HMS Beagle: Darwin’s Trip around the World

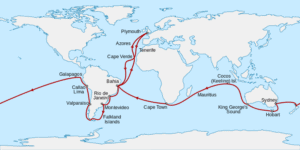

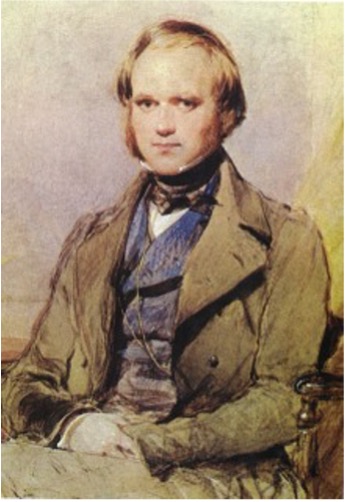

Charles Darwin sailed around the world from 1831–1836 as a naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle . His experiences and observations helped him develop the theory of evolution through natural selection.

Biology, Geography, Earth Science, Geology, Ecology

Loading ...

Idea for Use in the Classroom

Charles Darwin set sail on the ship HMS Beagle on December 27, 1831, from Plymouth, England. Darwin was 22 years old when he was hired to be the ship’s naturalist . Most of the trip was spent sailing around South America. There Darwin spent considerable time ashore collecting plants and animals. Darwin filled notebooks with his observations of plants, animals, and geology . The trip was an almost five-year adventure and the ship returned to Falmouth, England, on October 2, 1836.

Throughout South America, Darwin collected a variety of bird specimens . One key observation Darwin made occurred while he was studying the specimens from the Galapagos Islands. He noticed the finches on the island were similar to the finches from the mainland, but each showed certain characteristics that helped them to gather food more easily in their specific habitat. He collected many specimens of the finches on the Galapagos Islands. These specimens and his notebooks provided Darwin with a record of his observations as he developed the theory of evolution through natural selection .

Have students work in pairs to use the map and the resources in the explore more tab to create a social media feed that includes five dates and posts from the expedition. Students may need to conduct additional research to ensure their proposed posts are factual and something Darwin would have seen on the trip. Help students brainstorm ideas for their posts by asking: What types of animals would Darwin have seen? Are any of them extinct today? What types of plants did he note? What types of geology did he see? What would you imagine some of the hardships the explorers would have encountered on this voyage?

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- International

- Education Jobs

- Schools directory

- Resources Education Jobs Schools directory News Search

Beagle Voyage of Charles Darwin Complete lesson KS2

Subject: Primary science

Age range: 7-11

Resource type: Lesson (complete)

Last updated

3 November 2022

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

A complete lesson with the LO: to understand Darwin’s voyage on HMS Beagle.

During the lesson, students will map the voyage and key events on each stop of the journey.

All resources are included, although internet access may be required for the higher attainers to research additional information, using the Beagle diaries (Link included in the resources)

All other images from Pixabay or authors own.

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

- Project Gutenberg

- 74,457 free eBooks

- 54 by Charles Darwin

The Voyage of the Beagle by Charles Darwin

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

Charles Darwin Facts & Worksheets

Charles darwin facts and information plus worksheet packs and fact file. includes 5 activities aimed at students 11-14 years old (ks3) & 5 activities aimed at students 14-16 years old (gcse). great for home study or to use within the classroom environment., download charles darwin worksheets.

Do you want to save dozens of hours in time ? Get your evenings and weekends back? Be able to teach about Charles Darwin to your students?

Our worksheet bundle includes a fact file and printable worksheets and student activities. Perfect for both the classroom and homeschooling!

Download free samples

Resource Examples

Click any of the example images below to view a larger version.

Student Activities

Early Life and Education

Voyage of the beagle, evolution by natural selection, personal life, key facts and information, let’s know more about charles darwin.

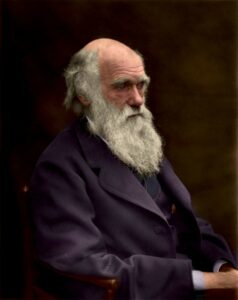

Charles Robert Darwin was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist who developed the theory of evolution through the process of natural selection. His theory that all living things originated from common ancestors is now generally recognised and regarded as a fundamental scientific concept. As the most prominent proponent of this idea, Darwin holds a unique place in history. While he lived a fairly quiet and studious life, his works were controversial in their day and still routinely spark controversy.

- Charles Robert Darwin was born on 12 February 1809 in Shrewsbury, England, to a wealthy family. He was the fifth of six children. His grandfather was Erasmus Darwin, a successful doctor, and scientist who had previously made substantial contributions to evolutionary science. Robert Darwin, his father, was also a doctor and had amassed a fortune by wisely investing the proceeds from his medical practice. Susannah Wedgwood, a member of the famous pottery family, was Charles’ mother. She died when Charles was eight years old. He then enrolled in a primary school.

- Charles was sent to Shrewsbury School, approximately a mile from his family’s house, when he was nine years old. He boarded there and returned home frequently to keep up with his family’s activities. Charles despised the typical classical curriculum of his boarding school, which focused on Ancient Greek and Latin. He wasn’t thought to be particularly intelligent. His ability to communicate in a foreign language was limited. His education mainly consisted of memorising lines from Roman or Greek literature for the next day.

- Even though he despised it, he was content to put in long hours. He memorised his lines in detail, only to forget them all as soon as class was done. He liked hunting and lengthy hikes in the woods, studying and collecting natural objects.

- His brother set up a chemical lab in the garden tool shed, and Charles volunteered to help with experiments, often late at night. His favourite subject was chemistry. Regrettably, it was not included in his school’s curriculum. In fact, his headmaster scolded him for ‘wasting his time’ on chemistry.

- Charles enrolled at the University of Edinburgh as a medical student in 1825, at the age of 16. Charles, unlike his father, did not like medical school. He chose not to worry about completing his exams since he was confident that his father would provide him with enough money to live comfortably.

- Charles got interested in zoology in his second year at Edinburgh, and he began collecting and dissecting marine species. He also went to geology courses, although he considered them to be quite dull. Charles’ medical studies were put on hold by his irritated father. He withdrew his son from Edinburgh and sent him to Cambridge University, hoping that his lazy son would become a Church of England clergyman.

- Charles Darwin started at the University of Cambridge to study for a Bachelor of Arts degree in early 1828, just before his 20th birthday. After three easy years, he obtained his BA with grades that put him towards the top of the class. He’d spent a lot of time hunting, eating, drinking and playing cards, which he genuinely liked.

- Darwin was offered a position as a naturalist on HMS Beagle , one of the British Royal Navy survey ships, at the end of summer 1831, after completing his degree. The job had been offered to John Henslow, a Cambridge geologist and naturalist, but he had declined and suggested Darwin instead.

- While sailing south from the British Isles, the Beagle’s first stop was at the volcanic Cape Verde Islands, west of Africa. Darwin discovered seashells on the cliffs nearby. The captain of the Beagle , a naturalist, assisted Darwin in explaining the finding by providing him with a copy of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology .

- Principles of Geology described uniformitarian notions in geology, such as James Hutton’s gradualism hypothesis, which was initially suggested late in the previous century. Charles Lyell, the book’s author, would become one of Darwin’s closest friends and supporters a few years later.

- Darwin kept writing about his adventures in each new location he visited, collecting samples of flora, animals and fossils, and analysing geological formations. On the Galapagos Islands, he witnessed a wide range of strange and unique creatures. Each island seems to have its own unique species of wildlife.

- In October 1836, Darwin returned to England. He had maintained contact with John Henslow, giving him notes on his geological work on the trip on a regular basis.

- He compiled his observations into a 31-page pamphlet, which he disseminated widely across Cambridge’s scientific community. Henslow also exhibited Darwin’s fossils, which sparked even more interest.

- His father was relieved that his prediction that Charles would bring the family into disgrace had proven to be wrong. In the field of natural science, Charles Darwin was now admired, and his father consented to continue sponsoring his research. In reality, other people saw the worth in Darwin’s work, and the British government gave him a large grant to write up his observations from the Beagle’s expedition.

- Despite the fact that Darwin set sail as an unknown graduate, he returned as a renowned and well-known scientist. He also amassed a big and intriguing collection of specimens, which naturalists were eager to study and classify.

- Darwin discovered that the continent of South America is gradually rising from the sea. Darwin presented this paper to the Geological Society of London at the beginning of 1837, thanks to Charles Lyell, whose geology book influenced Darwin on the voyage.

- Darwin also exhibited specimens of birds he had gathered from the Galapagos Islands at the same meeting. Within a week, naturalist John Gould had inspected the specimens and determined that the birds belonged to a whole new species of finch. Twelve new bird species and a new finch group were discovered by Darwin.

- On his long voyage, at times fascinated by nature’s abundance, Darwin’s thoughts had increasingly turned to the question of how different species had formed. Thousands of years before Darwin’s time, the notion of evolution had been developed. Erasmus Darwin, his grandfather, had made several significant contributions to evolutionary theory, including the concept of a common origin for all life.

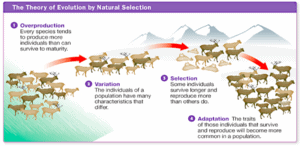

- By December 1838, Darwin had pondered how breeders could enhance domestic animals by choosing the best individuals. In the natural world, the environment does the selection. Natural selection ensures that the lifeforms that are most adapted to their surroundings survive and reproduce.

- He presented his opinions on the new species of finches he discovered in the Galapagos Islands in 1845, claiming he could imagine that one original species had been modified into all the numerous species that he had developed much earlier.

- gathering and weighing evidence from his journey, as well as evaluating specimens;

- breeding animals and plants to see how artificial selection may change species; and

- writing books and papers about a variety of topics including geology.

- On 24 November 1859, Charles Darwin’s game-changing book On the Origin of Species – generally referred to as the most important book in the history of biology – was released to the public, and all 1250 copies were quickly sold.

- Darwin avoided making any claims for the origin of a specific species, such as Homo sapiens, in order to avoid dispute. He did however, in agreement with his grandfather’s much earlier theory, write: “...probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed”.

Darwin continued to update the book throughout the years. He went on to write six distinct editions of the book. Some of Darwin’s most well-known concepts did not emerge until subsequent editions: the famous term ‘survival of the fittest’ only appeared in the 1869 fifth edition. Remarkably, the term ‘evolution’ first appeared in the sixth edition of the book in 1872.

- On 29 January 1839, Darwin married Emma Wedgwood. He was 29 years old, and she was 30. They were first cousins. The couple had ten children, three of which died in childhood. George, Francis and Horace, three of their sons, were prominent scientists and were elected fellows of the Royal Society. George went on to study astronomy, Francis botany, and Horace engineering. Leonard, another son, helped to fund the publishing of Ronald Fisher’s first book.

- Darwin became unwell in 1837, just as he began working on a multi-volume collection of findings from the Beagle trip and began actively exploring species transmutation. He would be plagued by ill health for the rest of his life.

- In 1842, he and his family relocated to a country residence outside of London, away from the pollution and smog. He led a solitary existence, rarely mingling and instead focusing on his family and publishing books and scholarly articles. Darwin received the Copley Medal, the highest award in science at the time, in 1864.

- Charles Darwin died of heart failure at his country house on 19 April 1882, at the age of 73. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, London, alongside his best friend Charles Lyell, whose work had impacted him considerably, and next to John Herschel, whose work had inspired him at university. Isaac Newton, Ernest Rutherford, JJ Thomson and Lord Kelvin are among the scientists buried near Darwin in Westminster Abbey.

Image Sources

- charles-darwin-800x1008.jpg

- 800px-Voyage_of_the_Beagle-en.svg.png

- Screen-Shot-2019-10-18-at-7.00.53-PM.png

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- American History ›

Charles Darwin and His Voyage Aboard H.M.S. Beagle

The Young Naturalist Spent Five Years on a Royal Navy Research Ship

Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

The History of H.M.S. Beagle

Gentleman passenger, darwin invited to join the voyage in 1831, departs england on december 27, 1831, south america from february 1832, the galapagos islands, september 1835, circumnavigating the globe, back home october 2, 1836, organizing specimens and writing, the theory of evolution.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Charles Darwin’s five-year voyage in the early 1830s on H.M.S. Beagle has become legendary, as insights gained by the bright young scientist on his trip to exotic places greatly influenced his masterwork, the book " On the Origin of Species ."

Darwin didn’t actually formulate his theory of evolution while sailing around the world aboard the Royal Navy ship. But the exotic plants and animals he encountered challenged his thinking and led him to consider scientific evidence in new ways.

After returning to England from his five years at sea, Darwin began writing a multi-volume book on what he had seen. His writings on the Beagle voyage concluded in 1843, a full decade and a half before the publication of "On the Origin of Species."

H.M.S. Beagle is remembered today because of its association with Charles Darwin , but it had sailed on a lengthy scientific mission several years before Darwin came into the picture. The Beagle, a warship carrying ten cannons, sailed in 1826 to explore the coastline of South America. The ship had an unfortunate episode when its captain sank into a depression, perhaps caused by the isolation of the voyage, and committed suicide.

Lieutenant Robert FitzRoy assumed command of the Beagle, continued the voyage and returned the ship safely to England in 1830. FitzRoy was promoted to Captain and named to command the ship on a second voyage, which was to circumnavigate the globe while conducting explorations along the South American coastline and across the South Pacific.

FitzRoy came up with the idea of bringing along someone with a scientific background who could explore and record observations. Part of FitzRoy’s plan was that an educated civilian, referred to as a “gentleman passenger,” would be good company aboard ship and would help him avoid the loneliness that seemed to have doomed his predecessor.

Inquiries were made among professors at British universities, and a former professor of Darwin’s proposed him for the position aboard the Beagle.

After taking his final exams at Cambridge in 1831, Darwin spent a few weeks on a geological expedition to Wales. He had intended to return to Cambridge that fall for theological training, but a letter from a professor, John Steven Henslow, inviting him to join the Beagle, changed everything.

Darwin was excited to join the ship, but his father was against the idea, thinking it foolhardy. Other relatives convinced Darwin’s father otherwise, and during the fall of 1831, the 22-year-old Darwin made preparations to depart England for five years.

With its eager passenger aboard, the Beagle left England on December 27, 1831. The ship reached the Canary Islands in early January and continued onward to South America, which was reached by the end of February 1832.

During the explorations of South America, Darwin was able to spend considerable time on land, sometimes arranging for the ship to drop him off and pick him up at the end of an overland trip. He kept notebooks to record his observations, and during quiet times on board the Beagle, he would transcribe his notes into a journal.

In the summer of 1833, Darwin went inland with gauchos in Argentina. During his treks in South America, Darwin dug for bones and fossils and was also exposed to the horrors of enslavement and other human rights abuses.

After considerable explorations in South America, the Beagle reached the Galapagos Islands in September 1835. Darwin was fascinated by such oddities as volcanic rocks and giant tortoises. He later wrote about approaching tortoises, which would retreat into their shells. The young scientist would then climb on top, and attempt to ride the large reptile when it began moving again. He recalled that it was difficult to keep his balance.

While in the Galapagos Darwin collected samples of mockingbirds, and later observed that the birds were somewhat different on each island. This made him think that the birds had a common ancestor, but had followed varying evolutionary paths once they had become separated.

The Beagle left the Galapagos and arrived at Tahiti in November 1835, and then sailed onward to reach New Zealand in late December. In January 1836 the Beagle arrived in Australia, where Darwin was favorably impressed by the young city of Sydney.

After exploring coral reefs, the Beagle continued on its way, reaching the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa at the end of May 1836. Sailing back into the Atlantic Ocean, the Beagle, in July, reached St. Helena, the remote island where Napoleon Bonaparte had died in exile following his defeat at Waterloo. The Beagle also reached a British outpost on Ascension Island in the South Atlantic, where Darwin received some very welcome letters from his sister in England.

The Beagle then sailed back to the coast of South America before returning to England, arriving at Falmouth on October 2, 1836. The entire voyage had taken nearly five years.

After landing in England, Darwin took a coach to meet his family, staying at his father’s house for a few weeks. But he was soon active, seeking advice from scientists on how to organize specimens, which included fossils and stuffed birds, he had brought home with him.

In the following few years, he wrote extensively about his experiences. A lavish five-volume set, "The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle," was published from 1839 to 1843.

And in 1839 Darwin published a classic book under its original title, "Journal of Researches." The book was later republished as " The Voyage of the Beagle ," and remains in print to this day. The book is a lively and charming account of Darwin’s travels, written with intelligence and occasional flashes of humor.

Darwin had been exposed to some thinking about evolution before embarking aboard H.M.S. Beagle. So a popular conception that Darwin’s voyage gave him the idea of evolution is not accurate.

Yet is it true that the years of travel and research focused Darwin's mind and sharpened his powers of observation. It can be argued that his trip on the Beagle gave him invaluable training, and the experience prepared him for the scientific inquiry that led to the publication of "On the Origin of Species" in 1859.

- Biography of Charles Darwin, Originator of the Theory of Evolution

- World History Timeline From 1830 to 1840

- The Legacy of Darwin's "On the Origin of Species"

- Timeline from 1800 to 1810

- The First New World Voyage of Christopher Columbus (1492)

- History of the Plymouth Colony

- Timeline from 1880 to 1890

- The Mayflower Compact of 1620

- The Sinking of the Steamship Arctic

- A History of Camels In the US Army

- Atlantic Telegraph Cable Timeline

- The Resolute Desk

- American History Timeline 1601 - 1625

- Biography of John Rolfe, British Colonist Who Married Pocahontas

- The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- American Revolution: Battle of Nassau

Darwin's Beagle field notebooks (1831-1836)

The notebooks are arranged in the chronological order of their first entries. This is approximately the order in which they were originally presented by Barlow and corresponds to the small circled numbers written on some of the inside covers, we believe by Barlow (Chancellor 1990, p. 206 ).

Our order differs slightly from that adopted by Barlow in the position of the Galapagos notebook which she placed between the Despoblado and Sydney notebooks . Our order agrees with the list adopted by the editors of the Correspondence vol. 1, who consulted Chancellor when preparing their list. The list of notebook names given in the Correspondence is not always verbatim (e.g. there is no 'Santiago' on the cover of the Galapagos notebook and no 'Bathurst' on the cover of the Sydney notebook ).

Kees Rookmaaker, John van Wyhe and Gordon Chancellor.

This is a team edition; the initial transcription was prepared by Chancellor from microfilm in the 1980s, then checked, corrected against the microfilm and typed by Rookmaaker in 2006, re-checked by Chancellor then re-checked jointly by Chancellor, Rookmaaker and van Wyhe; then the three of us checked and corrected each notebook against the original manuscript or colour photographs. Finally van Wyhe re-checked the transcriptions of each notebook to ensure consistency. Van Wyhe annotated the notebooks, identifying persons and publications and so forth and added textual notes.

The role played by the field notebooks in the recording of Darwin's experiences during the voyage has been described by a number of authors from Barlow onwards (e.g. Armstrong 1985 ). Darwin used them to record in pencil his 'on the spot' observations, often while he was on long inland expeditions hundreds of kilometres from the Beagle , perhaps with no other paper to hand. A notable exception to this generalisation is the latter part of the Santiago notebook , which is effectively the first of Darwin's theoretical notebooks. In a letter to Henslow Darwin remarked that he was keeping his diary and scientific notes separate. But the field notebooks are documents prior to this distinction because they feed into both types of later manuscripts.

[A naturalist] ought to acquire the habit of writing very copious notes, not all for publication, but as a guide for himself. He ought to remember Bacon's aphorism, that Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man; and no follower of science has greater need of taking precautions to attain accuracy; for the imagination is apt to run riot when dealing with masses of vast dimensions and with time during almost infinity. ( p.163 )

Back on board ship, or in port, he used the notebooks while writing up in ink his geological, zoological and personal diaries. He refers to them in his Journal of researches , p. 24 'I see by my note-book, "wonderful and beautiful, flowering parasites," invariably struck me as the most novel object in these grand scenes.' (This from Rio notebook , 9 April 1832, p. 9b).

It may be wondered why Darwin did not use one notebook until it was full, rather than keep switching between notebooks. We believe that the main reason he kept switching was that for document security he would only take one notebook onshore, so once he was back on board after an excursion he would start to use the notebook just used as the basis for his various diaries and specimen lists, as explained by Armstrong 1985 . Since this process might take weeks, and therefore was often not completed before his next excursion, he preferred to take a notebook with him ashore which had already finished with, rather than risk losing field notes which had not yet been copied out. In this way he had a 'conveyor belt' of field notebooks in various states of use. We can only guess why he sometimes ended up with very incompletely used notebooks (e.g. the Banda Oriental notebook ) but perhaps this was because he preferred using some notebook types rather than others.

When first visiting Down House together to begin checking our transcriptions against the manuscripts, the curator, Tori Reeve, kindly brought out all of the notebooks together. However only three notebooks at a time were used on the work table. Van Wyhe was given permission to photograph the covers of the notebooks for private research. When these photographs were later arranged according to their first entry order of the notebooks it became apparent that there are six notebook types which were used almost chronologically, perhaps reflecting successive purchases by Darwin.

Cape de Verds , Rio , Buenos Ayres and B. Blanca

All four notebooks have red leather covers with blind embossed edges and are of a long rectangular shape (c. 130 x 80 mm) with integral pencil holders and brass clasps. The notebooks originally contained 112 pages. The paper bears the watermark 'J. Whatman 1830'. All of the original pencils, if they were included with the notebooks when purchased, are missing.

Falkland and R. N. (the well-known Red notebook published by Sandra Herbert in 1980 and 1987)

These two notebooks are long and rectangular (164 x 100 mm) and have brown leather covers with embossed floral borders and brass clasps. Herbert 1980 , p. 5 referred to the R. N. notebook 'as the name suggests, red in colour, although the original brilliance has faded'. Both notebooks are now brown though there are slight traces of red on Falkland which could be part of now lost colouring. The notebooks contained 184 pages, some bearing the watermark 'T. Warren 1830'. Darwin created a pencil holder inside the front cover of Falkland by pasting in a leather sleeve. Presumably this allowed him to carry one of the pencils that fit in the similar holders in the Type1 notebooks. The Red notebook has no added pencil sleeve, because it was not used in the field.

St. Fe and Banda Oriental

These two notebooks (155 x 100 mm) are bound in brown leather with brass clasps. Unlike preceding types they open like a book to the side rather than lengthwise like a pocket book. Only Santiago opens in the same manner. The notebooks were 244 pages long. The end pages and paper edges are marbled. Some pages have a watermark 'W. Brookman 1828'. A piece of cream-coloured paper pasted on the inside back cover of Banda Oriental secures a brown leather pencil holder added by Darwin.

Pages 4a-5a of the St. Fe notebook .

Port Desire

This This long and regtangular (170 x 130 mm) notebook is bound in brown leather with floral embossed borders and brass clasp. Its original back cover was missing (probably the one referred to by Barlow 1945, p. 154 ) but has since been restored. The fact that p. 137 right at the back of the notebook is very dirty seems to suggest that it was exposed. There were originally 146 pages, some of which bear incomplete watermarks which seem to read John Morbey 1830.

Valparaiso , Galapagos , Coquimbo , Copiapò , Despoblado and Sydney

These six notebooks are bound in red or black leather (the first and last are black) with the borders blind embossed and with brass clasps. Integral pencil holders, extensions of the cover leather as in Type 1, are placed on the left side of the front cover. The paper is yellow edged except for Sydney ( Galapagos is unknown). The notebooks are of an almost square shape varying from 90 x 75 to 120 x 100 mm and were between 100 and 140 pages long. This makes Type 5 the most variable of the notebooks and their spines have an undulating, almost lumpy appearance. The inside front covers bear printed labels surmounted by an engraved lion and unicorn:

VELVET PAPER MEMORANDUM BOOK.

So prepared as effectually to secure the writing from erasure; — with a METALLIC PENCIL, the point of which is not liable to break. The point of the pencil should be kept smoothly scraped flat & in writing it should be held in the manner of a common Pen.

The pages of the notebook were treated or coated to react with the metallic pencils, now lost. The paper remains bright white and has a silky or velvety feel. We are grateful to Louise Foster (personal communication) for very useful insights into the way the metallic pencils worked and for supplying us with various types of paper and metallic pencils to see how these influenced the effectiveness of the pencil. Although the writing in these books looks at first like graphite pencil it is in fact a reaction between the metal of the pencil point and the chemicals with which the paper was treated. This was meant to render the writing indelible.

Pages 36-37 of the Copiapò notebook .

This 100 X 165 mm notebook is bound in black paper with black leather spine and was originally 138 pages long. Four pencil holder loops, dovetailed along the opposite cover edges held the notebook closed when a pencil was inserted. This is not seen on any other Beagle notebook. The inside covers are green paper. Inside the front cover there is a collapsing pocket. The manufacturer's label shows that the notebook was made in France, unlike all of the other Beagle field notebooks. Santiago was probably used after the voyage and is labelled identically on both sides as is the Red notebook and the transmutation and expression notebooks, a post-voyage notebook labelling practice.

We are not aware of any other Darwin notebooks which match any of these field notebook types. Notebooks 1.1 , St. Helena Model , the specimen notebooks and all other post voyage notebooks are different types. Some of the Beagle notebooks, such as St. Fe and Valparaiso, have long fine, almost parallel, knife cuts on their covers. These may be where Darwin sharpened his pen or otherwise cut something on the notebooks. Possibly he used them in excising pages from other notebooks. The cuts were made before the notebooks were labelled. It is unknown when Darwin labelled the Beagle notebooks, but it was clearly after they were completed, and not all at once as he used different versions of place names, such as 'Isle of France' on the label of the Despoblado notebook but 'Mauritius' on the label of the Sydney notebook .

The appearance of the notebooks today is less battered and frayed than they were when Nora Barlow first described them in 1933. The 1969 microfilm images reveal flaps of torn leather on their covers and in one case ( Port Desire ) a back cover torn off. The edges of some of the leather covers were worn away. The notebooks have since been carefully conserved so that they appear in rather better condition then when they returned form the Beagle voyage. The Falkland , St. Fe , Banda Oriental and Port Desire notebooks , for example, have had missing pieces of their leather bindings restored.

The manufacturer's label shows that the notebook was made in France, but we suspect that Darwin purchased the notebook in St Jago. Unlike all of the other Beagle field notebooks, Santiago has a label pasted on both covers. This seems to be a practice Darwin adopted with his post-voyage notebooks (viz. the notebooks and ).

Editorial policy

The Beagle field notebooks are arguably the most complex and difficult of all of Darwin's manuscripts. They are for the most part written in pencil which is often faint or smeared. They were generally not written while sitting at a desk but held in one hand, on mule or horseback or on the deck of the Beagle . Furthermore the lines are very short and much is not written in complete sentences. Added to this they are full of Darwin's chaotic spelling of foreign names and cover an enormous range of subjects. Therefore the handwriting is sometimes particularly difficult to decipher. Alternative readings are often possible. Some illegible words are transcribed as well as possible, even when they are obviously not the correct word, when this seems more informative than just listing the word as illegible.

In the transcriptions we have strictly followed Darwin's spelling and punctuation in so far as these could be determined. The transcribed text follows as closely as possible the layout of the notebooks, although no attempt is made to produce a type-facsimile of the manuscript; word-spacing and line-division in the running text are not reproduced. Editorial interpolations in the text are enclosed in square brackets. The page numbers assigned to the notebooks are in square brackets in the margin at the start of the page to which they refer. Italic square brackets enclose conjectured readings and descriptions of illegible passages. Darwin's use of the ſ or long s (appearing as the first 's' of a double 's'), has been silently modernized. Darwin used an unusual backwards question mark (؟) which might be based on the Spanish convention of preceding a question with an inverted question mark (¿). Textual notes are given below each notebook. The notebooks are almost entirely written in pencil. Where ink was used instead this is indicated in the textual notes. Brown ink was used except where otherwise indicated. Pencil text that was later overwritten with ink is represented in bold font.

The length, complexity and need to refer to the textual notes has been minimized by representing some of the features of the original manuscripts typographically. Words underlined by Darwin are printed underlined rather than given in italics. Text that is underlined more than three times is double underlined and bold. (There are no instances of such entries also overwritten in ink.) Text that was circled or boxed by Darwin is printed as boxed (in the print volume by CUP only). Also text that appears to have been struck through at the time of writing is printed as struck through text. Darwin's insertions and interlineations have been silently inserted where he indicated or where we have judged appropriate.

Paragraphs are problematic; often Darwin ran all of his entries together across the page to save space. We have made a new paragraph when there was sufficient space at the end of the preceding line to have continued there. We have silently added a paragraph break wherever Darwin made a line across the page, apparently at the time of writing, or short double scores between lines separating blocks of text. When long strings of notes are separated with stops or colons and dashes we have left these as written by Darwin. We have ignored all later scoring through of lines, paragraphs and pages in the interest of readability. Virtually every page and paragraph is scored through, often several times, indicating that Darwin had made use of the material. Darwin later marked references to birds on either side with vertical lines ||. It has been our aim to make Darwin's notebooks widely accessible and readable, as well as a scholarly edition.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the field notebooks are quite different from all of Darwin's other notebooks, except the Glen Roy field notebook of 1838 (DAR 118), in that they all contain diagrams or sketches. With the exception of a small number of apparently meaningless cross-hatches and doodles, we include photographs of all of these drawings in the transcriptions (in the print volume). To assist the reader the writing contained in these drawings is also transcribed and the sketches turned to the horizontal when necessary. We have provided captions to those that have been identified and which are not already captioned by Darwin or which do not appear to be self explanatory. Some of the notebooks, notably St. Fe , are abundantly illustrated with geological sections which Darwin was able later to 'stitch together', via various intermediate copies, now preserved in the Darwin Archive at Cambridge University Library, into the versions he published in the three works which comprised his Geology of the Beagle . Of at least equal interest are the far fewer but equally informative sketches of animals, apparently in some cases having been dissected, and the occasional crude diagram of human interest, such as the floor plan of a house, a tiny drawing of the Beagle , and a self-portrait of Darwin as a 'stick man' on the cliffs of St Helena.

With one partial exception, Darwin did not number the pages of the notebooks, and often wrote in them at different times from opposite ends. This edition therefore uses an 'a, b' page numbering system. When a notebook was used starting from opposite ends the pages written from the front cover are labelled 'a', and pages written from the back cover are labelled 'b'. In order to make the transcriptions readable the second sequence, starting with the back cover, is placed immediately after the end of the first sequence. With the original manuscript it is necessary to turn the notebook around and begin reading from the other end. Most of the notebooks have brass clasps and we use the convention of referring to the cover with the hinge attached as the back cover.

Many persons, places and publications are recorded in the notebooks which appear in no other Darwin manuscripts. To make the notebooks more accessible explanatory footnotes are provided. The notes identify persons referred to in the text and references to publications as well as technical terms or particular specimens when these could be readily identified in Darwin's other Beagle records. By consulting the first occurrence of technical terms and so forth, the index can be used as a glossary. The definitions are mostly intended for the general reader.

Naturally, entries tend to be telegraphic in style and (as is normal in field notebooks, with the spine parallel to the lines of writing), the lines are often only a few words long. In the transcriptions presented here line breaks are ignored to aid readability, except where it is clear that a new sentence or topic is introduced.

Summarising the content of the notebooks in a few paragraphs would not only be impossible, but also rather pointless since we already have Barlow's 1945 unsurpassably engaging précis. Even Barlow at times had to admit defeat in trying to convey an impression of the hundreds of pages of geological descriptions, diagrams and speculations which fill great swathes of the notebooks, especially those used during 1834 and 1835. A series of quotes, in more or less chronological order, at least proves the potential of the notebooks:

'Solitude on board enervating heat comfort hard to look forward pleasures in prospect do not wish for cold night [delicious] sea calm sky not blue' [ Cape de Verds notebook , p. 46b] 'View at first leaving Rio sublime & picturesque intense colours blue prevailing tint large plantations of sugar & rustling coffee: mimosa natural veil' [ Rio notebook , p. 2a] 'Always think of home' [ Buenos Ayres notebook , p. 4b] 'The gauchos …look as if they would cut your throat and make a bow at the same time' [ Falkland notebook , p. 34a] 'Nobody knows pleasure of reading till a few days of such indolence' [ B. Blanca notebook , p. 12a] 'Most magnificently splendid the view of the mountains' [ Valparaiso notebook , p. 78a] 'Scenery very interesting – Had often wondered how Tierra del F would appear if elevated' [ Santiago notebook , p. 35a] 'Rode down to Port, miserable rocky desert. –' [ Copiapò notebook , p. 14a] 'But everything exceeded by ladies, like mermaids; could not keep eyes away from them' [ Galapagos notebook , p. 18a]

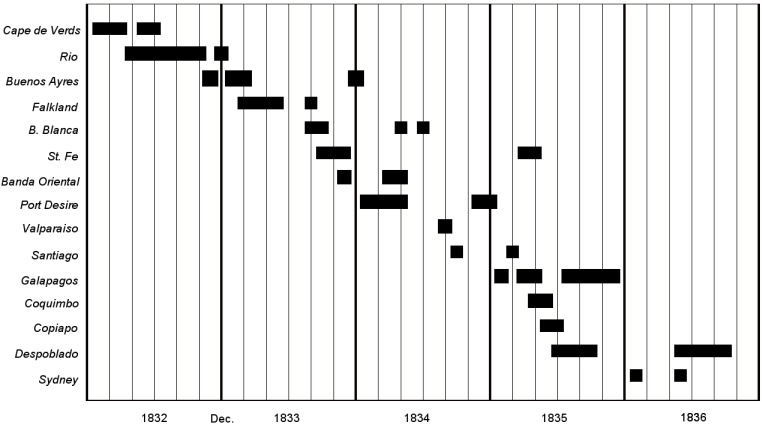

The following diagram attempts to show the periods of time over which Darwin used the notebooks during the voyage. Several of the notebooks were used at different times, and sometimes more than one notebook was in use at any one time, so that the relationships between the notebooks are sometimes quite complex. We should stress that this diagram only shows that a notebook was used in any particular month. The text of the notebooks need to be consulted to see whether this was many pages of continuous use, or a few dateable jottings.

The notebooks are of variable length. The total length of all fifteen previously unpublished field notebooks is 116,000 words. There are a small number of entries (mainly notes and drawings) which, although contemporary, are not in Darwin's hand.

It is possible to give some general impressions of how Darwin's use of the notebooks gradually shifted throughout the voyage. There is a symmetry to the use of the notebooks in that their use gradually built up during the first year of the voyage, reached a plateau in the middle years, them tailed off in the last year. The first three notebooks gradually get longer, then there is a big 'jump up' to the Falklands notebook which is not only almost twice as long as its predecessors but for the first time is routinely used for lengthy description. Darwin maintained this 'Falklands' style of use through the three 'South American' years of the voyage, but it 'spiked' quite extraordinarily in the St Fe notebook of which the bulk dates from early 1835. The daily rate of note-taking starts to drop off noticeably after Darwin left South America. St Fe is seven times longer than the two shortest notebooks, which are those used at the beginning and end of the voyage.

The Santiago notebook was being used at the same time as St Fe and seems to mark a new development in Darwin's note-taking. In Santiago for the first time he started to split off his theoretical notes from his more observational notes and kept Santiago for theory until it was 'joined' by the exclusively theoretical Red notebook in May 1836. This is a new interpretation of Santiago and R.N. as previous scholars have assumed not only that use of Santiago ceased when R.N. started, but that the transition from field notes to theory notes is to be seen in R. N. whereas we believe it is in Santiago.

We present the notebooks here in their entirety for the first time and for each notebook we have provided an individual introduction. These introductions are intended to assist the general reader to understand more fully than may be possible just from the notebook texts what exactly Darwin was doing in any particular place or on any particular date. To make it easy to compare the notebook entries with other Darwin manuscripts, such as for example his Beagle diary or correspondence, we always use the place names he used. In cases where this differs from the present-day name, on first mention we provide the present day place name in square brackets.

As the Beagle diary and Correspondence are more lengthy documents which overlap, chronologically, with the notebooks, it is necessary frequently to consult both when using the Beagle notebooks. Citing the Beagle diary and Correspondence on every date in the notebooks would be too cumbersome. Reference should also be made to the other published Beagle manuscripts, such as the Zoology notes .

Although there can be no substitute for reading the notebooks themselves, we hope that the introductions if read in sequence would give the general reader a good idea of Darwin's scientific development during the voyage. To this end we have used the earlier introductions to 'set the scene' and to introduce the key scientific issues facing Darwin and his mentors back in England. As the voyage progresses the introductions go into more and more detail as Darwin climbs metaphorically and actually into higher and higher realms of geology.

While the notebooks are overwhelmingly geological they also record Darwin's field work in botany and zoology ('natural history') and his observations in those fields which came to dominate Darwin's scientific career after the voyage. We have, therefore, devoted perhaps disproportionate attention to 'natural history' as the introductions move forward in time. In particular, we discuss Darwin's gradual accumulation of evidence that something was wrong with received wisdom concerning the 'death' and more dramatically the 'birth' of species, even when this evidence is only scrappily recorded in the notebooks. This discussion culminates with Darwin's realisation in the Galapagos notebook that the land birds there are American, implying an historical origin on the mainland rather than a special local creation to suit volcanic island conditions. Our final introduction reflects on Darwin's apparent loss of belief in the Creator's role in nature, triggered by watching a humble ant-lion catching its prey, an event not mentioned in the Sydney notebook .

The notebooks contain over 300 sketches and doodles. These are indicated in the online transcriptions with editorial notes. As English Heritage plans to publish images of the notebooks on their website in 2009 Darwin Online was not given permission to reproduce microfilm or other images of the notebooks apart from the missing Galapagos notebook .

We are grateful to English Heritage, and to the curators of Down House, Tori Reeve and Cathy Power, for allowing us to access and publish online transcriptions of the notebooks.

Gordon Chancellor, John van Wyhe and Kees Rookmaaker

September 2007

See also the Chronological register to the notebooks and Concordance to Darwin's Beagle diaries and notebooks .

The beagle field notebooks:.

Cape de Verds notebook (1-6.1832). Introduction Text EH 88202324

Rio notebook (4.1832, 6.1832-10.1832). Introduction Text EH88202330

Buenos Ayres notebook (11-12.1832-2.1833; 12.1833). Introduction Text EH88202332

Falkland notebook (2-5.1833; 8.1833). Introduction Text EH88202334

B. Blanca notebook (9-10.1833). Introduction Text EH88202331

St. Fe notebook (9-11.1833; 3-4.1835). Introduction Text EH88202333

Banda Oriental notebook (11.1833, 4-5.1834). Introduction Text EH88202329

Port Desire notebook (1-4.1834, 11-12.1834) . Introduction Text EH88202328

Valparaiso notebook (8.1834). Introduction Text EH88202335

Santiago notebook (9.1834; 2.1835-9.1838?). Introduction Text EH88202338

Galapagos notebook (1835). Introduction Text Image Text & image EH88202337 See also the extensive introduction to the Galapagos pages by Chancellor and Keynes.

Coquimbo notebook (4-5.1835). Introduction Text EH88202336

Copiapò notebook (6.1835). Introduction Text EH88202327

Despoblado notebook (6-9.1835; 5-9.1836). Introduction Text EH88202326

Sydney notebook (1-4.1836). Introduction Text EH88202323

File last up 18 October, 2024 e -->e -->

An Interview with Charles Darwin

Marissa Shapiro

Oct 16, 2024, 11:30 AM

The intrepid CEO of The Protein Society, Raluca Cadar, again used her special Carpathian “connections” to set up our Annual TPS Halloween interview, this year with none other than Charles Darwin. We listen in on his conversation with Basic Sciences Vice Dean Chuck Sanders …

Chuck Sanders: Mr. Darwin, words cannot express what an honor it is to meet you. Thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts on proteins and other topics with us!

Charles Darwin: From one Charles to another, I am pleased to meet you. During my time in the Land of the Living, we knew that proteins existed and were important for life, but the series of key discoveries underlying their true importance and how they are related to the Central Dogma was still many years away. It is only much later—here in the land of What Comes Next—that I have come to appreciate the profound role of proteins in life and the mechanisms driving evolution. It is great that this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes both the importance of proteins and the fact that their study remains a frontier area of science.

Sanders : Thanks for saying so! It is notable that while you were collecting the massive trove of data leading the theory of natural selection presented in The Origin of the Species, Gregor Mendel was in his garden in Moravia conducting experiments with pea plants that started the field of genetics. But you did not know about him and his work during your lifetime, did you?

Darwin: Sadly, no. So, all I could do was speculate about the fundamental mechanisms driving natural selection. But Greg and I are now friends; we shoot pool together.

Sanders: Raluca tells me I am not allowed to ask any questions about What Comes Next, so I can’t follow up on this interesting revelation. But let me ask you about your work on barnacles. My understanding is that after you completed the Voyage of the Beagle you spent seven years characterizing barnacles. One of your biographers, Janet Browne , has suggested that it was this very systematic and detailed study that provided you with the intellectual tools to go on to analyze the trove of data that led to an airtight case for evolution. Since your barnacle work largely involved morphological measurements of how one type of barnacle differs from another, I have long thought that you might be able to claim the title of the first structural biologist.

Darwin: What I would have given for a cryo-electron microscope! But this is a good example of “familiarity breeds contempt.” I hate barnacles. Let’s change the subject.

Sanders: So much of your career was inspired by your experience as the appointed naturalist on the five-year voyage of the HMS Beagle , starting when you were only 22 years old. There is another famous beagle in the history of exploration. The lunar lander of the Apollo 10 mission (the final test flight before the moon landing) was named Snoopy, after Charlie Brown’s pet beagle. I’ve long wondered whether the NASA folks intentionally made the connection with the HMS Beagle or whether this was just serendipity. Anyway, I digress. I understand that all through your voyage, you suffered badly from seasickness, right? I’ve been seasick before—you don’t die, but you wish you were dead! I just can’t imagine enduring that for nearly five years!

Darwin: As you moderns say, no pain no gain! Actually, the silver lining is that, because of seasickness, when the Beagle sailed from Brazil to Peru, Captain FitzRoy let me cover much of this route on land, hiking or riding by horse from port to port while the rest of the crew sailed. The exploration of South America and the observations I made there turned out to be absolutely critical to my development as a scientist—amazing geology, flora, fauna, fossils… South America had it all in abundance!

Sanders : It does sound like an amazing adventure. My idea of an adventure is hiking the perimeter of the local golf course!

Darwin : Lions and tigers and bears, oh my!

Sanders : On a profoundly more serious note, while slavery was already outlawed in Britain, you encountered its lingering practice in Brazil, right?

Darwin: My forebears were vocal abolitionists back in the day when slavery was still active in England. Also, my excellent taxidermy tutor was John Edmondstone, a freedman. However, nothing had prepared me for the horror of what I encountered in Brazil and other parts of South America.

Sanders: Particularly in light of this, it is an amazing coincidence in history that you and Abraham Lincoln were born on the same February day in 1809!

Darwin : Yes, Abe is also one of my pool buddies.

Sanders : Wow… Back to the voyage. The Beagle eventually sailed to Australia, where they later named both Port Darwin and the city of Darwin after you. You must be very proud of that!

Darwin: Well yes, I am. However, it was not always that way. Back in the day, an association with Australia was not something a British gentleman welcomed! Thankfully, times have changed, and I am especially thrilled about all of the fantastic science going on Down Under.

Sanders: I have been there, and I can attest to that! I especially would encourage anyone with an interest in proteins to someday coordinate travel to Australia with a visit to the annual Lorne Proteins Conference , not far from Melbourne. Should be on everyone’s bucket list! The Protein Society has a wonderful speaker exchange program with the Lorne folks. Changing the subject again, I find it very amusing that when you were young and trying to decide whether to propose to Emma Wedgewood, you made a list of advantages and disadvantages to marriage. One of the advantages you listed, and I quote, is: “Constant companion and friend in old age… better than a dog anyhow.”

Darwin: That was when I was a young and unenlightened man. Please do note that “better than a dog” was actually a high compliment, coming from me. I love dogs.

Sanders: It is interesting that as a young man you went on that grand voyage, but when you settled down and took up residence with Emma at Down House, you sort of became hobbit-like in avoiding travel.

Darwin: Emma and I had a lot of work to do there at Down House! We raised a large family (including dealing with the loss of three children), and it’s also where I did my barnacles work and later wrote On the Origin of Species . Plus, I was often not feeling very well. I now realize that I almost certainly picked up a parasite or two during the voyage.

Sanders: Your final project was the earthworms project, which led to the book that was your best seller during your lifetime and is still considered an important work in vermeology. The beauty of the project is that your backyard was your laboratory. You apparently had your whole family, including grandchildren enlisted.

Darwin: Yes, what fun it was! The grandeur of life on Earth, even right under our noses, is unbounded!

Sanders: I want to ask you about a story I first heard from an Emma Stone skit on Saturday Live . The story is that you had a pet tortoise, Harriet, and that it lived until just a few years ago and was owned for a while by the Australian TV zoologist, Steve Irwin. True?

Darwin: Hmmm… we did indeed collect several juvenile tortoises from the Galapagos Islands in 1835 and returned them to Britain on the Beagle . However, they were turned over to zoos and museums. I heard rumors that one of the later captains of the Beagle eventually transported one of them to Australia. It is very possible that it later became Mr. Irwin’s pet. These amazing creatures live up to 200 years old! If I see Steve, I will ask him about Harriet.

Sanders: The popular press was pretty rough on you during your lifetime. Was that hard?

Darwin: Yes. But this is where it was good to be anchored by my family at home in Down House. It was a shelter in a time of storm, to borrow a line from an old hymn.

Sanders: My own favorite reference to you in popular culture is a call-out in the R.E.M. song “Man in the Moon.” It salutes your courage as a scientist to pursue the truth even though the implications of the truth were viewed as a threat to long-established societal beliefs about the nature of life.

Darwin: I do know the song, but appreciate that you can’t quote the exact lyrics in polite company! I definitely was not interested in upsetting societal norms, but to misquote Jesus: truth is like the wind—it blows where it will.

Sanders: One last question: If you were invited to a Halloween party, what would you dress up as?

Darwin: That’s easy! I would go as Charlie the Octopus. I always thought that octopi are wondrous creatures and we now know that not only are they very intelligent, they have a nervous system that is set up completely differently than in most animals. A large fraction of octopus neurons are distributed in their tentacles.

Sanders: I would love to see you as an octopus. But I never get invited to the good parties! Alas! It is time to close. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat, I am very grateful!

Darwin : Not at all. Please pass on my regards to your colleagues. Keep up the good work!

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Becky Sanders and Raluca Cadar for their edits. If you would like to learn more about Charles Darwin and the development of the theory of natural selection and evolution I highly recommend Janet Browne’s magnificent two-volume biography Voyaging and The Power of Place . A slightly modified version of this interview is also published in the October 2024 Protein Society Newsletter, Under the Microscope .

Explore Story Topics

- Uncategorized

- Chuck Sanders

- School of Medicine Basic Sciences

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

this activity, you'll learn how to interpret images and maps in order to extract information about Darwin's trip to the Galapagos Islands. Process. Look at material in the . Voyage of the Beagle Gallery. and answer a few questions. First, examine the images and read the captions of these slides: Route of the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin ...

Procedure Part A: Putting Darwin on the Map 1. Print the world map (pdf) and excerpts from Darwin's The Voyage of the Beagle (pdf).Each journal excerpt describes a location and includes a date and ...

The Beagle arrived here on the 24th of August, and a week afterwards sailed for the Plata. With Captain Fitz Roy's consent I was left behind, to travel by land to Buenos Ayres. I will here add some observations, which were made during this visit and on a previous occasion, when the Beagle was employed in surveying the harbour.

This fact a day page is about the famous Voyage of the HMS Beagle which carried Charles Darwin around the world and to Cape Town. It also includes a report writing activity. Teacher Note - Please check the content in the QR code link, including any comments, is suitable for your educational environment before showing. Please do not let the next video automatically play at the end of the clip ...

Activity 1 Teacher Notes: Darwin's Great Voyage of Discovery: Students learn about Darwin's voyage on the Beagle by reading excerpts from his letters and journals and mapping his route. Instead of ...

The Voyage Of The Beagle Worksheet Charles Darwin,E. J. Browne,Michael Neve. ... The Voyage of the Beagle Charles Darwin,2017-02-17 The Voyage of the Beagle is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his Journal and Remarks bringing him considerable fame and respect This was the third volume

About This Quiz & Worksheet. The questions on these assessments will check your knowledge of the events delineated in The Voyage of the Beagle.You must also know how Darwin ended up on the expedition.

Charles Darwin set sail on the ship HMS Beagle on December 27, 1831, from Plymouth, England. Darwin was 22 years old when he was hired to be the ship's naturalist. Most of the trip was spent sailing around South America. There Darwin spent considerable time ashore collecting plants and animals.

This fact a day page is about the famous Voyage of the HMS Beagle which carried Charles Darwin around the world and to Cape Town. It also includes a report writing activity. Teacher Note - Please check the content in the QR code link, including any comments, is suitable for your educational environment before showing. Please do not let the next video automatically play at the end of the clip ...

A complete lesson with the LO: to understand Darwin's voyage on HMS Beagle. During the lesson, students will map the voyage and key events on each stop of the journey. All resources are included, although internet access may be required for the higher attainers to research additional information, using the Beagle diaries (Link included in the ...

"The Voyage of the Beagle" by Charles Darwin is a scientific expedition journal written in the early 19th century. This work recounts Darwin's travels and observations during his time aboard the HMS Beagle, focusing on natural history and geology as he sails through various parts of South America and adjacent islands.

A book by Charles Darwin based on his notes from the second survey expedition of HMS Beagle from 1831 to 1836. The book covers his observations on biology, geology, and anthropology, and hints at his evolving ideas on evolution.

Working in pairs or small groups, you'll look at material in the Voyage of the Beagle Gallery and answer a few questions. First, examine the images and read the captions of these slides: Route of the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin, Tierra del Fuego, and Galapagos Islands.

Charles Darwin Facts & Worksheets Charles Darwin facts and information plus worksheet packs and fact file. Includes 5 activities aimed at students 11-14 years old (KS3) & 5 activities aimed at students 14-16 years old (GCSE). ... Voyage of the Beagle. Darwin was offered a position as a naturalist on HMS Beagle, one of the British Royal Navy ...

Learn about the five-year journey of Charles Darwin aboard the Royal Navy ship H.M.S. Beagle, from 1831 to 1836. Explore the places he visited, the specimens he collected, and the insights he gained that influenced his theory of evolution.

Learn how the naturalist Charles Darwin explored South America and the Pacific Ocean on board the HMS Beagle, and how his observations shaped his theory of evolution. Discover his encounters with nature, culture, and geology, and his discoveries of fossils, animals, and plants.

HMS Beagle set sail on her voyage in 1831. Living conditions on the ship were hard at times. There was not a lot of room on board as the ship held 75 people. Darwin was often seasick and also caught a fever. The Beagle's voyage lasted for five years. They travelled to South America and reached the Galapagos Islands. When he went ashore, Darwin ...

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website. If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

Charles Darwin's notebooks from the voyage of the Beagle. [Foreword by Richard Darwin Keynes]. Cambridge: University Press, 2009. [656pp. with over 300 illustrations and 1000 notes.] There are three other notebooks at Down House which do not seem to have been used in the field during the Beagle voyage and therefore are not included in this edition.

Charles Darwin, serenely composed in anticipation of the Voyage of the Beagle. The intrepid CEO of The Protein Society, Raluca Cadar, again used her special Carpathian "connections" to set up our Annual TPS Halloween interview, this year with none other than Charles Darwin. We listen in on his conversation with