Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

The treatment and prevention of travelers' diarrhea are discussed here. The epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of travelers' diarrhea are discussed separately. (See "Travelers' diarrhea: Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis" .)

Clinical approach — Management of travelers’ diarrhea depends on the severity of illness. Fluid replacement is an essential component of treatment for all cases of travelers’ diarrhea. Most cases are self-limited and resolve on their own within three to five days of treatment with fluid replacement only. Antimotility agents can provide symptomatic relief but should not be used when bloody diarrhea is present. Antimicrobial therapy shortens the disease duration, but the benefit of antibiotics must be weighed against potential risks, including adverse effects and selection for resistant bacteria. These issues are discussed in the sections that follow.

When to seek care — Travelers from resource-rich settings who develop diarrhea while traveling to resource-limited settings generally can treat themselves rather than seek medical advice while traveling. However, medical evaluation may be warranted in patients who develop high fever, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, or vomiting. Otherwise, for most patients while traveling or after returning home, medical consultation is generally not warranted unless symptoms persist for 10 to 14 days.

Fluid replacement — The primary and most important treatment of travelers' (or any other) diarrhea is fluid replacement, since the most significant complication of diarrhea is volume depletion [ 11,12 ]. The approach to fluid replacement depends on the severity of the diarrhea and volume depletion. Travelers can use the amount of urine passed as a general guide to their level of volume depletion. If they are urinating regularly, even if the color is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely mild. If there is a paucity of urine and that small amount is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely more severe.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

Travelers' Diarrhea

Español

Travelers' diarrhea is the most common travel-related illness. It can occur anywhere, but the highest-risk destinations are in Asia (except for Japan and South Korea) as well as the Middle East, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America.

In otherwise healthy adults, diarrhea is rarely serious or life-threatening, but it can make a trip very unpleasant.

You can take steps to avoid travelers’ diarrhea

- Choose food and drinks carefully Eat only foods that are cooked and served hot. Avoid food that has been sitting on a buffet. Eat raw fruits and vegetables only if you have washed them in clean water or peeled them. Only drink beverages from factory-sealed containers, and avoid ice because it may have been made from unclean water.

- Wash your hands Wash your hands often with soap and water, especially after using the bathroom and before eating. If soap and water aren’t available, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer. In general, it’s a good idea to keep your hands away from your mouth.

Learn some ways to treat travelers’ diarrhea

- Drink lots of fluids If you get diarrhea, drink lots of fluids to stay hydrated. In serious cases of travelers’ diarrhea, oral rehydration solution—available online or in pharmacies in developing countries—can be used for fluid replacements.

- Take over-the-counter drugs Several drugs, such as loperamide, can be bought over-the-counter to treat the symptoms of diarrhea. These drugs decrease the frequency and urgency of needing to use the bathroom, and may make it easier for you to ride on a bus or airplane while waiting for an antibiotic to take effect.

- Only take antibiotics if needed Your doctor may give you antibiotics to treat travelers’ diarrhea, but consider using them only for severe cases. If you take antibiotics, take them exactly as your doctor instructs. If severe diarrhea develops soon after you return from your trip, see a doctor and ask for stool tests so you can find out which antibiotic will work for you.

More Information

- Travelers’ Diarrhea- CDC Yellow Book

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Traveler's diarrhea

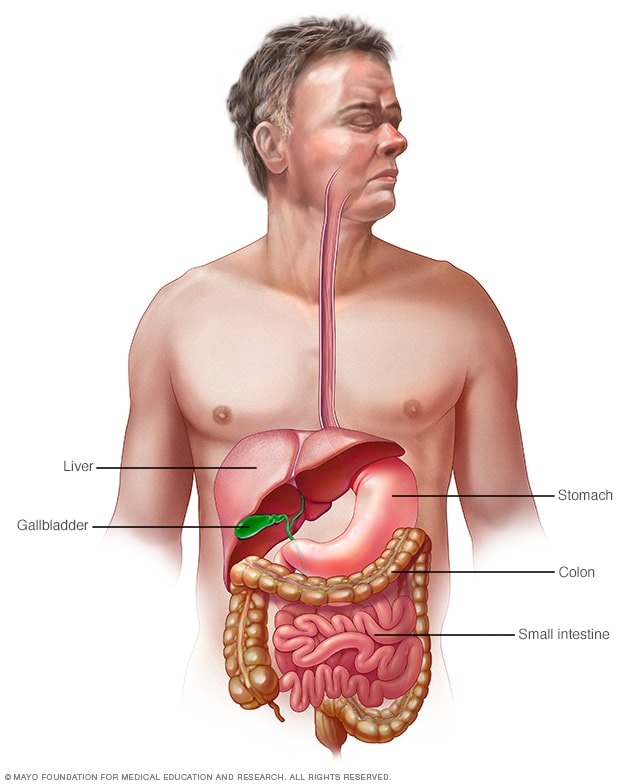

Gastrointestinal tract

Your digestive tract stretches from your mouth to your anus. It includes the organs necessary to digest food, absorb nutrients and process waste.

Traveler's diarrhea is a digestive tract disorder that commonly causes loose stools and stomach cramps. It's caused by eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea usually isn't serious in most people — it's just unpleasant.

When you visit a place where the climate or sanitary practices are different from yours at home, you have an increased risk of developing traveler's diarrhea.

To reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea, be careful about what you eat and drink while traveling. If you do develop traveler's diarrhea, chances are it will go away without treatment. However, it's a good idea to have doctor-approved medicines with you when you travel to high-risk areas. This way, you'll be prepared in case diarrhea gets severe or won't go away.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

Traveler's diarrhea may begin suddenly during your trip or shortly after you return home. Most people improve within 1 to 2 days without treatment and recover completely within a week. However, you can have multiple episodes of traveler's diarrhea during one trip.

The most common symptoms of traveler's diarrhea are:

- Suddenly passing three or more looser watery stools a day.

- An urgent need to pass stool.

- Stomach cramps.

Sometimes, people experience moderate to severe dehydration, ongoing vomiting, a high fever, bloody stools, or severe pain in the belly or rectum. If you or your child experiences any of these symptoms or if the diarrhea lasts longer than a few days, it's time to see a health care professional.

When to see a doctor

Traveler's diarrhea usually goes away on its own within several days. Symptoms may last longer and be more severe if it's caused by certain bacteria or parasites. In such cases, you may need prescription medicines to help you get better.

If you're an adult, see your doctor if:

- Your diarrhea lasts beyond two days.

- You become dehydrated.

- You have severe stomach or rectal pain.

- You have bloody or black stools.

- You have a fever above 102 F (39 C).

While traveling internationally, a local embassy or consulate may be able to help you find a well-regarded medical professional who speaks your language.

Be especially cautious with children because traveler's diarrhea can cause severe dehydration in a short time. Call a doctor if your child is sick and has any of the following symptoms:

- Ongoing vomiting.

- A fever of 102 F (39 C) or more.

- Bloody stools or severe diarrhea.

- Dry mouth or crying without tears.

- Signs of being unusually sleepy, drowsy or unresponsive.

- Decreased volume of urine, including fewer wet diapers in infants.

It's possible that traveler's diarrhea may stem from the stress of traveling or a change in diet. But usually infectious agents — such as bacteria, viruses or parasites — are to blame. You typically develop traveler's diarrhea after ingesting food or water contaminated with organisms from feces.

So why aren't natives of high-risk countries affected in the same way? Often their bodies have become used to the bacteria and have developed immunity to them.

Risk factors

Each year millions of international travelers experience traveler's diarrhea. High-risk destinations for traveler's diarrhea include areas of:

- Central America.

- South America.

- South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Traveling to Eastern Europe, South Africa, Central and East Asia, the Middle East, and a few Caribbean islands also poses some risk. However, your risk of traveler's diarrhea is generally low in Northern and Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Your chances of getting traveler's diarrhea are mostly determined by your destination. But certain groups of people have a greater risk of developing the condition. These include:

- Young adults. The condition is slightly more common in young adult tourists. Though the reasons why aren't clear, it's possible that young adults lack acquired immunity. They may also be more adventurous than older people in their travels and dietary choices, or they may be less careful about avoiding contaminated foods.

- People with weakened immune systems. A weakened immune system due to an underlying illness or immune-suppressing medicines such as corticosteroids increases risk of infections.

- People with diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe kidney, liver or heart disease. These conditions can leave you more prone to infection or increase your risk of a more-severe infection.

- People who take acid blockers or antacids. Acid in the stomach tends to destroy organisms, so a reduction in stomach acid may leave more opportunity for bacterial survival.

- People who travel during certain seasons. The risk of traveler's diarrhea varies by season in certain parts of the world. For example, risk is highest in South Asia during the hot months just before the monsoons.

Complications

Because you lose vital fluids, salts and minerals during a bout with traveler's diarrhea, you may become dehydrated, especially during the summer months. Dehydration is especially dangerous for children, older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

Dehydration caused by diarrhea can cause serious complications, including organ damage, shock or coma. Symptoms of dehydration include a very dry mouth, intense thirst, little or no urination, dizziness, or extreme weakness.

Watch what you eat

The general rule of thumb when traveling to another country is this: Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it. But it's still possible to get sick even if you follow these rules.

Other tips that may help decrease your risk of getting sick include:

- Don't consume food from street vendors.

- Don't consume unpasteurized milk and dairy products, including ice cream.

- Don't eat raw or undercooked meat, fish and shellfish.

- Don't eat moist food at room temperature, such as sauces and buffet offerings.

- Eat foods that are well cooked and served hot.

- Stick to fruits and vegetables that you can peel yourself, such as bananas, oranges and avocados. Stay away from salads and from fruits you can't peel, such as grapes and berries.

- Be aware that alcohol in a drink won't keep you safe from contaminated water or ice.

Don't drink the water

When visiting high-risk areas, keep the following tips in mind:

- Don't drink unsterilized water — from tap, well or stream. If you need to consume local water, boil it for three minutes. Let the water cool naturally and store it in a clean covered container.

- Don't use locally made ice cubes or drink mixed fruit juices made with tap water.

- Beware of sliced fruit that may have been washed in contaminated water.

- Use bottled or boiled water to mix baby formula.

- Order hot beverages, such as coffee or tea, and make sure they're steaming hot.

- Feel free to drink canned or bottled drinks in their original containers — including water, carbonated beverages, beer or wine — as long as you break the seals on the containers yourself. Wipe off any can or bottle before drinking or pouring.

- Use bottled water to brush your teeth.

- Don't swim in water that may be contaminated.

- Keep your mouth closed while showering.

If it's not possible to buy bottled water or boil your water, bring some means to purify water. Consider a water-filter pump with a microstrainer filter that can filter out small microorganisms.

You also can chemically disinfect water with iodine or chlorine. Iodine tends to be more effective, but is best reserved for short trips, as too much iodine can be harmful to your system. You can purchase water-disinfecting tablets containing chlorine, iodine tablets or crystals, or other disinfecting agents at camping stores and pharmacies. Be sure to follow the directions on the package.

Follow additional tips

Here are other ways to reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea:

- Make sure dishes and utensils are clean and dry before using them.

- Wash your hands often and always before eating. If washing isn't possible, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol to clean your hands before eating.

- Seek out food items that require little handling in preparation.

- Keep children from putting things — including their dirty hands — in their mouths. If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Tie a colored ribbon around the bathroom faucet to remind you not to drink — or brush your teeth with — tap water.

Other preventive measures

Public health experts generally don't recommend taking antibiotics to prevent traveler's diarrhea, because doing so can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotics provide no protection against viruses and parasites, but they can give travelers a false sense of security about the risks of consuming local foods and beverages. They also can cause unpleasant side effects, such as skin rashes, skin reactions to the sun and vaginal yeast infections.

As a preventive measure, some doctors suggest taking bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease the likelihood of diarrhea. However, don't take this medicine for longer than three weeks, and don't take it at all if you're pregnant or allergic to aspirin. Talk to your doctor before taking bismuth subsalicylate if you're taking certain medicines, such as anticoagulants.

Common harmless side effects of bismuth subsalicylate include a black-colored tongue and dark stools. In some cases, it can cause constipation, nausea and, rarely, ringing in your ears, called tinnitus.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Infectious enteritis and proctocolitis. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Microbiology, epidemiology, and prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Traveler diarrhea. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Diarrhea. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diarrhea. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Travelers' diarrhea. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Khanna S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 29, 2021.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

We’re transforming healthcare

Make a gift now and help create new and better solutions for more than 1.3 million patients who turn to Mayo Clinic each year.

When viewing this topic in a different language, you may notice some differences in the way the content is structured, but it still reflects the latest evidence-based guidance.

Traveller's diarrhoea

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

Traveller's diarrhoea is a common problem among travellers to destinations with deficiencies in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, typically caused by the consumption of contaminated food or water. Predominantly caused by bacteria.

Prevention strategies include careful selection of food and beverages, though these are not fail-safe. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for most travellers.

Management is self-diagnosis while still travelling, followed by hydration, medicine for symptom relief, and possibly, antibiotics. Antibiotic therapy is generally reserved for moderate to severe infections.

In healthy patients, resolution is typically within 3-5 days even without antibiotic treatment.

Traveller's diarrhoea (TD) is defined as ≥3 unformed stools in 24 hours accompanied by at least one of the following: fever, nausea, vomiting, cramps, tenesmus, or bloody stools (dysentery) during a trip abroad, typically to a destination with deficiencies in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure. It is usually a benign, self-limited illness lasting 3-5 days.

History and exam

Key diagnostic factors.

- presence of risk factors

- diarrhoea (with or without tenesmus), cramping, nausea, and vomiting

- dysentery (blood and fever)

- persistent diarrhoea >14 days

Other diagnostic factors

- diarrhoea without illness

Risk factors

- travel to a high-risk destination

- age <30 years

- proton-pump inhibitor use

- travellers with prior residence in higher-risk destination visiting friends and relatives

- travel during hot and wet seasons

- deployed military populations

- lack of caution in food and water selection

Diagnostic investigations

1st investigations to order.

- stool culture and sensitivity

- multi-pathogen molecular diagnostic (polymerase chain reaction)

- protozoal stool antigens

Investigations to consider

- stool ova and parasite examination

- Clostridioides difficile stool toxin

- colonoscopy, endoscopy, and biopsy

- haematology, blood chemistries, serology

Treatment algorithm

Pre-travel prophylaxis, non-pregnant adults: mild diarrhoea, non-pregnant adults: moderate diarrhoea, non-pregnant adults: severe diarrhoea, contributors, daniel t. leung, md, msc.

Associate Professor

Division of Infectious Diseases

University of Utah School of Medicine

Salt Lake City

Disclosures

DTL receives authorship royalties from UpToDate, Inc, for a chapter on travel medicine. DTL is an author of upcoming chapters on traveller's diarrhoea for the US CDC Yellow Book. DTL is the president-elect of the American Committee on Clinical Tropical Medicine and Travelers' Health - Clinical Group within the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. DTL is an author of some of the references cited in this topic.

Jakrapun Pupaibool, MD, MS

JP declares that he has no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Dr Daniel T. Leung and Dr Jakrapun Pupaibool would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Mark Riddle and Professor Gregory Juckett, the previous contributor to this topic.

MR has given talks on the management of traveller's diarrhoea for the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM), the CDC Foundation, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), and the American College of Preventive Medicine. MR has led the development of guidelines for traveller's diarrhea for the ISTM, the ACG, and the Department of Defense. This work has been unpaid but support for travel has been accepted. MR is employed with Pfizer Inc., and is working on their Lyme disease vaccine programme. While this is not in conflict with traveller’s diarrhoea, Pfizer also makes azithromycin, which is an antibiotic recommended for the treatment of traveller’s diarrhoea. MR does not work in the area of Pfizer that develops, markets, or distributes azithromycin. MR is an author of several references cited in this topic. GJ declares that he has no competing interests.

Peer reviewers

Andrea summer, md.

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics

Medical University of South Carolina

AS declares that she has no competing interests.

Phil Fischer, MD

Professor of Pediatrics

Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine

Mayo Clinic

PF is an author of a reference cited in this topic.

Differentials

- Food poisoning

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Secondary disaccharidase (or other dietary) deficiency

- CDC Yellow Book 2024: travelers' diarrhea

- 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of infectious diarrhea

Patient leaflets

Diarrhoea in adults

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer

Help us improve BMJ Best Practice

Please complete all fields.

I have some feedback on:

We will respond to all feedback.

For any urgent enquiries please contact our customer services team who are ready to help with any problems.

Phone: +44 (0) 207 111 1105

Email: [email protected]

Your feedback has been submitted successfully.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Travelers diarrhea.

Noel Dunn ; Chika N. Okafor .

Affiliations

Last Update: July 4, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Traveler's diarrhea is a common ailment in individuals traveling to resource-limited destinations overseas. It is estimated to affect nearly 40 to 60 percent of travelers and is the most common travel-associated condition. Bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections can cause symptoms, though bacterial sources represent the most frequent etiology. Although traveler's diarrhea is typically a benign, self-resolving condition, it can lead to dehydration and, in severe cases, significant complications. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of traveler's diarrhea and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance outcomes for affected patients.

- Identify the causes of traveler's diarrhea.

- Identify strategies to prevent traveler's diarrhea.

- Explain the management of traveler's diarrhea.

- Explain the importance of improving coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance care for patients affected by traveler's diarrhea.

- Introduction

Travelers’ diarrhea is a common ailment in persons traveling to resource-limited destinations overseas. Estimates indicate that it affects nearly 40% to 60% of travelers depending on the place they travel, and it is the most common travel-associated condition. Bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections can cause symptoms, though bacterial sources represent the most frequent etiology. While travelers’ diarrhea is typically a benign self-resolving condition, it can lead to dehydration and, in severe cases, significant complications. [1] [2] [3]

The most common bacterial cause is enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), with estimates that the bacteria is responsible for nearly 30% of cases. Other common bacterial causes of travelers’ diarrhea include Campylobacter jejuni , Shigella , and Salmonella species. Norovirus is the most common viral cause while rotavirus is another source of infection. Giardia intestinalis is the most common parasitic source while Cryptosporidium and Entamoeba histolytica can also cause travelers’ diarrhea. The most common cause of travelers’ diarrhea varies by region, though the source is rarely identified in less severe cases. [4] [5] [6]

Traveler's diarrhea can occur in both short and long term travelers; in general, there is no immunity against future attacks. Traveler's diarrhea appears to be most common in warmer climates, in areas of poor sanitation and lack of refrigeration. In addition, the lack of safe water and taking short cuts to preparing foods are also major risk factors. In areas where food handling education is provided, rates of traveler's diarrhea are low.

- Epidemiology

Estimates place the incidence of travelers’ diarrhea at 30% to 60% of travelers to resource-limited destinations. Incidence and causal agent vary by destination, with the highest incidence reported in sub-Saharan Africa. Other locations with high incidence include Latin America, the Middle East, and South Asia. Risk factors are typically related to poor hygiene in resource-limited areas. These include poor hygienic practices in food handling and preparation; lack of refrigeration due to inadequate electrical supply; and poor food storage practices. Additional modifiable risk factors include proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, recent antibiotic use, and unsafe sexual practices. Risk factors for severe complications are pregnancy, young or old age, travelers with underlying chronic gastrointestinal diseases, or people who are immunocompromised. [7] [8]

- Pathophysiology

Travelers’ diarrhea is most commonly spread by fecal-oral transmission of the causative organism, typically through consumption of contaminated food or water. The incubation period varies by causal agent, with viruses and bacteria ranging from 6 to 24 hours and intestinal parasites requiring 1 to 3 weeks before the onset of symptoms. The pathophysiology for travelers’ diarrhea differs by a causative agent but can be split into non-inflammatory or inflammatory pathways. Non-inflammatory agents cause a decrease in the absorptive abilities of the intestinal mucosa, thereby increasing the output of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Inflammatory agents on the other hand cause destruction of the intestinal mucosa either through cytotoxin release or direct invasion of the mucosa. The loss of mucosa surface again results in a decrease of absorption with a resultant increase in bowel movements. [9]

- History and Physical

The onset of symptoms will typically occur 1 to 2 weeks after arrival in a resource-limited destination, though travelers can develop symptoms throughout their stay or shortly after arrival. Travelers’ diarrhea is considered as three or more loose stools in 24 hours or a two-fold increase from baseline bowel habits. Diarrhea often occurs precipitously and is accompanied by abdominal cramping, fever, nausea, or vomiting. Patients should be asked about any blood in their stool, fevers, or any associated symptoms. A thorough travel history should be obtained including timeline and itinerary, diet and water consumption at their destination, illnesses in other travelers, and possible sexual exposures.

In most self-limited cases physical examination will show mild diffuse abdominal tender to palpation. Providers should assess for dehydration through skin turgor and capillary refill. In more severe cases patients may have severe abdominal pain, high fever, and evidence of hypovolemia (tachycardia, hypotension).

Laboratory investigation is typically not required in most cases. In patients with concerning features, such as with high fever, hematochezia, or tenesmus, stool studies can be obtained. Typical stool studies include stool culture, fecal leukocytes, and lactoferrin. The stool should be assessed for ova and parasites in patients with longer duration of symptoms. New multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screens are becoming available and provide quick analysis of multiple stool pathogens. These screens, however, are expensive, are not widely available, and may not change the clinical management of patients. [4]

Radiological studies are not required in most cases. Kidneys, ureters, and bladder x-ray can be obtained to assess for acute intra-abdominal pathology or look for evidence of perforation in severe cases. An abdominal CT can also be used to assess for intraabdominal pathology in severe cases.

- Treatment / Management

Travelers should be counseled on risk reduction before travel, including avoiding tap water & ice, frequent hand washing, avoiding leafy vegetables or fruit that isn’t peeled, and avoiding street food. Bismuth subsalicylate (two tabs 4 times a day) can be used for prophylaxis and can reduce the incidence of travelers’ diarrhea by almost half, though it should be avoided in children and pregnant women due salicylate side effects. In short high-stakes travel, it may be reasonable to start antibiotics as prophylaxis but is generally avoided in longer-term travel. Rifaximin is a commonly used chemoprophylaxis due to its minimal absorption and minimal side effects. [10] [11] [12]

The foundation of diarrhea management is fluid repletion. In mild cases, travelers should focus on increasing water intake. Water is usually sufficient though sports drinks and other electrolyte fluids can be used. Pedialyte can be used for pediatric patients. Milk and juices should be avoided as this can worsen diarrhea. In more severe cases, oral rehydration salt can be used to ensure rehydration with adequate electrolyte repletion. In cases of severe dehydration, IV fluids may ultimately be required.

Treatment is supportive in mild-moderate cases. In patients without signs of inflammatory diarrhea, loperamide can be used for symptomatic relief. The typical dose for adults is 4 mg initially with 2 mg after each subsequent loose stool, not to exceed 16 mg total in a day.

Also, travelers can be given antibiotics to take as needed at the onset of symptoms. Ciprofloxacin is commonly used for treatment, though there are concerns with resistance with Campylobacter species. For this reason, fluoroquinolones are not often prescribed for travelers to Asia and azithromycin preferable. Also, azithromycin is often prescribed for pregnant travelers and children. A common regimen is 500 mg daily for three days, though evidence suggests that a single dose of 1000 mg may be slightly more effective. Parents can be given azithromycin powder with instructions to mix with water when needed. Rifaximin is a minimally absorbed antibiotic that is also available and is safe for older children and pregnant travelers.

- Differential Diagnosis

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Ischemic colitis

- Radiation-induced colitis

- Food poisoning

New Guidelines for Traveler's Diarrhea

- Travelers should be advised against the use of prophylactic antibiotics

- In high-risk groups, one may consider antibiotic prophylaxis

- Bismuth subsalicylate can be considered in any traveler.

- The antibiotic of choice is rifaximin

- Fluoroquinolones should not be used as prophylaxis

The outcomes in most patients with traveler's diarrhea are good. However, in severe cases, dehydration can occur requiring admission.

- Complications

- Dehydration

- Malabsorption

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Reactive arthritides

- Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The majority of patients are managed as outpatients and need to do the following:

- Maintain hydration

- Hand washing

- Only take antimotility agents if prescribed by the healthcare provider

- Maintain good personal hygiene

- If diarrhea persists for more than 10 days, should follow up with the primary provider

- Deterrence and Patient Education

- Wash hands regularly

- Avoid shellfish from waters that are contaminated

- Wash all foods before consumption

- Drink bottled water when traveling

- Avoid consumption of raw poultry or eggs

- When traveling, consume dry foods and carbonated beverages

- Avoid water and ice from the street

- Avoid drinking water from lakes and rivers

- Pearls and Other Issues

There is a strong correlation with travelers’ diarrhea and the subsequent development of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with some studies suggesting up to 50% incidence.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The key to traveler's diarrhea is preventing it. Today, nurses, the primary care provider and the pharmacists are in the prime position to educate the patient on the importance of hydration and good hygiene. The traveler should be educated on drinking bottled water and washing all fresh fruit and vegetables prior to consumption. Plus, travelers should be warned not to drink from lakes and streams. Carrying small packets of alcohol desansitizer to wash hands can be very helpful when hand washing is not possible.

The pharmacist should educate the traveler on managing the symptoms of diarrhea with over-the-counter medications or loperamide. Travelers should be discouraged from taking prophylactic antibiotics when traveling, as this leads to more harm than good. Finally, the traveler should be educated on the symptoms of dehydration and when to seek medical care. The primary care clinicians should monitor patients until there is a complete resolution of symptoms. Any patient that fails to improve within a few days should be referred to a specialist for further workup. With open communication between the team members, the morbidity of traveler's diarrhea can be reduced. [1] [8] (level V)

The prognosis for most patients with traveler's diarrhea is excellent. However, thousands of patients go to the emergency departments each year looking for a magical cure. Hydration is the key and admission is only required for severe dehydration and orthostatic hypotension. The elderly and children under the age of 4 are at the highest risk for developing complications, which often occur because of self-prescribing of over-the-counter medications. [13] [14] (Level V)

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Noel Dunn declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Chika Okafor declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Dunn N, Okafor CN. Travelers Diarrhea. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Travelers Diarrhea (Nursing). [StatPearls. 2024] Travelers Diarrhea (Nursing). Dunn N, Okafor CN, Knizel JE. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Review Travelers' Diarrhea: A Clinical Review. [Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Dru...] Review Travelers' Diarrhea: A Clinical Review. Leung AKC, Leung AAM, Wong AHC, Hon KL. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2019; 13(1):38-48.

- Review Travelers' diarrhea. [Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010] Review Travelers' diarrhea. Hill DR, Beeching NJ. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct; 23(5):481-7.

- Review [Travelers' diarrhea]. [Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013] Review [Travelers' diarrhea]. Burchard GD, Hentschke M, Weinke T, Nothdurft HD. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2013 Aug; 138(33):1673-83; quiz 1684-6. Epub 2013 Aug 2.

- Review Beyond immunization: travelers' infectious diseases. 1--Diarrhea. [J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2015] Review Beyond immunization: travelers' infectious diseases. 1--Diarrhea. El-Bahnasawy M, Morsy TA. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2015 Apr; 45(1):29-42.

Recent Activity

- Travelers Diarrhea - StatPearls Travelers Diarrhea - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

Travellers’ diarrhoea

Chinese translation.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Jessica Barrett , infectious diseases registrar 1 ,

- Mike Brown , consultant in infectious diseases and tropical medicine 1 2

- 1 Hospital for Tropical Diseases, University College London Hospitals NHS Trust, London WC1E 6AU, UK

- 2 Clinical Research Department, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK

- Correspondence to: J Barrett jessica.barrett{at}gstt.nhs.uk

What you need to know

Enterotoxic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is the most common cause of acute travellers’ diarrhoea globally

Chronic (>14 days) diarrhoea is less likely to be caused by bacterial pathogens

Prophylactic antibiotic use is only recommended for patients vulnerable to severe sequelae after a short period of diarrhoea, such as those with ileostomies or immune suppression

A short course (1-3 days) of antibiotics taken at the onset of travellers’ diarrhoea reduces the duration of the illness from 3 days to 1.5 days

Refer patients with chronic diarrhoea and associated symptoms such as weight loss for assessment by either an infectious diseases specialist or gastroenterologist

Diarrhoea is a common problem affecting between 20% and 60% of travellers, 1 particularly those visiting low and middle income countries. Travellers’ diarrhoea is defined as an increase in frequency of bowel movements to three or more loose stools per day during a trip abroad, usually to a less economically developed region. This is usually an acute, self limiting condition and is rarely life threatening. In mild cases it can affect the enjoyment of a holiday, and in severe cases it can cause dehydration and sepsis. We review the current epidemiology of travellers’ diarrhoea, evidence for different management strategies, and the investigation and treatment of persistent diarrhoea after travel.

We searched PubMed and Cochrane Library databases for “travellers’ diarrhoea,” and “travel-associated diarrhoea,” to identify relevant articles, which were added to personal reference collections and clinical experience. Where available, systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials were preferentially selected.

Who is at risk?

Variation in incidence 1 2 may reflect the degree of risk for different travel destinations and dietary habits while abroad. Destinations can be divided into low, medium, and high risk (see box 1). Rates of diarrhoea are likely to correlate closely with the quality of local sanitation.

Box 1: Risk of travellers’ diarrhoea according to destination 1 3

High risk destinations.

South and South East Asia*

Central America*

West and North Africa*

South America

East Africa

Medium risk

South Africa

North America

Western Europe

Australia and New Zealand

*Regions with particularly high risk of travellers’ diarrhoea

Backpackers have roughly double the incidence of diarrhoea compared with business travellers. 4 Travel in cruise ships is associated with large outbreaks of viral and bacterial gastroenteritis. 5 General advice is to avoid eating salads, shellfish, and uncooked meats. There is no strong evidence that specific dietary measures reduce incidence of diarrhoea, but studies examining this are likely to be biased by imperfect recall of what was eaten. 6 Risk factors for travellers’ diarrhoea are listed in box 2.

Box 2: Factors increasing risk of travellers’ diarrhoea 4 7 8 9

By increased dietary exposure.

Backpacking

Visiting friends and family

All-inclusive holidays (such as in cruise ships)

By increased susceptibility to an infectious load

Age <6 years

Use of H 2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors

Altered upper gastrointestinal anatomy

Genetic factors (blood group O predisposes to shigellosis and severe cholera infection)

What are the most important causes of travellers’ diarrhoea?

Most studies report a failure to identify the causative pathogen in between 40% and 70% of cases. 10 This includes multicentre studies based in high prevalence settings (that is, during travel). 3 10 11 12 This low diagnostic yield is partly due to delay in obtaining samples and partly due to the insensitivity of laboratory investigations. Older studies did not consistently attempt to identify enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC), and surveillance studies vary in reporting of other E coli species. 3 Where a pathogen is identified, bacteria are the commonest cause of acute travellers’ diarrhoea, with the remainder being caused by norovirus, rotavirus, or similar viruses (see table 1 ⇓ ). Protozoa such as Giardia lamblia can also cause acute diarrhoea, but they are more often associated with persistent diarrhoea, lasting more than two weeks. Cyclospora catayensis , another protozoan cause of diarrhoea, was identified in an increased number of symptomatic travellers returning from Mexico to the UK and Canada in 2015. 13

Frequency of pathogens causing travellers’ diarrhoea 2 3 10 11 12

- View inline

Table 1 ⇑ illustrates overall prevalence of causative agents in returning travellers with diarrhoea. However relative importance varies with country of exposure. Rates of enterotoxigenic E coli (ETEC) are lower in travellers returning from South East Asia than in those returning from South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America, whereas rates of Campylobacter jejuni are higher. Norovirus is a more common cause in travellers to Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, and Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica are more common in travellers to South and South East Asia. 10

The importance of enterotoxigenic E coli as a cause for diarrhoea in travellers returning from Latin America has been decreasing over the past four decades. 10 A large scale analysis of EuroTravNet surveillance data shows increasing incidence of Campylobacter jejuni infection in travellers returning from India, Thailand, and Pakistan. 2

How does travellers’ diarrhoea present?

Most episodes of travellers’ diarrhoea start during the first week of travel, with the peak incidence on the second or third day after arrival. 8 14

Typically diarrhoea caused by enterotoxigenic E coli (“turista”) is watery and profuse, and preceded by abdominal cramps, nausea, and malaise. Symptoms are not a reliable guide to aetiology, but upper gastrointestinal manifestations such as bloating and belching tend to predominate with Giardia lamblia , while colitic symptoms such as urgency, bloody diarrhoea, and cramps are seen more often with Campylobacter jejuni and Shigella spp.

Most episodes will last between one and seven days, with approximately 10% lasting for longer than one week, 5% lasting more than two weeks, and 1% lasting more than 30 days. 8 During the illness, few patients will be severely incapacitated (in one large prospective cohort about 10% of 2800 participants were confined to bed or consulted a physician), but planned activities are often cancelled or postponed. 8

How can travellers’ diarrhoea be prevented?

Several controlled trials have failed to demonstrate an impact of food and drink hygiene advice on rates of diarrhoea. 15 However, the clear food-related source of most diarrhoeal pathogens means that general consensus among travel physicians is to continue to recommend boiling water, cooking food thoroughly, and peeling fruit and vegetables. 6 Other basic advice includes avoiding ice, shellfish, and condiments on restaurant tables, using a straw to drink from bottles, and avoiding salads and buffets where food may have been unrefrigerated for several hours. Travellers should be advised to drink bottled water where available, including in alcoholic drinks, as alcohol does not sterilise non-bottled water. If bottled water is not available, water can be purified by boiling, filtering, or use of chlorine based tablets. 16 There is some weak evidence that use of alcohol hand gel may reduce diarrhoea rates in travellers, 17 but, based on studies in non-travellers, it is reasonable to strongly encourage travellers to adhere to good hand hygiene measures. Two recent systematic reviews estimated hand washing with soap reduces the risk of diarrhoeal illness by 30-40%. 18 19

When is antibiotic prophylaxis recommended?

For most travellers antibiotic chemoprophylaxis (that is, daily antibiotics for the duration of the trip) is not recommended. While diarrhoea is annoying and distressing, severe or long term consequences from a short period of diarrhoea are rare, and routine use of chemoprophylaxis would create a large tablet burden and expose users to possible adverse effects of antibiotic therapy such as candidiasis and diarrhoea associated with Clostridium difficile .

Chemoprophylaxis should be offered to those with severe immune suppression (such as from chemotherapy for malignancy or after a tissue transplant, or advanced HIV infection), underlying intestinal pathology (inflammatory bowel disease, ileostomies, short bowel syndrome), and other conditions such as sickle cell disease or diabetes where reduced oral intake may be particularly dangerous (table 2 ⇓ ). 22 These patient groups may be unable to tolerate the clinical effects and dehydration associated with even mild diarrhoea, or the consequences of more invasive complications such as bacteraemia. For such patients, it is important to discuss the benefits of treatment aimed at preventing diarrhoea and its complications against the risks of antibiotic associated diarrhoea and other side effects. If antibiotics are prescribed then consideration should be given to any possible interactions with other medications that the patient is taking.

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis options for immunosuppressed or other high risk travellers

A small comparative study in US soldiers showed that malaria prophylaxis with daily doxycycline has the added benefit of reducing rates of travellers’ diarrhoea caused by enterotoxigenic E coli and Campylobacter jejuni . 23

Do vaccines have a role in prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea?

Vaccines have been developed and licensed against Salmonella typhi , Vibrio cholerae , and rotavirus—all with reasonable efficacy. However, unlike enterotoxigenic E coli , none of these is a major cause of travellers’ diarrhoea, and only vaccines against S typhi are recommended for most travellers to endemic settings. Phase 3 trials of enterotoxigenic E coli toxin vaccines have been undertaken but have failed to demonstrate efficacy. 24 Studies suggest vaccines against enterotoxigenic E coli would have a major public health impact in high burden countries, and further candidate vaccines are in development. 25

What are the options for self administered treatment?

Table 3 ⇓ summarises the options for self treatment.

Summary of self treatment choices

Anti-motility agents and oral rehydration therapy

For most cases of travellers’ diarrhoea, oral rehydration is the mainstay of treatment. This can be achieved with clear fluids such as diluted fruit juice or soups. Young children, elderly people, and those at greater risk from dehydration (that is, those with medical comorbidities) are recommended to use oral rehydration salts (or a mixture of six level teaspoons of sugar and half a teaspoon of salt in a litre of clean water if rehydration salts are unavailable) (see http://rehydrate.org/rehydration/index.html ).

Anti-motility agents such as loperamide may be appropriate for mild symptoms, or where rapid cessation of diarrhoea is essential. Case reports of adverse outcomes such as intestinal perforation suggest anti-motility agents should be avoided in the presence of severe abdominal pain or bloody diarrhoea, which can signify invasive colitis. 26 Systematic review of several randomised controlled trials have demonstrated a small benefit from taking bismuth subsalicylate, but this has less efficacy in reducing diarrhoea frequency and severity than loperamide. 27

Antibiotics

Symptomatic treatment is usually adequate and reduces antibiotic use. However, some travellers will benefit from rapid cessation of diarrhoea, particularly if they are in a remote area with limited access to sanitation facilities or healthcare. Several systematic reviews of studies comparing antibiotics (including quinolones, azithromycin, and rifaximin) against placebo have shown consistent shortening of the duration of diarrhoea to about one and a half days from around three days. 28 29 30 Short courses (one to three days) of antibiotics are usually sufficient to effect a cure. 30

For some people travelling to high and moderate risk areas (see box 1) it will be appropriate to provide a short course of a suitable antibiotic, with advice to start treatment as soon as they develop diarrhoea and to keep well hydrated. Choice of antibiotic will depend on allergy history, comorbidities, concomitant medications, and destination. Avoid quinolones for both prophylaxis and treatment of travellers to South East and South Asia as levels of quinolone resistance are high. 31 Azithromycin remains effective in these areas, but resistance rates are likely to increase.

A meta-analysis of nine randomised trials showed that the addition of loperamide to antibiotic treatment (including azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and rifamixin) resulted in statistically significantly higher rates of cure at 24 and 48 hours compared with antibiotic alone. 32 Travellers can be advised to add loperamide to their antibiotic treatment to reduce the time to symptomatic improvement as long as there are no features of invasive colitis such as severe pain, high fever, or blood visible in the diarrhoea. 30 If any of these symptoms develop, travellers are advised to seek medical advice immediately.

Returned travellers with persistent diarrhoea

Most bacterial causes mentioned do not cause persistent diarrhoea in immune competent adults. Travellers with diarrhoea persisting beyond 14 days may present in primary or secondary care on their return and require assessment for other underlying causes of persistent diarrhoea.

Table 4 ⇓ lists the important clinical history and symptoms that can point to the underlying cause.

Assessment of chronic diarrhoea

What investigations should be sent?

For diarrhoeal symptoms that persist beyond 14 days following travel (or sooner if there are other concerning features such as fever or dysentery), offer patients blood tests for full blood count, liver and renal function, and inflammatory markers; stool samples for microscopy and culture; and examination for ova, cysts, and parasites. Historically, advice has been to send three stool samples for bacterial culture, but this is unlikely to increase the diagnostic yield. Instead, stool microscopy can be used to distinguish inflammatory from non-inflammatory causes: a small observational study found presence of faecal leucocytes was predictive of a positive bacterial stool culture. 33 Yield from stool culture may be increased by dilution of the faecal sample, and the introduction of molecular tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for common gastrointestinal pathogens such as Campylobacter spp may decrease turnaround times and increase yield. 34

Additional tests should be offered according to symptoms and risk (table 4 ⇑ ). If the patient has eosinophilia and an appropriate travel history, the possibility of schistosomiasis, strongyloides, and other helminthic infections should be considered. While schistosomiasis can rarely cause diarrhoea in the context of acute infection, serology may be negative in the first few months of the illness.

Imaging is required only if the patient has signs of severe colitis or local tenderness, in which instances toxic megacolon, inflammatory phlegmon, and hepatic collections should be excluded. Patients with severe colitis or proctitis may need joint assessment with gastroenterology and consideration of endoscopy, or laparotomy if perforation has occurred.

Where infectious and non-infectious causes have been appropriately excluded, the most likely diagnosis is post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome, although diarrhoea can also herald underlying bowel pathology and anyone with red flags for malignancy should be referred by the appropriate pathway for assessment. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome has an incidence of around 30% after an acute episode of travel associated gastroenteritis. 35 36 It is more commonly a sequela of prolonged episodes of diarrhoea or diarrhoea associated with fever and bloody stools. 36 There is weak evidence from small randomised trials suggesting that exclusion of foods high in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAP) may be helpful. 37 Exclusion of dietary lactose and use of loperamide, bile acid sequestrants, and probiotics can also be tried, but there is limited evidence for long term benefit. 35 37 38

How should giardiasis be managed?

The most common pathogen identified in returning travellers with chronic diarrhoea is Giardia lamblia, particularly among people returning from South Asia. 39 Use of G lamblia PCR testing has increased detection, 40 which potentially will identify infection in some patients previously labelled as having post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and in those whose diarrhoea may have been attributed to non-pathogenic protozoa. Most patients respond to 5-nitroimidazoles (a systematic review of a large number of trials has shown similar cure rates with tinidazole 2 g once only or metronidazole 400 mg three times daily for five days 41 ), but refractory cases are increasingly common and require investigation, identification of underlying risk factors, and repeated treatment (various antimicrobials have been shown to be effective but may have challenging risk profiles). .

Questions for future research

What is the justification for using antibiotics to treat a usually self limiting illness, in the wider context of rising levels of global antimicrobial resistance rates? What is the clinical impact of resistant enterobacteriaciae found in stool samples from returning travellers? 42 43

To what extent do host genetic factors increase susceptibility to gastrointestinal pathogens, and can this help to identify at risk populations and tailor treatments to individual patients?

What is the long term efficacy of new pharmacological treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and rifaximin in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome?

Tips for non-specialists

Include consideration of chemoprophylaxis for high risk individuals in pre-travel assessment

Advise all travellers on hygiene measures (such as hand washing and food consumption) and symptom management of diarrhoea

Avoid quinolones for prophylaxis or treatment in travellers to South East and South Asia

Where diarrhoea persists beyond 14 days, consider investigations to rule out parasitic and non-infectious causes. The presence of white blood cells on stool microscopy indicates an inflammatory cause

Additional educational resources

Resources for patients.

National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC): http://travelhealthpro.org.uk/travellers-diarrhoea/

Provides pre-travel advice, as well as links to country-specific advice

Fit for Travel: www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/advice/disease-prevention-advice/travellers-diarrhoea.aspx

Provides similar pre-travel advice on hygiene and disease prevention

Patient.co.uk: http://patient.info/doctor/travellers-diarrhoea-pro

Has patient leaflets and more detailed information about investigation and management of travellers’ diarrhoea

Resources for healthcare professionals

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention yellow book: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/the-pre-travel-consultation/travelers-diarrhea

Provides a guide to pre-travel couselling

Rehydration Project website: http://rehydrate.org/rehydration/index.html

Has additional information about non-pharmacological management of diarrhoea

How patients were involved in the creation of the article

No patients were involved in the creation of this review.

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript. MB is guarantor. We thank Dr Ron Behrens for sharing his extensive expertise on this subject.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Greenwood Z, Black J, Weld L, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Gastrointestinal infection among international travelers globally. J Travel Med 2008 ; 15 : 221 - 8 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00203.x pmid:18666921 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Schlagenhauf P, Weld L, Goorhuis A, et al. EuroTravNet. Travel-associated infection presenting in Europe (2008-12): an analysis of EuroTravNet longitudinal, surveillance data, and evaluation of the effect of the pre-travel consultation. Lancet Infect Dis 2015 ; 15 : 55 - 64 . doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71000-X pmid:25477022 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Health Protection Agency. Foreign travel-associated illness: a focus on travellers’ diarrhoea. HPA, 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140714084352/http:/www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1287146380314 .

- ↵ Schindler VM, Jaeger VK, Held L, Hatz C, Bühler S. Travel style is a major risk factor for diarrhoea in India: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015 ; 21 : 676.e1 - 4 . doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.005 pmid:25882361 . OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Freeland AL, Vaughan GH Jr, , Banerjee SN. Acute gastroenteritis on cruise ships - United States, 2008-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016 ; 65 : 1 - 5 . doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6501a1 pmid:26766396 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med 2009 ; 16 : 149 - 60 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00299.x pmid:19538575 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Bavishi C, Dupont HL. Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011 ; 34 : 1269 - 81 . doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04874.x pmid:21999643 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Pitzurra R, Steffen R, Tschopp A, Mutsch M. Diarrhoea in a large prospective cohort of European travellers to resource-limited destinations. BMC Infect Dis 2010 ; 10 : 231 . doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-231 pmid:20684768 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Flores J, Okhuysen PC. Genetics of susceptibility to infection with enteric pathogens. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009 ; 22 : 471 - 6 . doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283304eb6 pmid:19633551 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers’ diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009 ; 80 : 609 - 14 . pmid:19346386 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ von Sonnenburg F, Tornieporth N, Waiyaki P, et al. Risk and aetiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet 2000 ; 356 : 133 - 4 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02451-X pmid:10963251 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler’s diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA 1999 ; 281 : 811 - 7 . doi:10.1001/jama.281.9.811 pmid:10071002 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Nichols GL, Freedman J, Pollock KG, et al. Cyclospora infection linked to travel to Mexico, June to September 2015. Euro Surveill 2015 ; 20 . doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.43.30048 pmid:26536814 .

- ↵ Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler’s diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA. 1999 ; 281 : 811 - 7 . doi:10.1001/jama.281.9.811 pmid:10071002 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ DuPont HL. Systematic review: prevention of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008 ; 27 : 741 - 51 . doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03647.x pmid:18284650 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Clasen TF, Alexander KT, Sinclair D, et al. Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 ; 10 : CD004794 . pmid:26488938 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Henriey D, Delmont J, Gautret P. Does the use of alcohol-based hand gel sanitizer reduce travellers’ diarrhea and gastrointestinal upset?: A preliminary survey. Travel Med Infect Dis 2014 ; 12 : 494 - 8 . doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.07.002 pmid:25065273 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Ejemot-Nwadiaro RI, Ehiri JE, Arikpo D, Meremikwu MM, Critchley JA. Hand washing promotion for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 ; 9 : CD004265 . pmid:26346329 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Freeman MC, Stocks ME, Cumming O, et al. Hygiene and health: systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Trop Med Int Health 2014 ; 19 : 906 - 16 . doi:10.1111/tmi.12339 pmid:24889816 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Hu Y, Ren J, Zhan M, Li W, Dai H. Efficacy of rifaximin in prevention of travelers’ diarrhea: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Travel Med 2012 ; 19 : 352 - 6 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00650.x pmid:23379704 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- Alajbegovic S, Sanders JW, Atherly DE, Riddle MS. Effectiveness of rifaximin and fluoroquinolones in preventing travelers’ diarrhea (TD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2012 ; 1 : 39 . doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-39 pmid:22929178 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Sommet J, Missud F, Holvoet L, et al. Morbidity among child travellers with sickle-cell disease visiting tropical areas: an observational study in a French tertiary care centre. Arch Dis Child 2013 ; 98 : 533 - 6 . doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-302500 pmid:23661574 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Arthur JD, Echeverria P, Shanks GD, Karwacki J, Bodhidatta L, Brown JE. A comparative study of gastrointestinal infections in United States soldiers receiving doxycycline or mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1990 ; 43 : 608 - 13 . pmid:2267964 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Behrens RH, Cramer JP, Jelinek T, et al. Efficacy and safety of a patch vaccine containing heat-labile toxin from Escherichia coli against travellers’ diarrhoea: a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled field trial in travellers from Europe to Mexico and Guatemala. Lancet Infect Dis 2014 ; 14 : 197 - 204 . doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70297-4 pmid:24291168 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Bourgeois AL, Wierzba TF, Walker RI. Status of vaccine research and development for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Vaccine 2016 ; S0264-410X(16)00287-5 . pmid:26988259 .

- ↵ McGregor A, Brown M, Thway K, Wright SG. Fulminant amoebic colitis following loperamide use. J Travel Med 2007 ; 14 : 61 - 2 . doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00096.x pmid:17241255 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Heather CS. Travellers’ diarrhoea. Systematic review 901. BMJ Clin Evid 2015 www.clinicalevidence.com/x/systematic-review/0901/overview.html .

- ↵ De Bruyn G, Hahn S, Borwick A. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000 ;( 3 ): CD002242 . pmid:10908534 .

- ↵ Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J, Ekdahl K. A meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clin Infect Dis 2007 ; 44 : 696 - 700 . doi:10.1086/509924 pmid:17278062 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Steffen R, Hill DR, DuPont HL. Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA 2015 ; 313 : 71 - 80 . doi:10.1001/jama.2014.17006 pmid:25562268 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Dalhoff A. Global fluoroquinolone resistance epidemiology and implictions for clinical use. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2012 ; 2012 : 976273 . pmid:23097666 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in traveler’s diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2008 ; 47 : 1007 - 14 . doi:10.1086/591703 pmid:18781873 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ McGregor AC, Whitty CJ, Wright SG. Geographic, symptomatic and laboratory predictors of parasitic and bacterial causes of diarrhoea in travellers. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012 ; 106 : 549 - 53 . doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.04.008 pmid:22818743 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Public Health England. Investigations of faecal specimens for enteric pathogens. UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations. B 30 Issue 8.1. 2014. www.hpa.org.uk/SMI/pdf .

- ↵ DuPont AW. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2008 ; 46 : 594 - 9 . doi:10.1086/526774 pmid:18205536 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Schwille-Kiuntke J, Mazurak N, Enck P. Systematic review with meta-analysis: post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome after travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015 ; 41 : 1029 - 37 . doi:10.1111/apt.13199 pmid:25871571 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Halland M, Saito YA. Irritable bowel syndrome: new and emerging treatments. BMJ 2015 ; 350 : h1622 . doi:10.1136/bmj.h1622 pmid:26088265 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Orekoya O, McLaughlin J, Leitao E, Johns W, Lal S, Paine P. Quantifying bile acid malabsorption helps predict response and tailor sequestrant therapy. Clin Med (Lond) 2015 ; 15 : 252 - 7 . doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.15-3-252 pmid:26031975 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Swaminathan A, Torresi J, Schlagenhauf P, et al. GeoSentinel Network. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers. J Infect 2009 ; 59 : 19 - 27 . doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2009.05.008 pmid:19552961 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Nabarro LE, Lever RA, Armstrong M, Chiodini PL. Increased incidence of nitroimidazole-refractory giardiasis at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London: 2008-2013. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015 ; 21 : 791 - 6 . doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.04.019 pmid:25975511 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Pasupuleti V, Escobedo AA, Deshpande A, Thota P, Roman Y, Hernandez AV. Efficacy of 5-nitroimidazoles for the treatment of giardiasis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014 ; 8 : e2733 . doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002733 pmid:24625554 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Tham J, Odenholt I, Walder M, Brolund A, Ahl J, Melander E. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in patients with travellers’ diarrhoea. Scand J Infect Dis 2010 ; 42 : 275 - 80 . doi:10.3109/00365540903493715 pmid:20121649 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Kantele A. A call to restrict prescribing antibiotics for travellers’ diarrhea--Travel medicine practitioners can play an active role in preventing the spread of antimicrobial resistance. Travel Med Infect Dis 2015 ; 13 : 213 - 4 . doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.05.005 pmid:26005160 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

JOHNNIE YATES, M.D.

Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(11):2095-2100

Patient Information: Seen related handout on traveler’s diarrhea , written by the author of this article.

Acute diarrhea affects millions of persons who travel to developing countries each year. Food and water contaminated with fecal matter are the main sources of infection. Bacteria such as enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli , enteroaggregative E. coli , Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella are common causes of traveler’s diarrhea. Parasites and viruses are less common etiologies. Travel destination is the most significant risk factor for traveler’s diarrhea. The efficacy of pretravel counseling and dietary precautions in reducing the incidence of diarrhea is unproven. Empiric treatment of traveler’s diarrhea with antibiotics and loperamide is effective and often limits symptoms to one day. Rifaximin, a recently approved antibiotic, can be used for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea in regions where noninvasive E. coli is the predominant pathogen. In areas where invasive organisms such as Campylobacter and Shigella are common, fluoroquinolones remain the drug of choice. Azithromycin is recommended in areas with quinolone-resistant Campylobacter and for the treatment of children and pregnant women.

Acute diarrhea is the most common illness among travelers. Up to 55 percent of persons who travel from developed countries to developing countries are affected. 1 , 2 A study 3 of Americans visiting developing countries found that 46 percent acquired diarrhea. The classic definition of traveler’s diarrhea is three or more unformed stools in 24 hours with at least one of the following symptoms: fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, tenesmus, or bloody stools. Milder forms can present with fewer than three stools (e.g., an abrupt bout of watery diarrhea with abdominal cramps). Most cases occur within the first two weeks of travel and last about four days without treatment. 1 , 3 Although traveler’s diarrhea rarely is life threatening, it can result in significant morbidity; one in five travelers with diarrhea is bedridden for a day and more than one third have to alter their activities. 1 , 3

Destination is the most significant risk factor for developing traveler’s diarrhea. 1 – 4 Regions with the highest risk are Africa, South Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Travelers who are immunocompromised and those with lowered gastric acidity (e.g., patients taking histamineH 2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors) are more susceptible to traveler’s diarrhea. Recently, a genetic susceptibility has been demonstrated. 5 Younger age and adventurous travel increase the risk of developing traveler’s diarrhea, 3 , 6 but persons staying at luxury resorts or on cruise ships also are at risk. 7 , 8

Food and water contaminated with fecal matter are the main reservoirs for the pathogens that cause traveler’s diarrhea. Unsafe foods and beverages include salads, unpeeled fruits, raw or poorly cooked meats and seafood, unpasteurized dairy products, and tap water. Eating in restaurants increases the probability of contracting traveler’s diarrhea 6 and food from street vendors is particularly risky. 9 , 10 Cold sauces, salsas, and foods that are cooked and then reheated also are risky. 6 , 11

In contrast to the largely viral etiology of gastroenteritis in the United States, diarrhea acquired in developing countries is caused mainly by bacteria 1 , 4 , 6 , 12 ( Table 1 ) . Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is the pathogen most frequently isolated, but other types of E. coli such as enteroaggregative E. coli have been recognized as common causes of traveler’s diarrhea. 13 Invasive pathogens such as Campylobacter, Shigella, and non-typhoid Salmonella are relatively common depending on the region, while Aeromonas and non-cholera Vibrio species are encountered less frequently.

Protozoal parasites such as Giardia lamblia , Entamoeba histolytica , and Cyclospora cayetanensis are uncommon causes of traveler’s diarrhea, but increase in importance when diarrhea lasts for more than two weeks. 14 Parasites are diagnosed more frequently in returning travelers because of longer incubation periods (often one to two weeks) and because bacterial pathogens may have been treated with antibiotics. Rotavirus and noroviruses are infrequent causes of traveler’s diarrhea, although noroviruses have been responsible for outbreaks on cruise ships.

The prevalence of specific organisms varies with travel destination. 1 , 4 , 12 , 13 , 15 Available data suggest that E. coli is the predominant cause of traveler’s diarrhea in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa, while invasive pathogens are relatively uncommon. Enterotoxigenic E. coli and enteroaggregative E. coli may be responsible for up to 71 percent of cases of traveler’s diarrhea in Mexico. 13 In contrast, Campylobacter is a leading cause of traveler’s diarrhea in Thailand 15 – 17 and also is common in Nepal. 6 Regional variation also exists with parasitic causes of traveler’s diarrhea ( Table 2 ) . 12 , 13 For example, Cyclospora is endemic in Nepal, Peru, and Haiti.

Food poisoning is part of the differential diagnosis of traveler’s diarrhea. Gastroenteritis from preformed toxins (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus , Bacillus cereus ) is characterized by a short incubation period (one to six hours), and symptoms typically resolve within 24 hours. 18 Seafood ingestion syndromes such as diarrhetic shellfish poisoning, ciguatera poisoning, and scombroid poisoning also can cause diarrhea in travelers. These syndromes can be distinguished from traveler’s diarrhea by symptoms such as perioral numbness and reversal of temperature sensation (ciguatera poisoning) or flushing and warmth (scombroid poisoning). 19

Although travelers often are advised to “Boil it, cook it, peel it, or forget it,” data on the effectiveness of dietary precautions in preventing traveler’s diarrhea are inconclusive. 3 , 6 , 20 Many travelers find it difficult to adhere to dietary recommendations. 21 In a study 3 of American travelers, nearly one half developed diarrhea despite pretravel advice on avoidance measures; even persons who strictly followed dietary recommendations developed diarrhea. Avoiding high-risk foods and adventuresome eating behaviors may reduce the inoculum of ingested pathogens or prevent the development of other enteric diseases such as typhoid and hepatitis A and E.

Boiling is the best way to purify water. Iodination or chlorination is acceptable but does not kill Cryptosporidium or Cyclospora, and increased contact time is required to kill Giardia in cold or turbid water. 22 Filters with iodine resins generally are effective in purifying water, although it is uncertain whether the contact time with the resin is sufficient to kill viruses. Bottled water generally is safe if the cap and seal are intact.

DRUG PROPHYLAXIS

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) even for high-risk travelers because it can lead to drug-resistant organisms and may give travelers a false sense of security. Although antibiotic prophylaxis does not prevent viral or parasitic infection, some health care professionals believe that it may be an option for travelers who are at high risk of developing traveler’s diarrhea and related complications (e.g., immunocompromised persons). Prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones is up to 90 percent effective. 23 Rifaximin (Xifaxan) may prove to be the preferred antibiotic because it is not absorbed and is well tolerated, although data on its effectiveness for prophylaxis have not yet been published.

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) provides a rate of protection of about 60 percent against traveler’s diarrhea. 24 However, it is not recommended for persons taking anticoagulants or other salicylates. Because bismuth subsalicylate interferes with the absorption of doxycycline (Vibramycin), it should not be taken by travelers using doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis. Travelers should be warned about possible reversible side effects of bismuth subsalicylate, such as a black tongue, dark stools, and tinnitus.