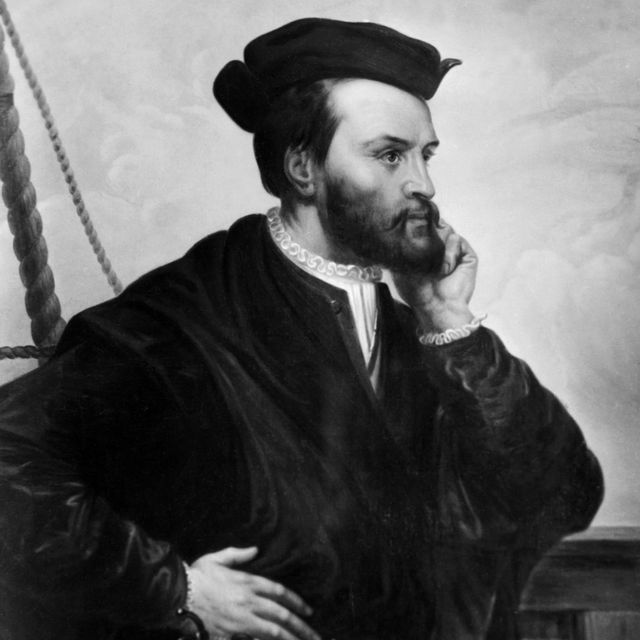

Jacques Cartier

French explorer Jacques Cartier is known chiefly for exploring the St. Lawrence River and giving Canada its name.

(1491-1557)

Who Was Jacques Cartier?

French navigator Jacques Cartier was sent by King Francis I to the New World in search of riches and a new route to Asia in 1534. His exploration of the St. Lawrence River allowed France to lay claim to lands that would become Canada. He died in Saint-Malo in 1557.

Early Life and First Major Voyage to North America

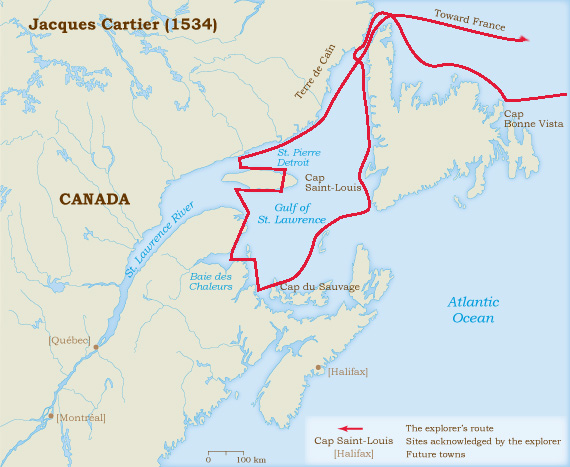

Born in Saint-Malo, France on December 31, 1491, Cartier reportedly explored the Americas, particularly Brazil, before making three major North American voyages. In 1534, King Francis I of France sent Cartier — likely because of his previous expeditions — on a new trip to the eastern coast of North America, then called the "northern lands." On a voyage that would add him to the list of famous explorers, Cartier was to search for gold and other riches, spices, and a passage to Asia.

Cartier sailed on April 20, 1534, with two ships and 61 men, and arrived 20 days later. He explored the west coast of Newfoundland, discovered Prince Edward Island and sailed through the Gulf of St. Lawrence, past Anticosti Island.

Second Voyage

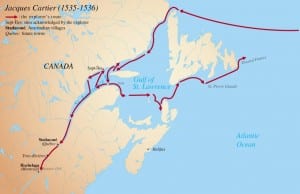

Upon returning to France, King Francis was impressed with Cartier’s report of what he had seen, so he sent the explorer back the following year, in May, with three ships and 110 men. Two Indigenous peoples Cartier had captured previously now served as guides, and he and his men navigated the St. Lawrence, as far as Quebec, and established a base.

In September, Cartier sailed to what would become Montreal and was welcomed by the Iroquois who controlled the area, hearing from them that there were other rivers that led farther west, where gold, silver, copper and spices could be found. Before they could continue, though, the harsh winter blew in, rapids made the river impassable, and Cartier and his men managed to anger the Iroquois.

So Cartier waited until spring when the river was free of ice and captured some of the Iroquois chiefs before again returning to France. Because of his hasty escape, Cartier was only able to report to the king that untold riches lay farther west and that a great river, said to be about 2,000 miles long, possibly led to Asia.

Third Voyage

In May 1541, Cartier departed on his third voyage with five ships. He had by now abandoned the idea of finding a passage to the Orient and was sent to establish a permanent settlement along the St. Lawrence River on behalf of France. A group of colonists was a few months behind him this time.

Cartier set up camp again near Quebec, and they found an abundance of what they thought were gold and diamonds. In the spring, not waiting for the colonists to arrive, Cartier abandoned the base and sailed for France. En route, he stopped at Newfoundland, where he encountered the colonists, whose leader ordered Cartier back to Quebec. Cartier, however, had other plans; instead of heading to Quebec, he sneaked away during the night and returned to France.

There, his "gold" and "diamonds" were found to be worthless, and the colonists abandoned plans to found a settlement, returning to France after experiencing their first bitter winter. After these setbacks, France didn’t show any interest in these new lands for half a century, and Cartier’s career as a state-funded explorer came to an end. While credited with the exploration of the St. Lawrence region, Cartier's reputation has been tarnished by his dealings with the Iroquois and abandonment of the incoming colonists as he fled the New World.

Cartier died on September 1, 1557, in Saint-Malo, France.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Jacques Cartier

- Birth Year: 1491

- Birth date: December 31, 1491

- Birth City: Saint-Malo, Brittany

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: French explorer Jacques Cartier is known chiefly for exploring the St. Lawrence River and giving Canada its name.

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1557

- Death date: September 1, 1557

- Death City: Saint-Malo, Brittany

- Death Country: France

- If the soil were as good as the harbors, it would be a blessing.

- [T]he land should not be called the New Land, being composed of stones and horrible rugged rocks; for along the whole of the north shore I did not see one cartload of earth and yet I landed in many places.

- Out of 110 that we were, not 10 were well enough to help the others, a thing pitiful to see.

- Today was our first day at sea. The weather was good, no clouds at the horizon and we are praying for a smooth sail.

- We set sail again trying to discover more wonders of this new world.

- Today I did something great for my country. We have taken over the land. Long live the King of France!

- I'm anxious to see what lies ahead. Every day we are getting deeper and deeper inside the continent, which increases my curiosity.

- Today I have completed my second voyage, which I can say had thought me a lot about how different things are in this world and how people start building up communities according to their common beliefs.

- The world is big and still hiding a lot.

- There arose such stormy and raging winds against us that we were constrained to come to the place again from whence we were come.

- I am inclined to believe that this is the land God gave to Cain.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

Jacques Cartier Facts, Biography, Accomplishments, Voyages

Published: Jun 4, 2012 · Modified: Nov 11, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

Jacques Cartier (December 31, 1491 – September 1, 1557) was the first French Explorer to explore the New World. He explored what is now Canada and set the stage for the great explorer and navigator Samuel de Champlain to begin colonization of Canada.

Cartier was the first European to discover and create a map of the St. Lawrence River. The St. Lawrence River would play an important role in the New World during the French and Indian War, the American Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the colonization of America.

Early Life of Jacques Cartier

First voyage, 1534, second voyage, 1535–1536, third voyage, 1541–1542, later life and death.

- Cartier was born in 1491 in Saint-Malo. During his early childhood, he would hear stories of the great Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and the exploits of the Spanish Conquistadors .

- His homeland, France, was relatively inactive in the exploits of the New World. Instead, it was embroiled in the European wars with the Holy Roman Empire, England, and Spain. Cartier grew and began to study navigation and, over time, became an excellent mariner.

- In a feudal society, talents were often overlooked and superseded by political standing. Cartier did not get the attention he deserved until he married Mary Catherine, who was a daughter in a wealthy and politically influential family.

- In 1534, Jacques Cartier was brought to the court of King Francis I. King Francis I ruled France during the reign of Charles V in the Holy Roman Empire and Henry VIII of England.

- He was a talented Monarch and ambitious for great treasure. 10 years prior to Cartier, he had asked Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the eastern coast of North America but had not formally commissioned him.

- Cartier set sail with a commission from King Francis I in 1534 with hopes of finding a pathway through the New World and into Asia.

- Jacques Cartier sailed across the ocean, landed around Newfoundland, and began exploring the area around the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River. While exploring, he came across two Indian tribes, the Mi'kmaq and the Iroquois. Initially, relations with the Iroquois were positive as he began to establish trade with them. However, Cartier then planted a large cross and claimed the land for the King of France.

- The Iroquois understood the implications and began to change their mood. In response, Cartier kidnapped two of the captain's sons. The Iroquois captain and Cartier agreed that the sons could be taken as long as they were returned with European goods to trade. Cartier then returned to his ships and began his voyage home. He believed that he had found the coast of Asia.

- After his return from his first voyage, Cartier received much praise from Francis I and was granted another voyage, which he left the next year. He left France on May 19 with three ships, 110 men, and the two natives he promised to return to the Iroquois captain.

- This time, when he arrived at the St. Lawrence River, he sailed up the river in what he believed to be a pathway into Asia. He did not reach Asia but instead came into contact with Chief Donnacona, who ruled from the Iroquois capital, Stadacona.

- Cartier continued up the St. Lawrence, believing that it was the Northwest passage to the east. He came across the Iroquois city of Hochelaga and was not able to go much further. The St. Lawrence waters became rapids and were too harsh for ships.

- His expedition left Cartier unable to return to France before the coming of winter. He stayed among the people of Hochelaga and then sailed back to Stadacona around mid-October. He most likely set up winter camp here. During his encampment, scurvy broke out among the Iroquois and soon infected the European explorers. The prognosis was dim until the Iroquois revealed a remedy for scurvy. Bark from a white spruce boiled in water would rid them of the disease.

- Cartier and his men used an entire white spruce to concoct the remedy. The remedy would work and would save the expedition from failure.

- Cartier left Canada for France in May of 1536. Chief Donnacona traveled to France with him to tell King Francis of the great treasures to be found. Jacques Cartier arrived in France on July 15, 1536. His second voyage had made him a wealthy and affluent man.

- Jacques Cartier's third voyage was a debacle. It began with King Francis commissioning Cartier to found a colony and then replacing Cartier with a friend of his, Huguenot explorer Roberval. Cartier was placed as Roberval's chief navigator. Cartier and Roberval left France in 1541.

- Upon reaching the St. Lawrence, Roverval waited for supplies and sent Cartier ahead to begin construction on the settlement. Cartier anchored at Stadacona and once again met with the Iroquois. While they greeted him with much happiness, Cartier did not like how many of them there were and chose to sail down the river a bit more to find a better spot to construct the settlement. He found the spot and began construction and named it Charlesbourg-Royal.

- After fortifying the settlement, Cartier set out to search for Saguenay. His search was again halted by winter, and the rapids of the Ottawa River forced him to return to Charlesbourg-Royal. Upon his arrival, he found out that the Iroquois Indians were no longer friendly to the Europeans. They attacked the settlement and left 35 of the settlers dead. Jacques Cartier believed that he had insufficient manpower to defend the settlement and search for the Saguenay Kingdom. He also believed that he and his men had found diamonds and gold and had stashed them on two ships.

- Cartier set sail for France in June of 1542. Along the way, he located Roberval and his ships along the coast of Newfoundland. Roberval insisted that Cartier stay and continue with him to the settlement and to help find the Kingdom of Saguenay, and Carter pretended to oblige. Cartier waited, and when the perfect night came, he and his ships full of diamonds and gold left Roberval and returned to France. Roberval continued to Charlesbourg-Royal but abandoned it 2 years later after harsh winters, disease, and the hostile Iroquois Indians.

- Upon returning to France, Cartier would learn that the diamonds he believed to have found were nothing more than mineral deposits. This ended the career of Jacques Cartier.

- Jacques Cartier retired to Sain-Malo, where he served as an interpreter of the Portuguese language. A typhus epidemic broke out in 1557 and claimed the life of the great explorer. Cartier died 15 years after his last voyage to the New World.

- While Cartier's missions did not establish a permanent settlement in Canada, it laid the foundation for Samuel de Champlain.

Biography of Jacques Cartier, Early Explorer of Canada

Rischgitz / Stringer/ Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- Canadian Government

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.A., Political Science, Carleton University

Jacques Cartier (December 31, 1491–September 1, 1557) was a French navigator sent by French King Francis I to the New World to find gold and diamonds and a new route to Asia. Cartier explored what became known as Newfoundland, the Magdalen Islands, Prince Edward Island, and the Gaspé Peninsula, and was the first explorer to map the St. Lawrence River. He claimed what is now Canada for France.

Fast Facts: Jacques Cartier

- Known For : French explorer who gave Canada its name

- Born : Dec. 31, 1491 in Saint-Malo, Brittany, France

- Died : Sept. 1, 1557 in Saint-Malo

- Spouse : Marie-Catherine des Granches

Jacques Cartier was born on Dec. 31, 1491, in Saint-Malo, a historic French port on the coast of the English Channel. Cartier began to sail as a young man and earned a reputation as a highly-skilled navigator, a talent that would come in handy during his voyages across the Atlantic Ocean.

He apparently made at least one voyage to the New World, exploring Brazil , before he led his three major North American voyages. These voyages—all to the St. Lawrence region of what is now Canada—came in 1534, 1535–1536, and 1541–1542.

First Voyage

In 1534 King Francis I of France decided to send an expedition to explore the so-called "northern lands" of the New World. Francis was hoping the expedition would find precious metals, jewels, spices, and a passage to Asia. Cartier was selected for the commission.

With two ships and 61 crewmen, Cartier arrived off the barren shores of Newfoundland just 20 days after setting sail. He wrote, "I am rather inclined to believe that this is the land God gave to Cain."

The expedition entered what is today known as the Gulf of St. Lawrence by the Strait of Belle Isle, went south along the Magdalen Islands, and reached what are now the provinces of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. Going north to the Gaspé peninsula, he met several hundred Iroquois from their village of Stadacona (now Quebec City), who were there to fish and hunt for seals. He planted a cross on the peninsula to claim the area for France, although he told Chief Donnacona it was just a landmark.

The expedition captured two of Chief Donnacona's sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, to take along as prisoners. They went through the strait separating Anticosti Island from the north shore but did not discover the St. Lawrence River before returning to France.

Second Voyage

Cartier set out on a larger expedition the next year, with 110 men and three ships adapted for river navigation. Donnacona's sons had told Cartier about the St. Lawrence River and the “Kingdom of the Saguenay” in an effort, no doubt, to get a trip home, and those became the objectives of the second voyage. The two former captives served as guides for this expedition.

After a long sea crossing, the ships entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence and then went up the "Canada River," later named the St. Lawrence River. Guided to Stadacona, the expedition decided to spend the winter there. But before winter set in, they traveled up the river to Hochelaga, the site of present-day Montreal. (The name "Montreal" comes from Mount Royal, a nearby mountain Cartier named for the King of France.)

Returning to Stadacona, they faced deteriorating relations with the natives and a severe winter. Nearly a quarter of the crew died of scurvy, although Domagaya saved many men with a remedy made from evergreen bark and twigs. Tensions grew by spring, however, and the French feared being attacked. They seized 12 hostages, including Donnacona, Domagaya, and Taignoagny, and fled for home.

Third Voyage

Because of his hasty escape, Cartier could only report to the king that untold riches lay farther west and that a great river, said to be 2,000 miles long, possibly led to Asia. These and other reports, including some from the hostages, were so encouraging that King Francis decided on a huge colonizing expedition. He put military officer Jean-François de la Rocque, Sieur de Roberval, in charge of the colonization plans, although the actual exploration was left to Cartier.

War in Europe and the massive logistics for the colonization effort, including the difficulties of recruiting, slowed Roberval. Cartier, with 1,500 men, arrived in Canada a year ahead of him. His party settled at the bottom of the cliffs of Cap-Rouge, where they built forts. Cartier started a second trip to Hochelaga, but he turned back when he found that the route past the Lachine Rapids was too difficult.

On his return, he found the colony under siege from the Stadacona natives. After a difficult winter, Cartier gathered drums filled with what he thought were gold, diamonds, and metal and started to sail for home. But his ships met Roberval's fleet with the colonists, who had just arrived in what is now St. John's, Newfoundland .

Roberval ordered Cartier and his men to return to Cap-Rouge, but Cartier ignored the order and sailed for France with his cargo. When he arrived in France, he found that the load was really iron pyrite—also known as fool's gold—and quartz. Roberval's settlement efforts also failed. He and the colonists returned to France after experiencing one bitter winter.

Death and Legacy

While he was credited with exploring the St. Lawrence region, Cartier's reputation was tarnished by his harsh dealings with the Iroquois and by his abandoning the incoming colonists as he fled the New World. He returned to Saint-Malo but got no new commissions from the king. He died there on Sept. 1, 1557.

Despite his failures, Jacques Cartier is credited as the first European explorer to chart the St. Lawrence River and to explore the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He also discovered Prince Edward Island and built a fort at Stadacona, where Quebec City stands today. And, in addition to providing the name for a mountain that gave birth to "Montreal," he gave Canada its name when he misunderstood or misused the Iroquois word for village, "kanata," as the name of a much broader area.

- " Jacques Cartier Biography ." Biography.com.

- " Jacques Cartier ." History.com.

- " Jacques Cartier: French Explorer ." Encyclopedia Brittanica.

- A Timeline of North American Exploration: 1492–1585

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- Captain James Cook

- The Florida Expeditions of Ponce de Leon

- Biography of Ferdinand Magellan, Explorer Circumnavigated the Earth

- Amerigo Vespucci, Italian Explorer and Cartographer

- The Story of How Canada Got Its Name

- Biography and Legacy of Ferdinand Magellan

- Explorers and Discoverers

- Biography of Christopher Columbus

- Queen Elizabeth's Royal Visits to Canada

- Profile of Prince Henry the Navigator

- French and Indian War: Battle of Quebec (1759)

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- Biography of Juan Ponce de León, Conquistador

- Biography of Juan Sebastián Elcano, Magellan's Replacement

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Allaire, Bernard. "Jacques Cartier". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 09 July 2020, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier. Accessed 31 March 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 09 July 2020, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier. Accessed 31 March 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Allaire, B. (2020). Jacques Cartier. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Allaire, Bernard. "Jacques Cartier." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2013; Last Edited July 09, 2020.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2013; Last Edited July 09, 2020." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Jacques Cartier," by Bernard Allaire, Accessed March 31, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Jacques Cartier," by Bernard Allaire, Accessed March 31, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Jacques Cartier

Article by Bernard Allaire

Published Online August 29, 2013

Last Edited July 9, 2020

Jacques Cartier, navigator (born between 7 June and 23 December 1491 in Saint-Malo, France; died 1 September 1557 in Saint-Malo, France). From 1534 to 1542, Cartier led three maritime expeditions to the interior of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River . During these expeditions, he explored, but more importantly accurately mapped for the first time the interior of the river, from the Gulf to Montreal ( see also History of Cartography in Canada ). For this navigational prowess, Cartier is still considered by many as the founder of “Canada.” At the time, however, this term described only the region immediately surrounding Quebec . Cartier’s upstream navigation of the St. Lawrence River in the 16th century ultimately led to France occupying this part of North America.

Voyages to the Americas

Jacques Cartier’s early life is very poorly documented. He was likely employed in business and navigation from a young age. Like his countrymen, Cartier probably sailed along the coast of France, Newfoundland and South America (Brazil), first as a sailor and then as an officer. Following the annexation of Brittany to the kingdom of France, King François 1 chose Cartier to replace the explorer Giovanni da Verrazano . Verrazano had died on his last voyage.

First Voyage (1534)

Jacques Cartier’s orders for his first expedition were to search for a passage to the Pacific Ocean in the area around Newfoundland and possibly find precious metals. He left Saint-Malo on 20 April 1534 with two ships and 61 men. They reached the coast of Newfoundland 20 days later. During his journey, Cartier passed several sites known to European fishers. He renamed these places or noted them on his maps. After skirting the north shore of Newfoundland , Cartier and his ships entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence by the Strait of Belle Isle and travelled south, hugging the coast of the Magdalen Islands on 26 June. Three days later, they reached what are now the provinces of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick . He then navigated towards the west, crossing Chaleur Bay and reaching Gaspé , where he encountered Iroquoian lndigenous people from the region of Quebec . They had come to the area for their annual seal hunt. After planting a cross and engaging in some trading and negotiations, Cartier’s ships left on 25 July. Before leaving, Cartier abducted two of Iroquoian chief Donnacona’s sons. They returned to France by following the coast of Anticosti Island and re-crossing the Strait of Belle Isle.

Second Voyage (1535-6)

The expedition of 1535 was more important than the first expedition. It included 110 people and three medium-sized ships. The ships were called the Grande Hermine (the Great Stoat), the Petite Hermine (the Lesser Stoat) and the Émérillon (the Merlin). The Émérillon had been adapted for river navigation. They left Brittany in mid-May 1535 and reached Newfoundland after a long, 50-day crossing. Following the itinerary from the previous year, they entered the Gulf , then travelled the “Canada River” (later named the St. Lawrence River ) upstream. One of chief Donnacona’s sons guided them to the village of Stadacona on the site of what is now the city of Quebec . Given the extent of their planned explorations, the French decided to spend the winter there and settled at the mouth of the St. Charles River. Against the advice of chief Donnacona, Jacques Cartier decided to continue sailing up the river towards Hochelaga , now the city of Montreal . Cartier reached Hochelaga on 2 October 1535. There he met other Iroquoian people, who tantalized Cartier with the prospect of a sea in the middle of the country. By the time Cartier returned to Stadacona (Quebec), relations with the Indigenous people there had deteriorated. Nevertheless, they helped the poorly organized French to survive scurvy thanks to a remedy made from evergreen trees ( see also Indigenous Peoples’ Medicine in Canada ). When spring came, the French decided to return to Europe. This time, Cartier abducted chief Donnacona himself, the two sons, and seven other Iroquoian people. The French never returned Donnacona and his people to North America. ( See also Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada. )

Third Voyage (1541-2)

The war in Europe led to a delay in returning to Canada. In addition, the plans for the voyage were changed. This expedition was to include close to 800 people and involve a major attempt to colonize the region. The explorations were left to Jacques Cartier, but the logistics and colonial management of the expedition were entrusted to Jean-François de La Rocque , sieur de Roberval. Roberval was a senior military officer who was responsible for recruitment, loading weapons onto the ships, and bringing on craftsmen and a number of prisoners. Just as the expedition was to begin, delays in the preparations and the vagaries of the war with Spain meant that only half the personnel (led by Cartier) were sent to Canada in May 1541 by Roberval. Roberval eventually came the following year. Cartier and his men settled the new colony several kilometres upstream from Quebec at the confluence of the Cap Rouge and St. Lawrence rivers. While the colonists and craftsmen built the forts, Cartier decided to sail toward Hochelaga . When he returned, a bloody battle had broken out with the Iroquoian people at Stadacona .

Return to France

In a state of relative siege during the winter, and not expecting the arrival of Jean-François de La Rocque , sieur de Roberval until spring, Jacques Cartier decided to abandon the colony at the end of May. He had filled a dozen barrels with what he believed were precious stones and metal. At a stop in St. John’s , Newfoundland, however, Cartier met Roberval’s fleet and was given the order to return to Cap Rouge. Refusing to obey, Cartier sailed toward France under the cover of darkness. The stones and metal that he brought back turned out to be worthless and Cartier was never reimbursed by the king for the money he had borrowed from the Breton merchants. After this misadventure, he returned to business. Cartier died about 15 years later at his estate at Limoilou near Saint-Malo. He kept his reputation as the first European to have explored and mapped this part of the Americas, which later became the French axis of power in North America.

- St Lawrence

Further Reading

Marcel Trudel, The Beginnings of New France, 1524-1663 (1973).

External Links

Watch the Heritage Minute about French explorer Jacques Cartier from Historica Canada. See also related online learning resources.

Exploring the Explorers: Jacques Cartier Teacher guide for multidisciplinary student investigations into the life of explorer Jacques Cartier and his role in Canadian history. From the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Indigenous languages in canada, enslavement of indigenous people in canada, indigenous perspectives education guide.

Virtual museum of New France

- Virtual museum of new France

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

The Explorers

- Economic Activities

- Useful links

- North America Before New France

- From the Middle Ages to the Age of Discovery

- Founding Sites

- French Colonial Expansion and Franco-Amerindian Alliances

- Other New Frances

- Other Colonial Powers

- Wars and Imperial Rivalries

- Governance and Sites of Power

Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Basque Whalers

- Industrial Development

- Commercial Networks

- Immigration

- Social Groups

- Religious Congregations

- Pays d’en Haut and Louisiana

- Entertainment

- Communications

- Health and Medicine

- Vernacular Architecture in New France

We do not know how Jacques Cartier learned the art of navigation, but Saint-Malo, the town where he was born between the summer and winter of 1491, was at the time one of the most important ports in Europe. In 1524 he probably accompanied Giovanni da Verrazzano on unofficial explorations initiated by the king of France. Some ten years later, Jacques Cartier was a sufficiently experienced navigator to be asked by Francis I to undertake the official exploration of North America. There is no doubt that he was already familiar with the sea route that he took in 1534.

To the New Lands

On March 19, 1534, Cartier was assigned the mission of “undertaking the voyage of this kingdom to the New Lands to discover certain islands and countries where there are said to be great quantities of gold and other riches”. The following April 20, the navigator from Saint-Malo cast off with two ships and a crew of 61. Twenty days later he reached Newfoundland. The exploration began in an area frequented by Breton fishermen: from the Baie des Châteaux (Strait of Belle Isle) to southern Newfoundland. After erecting a cross at Saint-Servan on the north coast of the Gulf, Cartier tacked to the south. He first encountered the Magdalen Islands, and then set course for present-day Prince Edward Island, failing to notice that it was in fact an island.

A Lie and A Claiming of Possession

Cartier then moved on to Chaleur Bay, where he encountered some Micmacs on July 7. The talks were accompanied by a swapping of items, which history has recorded as the first act of trade between the French and Amerindians. Soon after, Cartier reached Gaspé Bay.

More than 200 Iroquois from Stadacona (Québec) were on the peninsula to fish. Initially trusting and cordial, relations were tarnished when Jacques Cartier claimed possession of the territory on July 24. The 30-foot cross he erected at Pointe-Penouille seemed improper to Donnacona, the Native chief. Fearing the consequences of this discontent, Cartier lied, describing the cross as an insignificant landmark.

Jacques Cartier in Gaspé On the 25th he left the Gaspé area, heading for the Gulf of St. Lawrence. After navigating the strait separating Anticosti Island from the north shore, he set off again for Saint-Malo, where he landed on September 5. The St. Lawrence River had not been discovered.

Revelations of the Amerindian Guides

Jacques Cartier arrived in France with two precious trophies: Domagaya and Taignoagny, the sons of Donnacona, whom he had convinced to come with him. They told him of the St. Lawrence River and the “Kingdom of the Saguenay”, the objectives of his second voyage upon which he set forth on May 19, 1535. Cartier had been persuasive: his crew had doubled and he had command of three ships: the Grande Hermine, Petite Hermine and Émérillon.

Fifty days after putting to sea, a first vessel laid anchor off the shores of Newfoundland. On July 26 the convoy was reunited, and exploration could begin again. On August 10, the day of St. Lawrence, the explorer gave the saint’s name to a little bay. Cartographers later applied it to the the “great river of Hochelaga and route to Canada” leading to the interior of the continent, “so long that no man has seen its end”.

From the Saguenay to Hochelaga

Sailing along the river to Stadacona (Québec), the ships passed Anticosti Island and the mouth of the Saguenay. Cartier established his headquarters on the Sainte-Croix (Saint-Charles) river, and five days later boarded the Émérillon to travel to Hochelaga (Montreal). Leaving the ship in Lake Saint-Pierre, he proceeded in a small craft to the Iroquois village, where he arrived on October 2.

There were nearly 2,000 people living there. The island and village were overlooked by a mountain, which he named mount Royal. He was taken there by his hosts, who spoke to him of the riches of the west, and again of the “Kingdom of the Saguenay”. The rapids north and south of Montreal Island prevented him from continuing his route to the west. Cartier had to return to harbour on the Saint-Charles river, where he found that relations with the Iroquois had become more acrimonious. The threat of an early winter lay before the Frenchmen.

Isolation, Cold and Scurvy

From mid-November, the ships were imprisoned in the ice. December began with an epidemic of scurvy. The Iroquois, the first affected, were slow in delivering up the secret of anedda, a white cedar tea which would save them. Of the 100 Frenchmen afflicted, 25 died.

On May 3, Cartier planted a cross on the site where he had just wintered. The same day, he seized about ten Iroquois, one of them Donnacona, the only one who was able to “relate to the King the marvels he had seen in the western lands”.

The voyage back began three days later, without the Petite Hermine. Following a swerve along the Newfoundland coast, Jacques Cartier discovered the strait which bears the name of the explorer Giovanni Caboto. On July 16, 1536, Cartier was again in Saint-Malo.

The Colonization of Canada

On October 17, 1540, Francis I ordered the Breton navigator to return to Canada to lend weight to a colonization project of which he would be “captain general”. But on January 15, 1541 Cartier was supplanted by Jean-François de La Roque de Roberval, a Huguenot courtier.

Authorized to leave by Roberval, who was awaiting the delivery of artillery and merchandise, Jacques Cartier departed from Saint-Malo on May 23, 1541. He led five vessels “well provisioned with victuals for two years”, including the Grande Hermine, Émérillon, Saint-Brieux and Georges. There were 1500 people travelling with him. The crossing took more than three months.

With the exception of one little girl, all the Iroquois died in France. Cartier admitted the death of Donnacona, but claimed that the others “had remained in France where they were living as great lords; they had married and had no desire to return to their country”.

Being no longer welcome in Stadacona, the colonists settled at the foot of Cap Rouge (Cap Diamant), named Charlesbourg Royal. The experience was a disaster. In June 1542 Cartier left the St. Lawrence valley with the survivors. At Newfoundland he met with Roberval’s group, which had only left La Rochelle in April. The night after their encounter, Cartier placed the entreprise in jeopardy by slipping away from his leader. He landed in Saint-Malo in September.

Jacques Cartier would never return to Canada. As for Roberval, he continued on to Charlesbourg Royal, which he renamed France-Roi. After putting up with the climate, scurvy, quarrelling and adversity, his colony was extinguished in 1543 with the repatriation of those who survived.

Jacques Cartier

See France in the Age of Exploration . See also Indian Wars Time Table .

As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

I’ll take the survey now.

Remind me later.

Don’t show me this message again.

I have already taken the questionnaire

- Hide Sidebar

- First Paragraph

- Bibliography

- Find Out More

- How to cite

- Back to top

DCB/DBC News

New biographies, minor corrections, biography of the day.

d. 31 March 1839 at Malignant Cove, N.S.

Confederation

Responsible government, sir john a. macdonald, from the red river settlement to manitoba (1812–70), sir wilfrid laurier, sir george-étienne cartier, the fenians, women in the dcb/dbc.

Winning the Right to Vote

The Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences of 1864

Introductory essays of the dcb/dbc, the acadians, for educators.

Exploring the Explorers

The War of 1812

Canada’s wartime prime ministers, the first world war.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/MIKAN 2835981

CARTIER, JACQUES , navigator of Saint-Malo, first explorer of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1534, discoverer of the St. Lawrence River in 1535, commander of the settlement of Charlesbourg-Royal in 1541–42; b. probably some time between 7 June and 23 Dec. 1491 at Saint-Malo (Brittany), where he died in 1557.

Cartier had no doubt been going to sea since his youth, but nothing is known of his career before 1532. According to Lanctot, Cartier may have taken part in Verrazzano’s expeditions in 1524 and 1528. Cartier’s absences from France which coincide with the voyages of the celebrated Florentine, the objective assigned to Cartier in 1534, his point of arrival in Newfoundland which corresponds to the final point reached on the 1524 voyage, a Danish map of 1605, and a statement of the Jesuit Pierre Biard in his Relation for the year 1614 – from all these Lanctot concludes that Cartier sailed along the North American coast in 1524. He further states that Cartier, after Verrazzano’s death, took command of the ship to return to France.

Several objections militate against this theory: if Cartier was absent from Saint-Malo during Verrazzano’s voyages, he could easily have been elsewhere than on the Dauphine ; moreover the expedition set out from Normandy, and one can hardly imagine a Breton joining forces, at that time, with the shipowners of Dieppe. Why does Cartier, in the accounts of his travels, never allude to Verrazzano or to the coast visited in 1524? When he compares the natives or the produce of Canada with those of Brazil, why does he never mention those of the North American seaboard? If Cartier had an important post on board the Dauphine , why does his name not appear in the Verrazzanian toponymy which recalls so many of the people associated with the Florentine? Finally, why do the French maps which rely upon Cartier for the valley of the St. Lawrence reject the Verrazzanian toponymy and utilize systematically the Spanish one? Lanctot’s thesis is interesting, although it remains unproven and adds nothing certain to our knowledge of Cartier.

When in 1532 Jean Le Veneur, bishop of Saint-Malo and abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel, suggested to François I that an expedition be sent to the New World, he asserted that Cartier had already been to Brazil and to “Newfoundland.” In fact Cartier’s accounts do include several allusions to Brazil which are not merely recollections of things read; as for Newfoundland, Cartier knew the surrounding regions: a month before his departure he was aware that he was expected to reach the “Baie des Châteaux” (Strait of Belle-Isle), and he went directly there as if it were a familiar stopping-place.

The commission granted to Cartier in 1534 has not been located, but an order from the king, in March of the same year, enlightens us as to the objective of the voyage: “to discover certain islands and lands where it is said that a great quantity of gold, and other precious things, are to be found.” The 1534 account suggests a second objective: the route to Asia. To those who credit Cartier, on this first voyage, with a concern for missionary work, Lionel Groulx’s answer is: “Gold, the gateway to Cathay! If there is a mystique in all this, to use a word which is so debased today, it is a mystique of merchants, behind which looms a political rivalry.” The 1534 account mentions no priest engaged in evangelization among the natives; it would moreover have been useless, because of the linguistic barrier. Although the ship’s muster-roll has not been found, one may surmise that at least one priest was on board; when Bishop Le Veneur had proposed Cartier he had undertaken to supply the chaplains, and the account of the voyage alludes to the singing of mass.

Cartier set off from Saint-Malo on 20 April 1534, with 2 ships and 61 men. Favoured by “good weather,” he crossed the Atlantic in 20 days. He visited places already known and named, from the cape of “Bonne Viste” to the Baie des Châteaux; then he entered the bay which had been set as the first stage in his journey. Ten leagues away, in the interior, was the port of Brest, a depot for supplying the codfishermen with water and wood. One hundred miles to the west of Belle-Isle, Cartier encountered a ship from La Rochelle; he directed it back on to its course. Cartier was not yet in a totally unknown world, but he freely assigned names to the geographical features of the north coast: Île Sainte-Catherine; Toutes-Isles; Havre Saint-Antoine; Havre Saint-Servan, where he set up his first cross; Rivière Saint-Jacques; Havre Jacques-Cartier. For the land which he saw he had the utmost contempt: “along the whole of the north shore, I did not see one cart-load of earth,” it was “the land God gave to Cain.” On 15 June he steered “towards the south” and entered unexplored regions. He went along the west coast of Newfoundland, distributing French names, and reached what is today Cabot Strait, but he did not perceive that it was a navigable channel and turned westward.

He came across islands which appeared fertile to him by comparison with Newfoundland, among them Île Brion where he perhaps set up another cross, and on 26 June he reached the Îles de la Madeleine, which he assumed to be the beginning of the mainland. On the evening of 29 June he sighted another land, “the best-tempered region one can possibly see, and the heat is considerable”; he had discovered Prince Edward Island, without however being able to determine that it was an island.

Next, he explored bays that were disappointing, openings that held continual promise of being the passage to Asia, but which grew narrower as he advanced. To the southern tip of the “baye de Chaleurs” he gave the name of Cap d’Espérance, “for the hope we had of finding here a strait.” From 4 to 9 July he made a systematic investigation, only to conclude that no passage existed, “whereat we were grieved and displeased.” On 14 July he entered the Baie de Gaspé (which remained unnamed in 1534). He stayed there for a considerable time, until 25 July, which permitted him to establish some very important contacts with the Indians.

They were not the first natives whom he had encountered. On 12 or 13 June he had seen Indians in the “land of Cain”; they had come from inland to hunt the seal, and they have been identified by some as Beothuks, who are now extinct. At the beginning of July he had seen others on the Prince Edward Island coast, and on 7 July, in the Baie des Chaleurs, he had traded in furs with natives, probably Micmacs. Those whom he met at Gaspé were Laurentian Iroquois, who had come down in great numbers for their annual fishing. This nation was master of the St. Lawrence and was to assume historical importance. The Iroquois gleefully accepted small gifts, and an alliance was concluded, with dancing and jubilation. On 24 July Cartier erected a cross 30 ft. high, bearing the arms of France, at Penouille Point. If the crosses at Saint-Servan and on Île Brion were rather in the nature of landmarks or beacons, this one was much more: it is clear from the importance of the ceremony that the cross was intended to indicate that the territory was being taken possession of in the name of François I. Chief Donnacona protested; he approached Cartier’s boat with his brother and three of his sons to harangue the strangers. A pretence was made of offering him an axe. As he was about to take it, the French held on to his craft and forced the Iroquois to come on board the ship. Cartier reassured them and obtained permission to take away with him two of Donnacona’s sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, promising to bring them back. There was feasting, followed by a most cordial leave-taking. Cartier left the Baie de Gaspé on 25 July with these two Indians, who would be able one day to act as interpreters.

He could have turned westward, but he turned eastward, thinking that the strait 40 miles wide between the Gaspé Peninsula and Anticosti was nothing more than “the coast [which] ran back forming a bay, in the shape of a semi-circle.” Cartier therefore missed discovering a river which would have taken him a long way into the interior of the continent. Until 29 July he sailed along the coast of Anticosti Island, and then around it; he took it for a peninsula. From 1 to 5 August he tried to find out whether he was in a bay or a waterway, and he finally realized that “the coast began to turn off towards the south-west.” Once again he had all but discovered the river, but bad weather intervened, and Cartier decided to withdraw. After meeting some Montagnais at Natashquan point, he set his course straight for Newfoundland, and on 15 August started on the trip home.

Cartier had been the first to go right round the gulf. Perhaps John Cabot , the Corte-Reals , and João Alvares Fagundes had seen it before him, but no document offers any proof. Cartier discovered the gulf, he drew a map of it, and he had caught a glimpse of the hinterland. True, his geographical knowledge was limited; he did not notice the passage between Newfoundland and Cape Breton, he thought the Îles de la Madeleine were the mainland, he did not discover the entry to the river. For Cartier, this sea possessed only one certain outlet, the Strait of Belle-Isle, and another possible one, to the north of Anticosti, which he did not have time to investigate.

The discovery of an inland sea, the exploration of a new country, an alliance with natives from the west, the immediate possibility of penetrating deeper, the assistance of two Indians who were learning to express themselves in French, all this made a second expedition worth while, even if Cartier had so far found neither gold nor metals. He was back in Saint-Malo on 5 Sept. 1534, and as early as 30 October he received a new commission to complete his discovery, François I paying 3,000 livres towards the undertaking.

In 1534 Cartier had had only 2 ships and 61 men; in 1535 he had 3 ships and a crew of some 110 men. On board the Grande Hermine , Cartier had the shipmaster Thomas Fromont as his assistant; he took with him Claude de Pontbriand (son of a Seigneur de Montréal, in Languedoc), Charles de La Pommeraye, Jehan Poullet, thought to be the author of the account of the second voyage, and a few gentlemen. Guillaume Le Marié sailed the Petite Hermine under the command of Macé Jalobert ; the captain of the Émérillon was Guillaume Le Breton Bastille and the navigator Jacques Maingart. The undertaking had brought together numerous relatives of Cartier and of his wife Catherine Des Granches: Étienne Noël, a nephew; Macé Jalobert, a brother-in-law; Antoine Des Granches, Jacques Maingart, and three other Maingarts; Michel Audiepvre; Michel Philipot; Guillaume and Antoine Aliecte; and Jacques Du Bog. Were there any chaplains? The ship’s muster-roll mentions dom Guillaume Le Breton, and dom Anthoine immediately following. The word “dom” was at that time applied only to secular priests, unless it is here the abbreviation for “Dominique.” Religious ceremonies were indeed performed on this voyage, but when Donnacona and his people asked for baptism (at a moment which it is difficult to specify), Cartier replied that he expected to bring priests with him on another voyage. Perhaps dom Le Breton and dom Anthoine were already dead? It is quite natural that chaplains should have accompanied such a large expedition, but no real proof of their presence can be found anywhere. Domagaya and Taignoagny were on the voyage also. During their eight and a half months’ stay in France they had learned French, but had not yet been baptized.

Cartier left Saint-Malo 19 May 1535 and reached the gulf once more after a long, 50-day crossing. He immediately resumed his quest, sailing along the north coast. To mark his route he set up a cross in a harbour to the west of Natashquan. He stopped in a bay which he called Saint-Laurent (now Sainte-Geneviève); the name was soon to be extended to the gulf, and then to the river. Finally, on 13 August, following the instructions of his two native guides, he passed the crucial point. There before him was the whole geography of the region: the Indians showed him “the way to the mouth of the great river of Hochelaga and the route towards Canada,” which narrowed continually as one went on; its waters, first salt then fresh, came from so great a distance that there was no record of any man ever having seen their source. Here at last, concluded Cartier, was the passage he was seeking.

He went up the river, examining the two shores as he advanced. He perceived on his right a “very deep and rapid” river which his guides told him was the route to the Saguenay, a kingdom where there was copper, and about which Donnacona was to tell wonderful tales. On 7 September Cartier reached the archipelago of Orléans, which was “where the province and territory of Canada begins,” the name Canada being applied then only to what is now Quebec. After feasting with Donnacona, Cartier decided to lay up his ships in the river Sainte-Croix (Saint-Charles), at the mouth of the stream called Lairet. Opposite rose the cape of Stadacona, where there was a village which was probably unfortified, after the Montagnais fashion, although it was inhabited by Iroquois.

Cartier was eager to get to Hochelaga, but the two native interpreters had already begun to scheme against the French. There was also some anxiety at Stadacona about this trip. Donnacona wanted to secure for himself the monopoly of the trade which would develop, since he hoped to escape from the domination exercised by Hochelaga over the Iroquois of the valley. He tried to detain Cartier by gifts, then by a display of witchcraft. Cartier, however, set out on 19 September on the Émérillon , but without interpreters, which greatly lessened the usefulness of his trip. He stopped at Achelacy (in the region of Portneuf), and formed an alliance with the local chieftain. He reached the lake which he called “Angoulême” (Saint-Pierre), left his ship at anchor, and went on in long-boats with some 30 men. On 2 October he arrived at Hochelaga, a town enclosed and fortified after the Iroquois style, near a mountain which he named Mont-Royal. He was given a joyous reception which even took on the air of a religious ceremony; to the Iroquois, who presented their sick to be cured, Cartier read the gospel according to St. John and the Passion of Christ. Without delaying further, he visited the rapids which blocked navigation to the west. The Indians explained to him by signs that other rapids obstructed the river and that a watercourse, by which one could reach the gold, silver, and copper of the Saguenay, flowed into the river from the north. But Cartier did not pursue his investigation; he left Hochelaga the next day, 3 October. On 7 October he stopped at the mouth of the “rivière de Fouez” (Saint-Maurice), and set up a cross there.

When Cartier returned to Stadacona, he found his men building a fort. The natives feigned joy on seeing him again, but their friendliness had vanished; new intrigues by the interpreters soon brought about a complete rupture. Relations were resumed only in November, in an atmosphere of mutual distrust.

Then came winter, the Laurentian winter which the Europeans were experiencing for the first time, and which furthermore was a severe one. From mid-November to mid-April the ships were icebound. The snow reached a height of four feet and more. The river froze as far as Hochelaga. Still more terrible than the winter was scurvy, which appeared among the natives of Stadacona in December; despite an attempt to set up a sanitary barrier against it, it attacked the French. By mid-February not more than 10 of Cartier’s 110 men were still well; 8 were dead, including the young Philippe Rougemont, on whom an autopsy was made. And the evil continued its ravages; 25 persons, all told, eventually died. Cartier and his men went in a procession to pray before an image of the Virgin, and Cartier promised to make a pilgrimage to Roc-Amadour. At last, by skilfully questioning Domagaya, who had had scurvy, Cartier learned the secret of the remedy: an infusion made from annedda (white cedar). The crew was quickly cured.

Cartier was eager to use his contacts with the natives to increase his knowledge. He is the first person to give us information on the religion and customs of the St. Lawrence valley Indians. The network of waterways was moreover beginning to take shape in his mind: the Richelieu, still unnamed, which came from “Florida”; the St. Lawrence, which was open to navigation for three months; to the north of Hochelaga, a river (the Ottawa) which led to great lakes and to a “freshwater sea”; great waterways which proved that the continental barrier was much broader than had been believed. All the wonderful stories that he heard about the fabulous kingdom of Saguenay, the legend of which was perhaps a relic of Norse traditions (unless the Mississippi basin was meant), were recorded by Cartier. This continent was already extremely rich in surprises!

When spring came they prepared to return to France. As his crew was not large enough, Cartier abandoned the Petite Hermine . Her remains were thought to have been found in 1842 and one portion was deposited with the Quebec Literary and Historical Society, the other being sent to Saint-Malo. But, as N.-E. Dionne has written, it has never been proved that this wreckage was that of the Petite Hermine .

Before leaving, Cartier wanted to strengthen the position of the French; the ethnic, linguistic, and political unity of the Laurentian valley already gave them an advantage, which was however endangered by the conduct of Donnacona and of his two sons. Cartier learned that a rival, Agona, was aspiring to power. A plan for a revolution became clear: to eliminate the ruling party on behalf of Agona. Cartier cunningly took advantage of a religious ceremony – the erection of a cross on the festival on 3 May – to capture Donnacona, the interpreters, and a few other natives. He appeased the crowd by promising to bring back Donnacona in 10 or 12 months, with lavish presents from the king.

On 6 May he left Sainte-Croix with his two ships and about ten Iroquois, including four children who had been given to him the previous autumn. In his cargo were a dozen pieces of gold and some furs. This time, as he sailed between Anticosti Island and the Gaspé Peninsula, he ascertained that the Îles de la Madeleine, then called the Araines, were in fact islands, and discovered between Newfoundland and Cape Breton the passage which he had not noticed in 1534. On 16 July 1536 he arrived back in Saint-Malo, after an absence of 14 months.

This second voyage had been much more profitable than the first: Cartier had discovered a river by means of which one could penetrate deeply into the continent; he had opened up a new access route to the gulf; he had seen the natural resources of the St. Lawrence and had got to know its inhabitants; he had returned with an old chieftain who boasted of having visited the fabulously wealthy country of the Saguenay; and he had gold.

Immediately on his return Cartier presented a report to François I; he spoke of a river 800 leagues long which might lead to Asia, and he got Donnacona to add his testimony. The king enthusiastically gave him the Grande Hermine .

However, the Saint-Malo navigator could not resume his explorations immediately. War broke out between François I and Charles V; Savoy effaced the thought of America. What became of Cartier? Lanctot ascribes to him a memoir of 1538, which outlines a colonization plan, but there is no documentary proof to lend support to this argument. Similarly Lanctot has attempted to forge a dramatic link between Cartier and the escape of the Irish rebel Gerald Fitzgerald, who styled himself a king. A first report from a spy states that Cartier went to Ireland to get Fitzgerald, a version which Lanctot hastily accepts; but in a second report drawn up by the same spy after a more extensive enquiry, Cartier’s role is limited to that of welcoming the refugee to Saint-Malo.

It was not until 17 Oct. 1540 that the king gave Cartier a commission for a third voyage. The discoverer was named captain-general of the new expedition, and he was to proceed to “Canada and Hochelaga, and as far as the land of Saguenay,” with individuals of “all kinds, arts and industries,” including some 50 men whom he was authorized to take from the prisons; exploration was to be carried out, and they were to live with the natives “if need be.” Cartier made ready: he arranged to have the 50 prisoners delivered to him, he asked certain spiritual favours from Rome, and he persuaded the king to intervene to hasten the recruitment of his crew.

On 15 Jan. 1541 a royal decision changed everything; the Protestant Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval received a commission which placed him instead of Cartier at the head of a great colonizing undertaking. Lanctot has argued that Cartier remained on an equal footing with Roberval, the one concerned with colonization, the other with navigation. Yet the text of the commission is clear: Roberval was named the king’s “lieutenant general,” the “chief, leader, captain” of the undertaking, with authority over all those who would be part of “the said undertaking, expedition and army,” and all were to take “oath of fealty” to obey him; moreover, in this commission the king annulled the one granted in October. Cartier became in truth Roberval’s subaltern.

Cartier was ready in May 1541, but Roberval had not yet received his artillery. As the king was anxious that Cartier should set sail at once, Roberval gave him “full authority to leave” and instructed him to represent him. Cartier made his will on 19 May and on 23 May put to sea with five ships, including the Grande Hermine and the Émérillon . A Spanish spy put the crew at 1,500 men. Among Cartier’s companions might be mentioned two brothers-in-law: Guyon Des Granches, Vicomte de Beaupré, and the pilot Macé Jalobert; a nephew, Étienne Noël; and the shipmaster Thomas Fromont, dit La Bouille, who was to die during this voyage. None of the Iroquois whom he had brought to France in 1536 returned to Canada; they had all died, except for a little girl.

On 23 Aug. 1541 Cartier reappeared before Stadacona. The Indians received him with numerous demonstrations of joy. Cartier announced Donnacona’s death, but stated that the other Iroquois were living in France like lords and did not want to return, which must have delighted Agona. The friendly relations nonetheless did not last. The abandonment of the Sainte-Croix site can no doubt be explained by this mutual distrust. Cartier went up the river and established himself at the western extremity of the cape, at the mouth of the Rivière du Cap-Rouge. The settlement was first called “Charlesbourg-Royal.” This site appeared much more favourable than the first one; moreover white cedar was found there, and especially stones which were thought to be diamonds (hence the name Cap aux Diamants), and “certain leaves of fine gold.”

On 2 September Cartier despatched Jalobert and Noël, with two ships, to France, to make a report; then he began two forts, one at the base of the cape, the other at the top. On the seventh he left the settlement under the command of the Vicomte de Beaupré and sailed for Hochelaga, greeting his friend the chieftain of Achelacy on the way and entrusting to him two boys so that they could be taught the language. They were the first two Europeans to become pupils of the natives. Cartier’s intention was to examine the Hochelaga rapids in order to be able to clear them the following spring. The Indians proved to be affable, as they were in 1535, but Cartier had no interpreters. He made no progress in his knowledge of the hinterland, but persisted in his hypothesis of 1535.

When he returned, Cartier noticed that the Iroquois’ distrust was increasing. Even the chieftain of Achelacy abandoned him. The French made ready to defend themselves. As the account of this voyage breaks off suddenly, we do not know exactly what happened during the winter season. We may infer from one sentence in this account that there was some scurvy, readily overcome thanks to the infusion of white cedar; according to some testimonies, the natives kept the settlement in a state of siege and boasted of having killed more than 35 Frenchmen. Cartier struck camp in June 1542.

At the port of St. John’s (Newfoundland) he met Roberval, who had finally put in an appearance with his settlers and who ordered him to turn back. Believing that he was carrying gold and diamonds with him, or not wanting to face the natives again, Cartier headed for France under cover of darkness, thus depriving Roberval of manpower and of precious experience.

Cartier’s fleet was the fleet of illusions: the gold ore was nothing but iron pyrites, and the diamonds were quartz, hence the proverb “as false as Canadian diamonds.” It is not known whether Cartier was reprimanded for his insubordination; in any case he was not given the mission of repatriating Roberval in 1543, and he was not entrusted again with any long-range expedition.

Later Cartier had to sort out his accounts from Roberval’s, and he appeared before a special tribunal in the spring of 1544. He proved that he had been a faithful trustee of the king’s money and of Roberval’s and was repaid about 9,000 livres , although certain merchants claimed in 1588 that the people of Saint-Malo had not yet received what Cartier declared that he had paid them.

In 1545 appeared the Brief récit , an account of the second voyage, published anonymously and mentioning once only in the text the name of Cartier. The navigator is said to have written in this period a “book in the nature of a sea-chart,” but it has not been discovered. He received the Franciscan André Thevet , to whom he gave extensive information about Canada. An hypothesis has been advanced according to which a meeting between Rabelais and the explorer furnished some material for Pantagruel . This hypothesis has received less and less credence, and the last critic to mention it, Bernard G. Hoffman, does not accept it at all.

From this time on, Cartier apparently concentrated upon business and upon the exploitation of his estate of Limoilou. He acted as godfather, or served as a witness at court on various occasions. Cartier was no doubt a man who liked to do himself well; a note in a registry of births, marriages, and deaths associates him with the “hearty tipplers.” The documents of this period usually designate him as a “noble homme,” which places him in the well-established bourgeoisie . He died 1 Sept. 1557, probably at the age of 66 years.

In 1519 he had married Catherine Des Granches, daughter of Jacques Des Granches, chevalier du roi and constable of Saint-Malo; she died in April 1575. They seem to have had no children. It was a nephew, Jacques Noël , who was to try to carry on Cartier’s work.

No authentic portrait of Cartier is known. According to Lanctot, who has made a special study of Cartier’s iconography, eight pictures merit attention: a sketch about two inches high on the so-called Harleian Mappemonde (the latter is attributed to Pierre Desceliers and was made after 1542); a drawing on the Vallard map of 1547; a sketch one inch high in an edition of Ramusio in 1556; a portrait published in 1836 and made by Léopold Massard after the Desceliers sketch; a portrait by François Riss in 1839, reproduced by Théophile Hamel* ; a portrait published by Michelant, taken from a drawing which is said to have belonged to the BN and to have disappeared subsequently; a wooden medallion, 20 in. in diameter, dated 1704 and found in 1908 by Clarke in an old house in Gaspé; and, finally, the copy of a portrait belonging to one of the Marquis de Villefranche. Lanctot is inclined to think that the only authentic one of all these portraits is “the sketch on the Desceliers map,” the others being more or less accurate copies or even fanciful representations.

The accounts of Cartier’s voyages raise a still more awkward problem. The account of the first voyage was published initially in Italian by Ramusio in 1565, then in English by Florio in 1580, and finally in French by Raphaël du Petit-Val in 1598; it is this last text which was used by Marc Lescarbot . A manuscript preserved in the BN (no.841 of the Moreau collection) was edited by the Quebec Literary and Historical Society in 1843, by Michelant and Ramé in 1867, by H. P. Biggar in 1924, by J. Pouliot in 1934, and finally by Th. Beauchesne in 1946. But this manuscript is only a copy of an original which has today disappeared.

The account of the second voyage was published in French as early as 1545, but anonymously. The original manuscript which served for this edition has not been discovered either. Three manuscripts of the account of the second voyage have been preserved in the BN: no.5589, the best one, that published by Lescarbot and thought by Biggar to be the original; no.5644, which is faulty; no.5653, published at Quebec in 1843 and considered by Avezac to be the original. Robert Le Blant maintains in a recent study that none of the three is the original, and that all three are copies of a lost prototype.

Finally, for the account of the third voyage we possess only an incomplete English version compiled by Hakluyt in 1600, from a document which he had found in Paris around 1583 and which is now lost.

The authorship of the accounts is another problem which it has not been possible to resolve. The account of the third voyage, of which we have only the English version, gives us no indication. As for the account of the second voyage, Jehan Poullet has been suggested as the author. He was probably a native of Dol, in Brittany; he was first mentioned 31 March 1535, when he appeared before a meeting in Saint-Malo to submit the roll of the members of the next expedition. His name does not appear on this roll, but it occurs four times in the Brief récit published in 1545. It was in 1888 that Joüon Des Longrais submitted that Poullet, in view of “the obviously exaggerated importance given to him in the Brief Récit ,” must have had a hand in the writing of it, and he added: “Perhaps he is the author.” In 1901 Biggar revived the same argument. Furthermore, perceiving a certain similarity of style between the accounts of the first two voyages, Biggar assumes that Poullet is also the writer of the account of the first voyage. In 1949 another hypothesis was advanced: Marius Barbeau maintained that Rabelais rewrote Cartier’s accounts to present them to the king. Bernard G. Hoffman replied that they in no way recall the style of Rabelais, that the second account must of necessity have been sent to the king not later than 1536, that Rabelais did not know of Cartier’s voyages before 1538, in short that the hypothesis was unfounded.

The problem would be simpler if the original documents could be found, and above all if one knew Cartier better. In Biggar’s view it is obvious that the accounts, such as we know them, were taken from a ship’s log kept by Cartier, and shaped into a literary story. But, argues Biggar, if Cartier could keep a ship’s log, he was incapable of producing a literary story. That Cartier did not have the necessary literary talents has, however, never been demonstrated; to prove that he had not would be as difficult as to prove that he had. For the time being the author of the accounts remains unknown and the problem persists in its entirety.

Cartier has long been hailed by French-speaking historians as the discoverer of Canada. But did Cartier discover Canada? If we understand by that term the Canada of the 16th century, that is to say the region extending from approximately the Île d’Orléans to Portneuf, it is certainly Cartier who discovered it, but in 1535. Canada however has varied in its geographical dimensions: under the French régime it was identical with the settlement of the St. Lawrence, from Gaspé to the Vaudreuil-Soulanges region; the discoverer of this Canada was still Cartier. The same area, transformed in 1763 into the province of Quebec, became the Lower Canada of 1791, and in 1840 was merged with Ontario to form United Canada; up to Confederation the region called Canada still began only at the Gaspé Peninsula. Consequently one can affirm until 1867 that Cartier was the discoverer of Canada; the French-speaking historians were still perfectly correct. But Canada had not finished its development. By the Confederation of 1867 New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were added to it. If Nova Scotia was not reached by John Cabot, it certainly was by the Corte-Reals and by Fagundes; it appears on maps long before Cartier crossed the Atlantic. Finally, since 1949, the year that Newfoundland joined Confederation, the discovery of Canada in its present form must be attributed to the Italian Cabot, who had transferred his allegiance to England.

But even if Cartier’s explorations are not on the same scale as the exploits of Hernando de Soto or of certain South American explorers, he does have a place among the great names of the 16th century. He was the first to make a survey of the coasts of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, to describe the life of the Indians of northeastern North America, and, what is most to his credit, in 1535 he discovered the St. Lawrence River, which was to become the axis of the French empire in America, the vital route which would carry eager explorers towards Hudson Bay, towards the mysterious horizon of the western sea, and towards the Mississippi. Cartier discovered one of the greatest rivers in the world, and he marks the starting-point of France’s occupation of three-quarters of a continent.

Marcel Trudel

The following publications reproduce the various documents relating to Cartier known to date: Biggar, Documents relating to Cartier and Roberval . Hakluyt, Principal navigations (1903–5), VIII, 183–272 (Cartier’s three voyages). Jacques Cartier, Documents nouveaux , éd. F. Joüon Des Longrais (Paris, 1888). Precursors (Biggar). André Thevet, Les singularitez de la France antarctique, autrement nomée Amérique: & de plusieurs terres & isles découvertes de nostre temps (Paris, 1558; autre éd., Anvers, 1558; éd. Paul Gaffarel, Paris, 1878), an account which belongs among these documents.

The principal editions of Cartier’s voyages are as follows: Jacques Cartier, Bref récit; Brief récit & succincte narration . . . (Paris, 1545), reproduced by photostat in Jacques Cartier et la “grosse maladie” (XIX e Congrès international de Physiologie Pub., Montréal, 1953); Voyage de 1534 ; [—— et al .], Voyages de découverte au Canada, entre les années 1534 et 1542, par Jacques Quartier, le sieur de Roberval, Jean Alphonse de Xanctoigne, etc. suivis de la description de Québec et de ses environs en 1608, et de divers extraits relativement au lieu de l’hivernement de Jacques Quartier en 1535–36 (Société littéraire et historique de Québec, 1843). J.-C. Pouliot, La grande aventure de Jacques Cartier: épave bi-centenaire découverte au Cap des Rosiers en 1908 (Québec, 1934). “Voyages de Jacques Cartier au Canada,” éd. Th. Beauchesne, dans Les Français en Amérique (Julien), 77–197. Voyages of Cartier (Biggar). See also J.-E. Roy, Rapport sur les Archives de France relatives à l’histoire du Canada (PAC pub., VI, Ottawa, 1911), 669–72, which summarizes the history of the various mss of Cartier’s voyages and lists the various theories in regard to them.

Of the numerous published studies of Cartier only the most important are given here; certain of them include detailed bibliographies. These studies are listed in chronological order. N.-E. Dionne, Vie et voyages de Jacques Cartier (3 e éd., Québec, 1934) (first published in 1889); Étude archéologique: le fort Jacques Cartier et la Petite Hermine (Montréal, 1891). Biggar, Early trading companies . A.-J.-M. Lefranc, Les navigations de Pantagruel (Paris, 1905). [C.-J.-F. Hénault], “Extrait de la généalogie de la maison Le Veneur . . . ,” NF , VI (1931), 340–43. Marius Barbeau, “Cartier inspired Rabelais,” Can . Geog . J ., IX (1934), 113–25. Lionel Groulx, La découverte du Canada, Jacques Cartier (Montréal, 1934). Gustave Lanctot, Jacques Cartier devant l’histoire (Montréal, 1947); book reviewed by Lionel Groulx, RHAF , I (1947), 291–98. Les voyages de découverte et les premiers établissements (XV e , XVI e siècles) , éd. Ch.-A. Julien, (Colonies et empires, 3 e série, Paris, 1948). Hoffman, Cabot to Cartier , in particular 131–67. Robert Le Blant, “Les écrits attribués à Jacques Cartier,” RHAF , XV (1961–62), 90–103.

For the cartography of Cartier, see Marcel Trudel, Atlas historique du Canada français des origines à 1867 (Québec, 1961), cartes 14–23.

Revisions based on: Arch. et Patrimoine d ’ Ille-et-Vilaine (Rennes, France), “ Recherche documentaire: reg. paroissiaux et état civil , ” Saint-Malo, 1519: archives-en-ligne.ille-et-vilaine.fr/thot_internet/FrmSommaireFrame.asp (consulted 21 May 2014).

General Bibliography

© 1966–2024 University of Toronto/Université Laval

Image Gallery

Document history.

- Published 1966

- Revised 1979

- Sept. 2014, Minor Revision

Occupations and Other Identifiers

Region of birth.

- Europe – France

Region of Activities

- North America – Canada – Quebec – Lower St. Lawrence-Gaspé/North Shore

- North America – Canada – Quebec – Montréal/Outaouais

- North America – Canada – Quebec – Québec

- North America – Canada – Quebec – Trois-Rivières/Eastern Townships

- North America – Canada – Newfoundland and Labrador – Newfoundland

Related Biographies

VERRAZZANO, GIOVANNI DA

CABOT, JOHN

CORTE-REAL, GASPAR

LA ROCQUE DE ROBERVAL, JEAN-FRANÇOIS DE

THEVET, ANDRÉ

HAMEL, THÉOPHILE

LESCARBOT, MARC

FAGUNDES, JOÃO ALVARES

CHAMPLAIN, SAMUEL DE

MEMBERTOU (baptized Henri)

GAULTIER DE VARENNES ET DE LA VÉRENDRYE, PIERRE (Boumois)

FARIBAULT, GEORGES-BARTHÉLEMI

FERLAND, JEAN-BAPTISTE-ANTOINE

GARNEAU, FRANÇOIS-XAVIER

CARTIER, Sir GEORGE-ÉTIENNE

CHAUVEAU, PIERRE-JOSEPH-OLIVIER

DAWSON, Sir JOHN WILLIAM

HALE, HORATIO EMMONS

HOWLEY, MICHAEL FRANCIS

PROWSE, DANIEL WOODLEY

TACHÉ, EUGÈNE-ÉTIENNE

MACHAR, AGNES MAULE

PROUVILLE DE TRACY, ALEXANDRE DE

SNORRI THORFINNSSON

HAMEL, EUGÈNE (baptized Joseph-Eugène-Arthur)

Cite This Article

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the chicago manual of style (16th edition). information to be used in other citation formats:.

- Kindergarten

- Middle School

- High School

- Math Worksheets

- Language Arts

- Social Studies

More Topics

- Handwriting

- Difference Between

- 2020 Calendar

- Online Calculators

- Multiplication

Educational Videos

- Coloring Pages

- Privacy policy

- Terms of Use

© 2005-2020 Softschools.com

Second Voyage of Jaques Cartier

Jacques Cartier's second voyage to the New World commenced on May 19, 1535, a little more than a year after his return from his initial expedition. This time, Cartier commanded a flotilla of three ships—the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine, and the Émérillon—with a crew totaling around 110 men. His main objective remained the same: to find a westward route to Asia that would allow France to participate in the lucrative spice trade.

Setting sail from St. Malo, France, Cartier and his fleet made their way across the Atlantic Ocean, guided by two Iroquois sons of Chief Donnacona, Domagaya and Taignoagny, who had returned from France for this expedition. Arriving in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Cartier followed the St. Lawrence River, a waterway he hoped would serve as a route to Asia. Instead, the river led him deep into the North American continent.