In the 21st century, it is commonplace to travel by plane—and many Americans are familiar with the flying experience—but this wasn't always the case.

In the early days of commercial flight, the flying experience was harsh and uncomfortable. To even get the opportunity to fly was considered a luxury. Learn more about the evolution of the commercial flying experience in the United States using objects from the Museum's collection.

Jump to: 1914-1927 1927-1941 1941-1958 1958-Today

Novel and exciting; loud and uncomfortable—an experience few people ever got to relish or regret.

In the early years of flight, pilots and the occasional passenger sat in open cockpits exposed to wind and weather. Even in Europe, where large transports carried passengers in comparative luxury, the ride was harsh, loud, and uncomfortable.

Mostly pilots. Most early airplanes could carry only a single extra person, if any. Few passenger-carrying airlines existed, and none survived for very long. Those that did catered to wealthy travelers who could afford the expensive ticket prices. In this period, most airlines made their money by flying the mail for the federal government. Except for the occasional hop in the spare seat of a stunt preforming Curtiss Jenny for a joy ride, few Americans flew as passengers in planes, and even fewer used them as a means to travel.

Joseph L. Mortensen navigated the air mail route from Salt Lake City, Utah, to Reno, Nevada, in 1920 using this scrolling map and knee board. This object is called a "knee board" because a pilot would strap it to their leg. They would turn the knobs to scroll the map as they flew their route.

Why would this be more useful than a folding map?

Lt. James Edgerton flew the mail from Philadelphia to Washington during the first scheduled air mail flight on May 15, 1918. He wore this helmet and coat during that flight. Edgerton left the Army in 1919 and became the Chief of Flying for the U.S. Air Mail Service.

This is Lt. James Edgerton's logbook, with entries for May 14 and 15, 1918. Pilots wrote down their experiences so other pilots could learn from them. What problems did Edgerton have? How long did it take him to fly from Bustleton Field to Washington?

On May 15, 1918, Lt. Howard P. Culver navigated between Philadelphia and Belmont Park, near New York City, during the first scheduled air mail flight, using this liquid-filled compass installed in his Curtiss Jenny.

This letter was carried on the first scheduled air mail flight. What does the letter predict will happen in the future of travel by plane?

More About Air Mail

Despite the airlines' cheerful advertising, early air travel continued to be far from comfortable. It was expensive too.

Flying was loud, cold, and unsettling. Airliners were not pressurized, so they flew at low altitudes and were often bounced about by wind and weather. Air sickness was common. Airlines provided many amenities to ease passenger stress, but air travel remained a rigorous adventure well into the 1940s.

Flying was very expensive. Only business travelers and the wealthy could afford to fly. Most people still rode trains or buses for intercity travel because flying was so expensive. A coast-to-coast round trip cost around $260, about half of the price of a new automobile. But despite the expense and discomforts, each year commercial aviation attracted thousands of new passengers willing to sample the advantages and adventure of flight. America's airline industry expanded rapidly, from carrying only 6,000 passengers in 1929 to more than 450,000 by 1934, to 1.2 million by 1938. Still, only a tiny fraction of the traveling public flew.

Noise was a problem in early airliners. To communicate with passengers, cabin crew often had to resort to speaking through small megaphones to be heard above the din of the engines and the wind. The noise in a typical Ford Tri-Motor during takeoff was nearly 120 decibels, loud enough to cause permanent hearing loss.

How Noisy Was It?

- Normal conversation: 60 dB

- Busy street traffic: 70 dB

- Vacuum cleaner: 80 dB

- Front rows of rock concert: 110 dB

- Ford Tri-Motor during takeoff: 120 dB

- Threshold of pain: 130 dB

- Instant perforation of eardrum: 160 dB

"There is still a newness about air travel, and, though statistics demonstrate its safety, the psychological effect of having a girl on board is enormous." -Comment about the addition of stewardesses from an airline magazine, 1935

The first stewardess uniform was made of dark green wool with a matching green and gray wool cape. United Air Lines made this replica and donated it in commemoration of Ellen Church, the first stewardess, and the rest of United's

A nurse from Iowa, Ellen Church wanted to become an airline pilot but realized that was not possible for a woman in her day. So in 1930, she approached Steve Simpson at Boeing Air Transport with the novel idea of placing nurses aboard airliners. She convinced him that the presence of women nurses would help relieve the traveling public's fear of flying. The addition of female flight attendants fundamentally changed the flying experience—sometimes to the detriment of the female flight attendants themselves—and would continue to shape it for years to come.

View Uniform

Learn More About Flight Attendants

Passengers on T.W.A.'s Douglas DC-2s were given overnight flight bags for transcontinental flights.

American issued this overnight flight bag to passengers flying on its Curtiss Condors and later on its Douglas Sleeper Transports.

To ease pressure on passengers' ears during climb and descent, stewards on Eastern Air Lines flights in the late 1930s offered chewing gum from elegant polished steel dispensers.

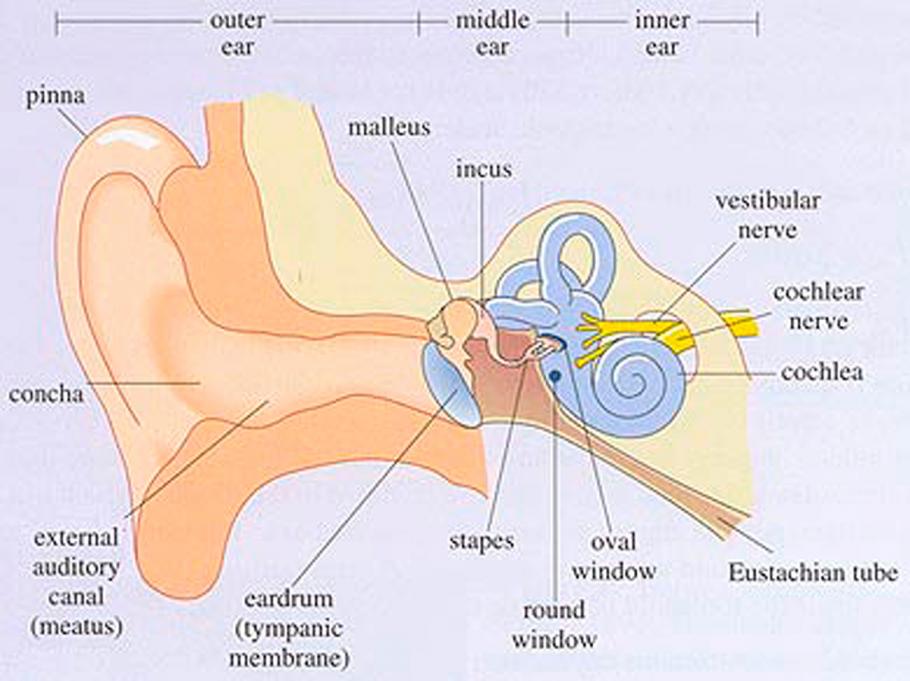

Why do your ears hurt?

Your ears pop during takeoff and landing because of tiny tubes, full of air, that connect your ears to your throat. Air pressure changes during ascent and descent cause pressure differences within your head, and those tubes become blocked. When you yawn or swallow, you open the tubes and equalize the pressure. Chewing gum helps you generate saliva to swallow, but you don't really need the gum at all!

Your ears pop during takeoff and landing because of tiny tubes, full of air, that connect your ears to your throat. Air pressure changes during ascent and descent cause pressure differences within your head, and those tubes become blocked. When you yawn or swallow, you open the tubes and equalize the pressure. Chewing gum helps you generate saliva to swallow, but you don't really need the gum at all!

In 1955, for the first time, more people in the United States traveled by air than by train. By 1957 airliners had replaced ocean liners as the preferred means of crossing the Atlantic.

After World War II, passenger travel surged to new levels. When wartime travel restrictions ended, airlines were overwhelmed with passengers. New carriers emerged, and new technology began to revolutionize civil aviation.

The era of mass air travel had begun—for some. African Americans could choose to fly, but few did. Many airport facilities were segregated and discrimination was widespread. While the airlines were not legally segregated, airports often were. Throughout the South, inferior airport accommodations discouraged African Americans from flying. Until the Civil Rights movement began to bring about change, air travel remained mostly for white people.

Learn More About Air Travel and Segregation

Since the federal government regulated prices, airlines competed by offering various amenities. Whether United's "red carpet service," for which a brochure can be seen here, or American's "service fit for a king and queen," airline advertising made sure passengers knew they would be treated well. As one American Airlines publication noted, "travel by air should be a time of leisure, a chance for you to escape humdrum worries."

View Brochure from Continental

Matchbooks like this one were provided to passengers interested in smoking during their flight. According to one brochure, cigar and pipe smoking were "permitted in the lounge of DC-6Bs only!"

Airlines provided junior pilot wings link these to children, just one of the amenities for families.

Airlines provided junior stewardess wings like these to children, just one of the amenities for families.

United Air Lines menu for a gourmet in flight meal.

Jet Lag Before Jets

Passengers began experiencing physiological problems due to crossing several time zones within a few hours. Shortened or lengthened days or nights upset natural body rhythms and made sleeping difficult. Although later dubbed "jet lag," this was first experienced after long-distance trips on fast piston-engine and turboprop airliners.

As flying became more popular and commonplace, the nature of the air travel experience began to change. By the end of the 1950s, America's airlines were bringing a new level of speed, comfort, and efficiency to the traveling public. However, with the steady increase in passenger traffic, the level of personal service decreased. The stresses of air travel began to replace the thrill. Flying was no longer a novelty or an adventure; it was becoming a necessity.

Jet passenger service began in the United States in the late 1950s with the introduction of Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8 airliners.

Some 707 flights were all-first class, others all tourist class, and others a mix separated by partitions.

The jet engine revolutionized air travel. Powerful and durable, jets enabled aircraft manufacturers to build bigger, faster, and more productive airliners. The effects of deregulation, along with the computer revolution and heightened security measures, especially following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, have profoundly changed the nature of the air travel experience.

"Jetting" across the Atlantic briefly became highly fashionable and prestigious, and a new breed of travelers— the "Jet Set"— emerged. But falling fares in the 1970s allowed many more people to fly and undermined the exclusivity of jet travel.

Sweeping cultural changes in the 1960s and 1970s reshaped the airline industry. More people began to fly, and air travel became less exclusive. Between 1955 and 1972, passenger numbers more than quadrupled. By 1972 almost half of all Americans had flown, although most passengers were still business travelers. A small percentage became repeat travelers, or "frequent flyers."

Today, airline travel is the safest form of transportation. More people die in auto accidents in three months in the United States than have lost their lives in the entire history of commercial flight. It is far safer to fly than it is to get to the airport.

Because air travel is so safe and accidents so rare, when an incident occurs it is often highly publicized, which heightens the unwarranted perception of danger.

Since the advent of high-altitude pressurized airliners in the early 1940s, airliners have featured oxygen masks such as this one, as well as evacuation slides and rafts to aid passengers and crew in emergencies.

View Boarding Pass Examples

Since deregulation, travelers have benefited from low fares and more frequent service on heavily traveled routes; on other routes, fares have risen. But in exchange for low fares, passengers have had to sacrifice convenience and amenities. To offer low air fares, airlines have had to cut costs in other ways, often by reducing, eliminating, or charging for amenities that air travelers once took for granted.

Computer technology, in particular the Internet, has revolutionized how people plan trips, buy tickets, and obtain boarding passes. Heightened security, especially since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, has made the airport experience more restrictive and time-consuming.

Hundreds of millions of passengers now fly each year in the United States. But that popularity has also brought crowded airplanes and congested airports and has dulled the luster air travel once had.

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

History of Flight: Breakthroughs, Disasters and More

By: Aaron Randle

Updated: February 6, 2024 | Original: July 9, 2021

For thousands of years, humans have dreamed of taking to the skies. The quest has led from kite flying in ancient China to hydrogen-powered hot-air balloons in 18th-century France to contemporary aircraft so sophisticated they can’t be detected by radar or the human eye.

Below is a timeline of humans’ obsession with flight, from da Vinci to drones. Fasten your seatbelt and prepare for liftoff.

1505-06: Da Vinci dreams of flight, publishes his findings

Few figures in history had more detailed ideas, theories and imaginings on aviation as the Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci . His book Codex on the Flight of Birds contained thousands of notes and hundreds of sketches on the nature of flight and aerodynamic principles that would lay much of the early groundwork for—and greatly influence—the development of aviation and manmade aircraft.

November 21, 1783: First manned hot-air balloon flight

Two months after French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier engineered a successful test flight with a duck, a sheep and a rooster as passengers, two humans ascended in a Montgolfier-designed balloon over Paris. Powered by a hand-fed fire, the paper-and-silk aircraft rose 500 vertical feet and traveled some 5.5 miles over about half an hour. But in an 18th-century version of the space race, rival balloon engineers Jacques Alexander Charles and Nicholas Louis Robert upped the ante just 10 days later. Their balloon, powered by hydrogen gas, traveled 25 miles and stayed aloft more than two hours.

1809-1810: Sir George Cayley introduces aerodynamics

At the dawn of the 19th century, English philosopher George Cayley published “ On Aerial Navigation ,” a radical series of papers credited with introducing the world to the study of aerodynamics. By that time, the man who came to be known as “the father of aviation” had already been the first to identify the four forces of flight (weight, lift, drag, thrust), developed the first concept of a fixed-wing flying machine and designed the first glider reported to have carried a human aloft.

September 24, 1852: Giffard's dirigible proves powered air travel is possible

Half a century before the Wright brothers took to the skies, French engineer Henri Giffard manned the first-ever powered and controllable airborne flight. Giffard, who invented the steam injector, traveled almost 17 miles from Paris to Élancourt in his “Giffard Dirigible,” a 143-foot-long, cigar-shaped airship loosely steered by a three-bladed propeller that was powered by a 250-pound, 3-horsepower engine, itself lit by a 100-pound boiler. The flight proved that a steam-powered airship could be steered and controlled.

1876: The internal combustion engine changes everything

Building on advances by French engineers, German engineer Nikolaus Otto devised a lighter, more efficient, gas-powered combustion engine, providing an alternative to the previously universal steam-powered engine. In addition to revolutionizing automobile travel, the innovation ushered in a new era of longer, more controlled aviation.

December 17, 1903: The Wright brothers become airborne—briefly

Flying from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first controlled, sustained flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft. Each brother flew their wooden, gasoline-powered propeller biplane, the “Wright Flyer,” twice (four flights total), with the shortest lasting 12 seconds and the longest sustaining flight for about 59 seconds. Considered a historic event today, the feat was largely ignored by newspapers of the time, who believed the flights were too short to be important.

1907: The first helicopter lifts off

French engineer and bicycle maker Paul Cornu became the first man to ride a rotary-wing, vertical-lift aircraft, a precursor to today’s helicopter, when he was lifted about 1.5 meters off the ground for 20 seconds near Lisieux, France. Versions of the helicopter had been toyed with in the past—Italian engineer Enrico Forlanini debuted the first rotorcraft three decades prior in 1877. And it would be improved upon in the future, with American designer Igor Sikorsky introducing a more standardized version in Stratford, Connecticut in 1939. But it was Cornu’s short flight that would land him in the history books as the definitive first.

1911-12: Harriet Quimby achieves two firsts for women pilots

Journalist Harriet Quimby became the first American woman ever awarded a pilot’s license in 1911, after just four months of flight lessons. Capitalizing on her charisma and showmanship (she became as famous for her violet satin flying suit as for her attention to safety checks), Quimby achieved another first the following year when she became the first woman to fly solo across the English channel. The feat was overshadowed, however, by the sinking of the Titanic two days earlier.

October 1911: The aircraft becomes militarized

Italy became the first country to significantly incorporate aircraft into military operations when, during the Turkish-Italian war, it employed both monoplanes and airships for bombing, reconnaissance and transportation. Within a few years, aircraft would play a decisive role in the World War I.

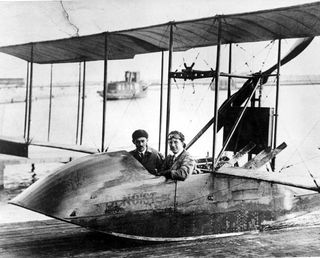

January 1, 1914: First commercial passenger flight

On New Year’s Day, pilot Tony Jannus transported a single passenger, Mayor Abe Pheil of St. Petersburg, Florida across Tampa Bay via his flying airboat, the “St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line.” The 23-mile flight (mostly along the Tampa Bay shore) cost $5.00 and would lay the foundation for the commercial airline industry.

1914-1918: World war accelerates the militarization of aircraft

World War I became the first major conflict to use aircraft on a large-scale, expanding their use in active combat. Nations appointed high-ranking generals to oversee air strategy, and a new breed of war hero emerged: the fighter pilot or “flying ace.”

According to The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft , France was the war’s leading aircraft manufacturer, producing nearly 68,000 planes between 1914 and 1918. Of those, nearly 53,000 were shot down, crashed or damaged.

June 1919: First nonstop transatlantic flight

Flying a modified ‘Vickers Vimy’ bomber from the Great War, British aviators and war veterans John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first-ever nonstop transatlantic flight. Their perilous 16-hour journey , undertaken eight years before Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic alone, started in St. John's, Newfoundland, where they barely cleared the trees at the end of the runway. After a calamity-filled flight, they crash-landed in a peat bog in County Galway, Ireland; remarkably, neither man was injured.

1921: Bessie Coleman becomes the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license

The fact that Jim Crow-era U.S. flight schools wouldn’t accept a Black woman didn’t stop Bessie Coleman. Instead, the Texas-born sharecropper’s daughter, one of 13 siblings, learned French so she could apply to the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. There, in 1921, she became the first African American woman to earn a pilot's license. After performing the first public flight by a Black woman in 1922—including her soon-to-be trademark loop-the-loop and figure-8 aerial maneuvers—she became renowned for her thrilling daredevil air shows and for using her growing fame to encourage Black Americans to pursue flying. Coleman died tragically in 1926, as a passenger in a routine test flight. Thousands reportedly attended her funeral in Chicago.

1927: Lucky Lindy makes first solo transatlantic flight

Nearly a decade after Alcock and Brown made their transatlantic flight together, 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh of Detroit was thrust into worldwide fame when he completed the first solo crossing , just a few days after a pair of celebrated French aviators perished in their own attempt. Flying the “Spirit of St. Louis” aircraft from New York to Paris, “Lucky Lindy” made the first transatlantic voyage between two major hubs—and the longest transatlantic flight by more than 2,000 miles. The feat instantly made Lindbergh one of the great folk heroes of his time, earned him the Medal of Honor and helped usher in a new era of interest in the possibilities of aviation.

1932: Amelia Earhart repeats Lindbergh’s feat

Five years after Lindbergh completed his flight, “Lady Lindy” Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean , setting off from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland on May 20, 1932 and landing some 14 hours later in Culmore, Northern Ireland. In her career as an aviator, Earhart would become a worldwide celebrity, setting several women’s speed, domestic distance and transcontinental aviation records. Her most memorable feat, however, would prove to be her last. In 1937, while attempting to circumnavigate the globe, Earhart disappeared over the central Pacific ocean and was never seen or heard from again.

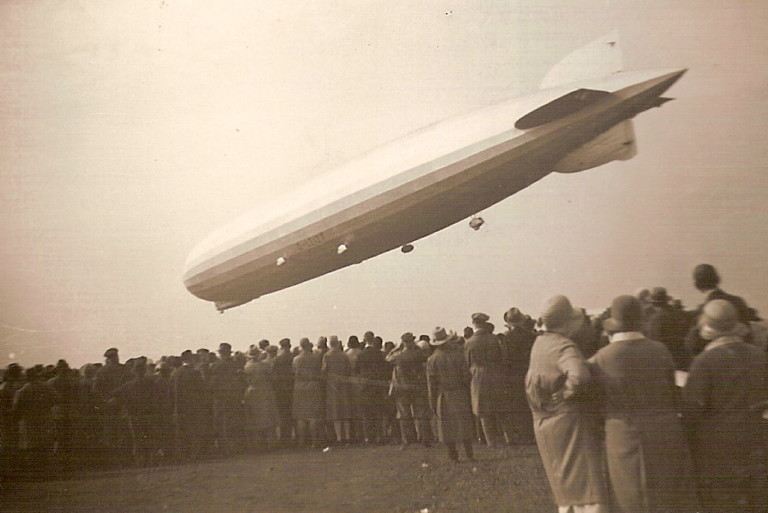

1937: The Hindenburg crashes…along with the ‘Age of Airships’

Between WWI and WWII, aviation pioneers and major aircraft companies like Germany’s Luftshiffbau Zeppelin tried hard to popularize bulbous, lighter-than-air airships—essentially giant flying gas bags—as a mode of commercial transportation. The promise of the steam-powered, hydrogen-filled airships quickly evaporated, however, after the infamous 1937 Hindenburg disaster . That’s when the gas inside the Zeppelin company’s flagship Hindenburg vessel exploded during a landing attempt, killing 35 passengers and crew members and badly burning the majority of the 62 remaining survivors.

October 14, 1947: Chuck Yeager breaks the sound barrier

An ace combat fighter during WWII, Chuck Yeager earned the title “Fastest Man Alive” when he hit 700 m.p.h. while testing the experimental X-1 supersonic rocket jet for the military over the Mojave Desert in 1947. Being the first person to travel faster than the speed of sound has been hailed as one of the most epic feats in the history of aviation—not bad for someone who got sick to his stomach after his first-ever flight.

1949: The world’s first commercial jetliner takes off

Early passenger air travel was noisy, cold, uncomfortable and bumpy, as planes flew at low altitudes that brought them through, not above, the weather. But when the British-manufactured de Havilland Comet took its first flight in 1949—boasting four turbine engines, a pressurized cabin, large windows and a relatively comfortable seating area—it marked a pivotal step in modern commercial air travel. An early, flawed design however, caused the de Havilland to be grounded after a series of mid-flight disasters—but not before giving the world a glimpse of what was possible.

1954-1957: Boeing glamorizes flying

With the debut of the sleek 707 aircraft, touted for its comfort, speed and safety, Seattle-based Boeing ushered in the age of modern American jet travel. Pan American Airways became the first commercial carrier to take delivery of the elongated, swept-wing planes, launching daily flights from New York to Paris. The 707 quickly became a symbol of postwar modernity—a time when air travel would become commonplace, people dressed up to fly and flight attendants reflected the epitome of chic. The plane even inspired Frank Sinatra’s hit song “Come Fly With Me.”

March 27, 1977: Disaster at Tenerife

In the greatest aviation disaster in history, 583 people were killed and dozens more injured when two Boeing 747 jets—Pan Am 1736 and KLM 4805— collided on the Los Rodeos Airport runway in Spain’s Canary Islands. The collision occurred when the KLM jet, trying to navigate a runway shrouded in fog, initiated its takeoff run while the Pan Am jetliner was still on the runway. All aboard the KLM flight and most on the Pan Am flight were killed. Tragically, neither plane was scheduled to fly from that airport on that day, but a small bomb set off at a nearby airport caused them both to be diverted to Los Rodeos.

1978: Flight goes electronic

The U.S. Air Force developed and debuted the first fly-by-wire operating system for its F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter plane. The system, which replaced the aircraft’s manual flight control system with an electronic one, ushered in aviation’s “Information Age,” one in which navigation, communications and hundreds of other operating systems are automated with computers. This advance has led to developments like unmanned aerial vehicles and drones, more nimble missiles and the proliferation of stealth aircraft.

1986: Around the world, without landing

American pilots Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck) completed the first around-the-world flight without refueling or landing . Their “Rutan Model 76 Voyager,” a single-wing, twin-engine craft designed by Rutan’s brother, was built with 17 fuel tanks to accommodate long-distance flight.

HISTORY Vault: 101 Inventions That Changed the World

Take a closer look at the inventions that have transformed our lives far beyond our homes (the steam engine), our planet (the telescope), and our wildest dreams (the Internet).

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The world's first commercial airline

The first commercial flight shortened travel time by more than 90 minutes.

Launching the first commercial airline

The first commercial airline pilot, flying boats, the first commercial flight, many more passengers, additional resources, bibliography.

On Jan. 1, 1914, the world's first scheduled passenger airline service took off from St. Petersburg, FL and landed at its destination in Tampa, FL, about 17 miles (27 kilometers) away. The St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line was a short-lived endeavor — only four months — but it paved the way for today's daily transcontinental flights.

The first flight's pilot was Tony Jannus, an experienced test pilot and barnstormer, according to the International Air Transport Association . The first paying passenger was Abram C. Pheil, former mayor of St. Petersburg. Their short flight across the bay to Tampa took 23 minutes. They flew in a "flying boat" designed by Thomas Benoist , an aviation entrepreneur from St. Louis, according to the State Historical Society of Missouri .

Percival Elliott Fansler, a Florida sales representative for a manufacturer of diesel engines for boats, became fascinated with Benoist's progress in designing aircraft that could take off and land in the water. The two men started corresponding, and eventually Fansler proposed "a real commercial line from somewhere to somewhere else," according to Tampapix.com , a web-based amateur historical archive about Tampa.

Fansler proposed that the airline fly between St. Petersburg and Tampa. At that time, a trip between the two cities, sitting on opposite sides of Tampa Bay, took two hours by steamship or up to 12 hours by rail. Traveling by automobile around the bay took about 20 hours. But a flight would take about 20 minutes.

Fansler tried to interest Tampa officials in the venture, but they turned him down. He got a better reception in St. Petersburg, enticing several investors. Benoist arrived in St. Petersburg on Dec. 12, 1913, followed by his hand-picked pilot, Tony Jannus.

Jannus was already a popular figure in aviation. He was rather debonair and his daredevil flights led him to become "the epitome of the romantic flyer." The Tony Jannus Distinguished Aviation Society describes Jannus as someone "known as a fearless daredevil and admirer of women, running from angry fathers with pointed shotguns and dating movie stars, Jannus took risks in love and war."

Jannus gave flying exhibitions, tested military planes and flew long-distance airplanes and airboats. He piloted the first tests of airborne machine guns. On March 1, 1912, he carried Capt. Albert Berry aloft to make the first parachute jump from an airplane. Then by 1913, at age 24, he had become one of the principal stockholders in the Benoist Aircraft Company.

A Model 14 Benoist airboat was shipped to St. Petersburg by train. It weighed 1,250 lbs. (567 kilograms), was 26 feet (8 meters) long and had a wingspan of 44 feet (13 m). It was powered by a Roberts 6-cylinder, in-line, liquid-cooled, 75-horsepower engine. The airplane had a top speed of 64 mph (103 km/h). The hull was made of three layers of spruce with fabric between each layer. The wings were made of spruce spars with linen stretched over them. The plane was built to hold only a pilot and one passenger side-by-side on a single wooden seat.

The first flight went off on New Year's Day, 1914, with much pomp and circumstance. An estimated 2,000 people paraded from downtown St. Petersburg to the waterfront to watch as the first ticket was auctioned off. Pheil, then in the warehouse business, won with a bid of $400 (a value equal to more than $11,200 today).

Just before the flight, Fansler made a brief speech, saying, “What was impossible yesterday is an accomplishment today, while tomorrow heralds the unbelievable,” the Tampa Bay Times reported. After several more speeches and many photographs, Jannus and Pheil squeezed onto the small wooden seat. As they took off, Jannus waved to the cheering crowd.

He flew the plane no higher than 50 ft (15.2 m) over the water. Halfway to Tampa, the engine misfired, and he touched down in the bay, made adjustments and took off again. As the plane landed at the entrance of the Hillsborough River near downtown Tampa, Jannus and Pheil were swarmed by a cheering, clapping, and waving crowd of about 3,500.

Pheil went about his business and placed an order of several thousand dollars for his wholesale company. At 11 a.m., Jannus and Pheil flew back to St. Petersburg. The entire trip had taken less than an hour and a half.

The airline made two flights daily, six days a week. The regular fare was $5 per person (about $140 in today's dollars) and $5 per 100 pounds of freight. Tickets sold out for 16 weeks in advance. Benoist added a second airboat and flights were extended to the nearby cities of Sarasota, Bradenton and Manatee. Tony Jannus' brother, Roger, was the second pilot.

The airline operated for nearly four months, and carried a total of 1,205 passengers. Passenger interest declined rapidly when Florida's winter residents began heading back north in late March. On April 27, Tony and Roger Jannus flew their last flight before leaving Florida, putting on an air show over Tampa Bay.

The brothers continued to give exhibitions, perform tests of aircraft, and train other pilots. On Oct. 12, 1916, Tony Jannus was training Russian pilots when his plane crashed into the Black Sea. His body was never recovered.

Roger Jannus also died while flying. He crashed on Sept. 4, 1918, during air patrols over France.

In 1964, the Tampa and St. Petersburg Chambers of Commerce established the Tony Jannus Distinguished Aviation Society in honor of Tony Jannus.

There are numerous books delving into the secrets of today's commercial airlines. But for a thorough read that focuses on the history of commercial flight, consider T. A. Heppenheimer's " Turbulent Skies: The History of Commercial Aviation " (Wiley, 1995). For an easy-to-read historical guide to planes with illustrations, we recommend H. Barber's " The Aeroplane Speaks " (CGR Publishing, 2020), originally published in 1917. Michael Coscia's " Wings Over America: The Fact-Filled Guide to the Major and Regional Airlines of the U.S.A " (Bluewater Press, 2009).

- IATA 2022. "The story of the world's first airline." https://www.iata.org/en/about/history/flying-100-years/firstairline-story/

- Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. "The World's First Scheduled Airline" https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/america-by-air/online/early_years/early_years01.cfm

- First Flight Society. "Tony Jannus." https://firstflight.org/tony-jannus/

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- Kimberly Hickok Contributing Writer

SpaceX launching Falcon 9 rocket on record-tying 20th mission today

Boeing's Starliner spacecraft is 'go' for May 6 astronaut launch

Russia vetoes UN resolution against nuclear weapons in space

Most Popular

- 2 Beavers are helping fight climate change, satellite data shows

- 3 Astronomers just discovered a comet that could be brighter than most stars when we see it next year. Or will it?

- 4 This Week In Space podcast: Episode 108 — Starliner: Better Late Than Never?

- 5 Boeing's Starliner spacecraft will not fly private missions yet, officials say

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

In flight: see the planes in the sky right now

To mark 100 years of passenger air travel, our stunning interactive uses live data from FlightStats to show every one of the thousands of commercial planes currently in the air, charts the history of aviation since 1914, and asks what comes next for the industry

- Travel and transport

Heathrow and Gatwick shortlisted for new runway as airport options unveiled

Whether or not it's Heathrow, airport expansion is just another glamorous project for the rich

When it comes to airports, small is beautiful

Most viewed.

Birth of Aviation

The history of commercial aviation, the birth of commercial aviation.

Commercial aviation has changed the world immeasurably, facilitating world trade and economic growth, bringing people together in a way that was not possible before, and simply making the world a more connected place. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), airlines in 2014 connected 3.3 billion people and 52 million tonnes of cargo over 50,000 routes, supporting 58 million jobs and delivering goods with a value of $6.8 trillion [ 1 ] . But when and where does commercial aviation find its inception?

COMMERCIAL AVIATION HISTORY

From the earliest beginnings, man’s ascent to flight has been one of gradual progress, accented by a handful of dramatic breakthroughs. The Wright Brother’s accomplishment would of course be one such breakthrough. Though several others can claim successful efforts at manned, powered flight prior to Kitty Hawk (see article, “First Human Flying Machines” ), the Wright Brothers hold a special place in history because of the profound and lasting impact of their achievement in relation to modern aircraft design (three-axis control).

Similarly, in the history of commercial aviation there is evidence of gradual evolution – from stunt plane and site seeing passenger flights to flying airboats that flew just a few feet above the water to the first real examples of modern air travel involving regularly-scheduled overland air service using land-based runways. And there are a few critical breakthroughs as well that would play a important role in the birth of a new industry. One of those breakthroughs was spurred on by a group of individuals in the mid-1920s led by the Guggenheims – a family who amassed a great fortune in the mining industry, and then turned their focus towards giving back to society. Together, they shared the vision of making passenger airtravel a sustainable reality, along with the spirit of boldness to make it happen. The elder Daniel Guggenheim would say of aviation at a 1925 groundbreaking ceremony for construction of the nation’s first school of aeronautics at a major American college, “I consider it the greatest road to opportunity which lies before the science and commerce of the civilized countries of the earth today.” [ 2 ]

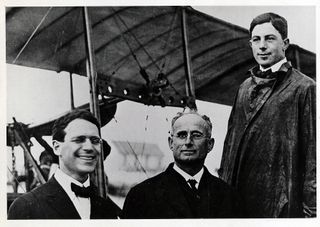

Harry Guggenheim and Charles Lindberg leaving New Western Air Express plane in 1928. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

Western Air Express pilot Jimmy James. [see page for license], via Wikimedia Commons

As such, when Western Airlines became part of Delta in 1986, Delta inherited bragging rights to the oldest ticket sold for passenger airtravel. No U.S. airliner in operation today can say it issued a ticket prior to the one sold in 1926 to Mr Ben Redman of Salt Lake City, Utah.

THE FIRST PASSENGERS

When Western Air Express pilot C.N. “Jimmy” James took off on his regular eight-hour mail delivery flight from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles on May 23, 1926 – almost exactly one year prior to the famous transatlantic flight of Charles Lindberg – he would do so carrying what was proudly referred to by Western Airlines CEO Arthur Kelly in 1961 as the “first commercial airline passenger”. [ 15 ] The recipient of this honor would be then president of the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce Ben F. Redman who, along with his friend (and second passenger) J.A. Tomlinson, sat atop U.S. mail sacks, sported his own parachutes, and relied on a tin cup for the in-flight lavatory.

Source: “Western Airlines Marks Anniversary of S.L. Flight”, Salt Lake City Tribune , April 17, 1944, p.16

Later, Redman and James would appear with Elliot Roosevelt, son of President Roosevelt, as Elliot would receive the honor of being the 100,000th passenger flying from Los Angeles via Western Air Express on that same route. (See below)

Source: “Elliott Roosevelt Inspects Airlines”, Salt Lake City Tribune , September 25, 1933, p.22.

“They took off at 9:30am and five hours later landed at Las Vegas to refuel. Redman and Tomlinson staggered out of the plane to stretch their legs and would have been forgiven if they had refused to reboard; for a good portion of the trip they had flown through a dust storm, and both passengers were pale from fatigue and nervousness. But they also were game, and three hours later climbed more or less jauntily out of the M-2, waving to the crowd of photographers and reporters gathered at Vail Field to record the arrival.” [ 16 ]

Upon completion of the inaugural flight, a certificate signed by the pilot Jimmy James was presented. The certificate (shown below) confirms Redman as the first official passenger , as well as recording details of the flight including maximum altitude reached (12,000 feet), the maximum speed (130 mph), total flying time (8 hours), and Contract Air Mail Route (No. 4).

Certificate confirming Mr. Ben Redman of Salt Lake City, Utah as the first official passenger to fly on Western Air Express. This was presented in a ceremony after WAE’s inauguration of passenger service on May 23, 1926, which represented the first “regularly scheduled passenger flight” in the United States. Part of the BirthofAviation.org Collection. ( see preferred citation )

FIRST TRUE SUCCESS STORY IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION

Perhaps most significant of all regarding Western Air Express’s inauguration of passenger service is that it marked the beginning of the first true success story in U.S. commercial aviation. For as mentioned there were a few early airboat ventures that did sell tickets for airtravel prior to 1926. Yet they would all end in bankruptcy, most going out of business shortly after their inception (see First U.S. Passenger Airlines ). The February 1976 edition of The Vintage Airplane thus declared, “Western Air Lines is the only survivor of airlines that pioneered commercial air transportation in the U.S. in the mid-twenties.” [ 17 ]

Vintage Art Poster shows a Western Air Express plane flying over the location where the Golden Gate Bridge now stands.

Helped by the Guggenheim grant, along with the infrasture and other innovations spawned by the model airline experiment over the next few years, Western would not only avoid bankruptcy but would go on to become an industry giant. After surprising many by posting a profit of $28,674.19 in its first year of operation, [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Western Air Express would the following year, in 1927, become the first airline in history to pay a cash dividend to its stockholders. [ 20 ] In 1928, it would post a profit of approximately $700,000. [ 21 ] And by 1930 it had become the largest airline in the nation by most overall standards of measurement – including fleet size, passengers carried, and route mileage with routes stretching 15,832 miles. [ 22 ] (That same year it would also introduce to the world of commercial aviation what was at the time by far the largest passenger plane in the world, the four-engined 32-passenger Fokker F-32, as shown below). [ 23 ]

Of course, the Guggenheim fund that helped fuel this success was never intended to provide an economic advantage to any one airline in particular, but rather to buoy the entire industry – and that is indeed what it did. The success of the model airline experiment would not only benefit Western but would in effect usher in the beginning of sustainable economic progress for all U.S. airliners through a number of key innovations.

One innovation of lasting impact achieved by the model airline would be the first weather reporting for passenger airplanes. In August 1927, the Daniel Guggenheim Committee on Aeronautical Meteorology was created to make pilots and meteorologists aware of each other’s specialties. The five-person committee, all of whom would achieve prominence in meteorology and two of whom would become chiefs of the Weather Bureau, recommended that the Guggenheim Fund equip a section of the airway system with weather reporting systems to prove the feasibility of such a system. Ultimately, it was decided to carry this out along the Western Air Express model air line route, resulting in an initial twenty-two reporting stations connected via telephone to Los Angeles and San Francisco, and soon later more would be added. These would serve all airmen, not just those of Western Air Express.

This project, involving collaboration from the Department of Commerce and the Weather Bureau, as well as the army, would add great benefit not only in economy of operation but also in safety. Lt. Col. G.C. Brant, at the time commandant of the Army Air Corps base at Crissy Field in San Francisco, would state, “The Guggenheim Experimental Airways Weather Service has done more to raise the morale of the Army Flying Corps than anything else that has happened since I became associated with it. Formerly a pilot did not know what was ahead, now he knows and is prepared.” [ 24 ]

A dazzling Lucille Ball is shown here after a flight on a Western Air Express Fokker F-10, a plane referred to as the “Queen of the Model Airline”.

Even though mail revenues still constituted the majority of income, and profitability solely from passenger service was still a few years away, the public relations impact, the technological advancements, and the lessons learned as a result of the model airline experiment would greatly facilitate eventual realization of profitability in the industry. Though there would be many ups and downs in the years to come, [ N 3 ] Western Air Express and the rest of the budding airline industry in America had positioned themselves on arguably the first path to sound economic success in the world of commercial aviation. Other carriers would soon follow Western Air Express’s lead in providing passenger service across the nation, with increasingly safe and cost effective passenger aircraft. America was officially on its way to emerging as a global leader. Western would even stake its claim not only as a domestic pioneer but as “ the world’s first economically successful venture in airplane transportation ” [ 27 ] . (See this referred to on Western’s First Anniversary Flight Postcard) . One of the reasons Western was able to make this claim is that although commercial aviation in Europe and other places around the globe got off to a quicker start in many areas including number of passengers carried, this didn’t translate to profits. As Tom D. Crouch, senior curator of aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum, writes in Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age , “The pioneering postwar airline ventures in England, France, and Germany enjoyed some early successes. British and French air services carried sixty-five hundred passengers between London and Paris in 1920, with the three British operations carrying perhaps three times as many passengers as their French counterparts. At the same time, actual revenues amounted to only 17 percent of total costs.” [ 28 ] Many of these European ventures would not be long lived as a result of the unsound economics. And even many of those that did survive like KLM (officially the world’s oldest airline) would do so not because of economically successful operations in those days but because they were largely supported by government subsidies, unlike Western Air Express. [ 29 ] [ 30 ] [ N 4 ] As Woolley writes again in Airplane Transportation , “To secure consideration of the airplane as a commercial vehicle required, in Europe, direct financial assistance from government; in the United States, only evidence of its economic worth.” [ 31 ] And in 1936, Col. E.S. Gorrell, then president of the Air Transport Association of America, said of a partnership between five of the major airlines to build a 40-passenger super-airliner, “This contract marks a significant step for advancement of commercial aviation. Unlike every other country, where heavy government subsidies are devoted to the development and advancement of air transport aircraft, private enterprise in the United States, the individual operator, must carry this entire burden.” [ 32 ] [ N 5 ]

EXPONENTIAL GROWTH

When C.G. Grey, the editor of the English aeronautical journal Flight , arrived in New York in January 1925 to gauge the state of aeronautics in the United States. he commented, “The general atmosphere of aviation in America impressed one as being in a state when something is about to happen. Not so much the calm before the storm, but rather the slump before the boom.” [ 33 ] These words would prove to be prophetic as the U.S. airline industry would grow exponentially after 1926. With less than 6,000 airline passengers in the United States recorded in 1926, this would grow to approximately 173,000 in 1929, and a decade later this number would be approximately one million passengers. [ 34 ] [ 35 ] [ N 6 ] Col. E.S. Gorrell again commented in 1936, “Air passenger traffic has increased at a more rapid rate in the United States than anywhere else in the world, largely due to superior aircraft and operations methods. In the past five years passengers carried on domestic and foreign airlines under the American flag have increased from 385,000 in 1930 to nearly 1,000,000 in 1935.” [ 36 ] Passenger airtravel had become a reality. The U.S. aviation industry would eventually go on to represent the largest single market in the world, accounting today for over one‐third of the world’s total air traffic [ 37 ] (in addition to claiming the world’s largest airline, American Airlines). It may also be said that an even brighter future yet awaits it. In fact, by the year following the upcoming centennial of that inaugural passenger flight of Western Air Express (2027), the FAA projects air travel demand in the U.S. to top 1 billion passengers per year. [ 38 ]

At the same time, the real birth of commercial aviation is not merely a story of a landmark flight or even that of a handful of pioneers and philanthropists. It is the story of a nation. In order to make possible the conditions for success, many pieces needed to come together. And this would involve one of the greatest collaborative efforts in all of human history

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR SUCCESS

During the first decade or so following the Wright Brother’s first flight, America lagged behind Europe with regard to aviation. As C.V. Glines writes in an article published in the the November 1996 edition of Aviation History magazine:

The United States clearly was in the doldrums so far as aviation was concerned. By contrast, a year after the armistice, Britain and France were operating scheduled flights between London and Paris. The Germans had an all-metal transport 10 years before William Stout designed one for Henry Ford. The French had an internal airmail system that far outdistanced the United States’ fledgling airmail service. Italy’s Gianni Caproni had built a 100-passenger, eight-engine flying boat. And even the Russians, as far back as 1913, had a four-engine airliner designed by Igor Sikorsky that boasted an enclosed cockpit and passenger cabin, electric lights and a washroom. [ 39 ]

But even as America itself was founded in a story of “beating the odds”, so too would this generation of Americans rise up to meet the challenge before it – heeding the wisdom of the words spoken by one of the nation’s brightest businessmen and entrepreneurs of the time, Henry Ford: “When everything seems to be going against you, remember that the airplane takes off against the wind, not with it.” A movement would soon take off in America that would change its fortunes – a movement that would find its impetus when the U.S. Government first began experimenting with the use of planes to transport mail.

In 1917 Congress, acting on a recommendation from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) which would later become NASA, appropriated $100,000 for the creation of an experimental airmail service. This would include involvement from both the Army and the Post Office. One of the contributions from the Army was providing pilots to fly the mail planes – a particularly dangerous job. In fact, during the period the Post Office operated the air mail, the life expectancy of a Mail Service pilot was only four years, and thirty one of the first forty pilots were killed in action. [ 40 ]

The Army also assisted with the initial deployment of rotating beacons that would make it possible to fly the routes at night. The Post Office would take over soon afterwards, expanding the guidance system the following year to make transcontinental air service possible. By 1923, mail could be delivered from one coast to the other in two days less time than by train.

Once the basic infrastructure was in place for airmail to work, the U.S. Government sought to transfer this service to private companies. As described in The Airline Handbook from Airlines for America (America’s oldest and largest airline trade association):

“Once the feasibility of airmail was firmly established and airline facilities were in place, the government moved to transfer airmail service to the private sector by way of competitive bids. The legislative authority for the move was granted by the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925, commonly referred to as the Kelly Act after its chief sponsor, Rep. Clyde Kelly of Pennsylvania. This was the first major step toward the creation of a private U.S. airline industry. [emphasis added]” [ 41 ]

Through a balance of government and private industry very much in harmony with the spirit of America, the stage was set for the dawning era in the history of aviation. The U.S. government through its numerous efforts to facilitate aviation nationwide would provide essentially a “hand up” to private enterprise, then largely get out of the way – even though it would step in once again though the Air Commerce Act of 1926 in order to provide needed coordination as well as a set of essential checks and balances. [ N 7 ] As described again in The Airline Handbook :

“The same year Congress passed the Contract Air Mail Act, President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board to recommend a national aviation policy (a much-sought-after goal of then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover). Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in J.P. Morgan’s bank, and later the father-in-law of Charles Lindbergh, was named chairman. The board, popularly known as the Morrow Board, heard testimony from 99 people and, on Nov. 30, 1925, submitted its report to President Coolidge. The report was wide-ranging, but its key recommendation was that the government should set standards for civil aviation and that the standards should be set outside of the military. “Congress adopted the recommendations of the Morrow Board almost to the letter in the Air Commerce Act of 1926. The legislation authorized the Secretary of Commerce to designate air routes, to develop air navigation systems, to license pilots and aircraft and to investigate accidents. The act brought the government into commercial aviation as regulator of the private airlines that the Kelly Act of the previous year had spawned.” [ 42 ]

Through these acts of Congress in 1925 and 1926, the essential framework had been established, and the ground was ripe for the birth of a new industry. In fact, the initial Contract Air Mail (CAM) service carriers selected through this process would in time and through mergers and acquisitions go on to become key players in the airline industry, including American Airlines, United Airlines, Western Airlines (which as mentioned would eventually be acquired by Delta Airlines, who was also a CAM carrier beginning in 1934), Boeing, Pan Am, Trans World Airlines (TWA), Northwest Airlines, Braniff, Continental, and Eastern Airlines. These would also greatly influence the advancement of technology and infrastructure that would allow passenger airtravel to survive and prosper in the decades to follow.

Initial Contract Air Mail (CAM) Routes

Starting with an initial group of five, a total of 34 Contract Air Mail routes would eventually be established in the U.S. between February 15, 1926, and October 25, 1930.

The “first five” CAM contractors would include:

1926 – A WATERSHED YEAR FOR COMMERCIAL AVIATION

The aforementioned book Airplane Transportation by James Woolley was used as a textbook at the University of Southern California and several other schools. With contributing works from famed meteorologist Carl-Gustav Rossby and William P. MacCracken, Jr., the first federal regulator of commercial aviation appointed in 1926, its emphasis was to teach the business elements of the arising “new industry” to all those eager to acquire “knowledge of the airplane and its potentialities as an agency of commerce”. [ 43 ] In the opening of the first chapter, Woolley describes the state of commercial aviation in the eyes of the nation at the time:

“Within the past two years America has awakened to the presence of a new and vital agency in transportation; a medium, which, although at present only slightly understood, holds promise of development beyond grasp of the most vivid imagination. True, the airplane as a vehicle has been known to us for more than one-quarter century but its adaptation to commerce dates only from the termination of the World War and its economic worth had not been definitely established previously to 1926.” [ 44 ]

1926 was a watershed year for commercial aviation. It would be one of many key milestones, and one that would see the first economic successes.

As mentioned, 1926 would be the year of what has been referred to as the first true commercial passenger flight in the United States. Additionally, the Federal Aviation Association’s most recently published chronology dates back to that year (FAA Historical Chronology, 1926-1996), beginning with the Air Commerce Act. And in 1976 – coinciding with the nation’s bicentennial – the U.S. Post Office would issue the Commercial Aviation Commemorative Stamp marking the “golden anniversary of commercial aviation in the United States” with the description “Commercial Aviation, 1926-1976″ ( See the first day of issue cover for this stamp ).

The Commercial Aviation Commemorative Stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1976

1926 being the year the “CAM” carriers would began carrying U.S. Air Mail under contract, the planes shown on the 1976 stamp were the first two to do so: the Ford-Stout AT-2 (upper) and Laird Swallow (lower).

Other groups, such as the Aviation Historical Society, would also honor 1926 as the true beginning of U.S. commercial aviation (as shown below).

An enveloper cover from the Aviation Historical Society Honoring the 50th Anniversary of U.S. Commercial Aviation

In addition to numerous legislative and general infrastructure advancements, there were other factors as well that led to the growth of passenger airtravel in the United States beginning in the mid-1920s. One of those can be attributed to the contributions of automobile pioneer Henry Ford. In 1925, Ford began a commercial cargo airlines called the Ford Air Transport Service and would be awarded the CAM6 and CAM7 airmail routes. Although not receiving one of the initial five routes, he would actually be the first of the carriers to begin operation in 1926, staking the company’s claim as “the world’s first regularly scheduled commercial cargo airline.” [ 45 ] He would soon abandon that venture however in favor of focusing on airplane manufacturing, selling its routes to Stout Air Services (which was eventually acquired by National Air Transport (NAT) who in turn became part of United Airlines).

It was in two primary areas that Ford would help shape the history of commercial aviation. The first of those was in airplane technology, through the introduction of the Ford Trimotor – the first all-metal, multi-engine transport in the United States and the first plane designed primarily to carry passengers rather than mail (having room for 12 passengers and cabins with high ceilings that didn’t require stooping).

The Trimotor’s three-engine design made for significant improvements in relation to speed and altitude – ultimately enabling it to become the first plane to be used for transcontinental passenger service, as well as the first plane to fly over the South Pole. Dubbed the “Tin Goose”, a total of 199 Ford Trimotors were built between 1926 and 1933. And its impact on commercial aviation was immediate, with the design helping to make passenger airtravel potentially profitable for the first time. It would be labeled as the “first successful American airliner” and said to represent a “quantum leap over other airliners.”

Ultimately, the Great Depression ended Henry Ford’s short career as a major figure in American aviation. He would pass the baton to companies like Boeing, who introduced the Boeing 247 in 1933, and the Douglas Aircraft Company whose DC-3 would revolutionize air transportation for the next decades (along with Wright Aeronautical and Pratt and Whitney who would dominate the engine market for years to come). In the meantime, however, United Aircraft and Transport Corporation took over the Ford airmail routes in 1929 and the Ford Airplane Manufacturing Division closed for good in 1933. Though similar to the way Ford’s durable Trimotor planes seemed to last forever (One Trimotor 5-AT, built in 1929, was still being used in Las Vegas for sightseeing in 1991), [ 46 ] so was Ford’s impact on commercial aviation long lasting. Not only did the advancements in plane construction help move the industry forward, but Ford was also instrumental in a second important breakthrough: gaining the American public’s trust when it came to flying.

When the public saw that Ford had its name on airplanes used for passenger service, it gave an entirely new level of legitimacy to the idea of safe and reliable passenger airtravel. As famous 1920s and 1930s actor Will Rodgers would comment, “Now you know that Ford wouldn’t leave the ground and take to the air unless things looked pretty good to him up there.” [ 47 ]

Ford’s involvement in airplane manufacturing, coupled with the government legislation of 1925-1926, provided a stamp of approval in the eyes of the public and for the first time ever passenger flight began to be seen not as merely a novel and risky venture, but as a new and trustworthy way of travel. In fact, just as Ford traveled around the country through his “Reliability tours” to promote the idea that the automobile had come of age in America, so did he do the same for the airplane – in part through the aerial version of his Reliability Tours, the Ford National Reliability Air Tour.

CHARLES LINDBERG

The Airline Handbook describes the bold and revolutionary accomplishment:

“In planning his transatlantic voyage, Lindbergh daringly decided to fly by himself, without a navigator, so he could carry more fuel. His plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, was slightly less than 28 feet in length, with a wingspan of 46 feet. It carried 450 gallons of gasoline, which constituted half its takeoff weight. There was too little room in the cramped cockpit for navigating by the stars, so Lindbergh flew by dead reckoning. He divided maps from his local library into thirty-three 100-mile segments, noting the heading he would follow as he flew each segment. When he first caught sight of the coast of Ireland, he was almost exactly on the route he had plotted, and he landed several hours later, with 80 gallons of fuel to spare. Lindbergh’s greatest enemy on his journey was fatigue. The trip took an exhausting 33 hours, 29 minutes and 30 seconds, but he managed to remain awake by sticking his head out of the window to inhale cold air, by holding his eyelids open, and by constantly reminding himself that if he fell asleep he would perish. In addition, he had a slight instability built into his airplane, which helped keep him focused and awake. Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget Field, outside of Paris, at 10:24 p.m. Paris time on May 21. Word of his flight preceded him and a large crowd of Parisians rushed out to the airfield to see him and his little plane. There was no question about the magnitude of what he had accomplished. The age of aviation had arrived.” [ 48 ]

As a young U.S. Air Mail pilot hired in 1925 by the Robertson Aircraft company (that would later become American Airlines) to fly the CAM-2 mail route between St. Louis and Chicago, Lindbergh was suddenly thrust into the spotlight as an American hero, as well as the first person to ever be in New York one day and Paris the next. It captured the imagination of the public in relation to the capabilities of modern airtravel, as well as the imagination of investors. Though many in years past had invested in aviation ventures that had failed, suddenly there was a rush to Wall Street to invest in aviation, with investments in aviation stocks tripling between 1927 and 1929.

After his legendary feat, Lindbergh was faced with enthusiastic crowds wherever he went. He gave numerous speeches, participated in parades, and received many awards, including the Distinguished Flying Cross medal from President Calvin Coolidge, using his status as an American icon and international celebrity to further aviation along with other noble causes.

THE GUGGENHEIMS

As mentioned, the Guggenheim family also served as an important catalyst in the rise of commercial aviation. And this involved far more than generous financial contributions. The philanthropic efforts of the Guggenheims were far reaching and brought together some of the brightest minds in the nation. Tom Crouch writes again in Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age :

“Daniel Guggenheim began to discuss the possibility of expanding his involvement, spending several million dollars on the creation of a fund that would support civil aviation. Father and son, the Guggenheims discussed the idea with everyone from Orville Wright to Secretary of Commerce Hoover and President Coolidge. The decision to forge ahead had been made by January 1926. The Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics would support aeronautical education; fund research in “aviation science”;promote the development of commercial aircraft and equipment; and “further the application of aircraft in business, industry and other economic and social activities of the nation.” Running it would be a blue-ribbon panel of leading figures from aviation, business, finance, and science, including the inventor of the airplane and a Nobel laureate in physics.” [ 49 ]

The fund would go on to create schools of aeronautics at major universities, including Stanford, MIT, and Harvard, among several others. The impact would be far reaching with respect to the research conducted, the technological discoveries made, and perhaps most importantly the development of the graduates – from pilots to engineers to meteorologists.

One of those graduates was Herbert Hoover, Jr., son of 31st President of the United States Herbert Hoover and eventual Secretary of State under President Eisenhower. Hoover won a fellowship from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund to study aviation economics at the Harvard Business School, and would focus on the economics of radio in the aviation sector. He would use that education to help Western Air Express, in cooperation with Thorpe Hiscock of Boeing, to develop the first ever air-to-ground radio while serving as Western’s communication chief.

Under his guidance, Western would also establish a system capable of guiding radio-equipped aircraft along 15,000 miles of airways across the Western U.S. And in 1930 he would be elected president of Aeronautical Radio Inc. – a non-profit alliance between Western Air Express, Boeing and American Airways that represented the airline industry’s single licensee and coordinator of radio communication outside of the government. This selection led to Time Magazine putting Hoover on the cover of its July 14, 1930 edition.

Herbert Hoover Jr (middle) with Western Air Express pilots Jimmie James (left) and Fred Kelly (right)

Even beyond education, the Guggenheim fund would make major contributions to the aviation industry. An example was its revolutionary breakthroughs in relation to “blind flight”, addressing the problems faced by pilots in three main areas: point-to-point navigation while in fog or above clouds, maintaining straight and level flight via instrument readings, the usage of ground facilities for take off or landing assistance in poor visibility conditions.

In September 1929, a young U.S. Army lieutenant named James Doolittle took off from Mitchell Field in New York on a 15-minute test flight. When his wheels touched down, he had reached a major milestone in aviation history, being the first plane in history to take off, fly a precise flight path, and land, with its pilot not using any visual cues outside of his cockpit instruments. The instruments that made this possible included a very accurate barometer, an artificial horizon and gyroscope, and a radio direction beacon – all developed through research at the Guggenheim Full Flight Laboratory. Within the next decade, instrument flying would become routine for all airlines. One of the congratulatory telegrams sent to Harry Guggenheim upon this achievement came from famed explorer Robert E. Byrd, who sent the message from his camp on the Antactic ice cap. At the end, he added “I know of nothing that has done as much for the progress of aviation as your organization.” [ 50 ] The Guggenheim Fund would end in 1930, concluding very much in the same spirit of the U.S. government’s previous involvement in helping aviation to forge ahead. Daniel Guggenheim would state, “With commercial aircraft companies assured of public support and aeronautical science equally assured of continual research, the further development of aviation in this country can best be fulfilled in the typically American manner of private business enterprise.” [ 51 ]

Though the fund would cease, however, its impact would live on – as would the Guggenheim’s work through other avenues. The Guggenheim foundation for example established such entities as the Cornell-Guggenheim Aviation Safety Center at Cornell University where important research took place in relation to collision avoidance, crash fire protection, and other aspects of safety improvement. The Guggenheim Medal fund would be awarded annually to individuals making exceptional contributions to aviation, with the first going to Orville Wright. And the Guggenheims sponsored much of the research of Dr. Robert J. Goddard, upon which all modern developments of rockets and jet propulsion was based.

Arguably though, the greatest impact of the Guggenheim legacy remains that of the decision to provide funding to a courageous group of aviation trailblazers and the establishment of the world’s first “model airline”. Together, the Guggenheims and Western Air Express would pioneer the first semblences of airtravel as we know it today – year round, regularly scheduled, overland service using landplanes – and pave the way for the first truly self sustaining and economically successful model in commercial aviation.

The legacy and impact of the Guggenheim Fund would live on many years past the end of the model airline experiment, as would that of Western which would go on to establish many industry firsts [ N 8 ] . In fact, Western would eventually take on the label of “America’s senior air carrier” as well as the “oldest continuously operating airline in the US” [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ N 9 ] at the time of its acquisition by Delta in 1986. Even as it became part of the Delta family, the innovations and progress of Western, much of which was derived from its earliest years, [ N 10 ] would carry on not only in spirit but in everyday business operations. To this day, for instance, Delta continues Western’s Salt Lake City hub operations, which is the same location from where that first passenger flight of Western Air Express took place in 1926 – an event that would set in motion the first true success story in commercial aviation.

When history is remembered, what generally emerges to the forefront are not necessarily the “firsts”, but the events, discoveries. and individuals that had the most powerful influence in shaping the future.

Christopher Columbus was not the first to discover America. Yet the fact that his name looms larger in history than many of those who proceeded him – including the Vikings led by Leif Erickson, the waves of Carribean explorers like the Taino tribe, and potentially even Monks like St. Brendan who it is believed made the journey in the sixth century – is because of the unparalleled impact of his explorations. Christopher Columbus opened up a new continent to Spain and, ultimately, all of Europe. His discovery had a profound and lasting impact on the trade routes of the day. And his voyages would ultimately reshape the known world.

Similarly, Henry Ford did not invent the automobile and yet his name is synonymous with it. For it is he who changed the landscape of a nation, and world, by making the automobile an affordable reality to the average person. Through use of the assembly line technique of mass production, and by lowering costs as opposed to pocketing profits from the resulting cost savings, Ford’s company would go on to lead the American industry to produce three quarters of all automobiles in the world by 1950.

Taking transportation to the next level would be the Wright Brothers, even though technically they were not the first to fly manned aircraft. In addition to those lifted by hot air balloon and airships such as Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier who flew the first manned free balloon flight on November 21, 1783, there are others who flew heavier-than-air crafts in the rough form of the modern day airplane beginning in the early 1800s. And while many of the pioneers who did so would make significant contributions to the science and eventual realization of powered flight (which the Wright Brothers themselves would even rely upon), the Wright Brothers hold a special place in history because of the unique impact they had on airplane design. While other early inventors experimented with the shifting of a persons weight to control or steer the plane, for instance, the Wright Brother’s revolutionary invention of “three-axis control” would make fixed-wing powered flight truly possible for the first time ever and would be adopted universally in aircraft design moving forward. Tom D. Crouch, who as mentioned holds the position of senior curator of aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum, described why the invention of the Wright Brothers is given precedence as first to achieve “powered, heavier-that-air flight” over the work of competing inventor Augustus Moore Herring, saying “Herring’s 1898 motorized machine represented nothing more than the culmination of the hang-gliding tradition. Having made his brief powered hops, he found himself at a technological dead end.” [ 54 ]

In a similar way, there were various early attempts to launch the world of commercial aviation, ranging from paid sightseeing flights on crop dusters to a handful of failed airboat ventures. But perhaps the most significant breakthrough came via a great American success story – that of the Guggenheims and Western Air Express, and of the movement of the mid-1920s that involved one of the greatest collaborations in human history. From the legislation that laid the early groundwork to the humble beginnings of a two-passenger inaugural flight in an open cockpit atop mail sacks to the investments made by many, this is a story of American ingenuity, of the unique American balance between government and private enterprise, and of the spirit of the American West.

These truths are emphasized not merely in the spirit of American patriotism, but more so in the spirit of the model airline experiment – that the success of one might benefit many (also an American principle). For the hope is that the blueprint discovered here might lead others to greater successes, whether nations or groups of individuals or other generations of Americans. After all, it is poetic that the movement which brought forth the kind of advancements that would connect the world as never before, was done through such a great collaboration of people. The profound words found on the website for the Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company seem most fitting in this regard, describing one of the true motivations that drove the two brothers to pursue their dream of building their flying machine: “Seen from above, the artificial boundaries that divide us disappear. Distances shrink, the horizon stretches. The world seems grander and more interconnected.” [ 55 ] And Western Air Express pilot Al DeGarmo said of his friend and famed Hollywood actor Will Rogers, “He believed air travel was key to this country’s growth. Air travel was something everyone would be doing one day, he said, and it would help break down differences that divided nations.” [ 56 ]

Today the Wright Brothers are recognized as among the greatest of the pioneers of flight – though it wasn’t until after they died that they were finally credited over such men as Samuel Pierpont Langley as being the first to build a heavier-than-air craft capable of manned powered flight. It sometimes takes time for the truest heroes of history to be appropriately honored. Hopefully this story of the beginning of commercial aviation will be told with greater attention paid to these great men and women who took the baton from the Wright Brothers and brought aviation to the next stage of development. For while the Wright Brother’s sought and achieved sustainable (and controlled) flight, these pioneers of the mid-1920s sought and achieved sustainable economic growth that would make it possible to take the innovations of the Wright Brothers and turn them into the means of forever changing the world of global transportation.

- ^ It is worth noting that the Guggenheims didn’t expect to be paid back for this loan and in fact told Western Air Express founder Harris Hanshue this was more in the nature of a grant. However, Hanshue refused to accept the money as a gift and insisted on inserting a clause into their agreement that stipulated Western was to repay the loan within eighteen months at 5% interest. Hanshue also put up some $100,000 in public-utilities securities to guarantee the loan.

- ^ Robert Serling writes on pages 6-7 of The Only Way to Fly: The Story of Western Airlines America’s Senior Air Carrier , “…there is one thing to be noted about all these early airline efforts [prior to 1926] – every one involved the use of flying boats, not landplanes. Airfields throughout the United States, with few exceptions, were too primitive, inadequate, and actually dangerous to warrant confidence on the part of the public or airmen themselves. Not until the government – prodded by the growing demand for regular air mail service-established lighted airways and modest airport improvements did scheduled air transportation become feasible between inland cities.”