to win the Tour de France, I can then estimate how much food the winning cyclist needs.

Top Tour de France cyclists who complete all 21 stages burn about 120,000 calories during the race – or an average of nearly 6,000 calories per stage. On some of the more difficult mountain stages – like this year’s Stage 17 – racers will burn close to 8,000 calories. To make up for these huge energy losses, riders eat delectable treats such as jam rolls, energy bars and mouthwatering “jels” so they don’t waste energy chewing .

Last year’s winner , Tadej Pogačar, weighs only 146 pounds. Tour de France cyclists don’t have much fat to burn for energy. They have to keep putting food energy into their bodies so they can put out energy at what seems like a superhuman rate. So this year, while watching a stage of the Tour de France, note how many times the cyclists eat – now you know the reason for all that snacking.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter .]

- Tour de France

- Bicycle racing

- Pyrenees mountains

- Significant Figures

- Sports medicine

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

- Topics ›

- Cycling ›

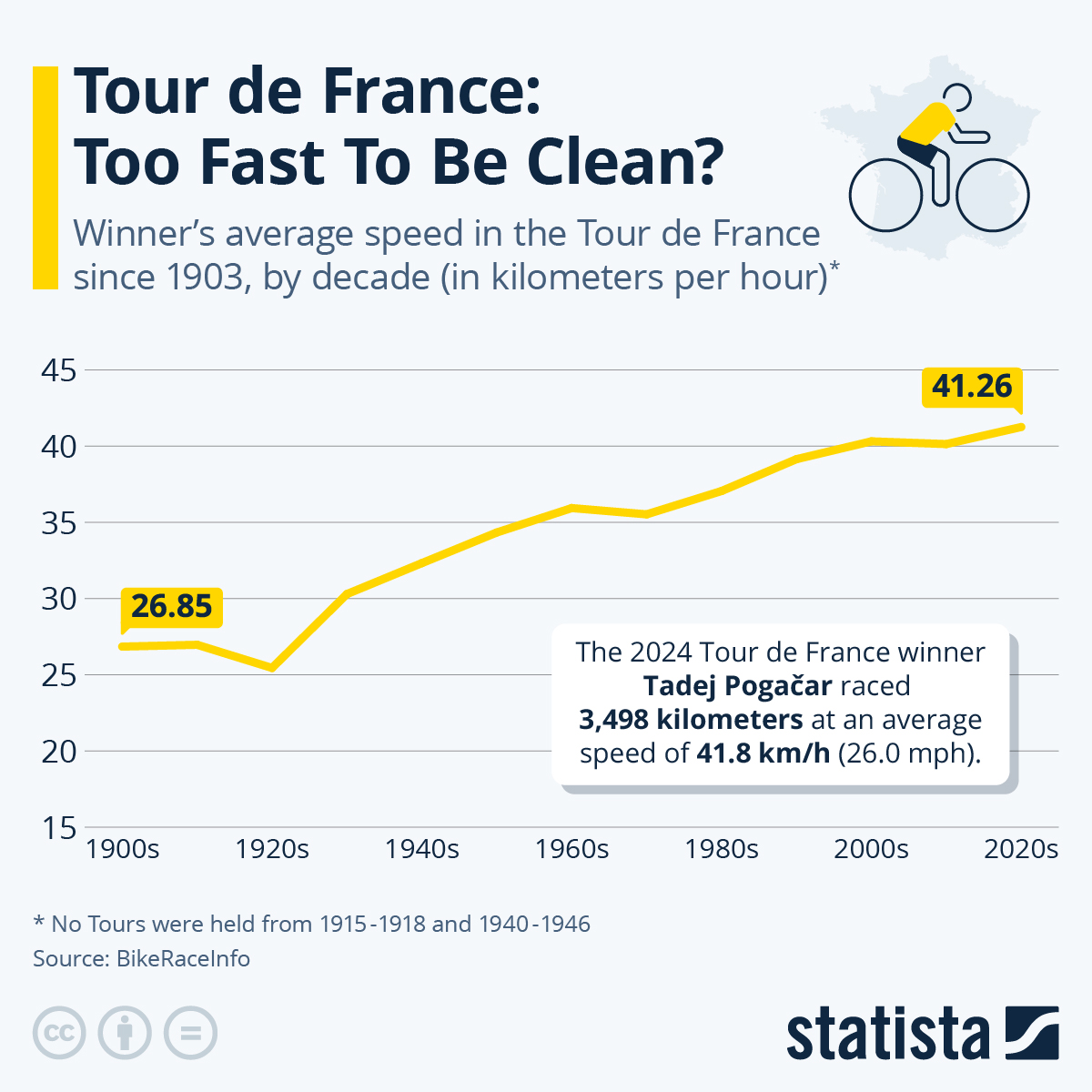

Tour de France: Too Fast To Be Clean?

Tour de france.

Denmark's Jonas Vingegaard claimed his second Tour de France victory on Sunday, completing the grueling 3-week, 3,401 kilometer competition with an average speed of 41.12 km/h (25.55 mph). Even before officially getting his hands on the famous maillot jaune mascot though, Vingegaard was facing tough questions regarding his pace. How was he going so fast? How was it possible to be over seven minutes ahead of a cyclist of Pogačar's caliber? Some reporters even explicitly asking: "Are you cheating?".

Vingegaard's response? In a post-stage 17 press conference, the Dane proclaimed: "For me, it’s hard to tell what more you can say. I guess, I understand that it’s hard to trust in cycling with the past there has been. But I think nowadays everyone is different than they were 20 years ago. And I can tell from my heart that I don’t take anything. I don’t take anything I would not give to my daughter, and I would definitely not give her any drugs.”

Assuming he is indeed clean, it is unfortunate for this year's victor that it has become the norm, given cycling's deservedly bad reputation, for exceptional performances to raise suspicions. As this chart shows, the Tour de France has not slowed down since the doping-infested years of the early 2000s. Whether that's due to super-fast carbon bikes, favorable routing or the use of performance-enhancing substances is a question the sport is not yet fully able to answer.

Description

This chart shows the average speed of Tour de France winners since 1903, by decade (in kilometers per hour).

Can I integrate infographics into my blog or website?

Yes, Statista allows the easy integration of many infographics on other websites. Simply copy the HTML code that is shown for the relevant statistic in order to integrate it. Our standard is 660 pixels, but you can customize how the statistic is displayed to suit your site by setting the width and the display size. Please note that the code must be integrated into the HTML code (not only the text) for WordPress pages and other CMS sites.

Infographic Newsletter

Statista offers daily infographics about trending topics, covering: Economy & Finance , Politics & Society , Tech & Media , Health & Environment , Consumer , Sports and many more.

Related Infographics

The countries dominating the tour de france, has pro cycling cleaned up its act, where cycling has an uphill battle for fans, americans lose interest in post-armstrong tour de france, fortnite world champion bags $3 million prize, tour de france: the 20-year fight against doping, how esport prize purses compare to traditional sports, can the tour de france shake its tarnished past.

- Who may use the "Chart of the Day"? The Statista "Chart of the Day", made available under the Creative Commons License CC BY-ND 3.0, may be used and displayed without charge by all commercial and non-commercial websites. Use is, however, only permitted with proper attribution to Statista. When publishing one of these graphics, please include a backlink to the respective infographic URL. More Information

- Which topics are covered by the "Chart of the Day"? The Statista "Chart of the Day" currently focuses on two sectors: "Media and Technology", updated daily and featuring the latest statistics from the media, internet, telecommunications and consumer electronics industries; and "Economy and Society", which current data from the United States and around the world relating to economic and political issues as well as sports and entertainment.

- Does Statista also create infographics in a customized design? For individual content and infographics in your Corporate Design, please visit our agency website www.statista.design

Any more questions?

Get in touch with us quickly and easily. we are happy to help.

Feel free to contact us anytime using our contact form or visit our FAQ page .

Statista Content & Design

Need infographics, animated videos, presentations, data research or social media charts?

More Information

The Statista Infographic Newsletter

Receive a new up-to-date issue every day for free.

- Our infographics team prepares current information in a clear and understandable format

- Relevant facts covering media, economy, e-commerce, and FMCG topics

- Use our newsletter overview to manage the topics that you have subscribed to

The average speed reached by the winners of the Tour de France increased by 53.9% since the first race in 1903 through 2016. This means an average speed increase rate of 0.42% each Tour.

The upward trend reached its peak at 41.65 km/h with the 7th consecutive win by the US cyclist Lance Armstrong in 2005. Average speeds fell since then until 2010, in spite of the participation of the same fast riders, which suggests more stringent anti-doping regulations and controls (see areppim's insight ). Since 2010, the average speed of the Tour winner resumed its ascending trend, approaching the long-term linear trend (red line in the chart), before slowing down a bit in 2015 and especially in 2016.

One cannot avoid suspecting the doings of illegal sports medical practices to be responsible for such high level performances. Indeed, the 2015 Tour had one rider excluded for positive control on drugs, and hot controversy surrounded the Tour winner's allegedly extraordinary performance. The doping affairs that tarnished the Tour champions' reputations since 1996 cast a dubious halo on the popular sports event. But, for that matter, other sports are not immune: tennis, soccer, running, practically all sport disciplines have been subject to on-going controversy after whistle blowers alerted to a variety of doping practices.

Sources: Le Tour de France

SUMMER GETAWAY IDEAS?

New! Find answers in a flash with Scout, our friendly AI chat otter.

TRY IT OUT →

BEST WEEK EVER

Try out unlimited access with 7 days of Outside+ for free.

Start Your Free Trial

Armstrong Wins Sixth Tour de France

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

U.S. Postal’s Lance Armstrong won an unprecedented sixth consecutive Tour de France Sunday, besting his closest competitor by over six minutes in the overall standings. “Everything went perfectly,” the Texan said in French on the three-step victory podium. “The tactics, the training, everything. The team was the best one here.”

Lance Armstrong wins a history-making sixth Tour de France victory

Asked if he would be back next year, Armstrong replied, “I can’t see myself not being in the Tour.” Pressed then to say that he would defend his championship, he answered only, “We’ll see.” Armstrong owed his overwhelming success in this year’s Tour to obsessive training and preparation, and to his top-notch team of professional cyclists. U.S. Postal’s director, Johann Bruyneel, offered high praise to the men who supported their team leader throughout the race by riding in formation to protect Armstrong from crashes and help him to conserve energy for important attacks. “It’s a team that exists only for the Tour,” Bruyneel told The New York Times . “Everything that they do beforehand serves only to prepare for this objective. They’re all fine riders with lots of experience.” Armstrong was content to finish at the back of the peloton Sunday, enjoying his sixth Tour win and staying out of the sprinters’ way at the front of the race. After all, there was no threat to the Texan’s overall standing. Whereas Armstrong won last year’s race by a mere 61 seconds, this year he bested closest competitor Andréas Klön (T-Mobile) by 6:19 and posted a total of five Tour stage wins—the most ever for the U.S. Postal leader. Tom Boonen (Quick Step-Davitamon) won the final stage of the Tour in a rush for the finish line on the 102-mile course from Montereau to Paris, which included eight laps around the Champs-Élysées in the city’s downtown. Italian rider Ivan Basso (CSC) placed third 6:40 behind Armstrong and in front of long-time Armstrong rival Jan Ullrich (T-Mobile). Ullrich’s fourth place finish 8:50 behind the Texan was a career worst for the German. Armstrong teammate and U.S. Postal domestique José Azevedo finished fifth overall. In the other classifications, Australian rider Robbie McEwen (Lotto-Domo) clinched his second career green jersey in the sprinter classification and Frenchman Richard Virenque (Quick Step-Davitamon) won an unprecedented seventh polka dotted jersey in the climbing, or King of the Mountain, classification. Russian rider Vladimir Karpets (Illes Balears-Banesto) took the white jersey for the best young rider after wresting it from French National Champion Thomas Voeckler (Brioches La Boulangere). Voeckler, who had worn the yellow jersey for more days than any other Frenchman in over a decade, lost the jersey to Karpets after Stage 19’s individual time trial Saturday. T-Mobile placed first in the overall team standings with U.S. Postal on its heels in second and CSC in third. Sunday’s stage proved to play out as expected with the sprinters having their last chance to shine on the final stage of the Tour and much of the rest of the peloton taking the stage relatively easy. A break by Nicolas Jalabert (Phonak), Oscar Pereiro Sio (Phonak), Juan Antonio Flecha (Fassa Bortolo), José Ivan Gutierrez (Illes Balears-Banesto), Paolo Bettini (Quick Step- Davitamon), Thomas Voeckler (Brioches La Boulangere), Scott Sunderland (Alessio Bianchi), Mikel Astarloza (Ag2r), Karsten Kroon (Rabobank), and Axel Merckx (Lotto-Domo) garnered the group a lead of about 40 seconds but, with under six miles remaining in the Tour, the group was chased down, with Ullrich leading the catch. Attacks by Jalabert, Flecha, and Fabian Cancellara (Fassa Bortolo) ultimately failed in the final laps. The sprinters gave it their all to cross the finish line, and Boonen was able to grab his second stage win of the Tour. Nazon finished second on the day while Danilo Hondo (Gerolsteiner), McEwen, and Erik Zabel (T-Mobile) rounded out the top five. With Armstrong opting out of the Olympics (and American Levi Leipheimer (Rabobank), who finished ninth in this year’s Tour, replacing him), Discovery Channel taking over U.S. Postal’s sponsorship, and much of Armstrong’s team slated to return, the only question remaining is whether the Texan will attempt to score a seventh win in 2005.

Popular on Outside Online

Enjoy coverage of racing, history, food, culture, travel, and tech with access to unlimited digital content from Outside Network's iconic brands.

Healthy Living

- Clean Eating

- Vegetarian Times

- Yoga Journal

- Fly Fishing Film Tour

- National Park Trips

- Warren Miller

- Fastest Known Time

- Trail Runner

- Women's Running

- Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- FinisherPix

- Outside Events Cycling Series

- Outside Shop

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

Calculators

Running events, running articles, triathlon events, cycling events, triathlon articles, cycling articles, fitness events, fitness articles, sports events, outdoor events, sports articles, nutrition articles, health & injury articles, lance armstrong: how does he do it.

Armstrong, a six-time winner of the Tour de France bicycle race who next month will try for his seventh straight victory, can cover 32 miles, or 50 kilometers, in one hour of riding. In contrast, the average cyclist covers 16 miles; a top marathon runner can cover 21 miles on a bike.

Armstrong can ride up the mountains in France generating about 500 watts of power for 20 minutes, something a typical 25-year-old could do for only 30 seconds. A professional hockey player might last three minutes and then throw up.

How does he do it?

So how does he do it? According to a scientist who studied Armstrong at regular intervals from 1992 to 1999, his prowess can be explained by a set of physiological changes that took place in his body over those seven years and that, in all probability, are continuing.

The changes are described in an article entitled "Improved Muscular Efficiency Displayed as Tour de France Champion Matures" in the June issue of The Journal of Applied Physiology .

The scientist, Edward Coyle, director of the Human Performance Laboratory at the University of Texas, has studied cyclists for 25 years. He says they need large hearts and low levels of lactic acid the byproduct of intense exercise in their blood. Their efficiency, measured as how many watts of cycling power are generated for a given cycling input, needs to be high.

"Lance came to us when he was 20 years old, very early in his career," Coyle said. "He wanted to know what he could do to improve himself."

Armstrong, Coyle said, indeed had an exceptionally large heart and low lactic acid. "But his muscle efficiency was not very good," he said. "It came in at 21 percent. That first year two other athletes we studied were better."

Armstrong showed subsequent improvements until his career was stopped short in 1996 with a diagnosis of testicular cancer. Eight months after his treatment ended, he was back in the Austin, Texas, laboratory.

"He wanted to know if anything was permanently wrong," Coyle said.

They took measurements and found nothing to stop him, except his own willingness to compete.

Armstrong did compete.

Improved efficiency: Increased slow-twitch muscles

"In the next two years his heart got even better, his lactic acid dropped further and, amazingly, his efficiency increased to 23 percent," Coyle said.

That may not sound like much, but it means that for the same level of oxygen consumption, Armstrong gets more power to the pedals. By taking off body weight, he was delivering 18 percent more power to his muscles.

There is only one way such efficiency could improve, Coyle said: more slow-twitch muscles, the type that do not burn out quickly and that are used in standing or walking. Fast-twitch muscles, which burn out fast, are used for sprinting and heavy lifting.

Rodent studies show that chronic stimulation to muscle tissue increases the amount of slow-twitch fibers, Coyle said. Armstrong appears to have increased the proportion of his slow-twitch muscles from 60 percent to 80 percent.

In bicycle races, slow-twitch fibers are up to twice as efficient as fast twitch.

In the long line of Tour de France cheats, Lance Armstrong stands out.

Opinion: Lance One of Many Tour de France Cheaters

Armstrong took a long history of Tour de France cheating to a new level, the author argues.

Editor's note: England-based writer and photographer Roff Smith rides around 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers) a year through the lanes of Sussex and Kent and writes cycling blog My Bicycle and I.

And so, the television correspondent said to the former Tour de France champion, a man who had been lionised for years, feted as the greatest cyclist of his day, did you ever use drugs in the course of your career?

"Yes," came the reply. "Whenever it was necessary."

"And how often was that?" came the follow-up question.

"Almost all the time!"

This is not a leak of a transcript from Oprah Winfrey's much anticipated tell-all with disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong, but instead was lifted from a decades-old interview with

Fausto Coppi

, the great Italian road cycling champion of the 1940s and 1950s.

To this day, though, Coppi is lauded as one of the gods of cycling, an icon of a distant and mythical golden age in the sport.

So is five-time Tour winner

Jacques Anquetil

(1957, 1961-64) who famously remarked that it was impossible "to ride the Tour on mineral water."

"You would have to be an imbecile or a crook to imagine that a professional cyclist who races for 235 days a year can hold the pace without stimulants," Anquetil said.

And then there's British cycling champion

Tommy Simpson

, who died of heart failure while trying to race up

Mont Ventoux

during the 1967 Tour de France, a victim of heat, stress, and a heady cocktail of amphetamines.

All are heroes today. If their performance-enhancing peccadillos are not forgotten, they have at least been glossed over in the popular imagination.

As the latest chapter of the sorry Armstrong saga unfolds, it is worth looking at the history of cheating in the Tour de France to get a sense of perspective. This is not an attempt at rationalization or justification for what Armstrong did. Far from it.

But the simple, unpalatable fact is that cheating, drugs, and dirty tricks have been part and parcel of the Tour de France nearly from its inception in 1903.

Cheating was so rife in the 1904 event that Henri Desgrange, the founder and organizer of the Tour, declared he would never run the race again. Not only was the overall winner,

Maurice Garin

, disqualified for taking the train over significant stretches of the course, but so were the next three cyclists who placed, along with the winner of every single stage of the course.

Of the 27 cyclists who actually finished the 1904 race, 12 were disqualified and given bans ranging from one year to life. The race's eventual official winner, 19-year-old

Henri Cornet

, was not determined until four months after the event.

And so it went. Desgrange relented on his threat to scrub the Tour de France, and the great race survived and prospered—as did the antics. Trains were hopped, taxis taken, nails scattered along the roads, partisan supporters enlisted to beat up rivals on late-night lonely stretches of the course, signposts tampered with, bicycles sabotaged, itching powder sprinkled in competitors' jerseys and shorts, food doctored, and inkwells smashed so riders yet to arrive couldn't sign the control documents to prove they'd taken the correct route.

And then of course there were the stimulants: brandy, strychnine, ether, whatever—anything to get a rider through the nightmarishly tough days and nights of racing along stages that were often over 200 miles (320 kilometers) long. In a way the race was tailor-made to encourage this sort of thing. Desgrange once famously said that his idea of a perfect Tour de France would be one that was so tough that only one rider finished.

Add to this the big prizes at a time when money was hard to come by, a Tour largely comprising young riders from impoverished backgrounds for whom bicycle racing was their one big chance to get ahead, and the passionate following cycling enjoyed, and you had the perfect recipe for a desperate, high-stakes, win-at-all-costs mentality, especially given the generally tolerant views on alcohol and drugs in those days.

After World War II came the amphetamines. Devised to keep soldiers awake and aggressive through long hours of battle, they were equally handy for bicycle racers competing in the world's longest and toughest race.

So what makes the Armstrong story any different, his road to redemption any rougher? For one thing, none of the aforementioned riders were ever the point man for what the

U.S. Anti-Doping Agency

has described in a thousand-page report as the most sophisticated, cynical, and far-reaching doping program the world of sport has ever seen—one whose secrecy and efficiency was maintained by ruthlessness, bullying, fear, and intimidation.

Somewhere along the line, the casualness of cheating in the past evolved into an almost Frankenstein sort of science in which cyclists, aided by creepy doctors and trainers, were receiving blood transfusions in hotel rooms and tinkering around with their bodies at the molecular level many months before they ever lined up for a race.

To be sure, Armstrong didn't invent all of this, any more than he invented original sin—nor was he acting alone. But with his success, money, intelligence, influence, and cohort of thousand-dollar-an-hour lawyers—and the way he used all this to prop up the Lance brand and the Lance machine at any cost—he became the poster boy and lightning rod for all that went wrong with cycling, his high profile eclipsing even the heads of the

Union Cycliste Internationale

, the global cycling union, who richly deserve their share of the blame.

It's not his PED popping that is the hard-to-forgive part of the Lance story. Armstrong cheated better than his peers, that's all.